In a Western historical context, human rights developed as a protective concept to defend the autonomy of individual citizens against threats coming particularly from sovereigns (states) that would try to over-extend their power into the realm of the private citizen. In the cultural context of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, however, the human rights idea is of a much more emancipatory character. There, it constitutes a struggle for truly universal human dignity through realised rights of the have-nots. Furthermore, while human rights are highly action-oriented in general, this applies particularly to the situation in developing countries. “Human rights have often been functioning as the rights of the privileged both at the world level and also in national and local societies. But the dispossessed, the underprivileged, and that is the majority of the world, they regard human rights as instruments of liberation and emancipation” (Leary 1990: 30). In such a context, human rights are used as a transformative legal resource as well as a political instrument for social change while playing their part particularly in the struggles of social movements. Obviously, it is culture that plays a primary role in this respect.

From a human rights perspective, culture acts as both a resource and a constraint. On the one hand, the cultural filter through which people experience the outside world is an indispensable resource for sustaining the globally proclaimed faith in universal dignity and equal rights. On the other, it may double as a serious constraint to that faith. Let us now examine the former aspect of culture, with special focus on the role of religion.

Why Human Rights Need Faith

The issue here is whether human rights might be regarded as self-driven and sustained in the sense of a connected worldview in which the belief in universal human dignity is grounded. In this regard, a distinction may be made between religion and faith. The term religion stems from the Latin religio in the sense of a bond. While religion may manifest itself as doctrine, rules and hierarchies, faith refers to authentic conviction and concrete commitment. It is the Muslim scholar Abdullahi An-Na’im in particular who has suggested shifting the debate on “religion and human rights” from textual interpretations of prescriptions and proscriptions to the actual understanding and practice of belief (2004). In this respect, two distinct meanings of faith may be discerned. First, there is ‘faith’ as proclaimed in the foundational human rights documents such as the Preamble to the United Nations Charter of 1945 in which the “Peoples of the United Nations … reaffirm faith in fundamental rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small” (emphasis added). This global faith may be written with a small f, whereas ‘Faith’ (with capital F) signifies a transcendental belief to drive, sustain, and inspire that faith in human dignity and its associated values of liberty, equality, and solidarity, which were proclaimed in Article 1 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

While with the United Nations Charter of 1945 the universality of human rights was firmly grounded in international law – and a great deal of political consensus on the human rights idea exists – there are still serious difficulties in realising these rights. Obviously, their inclusion in legal texts is in itself insufficient (ironically, it is often precisely in states with the most serious human rights violations that we find the most elaborate and high-sounding constitutional clauses on fundamental freedoms and entitlements). What really matters is accessible procedures of a supra‑national nature. These have been effectively created only in Europe: But in order to bring a case before the European Court of Justice, all national remedies must have been first exhausted. Hence, contentious action, however important as a remedy for human rights violations, has to be accompanied by socio‑cultural and political action aiming at cultural receptivity (De Gaay Fortman 1995).

Yet, in the period following the adoption of the UDHR, the human rights project was interpreted as a juridical challenge to legislate and to create procedural provisions for judgment of individual and state complaints. On the basis of an intrinsically neutral attitude towards the culture, regime, religious beliefs, and the level of prosperity in the country concerned, human rights violations, it had been concluded, would have to be denounced everywhere.

Naturally, the acceptance of that responsibility for protection of the human dignity of everyone requires more than just a legal basis, no matter what sorts of legal mechanisms for its realization may have been created. Indeed, the ratification of treaties, the establishment of international courts of human rights – access to which, and hence compliance, is entirely voluntary for states to enter into – and the development of human rights jurisprudence are not enough. The moral grounds for a conviction upon which responsible behaviour rests have to be constantly nurtured on the basis of a worldview shared by those concerned. Notably, insofar as the notion of human rights is to be sustained in individualism, it is ‘responsible’ individualism that matters. This is evidently not the same as ‘possessive’ individualism. Yet, the former may easily degenerate into the latter.

