It is clear that Africa is an emerging strategic partner of China and Beijing is investing heavily in both commercial and political terms in the continent. This has some important implications for the United States, which has long seen a number of countries in Africa as important to its broader foreign policy, has extensive trade links with the continent and is increasingly viewing Africa’s minerals of strategic interest. As a result, some over-excited analysts talk of a major competition between China and the United States in Africa – even the potential for future conflict between the two over (or in) the continent.

However, when examining Sino-African ties in the context of the United States, that hyperbole about China’s role needs to be tamed. This article seeks to analyse the contemporary nature of Sino-African relations and how the dynamics of Sino-American rivalry—or at least competition—plays out within a framework of relations and networks. In doing so, it contextualises the issues facing both Beijing and Washington, particularly in West Africa and also analyses some of the problems Chinese actors have experienced in Africa. As will be shown, Washington DC does not seem overly concerned by China’s rise in the continent; the United States’ economic and political ties with Africa are robust and not threatened by Chinese interests.

The West African Context

In today’s globalized world economy, oil provides the foundation for commerce and industry, the means for transportation, and provides the ability to wage war. It is, the prize to capture.[1] In this context, in recent times, there has been growing international interest in West Africa. So much so, that there is now talk of a “scramble for Africa’s oil,” redolent of the nineteenth century’s Scramble for Africa.[2] West Africa has now emerged as a hugely important source of oil in the global economy and this is necessarily impacting upon the region’s relations with both China and the United States. This situation is largely due to new discoveries in the continent and specifically in the Gulf of Guinea—in the years between 2005 and 2010, 20% of the world’s new production capacity is expected to come from Africa’ and the instability of oil markets in the Middle East, which compels the search for alternative supply locations.[3]

Whilst analyses indicate that the entire African continent holds only about ten percent of the world’s total oil reserves,[4] by 2015 the United States is predicted to source twenty-five percent of its oil imports from Africa.[5] In fact, according to the US Department of Energy, the combined oil output by all African producers is projected to rise by 91 per cent between 2002 and 2025 (from 8.6 to 16.4 million barrels per day).[6] Thus within oil circles, there is growing excitement about the ‘alluring global source of energy in Africa’.[7] Indeed, as the only region in which oil production is actually rising, Africa has been identified as the “final frontier” in the quest for global oil supplies.[8]

The burgeoning oil fields in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in the Gulf of Guinea, have become of major geo-strategic importance to the oil-dependent industrialised economies. In fact, it might now be stated that the United States does not just buy oil from Africa, ‘in many ways it is dependent on African oil’ (emphasis added).[9] As Walter Kansteiner, the Assistant Secretary of State for Africa noted, ‘African oil is critical to us, and it will increase and become more important as we go forward’.[10] Thus today, African oil has become a ‘matter of US national strategic interest’,[11] granting the Gulf of Guinea ‘major strategic relevance in global energy politics’.[12] To the American Ambassador to Chad’s surprise, ‘for the first time, the two concepts—“Africa” and “US national security”—have been used in the same sentences in Pentagon documents’.[13]

Concomitantly, Africa has now emerged as a major site for competition between various oil corporations from diverse nations. Within the next few years, perhaps the largest investment in the continent’s history will be seen as billions of dollars are poured into exploration and oil production in Africa. For instance, three of the world’s largest oil corporations (Shell, Total and Chevron) are targeting 15%, 30% and 35% respectively of their global exploration and production budgets on Africa.[14] Meanwhile, it is estimated that Sub-Saharan economies will gather over $200 billion in oil revenue receipts over the next decade.[15]

Whilst it is not solely a race between Chinese and American corporations, the current dynamics in West Africa are heavily influenced by the roles and activities of actors from these two states.[16] Policymakers in both nations have identified African oil as vital to their respective nations’ national interest, albeit for different motives. It is apparent that policy analysts in Beijing see the broader global political milieu as being intrinsically linked to Chinese energy security and feel that in the current environment China is vulnerable until and unless it can diversify its oil sourcing and secure greater access to the world’s oil supplies.[17] Between 2002 and 2025 it is estimated that Chinese energy consumption will rise by 153 % and China is now the second largest consumer of oil globally, after the US, using 7 million barrels of oil a day, expected to rise to 9 million by 2011.[18] In order to fuel such a growing demand, Chinese oil corporations have entered into the competition for African oil.

