Introduction

A remarkable degree of concern has been expressed about levels of voter turnout in established democracies in recent decades. Titles such as The disappearing American voter or Where have all the voters gone?, and not to mention the “Vanishing voter project” of Harvard University, help to depict the frame into which this essay fits. Although there is disagreement over the size of the decline in turnout and on the importance that should be attributed to it, data brings general agreement on the fact that turnout at elections has declined in the decades following World War Two in many conventional democracies. This fact leads to somewhat of a paradox: never before has the Western world experienced higher levels of literacy and education, and never has it reached such high technological development, which enables information to be stored, accessed and circulated so rapidly and effectively; yet, these achievements are accompanied by a reduction in voting, arguably the simplest form of political participation. How can this be explained? Leading on from different areas of analysis, which for simplicity are divided into instrumental and cultural explanations, this investigation first reproduces the point of view of rational choice theory and strategic incentives; it then underlines its limits and adds factors of social capital and political culture which, as it concludes, appear to be quite precise and deep causal factors for the variation in voter turnout.

Key terms and measurements

For measurements of voter turnout, all data is based on the percentages of the voting age population (% VAP); processes of registration vary greatly across countries, and it would be difficult to consider differences in all of them. In regards to elections, the data used mainly refers to parliamentary elections, but for presidential systems it refers to presidential elections. In countries where both types of elections are held, data refers to the one that has produced greater turnout, usually being the presidential election.

A country is considered to have declining turnout if its average percentage levels in the last three decades have decreased by more than 2% compared to those of the first three decades. If comparison of these two time periods shows +2% increases, turnout is considered to have increased. Variation within the limits of +2% and -2% is considered stable turnout. For recent democracies, such strict rules do not apply because time periods of elections vary greatly.

The term ‘democratic country’ is used for countries that hold universal adult suffrage national elections regularly and are described as ‘free’ by the Freedom House. Conventional democracies are those that have been established before 1955. Countries that have compulsory voting are not considered for analysis. For conventional democracies, this includes Australia, Belgium, and Italy, but also Austria and the Netherlands, where voting has been legally enforced for a considerable part of the 20th century.

Decline in turnout

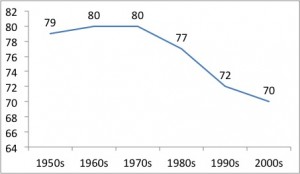

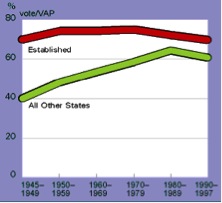

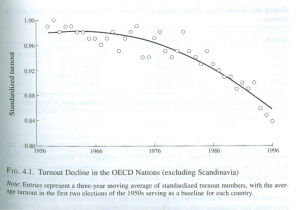

Table 1 compares average turnout in each decade since the 1950s in established democracies. Denmark, Sweden and Iceland show stable levels of turnout, while all other nations show declining figures. The average of all the countries considered shows a constant decline since the 1970s, with a total decline of 9 percentage points between the 1970s and the 2000s. Figure A graphs the average turnout in 19 old democracies and clearly shows the declining trend. Figure B shows turnout decline in OECD Nations. The pattern is surprising especially because it is unique to old democracies, seing that, as Figure 4 shows, turnout in other states has been growing steadily at least until the 1990s.

Some authors are not convinced that turnout really shows such a marked decline and argue that historical and institutional factors have to be considered, which would lead to a smaller figure; however, they, too, admit to the presence of a declining trend. Franklin, for example, who tends to be sceptical about the significance of this set of data, nonetheless, calculates a decline in turnout of 5.4% over 23 democracies[1]. This is by no means a small figure, especially considering that social patterns of behaviour evolve and change at very slow rates in time (this idea is discussed later in more detail). Having shown that voter turnout is generally declining in traditional democracies, we can now turn to possible explanations for this tendency.

What could explain the decline in turnout?

Part of the literature on the subject focuses on instrumental motivations and the institutional context by which elections take place[2]. When explaining the reasons behind a citizen’s decision to vote at elections, focus in this field is given to factors of proportionality, political competition, frequency of voting, voting days and registration processes. These are elements of the incentive structure available to the individual potential voter who, it is argued, when faced with the possibility of voting, weighs the costs and benefits and takes his or her decision accordingly, rationally. This idea is exemplified by, what is called, the rational choice equation R = BP – C.[3]

There are two main problems with this analysis: one is general and widely accepted and the other is more specific to our question. The first problem is what is known as the paradox of voting; the P term of the equation is statistically always very small, which causes the BP part of the equation to be smaller than C, consequently making voting appear irrational. The second problem is the inability of this argument to explain general trends of change in turnout across time: if the rational calculation argument is correct, such a widespread decline in turnout as the one noted above should have, at its roots, a general change in the incentive structure available to citizens.