It is exactly those cultures in which possessive individualism has strong roots – and that includes the global village as such – which experience great difficulty with economic and social rights, as early as the stage of standard-setting. While individualism may offer a sufficient moral foundation for respecting everyone’s fundamental freedoms, it is inadequate as a basis for accepting other people’s needs as grounds for justified claims. Economic, social, and cultural rights presuppose not just free individuals but a community that accepts responsibility for the fulfilment of everyone’s basic needs.

Thus, the liberal democratic idea – according to Francis Fukuyama, the end of the history of ideas (Fukuyama, 1992) – fails here. In the ideal type of a pure free market economy, the weak find no structural protection against unemployment, disease, disability, and old age. For good reasons, dependence on the charity of the strong was considered unsatisfactory. In many industrialised countries, measures such as workers’ protection, compulsory education, professional training, and health protection constituted a structural attempt towards the realisation of economic and social rights. The social struggle that led to such achievements was nurtured by Faith in the sense of a set of ideas transcending individual existence. In this sense socialism may also be regarded as Faith.

Friedrich Hayek, the godfather of neo-liberalism, once wrote a book under the title The Mirage of Social Justice (1976). It is only a negative notion of freedom, he feels (keep your hands off other people’s property, allow everyone her liberty), that can be more than a mirage. Hence, for a vision on social justice we have to look elsewhere.

John Rawls is well known as a philosopher who has attempted to construct political principles of justice applicable to any society that tackles not just the problem of freedom, but the problem of inequalities among people as well (Rawls 1972). His ‘non-normative’ theory is based on a hypothetical social contract between citizens who, behind a veil of ignorance regarding their relative success or failure in acquiring entitlement positions, decide what is socially fair. This is not the place to review that theory critically, but it is noteworthy that Rawls’s rational-liberal theory of justice within the state did not provide a sufficient basis for him when he tried to construct a political Law of Peoples that would legitimate human rights in the international arena (Rawls 1999). For one thing, he felt compelled to abandon the three egalitarian features of his theory of justice: the fair value of political liberties, fair equality of opportunity and the difference principle. Consequently, his human rights concept deals with civil rights only, while excluding political and socio-economic rights, let alone the rights of collectivities. Moreover, his argument implies that even representatives of hierarchical societies, committed in a rather absolute sense to certain ideologies and religions and placed behind a veil of ignorance (the basic assumption in hypothetical contract theory) would accept the same law of peoples, including basic civil rights, possessed by democratic societies. But why would they? As Stanley Hoffmann reasoned:

Are societies whose governments are dogmatically committed to ideology or religion likely to respect basic human rights at all? Since there are no free elections, how would we know that their “system of law” meets “the essentials of legitimacy in the eyes of [their] own people”? Whatever the answer, what is clear is that Rawls’s law of peoples has been shaped so as to appeal to a purely hypothetical group of peoples. (1995:54)

The fallacy lies in the parallel Rawls seems to draw between an “overlapping consensus” of comprehensive doctrines that endorse a single conception of justice within a democratic political culture, and an “overlapping consensus” of societies based on very different political conceptions of justice. Such different societies could endorse only a very weak “law of peoples.” (Hoffmann 1995: 54).

Hence, for a stronger law of peoples we have to look beyond the non-ideal theory of Rawls. Indeed, one cannot escape the search for conceptual roots of human rights within the various religions themselves. Research done by Wronka would point to a preliminary conclusion that the idea of one person’s responsibility for satisfaction of another person’s needs is common to all world religions (Wronka: 1992). An example is the Bible, in which tsedâqâh implies acknowledgement of the claims of the poor, purely on basis of their need. Thus, the connection with religion may provide the necessary cultural basis for the struggle for economic, social, and cultural rights. Notably, apart from all sorts of political and economic constraints to the implementation of human rights, there also exists a major obstacle in the cultural resistance to norms and values implying that people are responsible for the well being of their fellow human beings. A ‘culture of contentment’ predominates in the post-Cold War era, paralysing the global ‘haves.’ In this connection, Christopher Lasch spoke of a rebellion of the elites and the betrayal of democracy (Lasch: 1994 (posthumous). With so many people excluded from a decent existence, the human rights project suffers from structural – day-to-day – violation; this is the core of its deficit.