From the American perspective, the ‘war on terrorism and preparations for war against Iraq…enormously increased the strategic value of West African oil reserves’.[19] The high level of interest from such major importers has certainly raised the level of competition over Africa’s oil. Whilst corporations headquartered in other states—Britain, Brazil, France, India and Malaysia, for example—are playing important roles in the ongoing Scramble and equally striving to build up their oil portfolios in Africa, it is the ostensible Sino-American competition for oil on the continent that has grabbed the most headlines: ‘There is also little doubt that the interest in Africa’soil and gas resources has spurned a rivalry between internationalactors in Africa, notably the American and Chinese governments’.[20]

However, unlike the colonial scramble for Africa, African agency is far more present in the contemporary rush for oil and this has important implications for the nature of the relationships unfolding. Many African governments are quite proactive in their roles within today’s context. Whilst the nineteenth century scramble ‘was driven and dictated by European colonial interests,’ currently, ‘African leaders act in the role of decision-makers’.[21] Whilst it is true that many African states are rich in oil, but lack sufficient capital to exploit these resources and thus create formative conditions whereby African elites might be seen as dependent upon external actors to facilitate exploitation,[22] the ability of the government to negotiate favourable contracts should not be discounted. In fact, many oil-rich African governments are quite skilful in playing the oil game—albeit for the benefit of the incumbent elites, rather than the broad masses.

Sino-American Competition?

It would be tempting to cast Chinese entry into Africa as stimulating a major competition with established Western powers in the continent. However, that does not seem to be the case—although many African actors would probably like this to exist. Certainly, some African officials believe that competition between China and the United States would have positive consequences for them. For instance, in a meeting with American officials in Beijing, the Kenyan Ambassador to China asserted that he was ‘worried that Africa would lose the benefit of having some leverage to negotiate with their donors if their development partners joined forces.’[23]

In fact, Chinese actors have often succeeded because Western companies either have not been interested in bidding for a particular project, or have not played ball with African government demands, whilst the Chinese have been prepared to do so. For example, in discussions with the American embassy in Abuja, Nigeria National Petroleum Company (NNPC) officials discussed Chinese oil companies’ attempts to obtain deep water oil mining leases and opined that ‘Shell Nigeria had opened the door for the Chinese by resisting [Abuja’s] efforts to pass the proposed Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB) and telling the National Assembly that the “Nigerian oil industry would be dead” if the PIB passed.[24] “So they brought in the Chinese.”’[25] The Chinese oil companies were not the favoured partners—far from it. In fact, the Nigerian official stated that ‘We know what had happened in the Sudan and Chad and we know enough about them to know where we want them and where we don’t.’[26] Yet the Chinese were brought in nonetheless.

The American Assistant Secretary for African Affairs, Johnnie Carson, appeared relaxed about China’s entry into Nigeria specifically when briefing American diplomats in Lagos. According to Carson, ‘The United States does not consider China a military, security or intelligence threat,’ although ‘China is a very aggressive and pernicious economic competitor with no morals.’[27] In fact, Carson asserted that Washington would only start worrying if Beijing crosses some ‘trip wires,’ listed as China developing a blue water navy, signing military base agreements, training armies, or developing intelligence operations. Carson’s tone indicated that the administration did not believe Beijing had done any of these—or sufficiently proficient enough to cause concern.[28]

Rather than being panicked by China’s rise, Carson in fact asserted that ‘The influence of the United States has increased in Africa…The United States’ reputation is stable and its popularity is the highest in Africa compared to anywhere else in the world. Obama has helped to increase that influence.’ [29] Having said that, domestic American politics has meant that the Obama Administration has engaged in a certain pushback vis-à-vis Beijing, primarily as a means to satisfy his Democrat supporters, who are suspicious of China’s impact on American jobs, and to assuage Congress. Whilst it is certainly true that a proportion of the Republican-controlled House of Representatives Congress are broadly pro-trade with China, many are suspicious of the “China threat” and see the rise of China as a globally aggressive expansion by a rival power. Pushing back against China, particularly on the issues that excite many Republicans, such as the military balance, is one way Obama can demonstrate his credentials. An example of this was the January 2011 visit by Defense Secretary Robert Gates, who publicly spoke against the Chinese military budget.

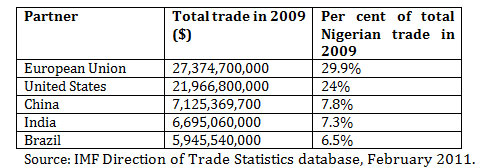

In fact, Chinese economic and political influence in Africa has been overstated by many. Regarding Nigeria, for example, China’s ties with Abuja early on in the 2000s generated a great deal of excitement within Nigeria, encouraged by Beijing’s willingness to work closely with the Obasanjo regime. This situation has now changed. In fact, trade figures show China to be a relatively small player in Nigeria’s economy and is certainly not displacing either the United States or Abuja’s traditional trading partners:

Nigeria’s Major Trade Partners, 2009

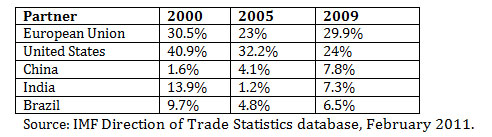

Whilst it is true that China’s share of Nigeria’s total trade is steadily going up, this is from a (very) low base and sits alongside the other “emerging powers” increased economic engagement with Abuja, as well the still predominant position within Nigeria’s economy of both the United States and the European Union:

Nigeria’s Major Trade Partners by Percentage of Total Nigerian Trade, 2000-2009

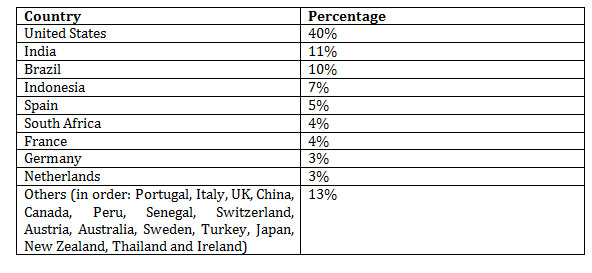

A look at the figures for oil specifically makes this point even more graphic. In 2009, Nigeria exported most of its 2.2 million bbl/d of total oil production (circa 1.9 million bbl/d were exported). Of this, close to 800,000 bbl/d (around 40 per cent) was exported to the United States. This made Nigeria the fifth largest foreign oil supplier to Washington DC. Although the volatility in Nigerian oil supplies has led to some American refiners stopping their purchases of Nigerian crude for more reliable partners, it is clear that Nigerian crude oil remains important for the United States. In contrast, China barely figures:

Nigerian oil exports by country (percentages of total Nigerian oil exports) in 2009[30]

Conclusion

The main challenge for both China and the United States is negotiating and confronting the reality of Africa’s political economy. This is something that no amount of high-sounding rhetoric from Beijing about fraternal ties and mutual benefits can hide or escape. Politics in many African countries has long been an open scramble for power in which elites compete for control of the state in order to capture the mega benefits associated with the country’s enormous oil revenues. This is the environment in which “new” actors like China must navigate their relations, but as other actors have found, this environment is inherently unstable and dangerous, where long-term guarantees mean little. Massive profits may be accrued quickly, but violence and perpetual crisis within many of Africa’s polities mean that the engagements China is pursuing in Africa will always be vulnerable. As a result, China may re-evaluate and reformulate its involvement. A more hands-on approach where both Chinese corporations and the state engage with domestic African situations is perhaps likely.

Any benefits Africa might generate from Chinese investment in the country depends on what Africans do for themselves far more than what Beijing might do for Africa. Acceptable governance is a precondition for the sorts of investment that are essential for Africa to move beyond being enclave oil-based economies or exporters of primary commodities.

Interestingly, it is usually accepted that a chief guarantee that an investment will advance the host country’s interests is the length of the engagement and the type of the investment. Enterprises that have fixed assets such as factories, mines, or other infrastructures associated with them, such as backward and forward linkages, have a much greater stake in stability and responsible government than do short-term opportunists or offshore investors. China’s heavy involvement in fixed infrastructure assets and investments mean that Chinese companies cannot stand aloof from the very real problems that characterise much of Africa. Ultimately, rather than competing with the West, China must converge with American policy aims in Africa, even if this is so far unacknowledged by Beijing. As Peter Lewis notes: ‘‘economic revitalization depends less upon specific policy remedies or a fortuitous external windfall than on a new political approach capable of shifting the central institutions and social coalitions toward good governance and economic growth’’.[31] Unless Beijing engages positively with Africa’s polities, confrontation with the dynamics of African politics might lead Chinese investors to retreat to the primary commodity sectors. China would then become just another actor in Africa’s enclave economies and non-industrialised sectors—a possibility, but wholly against Beijing’s rhetoric on mutual benefits and ‘win-win’ situations.

It is wildly unrealistic to pin Africa’s hopes on Beijing. But Chinese engagement with Africa often differs from America’s, because its interests are moving beyond offshore oilfields and primary commodities into the domestic economies, where Chinese actors are laying down permanent assets. I am not being overly optimistic in asserting that China can be a potential agent of change in Africa to be utilized in tandem with governance reform efforts. While Washington generally promotes governance rather than infrastructure enhancement and while governance, peace and security are crucial to Africa, reducing poverty and building infrastructure are critical to Africa’s development, which is where China may play its role. In such circumstances, the United States must engage Beijing in identified areas where mutual interests converge.

—

Ian Taylor is Professor in International Relations at the University of St. Andrews’ School of International Relations, a Joint Professor in the School of International Studies, Renmin University of China and an Honorary Professor in the Institute of African Studies, Zhejiang Normal University, China. He is also Professor Extraordinary in Political Science at the University of Stellenbosch, South Africa. His book, China’s New Role in Africa, is available from Lynne Rienner Publishers.

[1] Daniel Yergin The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money and Power (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1991).

