Introduction

Traditional approaches to international relations have consistently neglected certain global issues in their analyses. One such topic is global migration, an issue occupying a substantial part of state practice yet only marginally addressed and problematised in traditional IR theory.[1] This essay will attempt to critically analyse asylum and refuge, a central issue within the wider scope of migration, and answer a difficult question: can states and societies absorb refugees and asylum-seekers and still maintain their security?

To answer this question I will examine the case study of Israeli state practices regarding African asylum-seekers, mainly from Sudan and Eritrea. I hope to prove that exclusionary practices towards asylum-seekers emerge primarily as a result of a process of collective identity construction which creates an image of these refugees as a ‘threat’, thus marginalising them and revoking their agency in the name of ‘national security’. As long as this process is left unattended, the reality constructed as its aftermath cannot allow for the successful absorption of refugees which are categorised as ‘others’.

This essay will refer in many cases to state practices to provide evidence of the implications of collective identity and ‘othering’. This does not mean that the state is a unitary actor, as can clearly be demonstrated from the Israeli case study; however, this essay will refer to the state as such to avoid confusion, as the practices presented are applied by the state mechanism, often with no discernible individual or group behind them. Practices and positions that diverge among different actors within the state mechanism will be clearly identified.

This essay begins by formulating a theoretical framework that identifies how the process of the marginalisation of the refugee works. This will be based on literature from the field of biopolitics and critical border studies, combined with case-specific arguments from ethnonationalist theory. It will then analyse the historical evolution of the African refugee situation in Israel and how the identity of the refugee was constructed to allow for their marginalisation, through examples taken from Israeli state practice and public discourse. Finally, this paper will examine some existing moral, legal and political alternatives within policy research and offer an insight as to the fundamental transformations required for them to succeed.

In order to focus my research on one specific phenomenon of migration, this paper will not discuss Palestinian and Arab refugees in this essay[2], nor will it be elaborating on Jewish migration or non-Jewish explicit labour migration, legal or otherwise. Also, in an attempt to maintain a certain level of consistency, it will refer to the subjects of my case study, citizens of African countries migrating to Israel in recent years, as asylum-seekers or refugees alternatively, in accordance with existing definitions of international law.[3]

A Theory of Marginalising the Refugee

Collective identities (including nationality and ethnicity) are socially constructed over time and are (re)inforced through political practices which serve to emphasise the differences between the ‘in-group’ (‘us’/’self’) and the ‘out-group’ (‘them’/’other’).[4] The ‘other’ is constantly (re)constituted through the (re)shaping of the identity of the ‘self’, which always needs an ‘other’ to serve as its boundary and its threat and vice-versa.[5]

The concept of borders has an important role in the (re)construction of such identities and categorisations of in/out-groups.[6] “[B]orders determine the nature of group (in some cases defined territorially) belonging, affiliation and membership, and the way in which the processes of inclusion and exclusion are institutionalized”[7]; they delineate one group from another. Borders do not have to be physical nor permanent; the concept of ‘border’ is constantly changing and evolving, from a thin line on a map to a nexus of policies, practices and social understandings.[8] Borders are performatively created to distinguish between the ‘worthy’ within and the ‘bare life’ on the outside; they are the place where the migrant as an ‘out-group’ is given their collective identity.[9]

A flow of migrants usually serves to disrupt the dichotomy between ‘us’ and ‘them’ that is necessary to ensure the existence of any society, as ‘others’, often in large quantities, suddenly attempt to ‘cross’ the border and become part of the ‘in-group’. State practices will frequently attempt to reinforce existing distinctions between the in/out groups and signal to the ‘others’ that they are not welcome, while at the same time perforate these distinctions through an incorporation of ‘others’ into domestic society which dictated by international law.[10]