In terms of human rights realisation, the true issue is of a moral cultural nature: How do people see each other? One way of seeing people in daily hardship, living in distant countries (or in any other socially or spatially constructed category), is as a threat. De Swaan, for one, has expressed the hope that the problems of ecological destruction and migration in particular might convince the world’s rich of the need for a global care system for the benefit of the poor (De Swaan 1988). Yet, reality has not validated that expectation.

A second way of viewing the deprived is as victims to whose welfare massive relief operations might be directed within the framework of modern charity. But it appears to be equally doubtful, however, that either or both these ways of seeing other people could provide sufficient inspiration and motivation for global collective action for social justice. There is a third way of viewing them, however: As fellow human beings, i.e., as people with the same dignity and fundamental rights. A crucial question arises here: What is the basis of humankind’s belief in liberty, responsibility, equality and the value of human life per se? The response to that query cannot be universal as not all men and women share the same basic convictions.

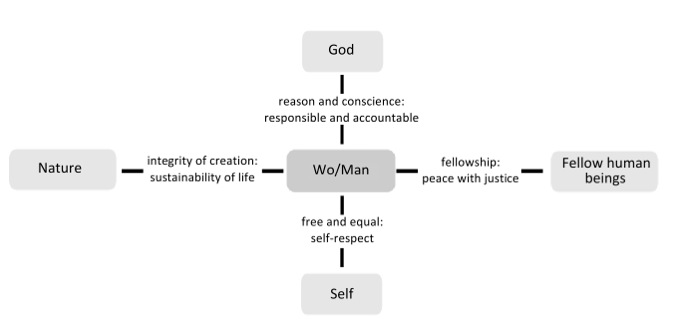

For the three Abrahamic religions – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam – Faith means trust in one God, creator of heaven and earth. The Creator is respected as the One who endowed the human being with reason and conscience, and hence continues calling people to do justice, establish peace, and respect life in the whole creation. This may be graphically represented as follows:

This Faith-based anthropology is reflected in Article 1 of UDHR, albeit with two major exceptions: There is mention of neither God nor nature. As to the first, the universality of the UDHR requires faith-based identification with its principles and values from the perspective of plural religious constituencies, including those who see the source of reason and conscience not in God but in humanity itself. Hence, the founding fathers of the UDHR (with the founding mother Eleanor Roosevelt in the forefront) refrained from any deeper grounding of that faith in the dignity and worth of the human person, which the preamble reaffirms. The second absence has to do with the times: World War II had shown the extent to which human beings could violate human dignity.

Although, as noted already, Faith-based approaches to human rights cannot be of a universal character, these distinct perspectives do not necessarily affect the universal nature of human rights as such. At the same time, such linking to the sources of that proclaimed faith in the equal dignity and worth of wo/men and their inherent freedoms and responsibilities may well play a vital part in establishing a genuine global human rights constituency. A striking illustration of a faith-based endorsement of human rights as in essence God-given came from the Roman Catholic bishops in Latin America. Notably, in his encyclical Quanta Cura with its annexed Syllabus of errors, Pope Pius IX had censured the idea of inalienable human rights as a heresy (1864). Yet, although that denunciation was never formally withdrawn, in 1992 the Latin American bishops fully endorsed the human rights idea as follows:

The equality of all human beings, created as they are in the image of God, is guaranteed and completed in Christ. From the time of his incarnation, when the Word assumes our nature and especially through his redemption on the cross, He demonstrates the value of every single human being. Therefore Christ, God and man, constitutes also the deepest source and guarantee for the dignity of the human person. Each violation of human rights is contrary to God’s plan and sinful. (CELAM 1993: 164)

In this statement, the Christian Faith is seen as the deepest foundation of all human rights. It illustrates how Faith-based approaches to human rights may even lead to a complete synthesis of two missions that are separate in origin and principle. In order to secure actual protection of human dignity, connections between secular settings of human rights and Faith-based views on their grounds are, indeed, crucial. The belief in human equality, for example, is sustained by Faith-based assumptions that all human beings spring from the same origin. An Islamic source for the belief in equality and the need for fellowship can be found in the Quran’s surah (chapter) 49, verse 13: “O mankind! We created you from a single (pair) of a male and a female …!”