Comparing electoral systems does not bring aid to the analysis, for there has certainly not been enough of a widespread move towards majoritarianism to explain the general decline[4]. Processes of electoral registration and voting procedures, and their associated costs, have generally declined with progress in technology and transport, which should have made even small benefits relatively greater compared to costs. It could be argued that parties are getting closer to each other ideologically, therefore, reducing the benefits of electing one for government instead of another. There is evidence from the Comparative Manifestos Project, however, that parties are not generally converging.[5] It would be plausible to believe that the outcome of elections is increasingly predictable before elections, which makes the contest less attractive to many voters, but there is no convincing data to state this. Generally speaking, it seems unlikely that institutional factors at a national or local level can have the combined effect of causing a reduction in turnout in such a high number of states.

More interestingly, Franklin forwards the idea that the decline recorded can be explained by the salience of elections in the western world, which has declined since the 1960s.[6] This is due mainly to the decline of class tensions, of labour vs. capital interests, and of the debate on the welfare state. Franklin does not suggest a way of measuring importance at elections, but his remains a plausible argument, especially in light of the fact that the decline in turnout starts precisely in the 1960s and ‘70s. We will return to this correlation.

Cultural explanations: the ‘D’ value, civic culture and culture shift

Having noted the limitations of the rational model equation, Riker and Ordeshook introduced an additional term to the model, bringing into consideration the satisfaction of fulfilling one’s role in the political and societal system[7]. R=BP+D-C was their new equation. We will refer to D generally as sense of civic duty, although this is reductive for what the authors had in mind[8]. If convinced of the strength of the argument and of its implications in explaining the puzzle we face, we can unfold it into two distinct, but related, paths: on one hand there is the concept of civic culture and on the other there is the idea of cultural shift.

D implies the presence of certain societal ties and forms of civic life, which cause the individual to feel he or she has a political role in the community; consequently, it feels legitimate, where needed, to consider D more generally as civic (or political) culture when referring not to the individual, but to society. Robert Putnam studies political culture in his Making Democracy Work. Political culture, for Putnam, is indicated by civic attitudes such as levels of newspaper readership and membership rates in secondary associations (e.g. trade unions). His main finding is that civic culture is a necessary prerequisite for positive institutional performance, of which an indicator is voter turnout. Civic culture is a predictor of institutional success (r=0.80), even more than economic development. He says, “at lower levels of development economies may matter, but at higher levels, politics counts for more”[9]. Such a statement seems to refer precisely to established democracies, suggesting that once they have reached a certain level of development, the effect of development on institutional success (and turnout) ends, and total levels of success decline (or go back to precedent ones), if not supported by a strong political culture.

The strength of the D element of the equation is stressed and proven also by Blais, Young and Lapp[10]. Their study focuses more strictly on the sense of duty in voters but comes to a clear conclusion that reinforces the thesis of Riker and Ordeshook and Putnam. Their finding is that, on citizens who claim to have a sense of duty to vote, the original rational equation gives no prediction of the voting outcome. The rational calculus of voting only helps to predict the voting behaviour of those who admit a weak sense of duty. Also, the answer of citizens when asked about their degree of interest in politics turns out to be a more powerful predictor of voting than the calculation of B, P and C. Although their study is limited to elections in Canada, the conclusions are certainly meaningful.

These results suggest that civic culture helps to explain declining turnout across democracies. To assess this, it is necessary to discover whether civic culture has declined in established democracies and the causal process that relates it to turnout. Almond and Verba describe civic culture as the sum of knowledge and awareness, political emotion and involvement, sense of political obligation and competence, and social attitudes and experiences[11]. Possible indicators of civic culture are sense of civic duty, attachment to political system and attachment to political parties[12].

Table 2 shows how party identification, with the exception of Denmark, has decreased in all established democracies. Quite significantly, Denmark also has experienced stable levels of turnout. The relationship between turnout and party Identification is shown in Table 3: Sweden and Iceland are the only two countries that do not fit with the general positive correlation between trends in party identification and turnout.