Certain groups are collectively categorised according to their level of ‘risk’ to the host state and society.[11] When classifying migrants, state authorities will examine both the legality of the migrants’ entry/stay in the host state and the level of freedom exercised in their decision to migrate. The mere act of classification is what empowers the state and the majority groups within society[12]; it allows the powerful to determine who among those knocking on the country’s doors is ‘bare life’ and thus ‘worthy’ of the mercy of the state, in the sense that he/she are, subject to its arbitrary authority and denied of agency.[13] Consequently, forced migrants like refugees and asylum-seekers, by the mere act of their categorisation under those labels, become ‘bare life’: saved from dying without gaining agency.[14] Those who attempt to show any signs of agency, for example protest or evade the authorities, are labelled ‘frauds’, ‘criminals’ or ‘potential terrorists’ in order delegitimise their presence within the state’s borders.[15]

Asylum-seekers can therefore be criminalised according to the legality of their arrival to the host country, should the state decide this criterion to be more important than that of ‘free choice’. In such cases, migrants crossing the border illegally are immediately labelled as ‘criminals’ and risk being deported even if they have a genuine claim to asylum.[16] This raises a legal and moral problem: according to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (hereinafter ‘1951 Convention’), while there is no universal obligation to grant asylum, it is considered unacceptable to deny anyone the opportunity to claim asylum.[17]

Fear of the ‘other’ is a powerful element in social life since it immediately invokes the fear of losing or changing the identity of the collective ‘self’.[18] Political and social elites often take advantage of this fear to invoke “the very notion of a community that is endangered by migration”[19] in order to garner support for exclusionary practices against “those migrants who are identified as cultural aliens”[20]. Thus, elites often attempt to make the connection between groups of ‘others’ (like asylum-seekers) and social threats such as drug trade, crime, sexual violence, infectious diseases and terrorism.[21] These accusations, as evident in this case study, can be ‘self-fulfilling prophecies’ as marginalisation by society leads asylum-seekers to connect with other marginalised groups and survive through crime.

In liberal democracies, the politics of insecurity born out of the collective marginalisation of migrants and their categorisation as a ‘threat’ can lead to exceptionalist practices – special decrees, ’emergency regulations’, speedy legislative or bureaucratic processes and hyper-patriotic calls for ‘unity’ – which usually favour a concentration of power within the administrative branch and government bureaucracy under the self-defeating purpose of ‘protecting democracy’.[22] These illiberal practices are intensified in societies categorised as ‘ethnocracies’, a regime type which “facilitates the expansion, ethnicization, and control of a dominant ethnic group… over contested territory and polity”.[23] Most ethnocracies emerge following a culmination of certain historical processes: the creation of a ‘frontier culture’ to justify expansion; the development of the nation-state as the exemplar of ethnic self-determination; and an economic stratification process which generates a correlation between ethnonational and economic-class divisions.[24]

Liberal democratic institutions and the rule of law in ethnocracies is usually a facade for an undercurrent of illiberal control practices by the dominant ethnic group.[25] This facade, which is able to resist moderate migration through either exclusion or immersion, tends to break completely following large waves of migration and illiberal exclusionary practices surface more easily than in actual liberal democracies.

Israel and African Refugees/Asylum-seekers

Before examining the specific case study of African refugees in Israel, some background is needed to better understand Israeli society’s approach to non-Jewish migrants. Israel’s economic success required the import of cheap labour to support its labour-intensive sectors (mainly agriculture and construction). Since 1967 Palestinian workers from the Occupied Palestinian Territories filled this role, yet after the 1987 Intifada Israel heavily restricted their work permits. Reluctantly and under heavy pressure from powerful interest-groups, the Israeli government began importing foreign migrant workers to fill the gap left by the Palestinians.[26]

Due to Israel’s blood-based naturalisation laws, these labour migrants can never receive permanent residence and they remain “on the fringes of society”.[27] This presence of labour migrants had led to limited expressions of xenophobia even before asylum-seekers from Africa began arriving in large quantities, yet these acts demonstrated economic concerns more than anything else.[28]

Jewish Identity, Ethnocracy and the Discourse of Asylum in Israel

Israel, due to the historical experience of the Holocaust, had been one of the main advocates for the 1951 Convention and was one of the first states to ratify it (1954)[29], yet it had never officially incorporated the Convention into domestic law; in fact, until 2006 Israel did not even have an organised asylum system (despite occasional demonstrations of good-will towards refugees[30]) and it had relied on UNHCR representatives to process the small amount of asylum requests applied every year.[31]