Faith, then, requires (re)confirmation or (re)affirmation first as it is called in the preambles of both the UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. These documents, in other words, represent not only a conviction but also a commitment: Walk the talk! The realisation of freedom and equality in “dignity and rights” requires individual self-respect, structural incorporation of respect for each and every human being in the institutions of society, and actual day-to-day protection against abuse of power over others. Indeed, right after their Faith-based affirmation of human rights, the Latin American bishops expressed a deep concern about daily abuse. These rights, they noted, are however grossly and systematically violated from day to day

not only by terrorism, repression and attacks … but also through the existence of extreme poverty and unjust economic structures which result in extreme inequality. Political intolerance and indifference in regard to the situation of general impoverishment reveal a general contempt for concrete human life on which we cannot remain silent. (CELAM 1993: 165)

Hence, as a “pastoral action line,” the bishops request the realisation of human rights in an effective and courageous manner

based on both the gospel and the social doctrine of the Church, by word, action and cooperation, and in that way to commit ourselves to the defence of the individual and social rights of human beings, peoples, cultures and marginalised sectors of society, together with persons in a state of extreme vulnerability and prisoners. (CELAM 1993: 165)

Unquestionably then, the fellowship that human beings are called upon to establish is not just a matter of envisioning the others as free and equal creatures but also of doing justice and living together in peace. Indeed, the essence of the whole international human rights venture might be much more tuned to realisation rather than just to the intricacies of setting standards, making reservations, declaring new rights, and interpreting specific articles.

Secondly, Faith implies accountability. “Reason and conscience” – as proclaimed in article 1 of the Universal Declaration – call for a self-image based on responsibility along with accountability towards all those affected by public as well as private decision-making. As a matter of Faith, and hence of transcendental inference, human beings are accountable. Consequently, power becomes authority, based on principles and standards to protect life in dignity. Notably then, protection of all those over whom power is exercised – a core idea in the international venture for the realisation of human rights – is a Faith-based requirement.

Indeed, in a moral political sense, the principal question in respect of those living in daily hardship is not What problems will these people cause? or What can we do for these poor devils? but rather; How can their rights be realised? The way in which such questions are put is related to socio-political concepts of freedom. Does freedom mean easy access to modern entertainment? Does it mean earning a high income so that one can have a wide choice of goods while opting for many things at the same time? Does freedom imply not making choices that exclude other options – indeed, never committing oneself? Or does freedom mean choosing a particular path and staying loyal to that choice in the sense of a real commitment? For the latter, a conviction is required that directs people’s attention to more than the mere satisfaction of their own wants. Human rights, in other words, primarily imply a conviction and a commitment that is rooted in local realities, which continuously sustain and nurture that engagement through spiritual beliefs and practices transcending pure egotism and power-based instincts.

Why Religion Needs Human Rights

Religion embodies institutionalised connections with transcendental bases for morally justified behaviour. From a reality beyond direct human experience, moral standards are set with ‘eternal’ pretence. Does this mean that respect for truly universal human dignity is inherent in all religion? Practice shows it does not. First, the religious message itself may contain discriminatory elements. This applies particularly to situations in which, apart from the religious core of the message, its cultural setting is also authorised and made absolute. Religion may then sanctify a whole people or caste and hence come into conflict with the principle of human equality. The enactment of apostasy as a serious crime is a clear indication of a general attitude of considering a particular religion as being above human rights (Van Krieken 1993). Generally, such a belief is based on tradition and on interpretations of Holy Scriptures, which are not indisputable (Mirmoosavi 2010).

In the human rights mission, religion has played its part right from the start in two ways. First, freedom of worship (or non worship) is one of the fundamental human freedoms. Strikingly, realisation of this freedom is particularly problematic in a multi-religious context as absolutism easily permeates organised Faith. Secondly, religion, with all that belongs to it, i.e. beliefs as well as institutions, also falls under the universal norms of the UDHR. People determined to discriminate or even kill others for religious reasons, collide with human rights. Stunningly, the assassin of the Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, for one, told the police that he had been acting on “orders from God.”[1] Indeed, resistance to fundamental rights that obtain for everyone, such as the right to life, may be based on religious convictions too. These are usually grounded in ‘verbalism’ (a normative doctrine or method according to which judicial interpretation of authoritative texts should aim at establishing the original meaning of the text without any regard to its context (De Gaay Fortman et al 2010: 11).