Attachment to the political system is largely documented by Dalton, who uses 43 indicators of attachment in 16 countries and finds 39 of them have declined. The measured confidence in political institutions in established democracies is shown in Table 4 and then related to turnout in Table 5. The result is very similar to the one shown by the correlation between party identification and turnout: Iceland is the only country with decreasing turnout that simultaneously registers growth in attachment to political institutions.

Sentiments of civic duty and political culture cannot be easily measured, and it is difficult to evaluate change in their influence on citizen’s behaviour. However, an influential strand of the literature on civic behaviour and political and institutional outcomes focuses on political culture to explain declining levels of traditional political participation. It is in the light of these arguments that we can introduce the idea of a cultural shift in post-industrial societies. Inglehart is the principal promoter of this concept, and his ideas are best described through the words of P. Norris:

“In conditions of greater security, Inglehart theorizes, public concern about the material issues of unemployment, health care and housing no longer takes priority. Instead, in post-industrial societies, the public has given increasingly higher priority to quality-of-life issues, individual autonomy and self-expression”[13].

The high levels of material well-being experienced by western societies have eroded the interest in economic factors of ‘survival’ and shifted the focus of individuals onto issues of personal well being. As Putnam notes, political systems have effects on communities, not on our “narrow-selves.”[14] Declines in participation and turnout are, therefore, due to the loss of trust in the political system, by which citizens do not feel represented.

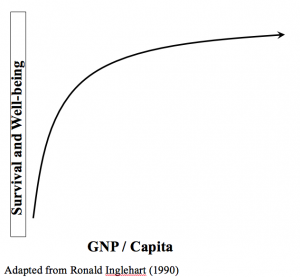

The cultural shift that Inglehart theorizes is specifically the one from modern to postmodern values. This involves moving from values and necessities of survival to values and desires of individual well-being and personal life satisfaction. Economic development has allowed modern societies to obtain a standard of living that secures survival and a minimum standard of well-being; having attuned to this wave of prosperity, societies of the west have developed new necessities and priorities, and this has influenced the modes of political participation. The shift from modern to postmodern values in relation to wealth is depicted in Figure 3. Table 6 measures the shift to postmodern values as being between the 1980s and 1990s.[15] Very interestingly, Iceland is the only country to register a negative shift in values. This could help to explain its position as an outlier in previous measurements of affiliation to party and political systems. Thus, the ideas of social capital and cultural shift to postmodern values seem to be effective in describing causal chains related to the decline in turnout in established democracies. In particular, they address sociological and cultural factors that, in opposition to institutional factors, can be plausibly regarded as common to a great part of western society.

In relation to the arguments made by Inglehart, an interesting observation can be made about the timing of events and trends that have been correlated in causal chains to explain declining levels of turnout. It has been noted already how Franklin suggests that the high turnout registered in the 1960s is related to the high importance of elections at that time. In fact, turnout seems to have started its decline precisely in those years, after having been at a peek in the ‘60s. It could be argued that the ‘60s and early ‘70s are precisely the years when old democracies had undergone the transition from modern to postmodern societies and started developing the values and needs that Inglehart describes. Testing this apparent coincidence to prove the argument would necessitate data on beliefs and values from the 70s at least, and it is not possible to do this with accuracy when looking in retrospect. The three trends do suggest, however, that the decline in turnout may have been partly caused by a reduction in the perceived importance of elections, which can be attributed to changes in the values and life priorities of individuals, as society began to adapt to different and higher levels of material well-being and security.

Conclusions

We should not be alarmist and exaggerated in describing the general trend in declining turnout across established democracies. As has been noticed, historical and institutional factors partly influence voting behaviour, yet, political participation continues to evolve into new and more specific forms[16], and it is very unlikely that citizens will abandon their power to influence political outcomes. At the same time, the persistence of the phenomenon over time should not be underestimated, particularly if we consider that cultural and sociological behaviour tend to constantly change, only at a very slow rate[17]. Though, declining turnout in the past forty years could be seen, pessimistically, as the beginning of a long-term deepening tendency.

Cultural explanations are largely successful in explaining the change in voter turnout that has occurred in the last four decades. While experiencing declining turnout, this period has also experienced decreasing levels of personal interest in politics and lowering levels of civic culture (including trust in political institutions and in the political system). Declining trust in traditional democratic institutions as vehicles for personal fulfilment and well-being has eroded the sentiment of civic duty.