[2] Michael Klare and Daniel Volman “The African “Oil Rush” and US National Security,” Third World Quarterly, vol. 27, no. 4 (2006); Michael Watts “Empire of Oil: Capitalist Dispossession and the Scramble for Africa,” Monthly Review, vol. 58, no. 4 (2006); John Ghazvinian Untapped: The Scramble for Africa’s Oil (London: Harcourt, 2007); and Duncan Clarke, D. Crude Continent: The Struggle for Africa’s Oil Prize (London: Profile Books, 2008).

[3] Ghazvinian, 2007, 12.

[4] Paul Roberts The End of Oil: The Decline of the Petroleum Economy and the Rise of the New Energy Order (London: Bloomsbury, 2004), 257.

[5] Ghazvinian, 2007, 8.

[6] Daniel Volman “The African Oil Rush and US National Security,” Third World Quarterly, vol.27, no.4, (2006), 611.

[7] Nicholas Shaxson Poisoned Wells: The Dirty Politics of African Oil (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2007), 24.

[8] Klare and Volman, “The African “Oil Rush,” 2006.

[9] Sandra Barnes “Global Flows: Terror, Oil and Strategic Philanthropy,” Review of African Political Economy, vol. 34, no. 104/5 (2005), 236.

[10] Cited in Cyril Obi “Globalization and Local Resistance: The Case of Shell Versus the Ogoni” in Lousie Amoore, ed. The Global Resistance Reader (London: Routledge, 2005), 39.

[11] Ibid., 38.

[12] Aluko Alao Natural Resources and Conflict in Africa: The Tragedy of Endowment (Rochester, NY: Rochester University Press, 2007), 168.

[13] Quoted in Daniel Volman “The Bush Administration and African Oil: The Security Implications of US Energy Policy,” Review of African Political Economy, vol. 30, no. 98 (2003), 76.

[14] Ghazvinian, 2007, 7.

[15] Although the actual quantity of African oil reserves are low in comparison to those presently found in the Middle East—proven oil reserves at the end of 2008 were 117 billion barrels in Africa, compared to 746 billion barrels in the Middle East—in a context marked by deep anxiety over future supplies, Africa’s reserves (c. 9% of the world’s total) are extremely significant—see Oil and Gas Journal, vol. 106, no. 48, December 22, (2008).

[16] Jedrzej Frynas and Manuel Paulo “A New Scramble for African Oil? Historical, Political, and Business Perspectives,” African Affairs, vol. 106, no. 423 (2007), 230.

[17] Ian Taylor “China’s Oil Diplomacy in Africa,” International Affairs, vol. 82, no. 5 (2006), 937.

[18] Michael Klare and Daniel Volman “America, China and the Scramble for Africa’s Oil,” Review of African Political Economy, vol. 33, no. 108 (2006).

[19] Stephen Ellis “Briefing: West Africa and its Oil,” African Affairs, vol. 102, no. 406 ( 2003), 135.

[20] Frynas and Paulo, 2007, 230.

[21] Ibid., 235.

[22] Ran Goel “A Bargain Born of Paradox: The Oil Industry’s Role in American Domestic and Foreign Policy,” New Political Economy, vol. 9, no. 4, (2004), 482.

[23] Quoted in confidential cable, ‘Subject: African Embassies Suspicious of US-China,’ February 11, 2010, accessed via Wikileaks.

[24] The PIB seeks to create a transparent administrative system, amending the Petroleum Profit Tax Administration, which currently treats information relating to company profits as confidential. The PIB also clarifies procedures for bidding processes and the retention of licences and leases and also simplifies collection of revenues by emphasising rents and royalties and less on taxes from petroleum. Furthermore, the PIB will compel companies to employ Nigerians in their employments and contract awards, especially on community related development projects.

[25] Confidential cable, ‘Subject: Chinese Oil Companies not so Welcome in Nigeria’s Oil Patch,’ February 23, 2010, US Embassy, Abuja, Nigeria, accessed via Wikileaks

[26] Ibid.

[27] Johnnie Carson, US assistant secretary for African Affairs, quoted in confidential cable, ‘Subject: Assistant Secretary Carson Meets Oil Companies in Lagos,’ February 23, 2010, US Consul, Lagos, Nigeria, accessed via Wikileaks.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Department of Energy Country Analysis Briefs: Nigeria (Washington DC: Department

of Energy, 2010), 4.

[31] Peter Lewis “Getting the Politics Right: Governance and Economic Failure in Nigeria”, in Robert Rotberg, ed., Crafting the New Nigeria: Confronting the Challenges (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2004), 100.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Global South in Times of Crisis: A China–Africa Relations View

- US-China Rivalry and the Future of Africa

- Opinion – The Status of China’s Confucius Institutes in American Universities

- Opinion – US-China Relations and the Perils of Historical Analogy

- Opinion – Emerging Elements of a New US-China Cold War

- Opinion – US Export Controls and China’s Semiconductor Industry