Indeed, fossilisation of a certain cultural context from the past runs the inherent risk of incompatibility with current human rights standards. Moreover, contemporary religion may be subject to socio-political manipulation. For instance, right after the Rwandan genocide, Justin Hakizimana, an elder in the Presbyterian Church, observed that the church and the government had become too close:

The church went hand in hand with the politics of Habyarimana. We did not condemn what was going on because we were corrupted. None of our churches, especially the Catholics, has condemned the massacres. That is why all the church leaders have fled, because they believe they may be in trouble with their own people. (McCullum, 1995: 73)

The corruption of religious institutions here described is a gradual process that may strongly embarrass people retrospectively. This was strikingly expressed in the reaction of Reverend Mugamera, who lost his whole family (his wife and six children) in the Rwandan bloodshed:

Why did the message of the gospel fail to reach the people who were baptised? What did we lose? We lost our lives. We lost our credibility. We are ashamed. We are weak. But, most of all, we lost our prophetic mission. We could not go to the President and tell him the truth because we became sycophants to the authorities.

We have had killings here since 1959. No one condemned them. During the First Republic, they killed slowly, slowly, but no one from the churches spoke out. No one spoke on behalf of those killed. During the Second Republic, there were more killings and more people were tortured and raped and disappeared; and we did not speak out because we were comfortable.

Now there has to be a new start, a new way. We must accept that Jesus’ mission to us to preach the gospel means that we must be ready to protect the sheep, the flock – even if it means we must risk our lives for our sisters and brothers. The Bible does not know Hutu and Tutsi; neither should we. (McCullum 1995: 75)

Who would deny a crucial role for human rights in such a new start after genocide? Indeed, religion per se appeared to be insufficiently equipped to deal with the politically inspired processes of exclusion (us, not them!), thinking of others as enemies, demonization and finally extermination.

Mutually Exclusive or Supportive?

In fact, justifications for continuing violations of human rights in the name of religion tend to come from alliances of politicians with radical exclusivist religious leaders as opposed to moderate religious establishments – be it Jewish, Christian, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist or whatever religion. Religion is, indeed, subject to strong political manipulation. The strategic question is how to avoid clashes between religion and human rights effectively. Notably, generalised statements on the superiority of human rights to religion may turn out to be counterproductive, as UN special rapporteur Gáspár Bíró experienced in Sudan. His remark on the subservience of Islamic Shar’ia law to human rights in conformity with the “lex posterior” principle (posterior legislation derogates from prior laws) provided the Sudanese government with an excellent opportunity to switch from a defensive to an offensive position, denouncing his observations as blasphemous. Actually, that whole incident is just one of numerous illustrations of the tremendous challenges of rooting the global human rights mission in distinct local realities.

One conclusion, then, refers to religion as being subject to both ideologisation and institutionalisation. No matter how well rooted in people’s lifeworlds, religion needs human rights as a global justice discourse that puts the human being above ideology and the dignity of the individual person above the organisation. Indeed, the Pope’s question to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, as formulated in an exemplary story, “Mr. Gorbachev, this glasnost of yours, as I understand it (hopefully correctly), is an idea for just outside the church?” has to be answered in the negative. Religion needs human rights – including the fundamental freedom to critique power.

Reciprocally, human rights needs a firm rooting in people’s transcendental beliefs. Illustratively, after the Rwandan genocide of April 1994, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights attached an immediate priority to Rwanda. Training programmes for human rights monitors were set up all over the country. Would such a response lead to better protection against ethnicism, structural discrimination, and genocide than the teaching of the churches had apparently failed to offer? A sceptical undertone is already detectable in the question itself. The global human rights project possesses its own institutions: inter-governmental and non-governmental centres, complaints procedures with commissions, committees and courts of law, training programmes and academic teaching courses. Human rights are already seen as a “global religion” (Korzec: 1993) and that is meant in an institutional sense as well. It is precisely as such a new religion—which, implicitly, one would be free to either adopt or reject—that human rights loses its appeal as a truly global justice venture.