The data available supports these patterns of social change. Data does not cover all periods of interest, and not all countries equally and is particularly deficient with regards to social indicators that are not easily quantifiable. As Stolle and Hooghe admit,

“Outside the United States, few long-term and reliable time-series are available. True, voter turnout, party and union memberships are well documented, but most informal forms of social interaction are not”[18].

The data that is available, however, is strikingly consistent in its results and can be effective in explaining cultural and behavioural trends.

Since the 1960s, there has been a shift in the priorities and values of western citizens who, by adapting to high levels of material well-being and abundant food and health security, have increasingly prioritised autonomy and individual quality-of-life issues over more basic economic necessities and class divisions. Traditional forms of community life and interaction have largely eroded, giving space to individualism and social isolation; the growth in interest groups and single-issue lobbies reflects the inadequacy of traditional party politics to address specific individual interests and concerns.

Such progressive shift to, as Inglehart describes them, postmodern values, is probably the deepest cause for declining turnout. It is the reason behind lower levels of civic and political culture, which, in turn, has caused decreasing confidence in political processes, a lower sense of civic duty and declining political engagement.

TABLE 1. Levels of Turnout from the 1950s to the 2000s

| 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | Trend | |

| Canada | 70 | 72 | 68 | 67 | 60 | 56 | – |

| Denmark | 78 | 87 | 86 | 85 | 82 | 83 | = |

| Finland | 76 | 85 | 82 | 79 | 70 | 69 | – |

| France | 71 | 67 | 67 | 64 | 61 | 50 | – |

| Germany | 84 | 83 | 86 | 79 | 74 | 73 | – |

| UK | 79 | 74 | 74 | 73 | 72 | 58 | – |

| Iceland | 91 | 89 | 89 | 90 | 87 | 87 | = |

| Ireland | 74 | 74 | 82 | 76 | 70 | 68 | – |

| Israel | 79 | 82 | 81 | 81 | 85 | 86 | – |

| Japan | 74 | 71 | 72 | 71 | 67 | 62 | – |

| New Zealand | 91 | 84 | 83 | 86 | 79 | 76 | – |

| Norway | 78 | 83 | 80 | 83 | 76 | 76 | – |

| Sweden | 77 | 83 | 87 | 86 | 81 | 79 | = |

| Switzerland | 61 | 53 | 61 | 40 | 36 | 39 | – |

| US | 59 | 62 | 54 | 52 | 53 | 55 | – |

| (average) | 76.1 | 76.6 | 76.8 | 74.1 | 70.2 | 67.8 |

Source: Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, www.idea.int.

FIGURE A. Declining turnout in 19 old democracies.

Sources:

Dalton, Russell J., Citizen Politics: Public Opinion and Political Parties in Advanced Industrial Democracies, 5th edition (Washington DC: CQ Press, 2008), p. 37.

International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, “Voter Turnout Database”, International IDEA website.

FIGURE B: Turnout Decline in the OECD Nations (excluding Scandinavia)

Source: Dalton, Russel J., “The Decline of Party Identifications”, in Russell J. Dalton and Martin P. Wattenberg (eds.), Parties without Partisans: Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), p 73.

TABLE 2: Trends in Party Identification

| % with Party ID | % Identifiers | sig | Period | |

| UK | 93 | -0.189 | .01 | 1964-97 |

| Canada | 90 | -0.386 | .05 | 1965-97 |

| Denmark | 52 | 0.001 | .95 | 1971-98 |

| Finland | 57 | -0.293 | .49 | 1975-91 |

| France | 59 | -0.670 | .00 | 1975-96 |

| Germany | 78 | -0.572 | .00 | 1972-98 |

| Iceland | 80 | -0.750 | .08 | 1983-95 |

| Ireland | 61 | -1.700 | .00 | 1978-96 |

| Japan | 70 | -0.386 | .06 | 1962-95 |

| New Zealand | 87 | -0.476 | .01 | 1975-93 |

| Norway | 66 | -0.220 | .34 | 1965-93 |

| Sweden | 64 | -0.690 | .00 | 1968-94 |

| US | 77 | -0.366 | .00 | 1952-96 |

Source: Dalton, Russel J., “The Decline of Party Identifications”, in Russell J. Dalton and Martin P. Wattenberg (eds.), Parties without Partisans: Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), p 25.