From 2006 onwards non-Jewish migration to Israel began to change. The civil war in Sudan and the genocide in Darfur caused a massive flight of Sudanese (including South Sudanese and Darfurians) from Sudan[32]; in addition, tens of thousands of Eritrean citizens have fled their country due to religious persecution[33] and the cruel and abusive mandatory conscription in the country.[34] When neighbouring countries such as Egypt[35] and Ethiopia proved to be unsafe, many asylum-seekers decided to take the perilous journey through the Sinai desert towards Israel, using Bedouin smugglers and traffickers against which Israel has been fighting for decades.[36]

The migrants entering Israel through the Sinai border were mostly poorly educated, unemployed, young, single men; a different demographic than the non-Jewish migrants Israeli society had encountered in the past.[37] The numbers were also different: Since 2006 and until the end of 2012 numbers of African refugees and asylum-seekers crossing the long and porous Israeli-Egyptian border have risen to several thousand each year, resulting in over 55,000 residing in Israel as of March 2013.[38] This ‘flooding’ of the Israeli-Egyptian border with migrants, and not the continuous smuggling of drugs, weapons, sex workers and terrorists across the border[39], had ignited intense public debates and determined state action.

The panic in Israel over rising numbers of non-Jewish migrants should be analysed through the concept of Jewish collective identity. Israel is defined both as a Jewish (ethno-religio-nationalist) state and as a liberal-democratic state which adheres to international law and international humanitarian standards (if the Occupied Palestinian Territories are excluded[40]). Ever since its inception, Israel has made every effort to maintain a Jewish majority in the state which was created after the Holocaust to provide a ‘home for the Jewish people’.[41] Consequently, in Israel the ‘otherness’ of the ‘other’ is extremely emphasised and perpetuated, often through racial and ethnic profiling, in order to revoke the non-Jewish ‘other’ of any opportunity to be absorbed in Israeli society over time and threaten the salience of the Jewish religio-ethnic collective identity.[42]

Historically, “Israel is perceived… as… a repatriation state, and not as an immigration state… Immigration appeared to be a ‘like all other countries’ concept that is unsuited to the specific Israeli reality and the Zionist vision”.[43] This vision, however, has become irrelevant in this context and for the first time in its short history, Israel is becoming more like other societies which unwillingly attract immigration. This has led to a change in the security discourse in Israel.[44]

Israel is often defined as an ‘ethnocracy’ in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict[45]; however, this categorisation is also relevant for analysing non-Jewish migration. In the words of Haim Yacobi: “the flow of non-Jewish, non-white, migrants into Israel is having a significant impact in the Israeli ethnocratic context”[46] since another group is now forced to compete over limited resources against the Jewish-white majority and the various (Jewish and non-Jewish) minorities.[47] Despite the materialistic approaches implied by ethnocratic theory, it is still useful in understanding Israel’s dilemma between its ethnocratic nature and collective identity and between its obligations to international law[48], thus contributing to a better understanding of Israeli practices towards African refugees.

Border Practices, Collective Identities and Agency

African Asylum-seekers (mostly Sudanese and Eritreans) crossing the Israeli-Egyptian border are usually arrested by Israeli Border Patrol and led to a detention center for initial processing[49] (should they manage to avoid a deadly encounter with the Egyptian Border Police[50]). Yet their hopes of asylum are usually shattered quite quickly: asylum-seekers from Sudan, officially an ‘enemy state’ of Israel, are denied the possibility to claim asylum, allegedly in accordance with the 1951 Convention[51]; as for Eritreans, Israel denies Eritrea being under the scope of the 1951 Convention (perhaps due to the good relationship between the two countries) and Eritreans entering Israel are also collectively denied of applying for asylum.[52]

The UN, however, prohibits Israel from deporting these asylum-seekers back to their home countries or to their first-host (Egypt)[53] for fear of their safety: in Sudan they are expected to be executed for visiting an enemy state and in Eritrea incarcerated indefinitely for avoiding conscription. Consequently, they are given a status of ‘temporary collective protection’ which prevents Israel from deporting them until decided otherwise[54] and are released without permission to work legally (although authorities regularly turn a blind eye to undocumented employment[55]).