The real challenge remains, however, to get the global faith in a dignified and well-protected existence for everyone, rooted in all hearts and minds. Yet, as people do not usually learn human rights out of books, this tends to entail periods of sharp confrontation with the powers that be, as the recent Arab Spring has markedly illustrated. Whether religion’s supportive role in respect of that human rights struggle will continue unchanged in the post-revolutionary period, remains an open question. It is, indeed, the context that tends to determine whether religion and human rights manifest themselves as mutually exclusive or supportive. Inescapably, in other words, the nature of that relationship remains dialectical.

Bas de Gaay Fortman is the Emeritus Chair in Political Economy of the International Institute of Social Studies at Erasmus University, Rotterdam, and Professor of Political Economy of Human Rights at the Utrecht University Law School, the Netherlands. His latest book Political Economy of Human Rights: Rights, Realities and Realization was published by Routledge in May 2011.

[1]. For further information, see http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/james_haught/rabin.html

Bibiography

An-Na’im, A.A. 2004, ‘The Best of Times, and the Worst of Times: Human Agency and Human Rights in Islamic Societies’, Muslim World Journal of Human Rights Vol. 1, no. 1.

CELAM (Episcopal Conference of Latin America), 1993, Nueva Evangelización, Promoción Humana, Cultura Cristiana, “Jesucristo Ayer, Hoy y Siempre, IV conferencia General del Episcopado Latinoamericano, Santo Domingo, Republica Dominicana, 12–28 Octubre 1992, Santo Domingo: Ediciones MSC.

De Gaay, Fortman, B. 1995, ‘Human Rights, Entitlement Systems and the Problem of Cultural Receptivity’, in A. An-Na’im, J.D. Groot, H. Jansen, and H.M. Vroom, Human Rights and Religious values: an Uneasy Relationship, Grand Rapids, Eerdmans.

De Gaay Fortman, B., K. Martens & M.A. Mohamed Salih 2010, Between Text and Context: Hermeneutics, Scriptural Politics and Human Rights, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

De Swaan, A. 1988, In Care of the State: Health Care. Education and Welfare in Europe and the USA in the Modern Era, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Fukuyama, F. 1992, The End of History and the Last Man, London and New York: Penguin Books.

Hoffmann, S. 1995, “Dreams of a Just World”, The New York Review of Books, 2 November, 54–57.

McCullum, H. 1995, The Angels Have Left Us: The Rwanda Tragedy and the Churches. Geneva: WCC Publications.

Lasch, C. 1994, The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy, New York: W.W. Norton.

Leary, V.A. 1990, The Effect of Western Perspectives on International Human Rights, in A.A. An-Na’im and F.M. Deng (eds), Human Rights in Africa; Cross-Cultural Perspectives, Washington D.C.: The Brookings Institution.

McCullum, H. 1995, The Angels Have Left Us: The Rwanda Tragedy and the Churches. Geneva: WCC Publications.

Mirmoosavi, A. 2010, The Quran and Religious Freedom. The Issue of Apostasy’, in B. de Gaay Fortman, K. Martens and M.A. Mohamed Salih, Between Text and Context: Hermeneutics, Scriptural Politics and Human Rights, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rawls, J. 1972, A Theory of Justice, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rawls, J. 1999, The Law of Peoples. With ‘The Idea of Public Reason’ Revisited, Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard University Press.

Wronka, J. 1998, Human Rights and Social Policy in the 21st Century, Lanham (MD): University Press of America.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Impacts and Restrictions to Human Rights During COVID-19

- Business and Human Rights, Poverty and Power: Bridging the Political Economy Gap

- Troubling International Human Rights Advocacy

- Opinion – Human Rights: The Underlying Battlefield of the Wolf Warriors

- Exposing the Universality of Human Rights as a False Premise

- Secularism: A Religion of the 21st Century