TABLE 3: Turnout and Party ID

|

DECLINING Party Identification |

STABLE/GROWING Party Identification |

|

| DECLINING Turnout |

Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, UK, US. |

|

| STABLE/GROWING Turnout |

Iceland |

Denmark, Sweden

|

Sources: Dalton, Russell J. and Wattenberg, Martin P. (eds.), Parties without Partisans: Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), p 25. www.idea.int for voter turnout.

TABLE 4: Confidence in Political Institutions

| 1981-84 | 1990-93 | Change | |

| Canada | 61 | 46 | -15 |

| Denmark | 63 | 66 | +3 |

| Finland | 72 | 53 | -19 |

| France | 57 | 56 | -1 |

| Germany | 55 | 53 | -2 |

| UK | 64 | 60 | -4 |

| Iceland | 62 | 63 | +1 |

| Ireland | 66 | 61 | -5 |

| Japan | 46 | 41 | -5 |

| Norway | 75 | 66 | -9 |

| Sweden | 61 | 54 | -7 |

| US | 63 | 56 | -7 |

| (Average) | 62 | 56.3 | -5.7 |

Source: Russell Dalton, “Political Support in Advanced Industrial Democracies”, Center for the Study of Democracy, UC Irvine, 01-15-1998, p 10, available at http://escholarship.org/uc/item/8281d6wt.

TABLE 5: Turnout and Confidence in Political Institutions

|

DECLINING Confidence in Political Instit. |

STABLE/GROWING Confidence in Political Instit. |

|

| DECLINING Turnout |

Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, UK, US |

|

| STABLE/GROWING Turnout |

Iceland |

Denmark

|

Sources: Dalton, “Political Support in Advanced Industrial Democracies”, p 10, and World Values Survey (see www.worldvaluessurvey.org) for confidence in political institutions. www.idea.it for voter turnout.

FIGURE 3: Shift from Modern to Postmodern Values in Relation to Wealth

Source: Ronald Inglehart, Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society, (Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, 1990)

TABLE 6: The Shift Towards Postmaterialist Values

| 1981 | 1990 | Net shift | |

| Finland | 21 | 23 | +2 |

| Canada | -6 | 14 | +20 |

| Iceland | -10 | -14 | -4 |

| Sweden | -10 | 9 | +19 |

| Germany | -11 | 14 | +25 |

| UK | -13 | 0 | +13 |

| France | -14 | 4 | +18 |

| Ireland | -20 | -4 | +16 |

| Norway | -21 | -19 | +2 |

| US | -24 | 6 | +30 |

| Japan | -32 | -19 | +13 |

Source: Ronald Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1997), p 157.

Figure 4: Differences between established democracies and other states over time

Key: VAP = voting age population

Source: www.idea.int

Bibliography

Almond, Gabriel A., and Verba, Sidney, The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations (Boston, Mass.: Little, Brown & Co., 1963).

Dalton, Russell J., Citizen Politics: Public Opinion and Political Parties in Advanced Industrial Democracies, 5th edition (Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 2008).

Dalton, Russell J., Flanagan, Scott C., et al., eds., Electoral Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies: Realignment or Dealignment? (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984).

Dalton, Russel J., “The Decline of Party Identifications”, in Dalton, Russell J. and Wattenberg, Martin P. (eds.), Parties without Partisans: Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Dunleavy, Patrick, Democracy, Bureaucracy and Public Choice : Economic Explanations in Political Science (London: Harvester, 1991).

Franklin, Mark N., “The Dynamics of Electoral Participation”, in LeDuc, Lawrence, Niemi, Richard G., Norris, Pippa, eds., Comparing Democracies 2: New Challenges in the Study of Elections and Voting (Thousand Oaks ; London : Sage, 2002), p 148-168.

Inglehart, Ronald, Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society, (Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press,1990).

Inglehart, Ronald, Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1997).

Inglehart, Ronald, The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles Among Western Publics, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977).

Lane, Robert, The Loss of Happiness in Market Democracies (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2000).

LeDuc, Lawrence, Niemi, Richard G., Norris, Pippa, eds., Comparing Democracies 2: New Challenges in the Study of Elections and Voting (Thousand Oaks ; London : Sage, 2002).

Norris, Pippa, Electoral Engineering: Voting Rules and Political Behavior (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Putnam, Robert, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000).

Putnam, Robert, Making Democracy Work : Civic Traditions in Modern Italy (Princeton : Princeton University Press, 1993).