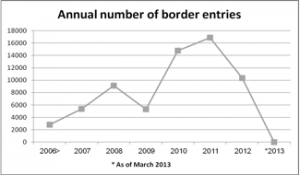

When in 2009 the Israeli government finally realised the severity of the situation, it abandoned the arrangement it had with the UNHCR and ‘nationalised’ the asylum process.[56] However, because Sudanese and Eritrean nationals are denied the right to claim asylum, this process remains under-developed. Instead, the Israeli government initiated several other projects designed to ‘solve the problem’. First, it decided to build a ‘smart’ fence stretching across all of the Israeli-Egyptian border, thus coercing asylum-seekers to choose the dangerous mountain route close to the red-sea city of Eilat as their crossing point in hope of dissuading them from crossing altogether[57]; construction of this fence is currently at its final stages and it has already diminished the number of border crossings to much lower numbers than in the past (as can be seen in chart 1).[58]

Chart 1: Number of ‘infiltrators’ (official Israeli term) in Israel[59]

Second, the government had removed the ‘temporary collective protection’ from citizens of the newly-founded South Sudan and arranged for their ‘agreed repatriation’[60]; similar efforts were made to ‘repatriate’ Eritrean and Sudanese citizens, yet the Israeli Supreme Court and the UN have mostly been able to prevent this.[61] Third, the 1954 Prevention of Infiltration Law, originally drafted to protect newborn Israel from Palestinians and other Arabs crossing its borders (for personal, economic or military purposes), was recently amended to allow the state to arrest ‘infiltrators’ of any nationality upon entry for up to three years without trial, regardless of their right to claim asylum and in violation of international law.[62] However, this amendment had been suspended due to pending review of the entire law by the Supreme Court.[63]

To add to these official state practices, a coordinated xenophobic and dehumanising campaign was initiated by ministers, members of Knesset and senior academics and journalists against what they collectively called ‘infiltrators’, implying to the asylum-seekers illegality. This campaign included rallies where Knesset (Israeli Parliament) members compared ‘Sudanese’ to ‘cancer’[64]; state-funded academic papers insisting asylum-seekers from Sudan and Eritrea are nothing more than labour migrants in disguise[65]; a statement by then Minister of Interior Eli Yishay blaming African ‘labour migrants’ of spreading infectious diseases[66]; and a provocative election video by the ultra-orthodox ‘Shas’ party, leaked prematurely and then abandoned, which attempted to gain electoral capital from Jewish fear of the ‘other’[67]. Cases of violence by Eritrean and Sudanese nationals, including one case of an Eritrean citizen arrested for assisting a Palestinian terrorist money smuggling network, served as additional fuel to the fire[68] and have triggered counter-acts of violence against black people in Tel-Aviv, some of which were actually Ethiopian Jews.[69]

All of the practices above, whether applied by the state or otherwise, have a common goal: to construct a certain collective identity of African asylum-seekers and refugees without addressing their individual personal claims for asylum.[70] Even in the rare cases where the government had agreed to grant a limited amount of permanent refugee or temporary work visas to African asylum-seekers, it had done so on a collective basis and without actually examining the asylum requests on a case-by-case basis.[71] This collective view of African asylum-seekers is meant to create a border between them and the Jewish majority; they are collectivised so they can be marginalised and revoked of agency.

Exclusionary language, exclusionary practices

As a country facing permanent threats from its immediate environment, Israeli society and the state are hyper-sensitive to any phenomenon that might pose as a threat to its perceived security. Security is a major part in the collective identity of Israelis and it is only natural to assume that a massive illegal entry of ‘others’, especially citizens of an ‘enemy state’ such as Sudan, would be treated with alarm. The language applied in the asylum discourse by government officials and the media, however, only serves to intensify this alarm and justify exclusionary practices: the use of the term ‘flood’ to describe asylum-seekers entering Israel implies to the challenge it poses to the authority of the state in ‘securing’ its borders[72]; implicit comparisons between asylum-seekers and Palestinians, either through the label attached to asylum-seekers (‘infiltrators’) or the language portraying the new border fence (similar to the language used for the West Bank wall)[73], create a negative collective image of asylum-seekers as security threats; the use of diseases, both as linguistic metaphors and as actual warnings, dehumanises those who escaped impossible life conditions and even Genocide.