Journals:

Blais, Andre’, Young, Robert, and Lapp, Miriam, ‘The Calculus of Voting: An Empirical Test’, European Journal of Political Research, 37, 2 (1998), 239-261.

Riker, William H. and Ordeshook, Peter C., ‘A Theory of the Calculus of Voting’, American Political Science Review, vol. 62, 1 (1968), 25-43.

Stolle, Dietlind and Hooghe, Marc, ‘Review Article: Inaccurate, Exceptional, One-Sided or Irrelevant? The Debate about the Alleged Decline of Social Capital and Civic Engagement in Western Societies’, British Journal of Political Science, 35, 1, (January, 2005), 149-167.

Electronic sources:

Comparative Manifestos Project, http://www.wzb.eu/zkd/dsl/Projekte/projekte-manifesto.en.htm

International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, ‘Voter Turnout Database’, International IDEA website, http://www.idea.int/vt/

[1] Mark N. Franklin, ‘The dynamics of electoral participation’, in LeDuc, Lawrence, Niemi, Richard G., Norris, Pippa, eds., Comparing Democracies 2: New Challenges in the Study of Elections and Voting (Thousand Oaks ; London : Sage, 2002), p 163.

[2] See, for example, the works on the subject by Tingsten, Powell, Crewe and Jackman.

[3] R is the reward obtained from voting, P is the probability of changing the outcome of the election, B are the benefits from the election of the preferred candidate, and C are the costs of voting.

[4] There have been movements towards proportionality in France (1985), New Zealand (1993), and Scotland (1999), and away from proportionality in France (1986), Italy (1993) and Japan (1994), but there is certainly no general shift.

[5] See the Comparative Manifestos Project at http://www.wzb.eu/zkd/dsl/Projekte/projekte-manifesto.en.htm

[6] Mark N. Franklin, “The Dynamics of Electoral Participation”, p 163-164.

[7] William H. Riker and Peter C. Ordeshook, ‘A Theory of the Calculus of Voting’, American Political Science Review, vol. 62, 1 (1968), p 28.

[8]Duty implies a form of obligation, while Riker and Ordeshook represent D as the personal “satisfaction from complying with the ethic of voting” and “affirming allegiance to the political system”, p 28.

[9] Robert Putnam,, Making Democracy Work : Civic Traditions in Modern Italy (Princeton : Princeton University Press, 1993), p 66.

[10] Andre’ Blais, Robert Young, and Miriam Lapp, ‘The Calculus of Voting: An Empirical Test’, European Journal of Political Research, 37, 2 (1998).

[11] Almond, Gabriel A., and Verba, Sidney, The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations (Boston, Mass.: Little, Brown & Co., 1963), p 402.

[12] “Since partisanship also mobilizes individuals to participate in politics”, writes Dalton in Dalton, Citizen Politics: Public Opinion and Political Parties in Advanced Industrial Democracies, 5th edition (Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 2008), p 192. And he continues: “[…]it is no surprise that [party] dealignment has been accompanied by a decline in electoral participation”.

[13] Pippa Norris, Electoral Engineering: Voting Rules and Political Behavior (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p 19.

[14] Robert Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000), p 184.

[15] Ronald Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1997), p 157.

[16] “A myriad of special-interest groups and single-issue lobbies have developed in recent years and political parties have little hope of representing all of them”. Dalton, Citizen Politics, p 193.

[17] “Cultural accounts emphasize that habitual patterns of electoral behavior evolve slowly and incrementally” writes Pippa Norris in Norris, Electoral Engineering: Voting Rules and Political Behavior (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p 20.

[18] Dietlind Stolle and Marc Hooghe, ‘Review Article: Inaccurate, Exceptional, One-Sided or Irrelevant? The Debate about the Alleged Decline of Social Capital and Civic Engagement in Western Societies’, British Journal of Political Science, 35, 1, (January, 2005), p 165.

—

Written by: Luca Ferrini

Written at: University of Reading

Written for: Jonathan Golub

Date written: November 2010

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- South Korea Is Not In Democratic Backslide (Yet)

- Why Is Identity Politics Failing to Curb Social Injustice?

- Why Do Some Social Movements Succeed While Others Fail?

- Interregionalism Matters: Why ASEAN Is the Key to EU Strategic Autonomy

- Neopatrimonialism and Democratic Consolidation in Nigeria

- The Protection Paradox: Why Security’s Focus on the State Is Not Enough