The discourse serves its purpose: popular fear has justified exclusionary state practices that have delegitimised the very presence of African refugees in Israel and pushed them to live on the fringes of Israeli society, working illegally (if at all), surviving in many cases through crime and constantly fearing arrest, deportation or mob violence.

Conclusions and Suggested Solutions

“Many people – many nations – can find themselves holding, more or less wittingly, that ‘every stranger is an enemy’. For the most part this conviction lies deep down like some latent infection… But when this does come about, when the unspoken dogma becomes the major premiss in a syllogism, then, at the end of the chain, there is the lager”.[74]

Many exclusionary and illiberal practices mentioned above – conflation of asylum-seekers with economic migrants, deportation, protracted detention, dispersal and fortification of borders – are today ‘normalised’ worldwide and regarded as legitimate by many Western countries, in contradiction of international law.[75] Israel’s attempts to follow this trend can be explained through its unique characteristics – a single Jewish state surrounded by weak enemy states, one of the only developed states in the world with a positive population growth rate and an over-populated country with weak minority communities and many existential threats – which make it extremely sensitive to (non-Jewish) migration in general and clandestine border-crossings in particular.[76]

Nevertheless, there are voices who suggest that Israel should deviate from the global trend. Israel is a state which has sworn to fight genocide worldwide and prevent ‘another Holocaust’. The poor global standards of treating refugees should not serve as an example for Israel of ‘what to do‘ but rather of ‘what not to do‘.[77] Adherence after ‘normalised’ exclusionary practices, coupled with the tremendous strain of the occupation of the West bank, could deteriorate Israel’s already-fragile moral standing to very dangerous places. The maintenance of a Jewish majority in Israel needs to be taken in perspective and should not be achieved at any price. Israel should differentiate itself from other states and their practices and adopt “a policy that reflects sensitivity and openness… toward authentic cases of refugees and asylum seekers”.[78]

This essay cannot contain all possible policy recommendations. Most of the humane and moral options for improving state practice – completing the fence, introducing asylum quotas and improving access for asylum-seekers to Israeli embassies in first-host countries – have been covered by a position paper written by Avineri, Orgad and Rubinstein.[79] However, any policy recommendation should to be founded upon the abolition of collective marginalisation of asylum-seekers already living in Israel and an adoption of an individualistic case-by-case approach. That will both allow new asylum requests and give existing asylum-seekers access to work and limited social benefits while their application is considered. Legislation, media coverage, administrative orders by government officials and elite rhetoric should also adopt an inclusive agenda and avoid collective derogatory, dehumanising and criminalising labelling.

Bibliography

Academic Articles and Books

Afeef, Karin Fathimath, “A promised land for refugees? Asylum and migration in Israel”, New Issues in Refugee Research, Research Paper No. 183, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Policy Development and Evaluation Service (December 2009)

Andrijasevic, Rutvica, “From Exception to Excess: Detention and Deportations across the Mediterranean Space”, in Nicholas de Genova and Nathalie Peutz (eds.), The Deportation Regime: Sovereignty, Space, and the Freedom of Movement (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010)

Avineri, Shlomo, Liav Orgad and Amnon Rubinstein, Managing Global Migration: A Strategy for Immigration Policy in Israel, The Metzilah Center for Zionist, Jewish, Liberal and Humanist Thought Position Paper (2010), available at http://www.metzilah.org.il/webfiles/fck/file/Immi_Book%20final.pdf (accessed 4/4/2013)

Ben-Dor, Anat, “Refugees and Asylum-seekers – Unwelcomed Guests in the State of Israel: Information Page” (in Hebrew), Tel Aviv University Legal Clinics, available at http://www.law.tau.ac.il/Heb/?CategoryID=499&ArticleID=723 (accessed 21/3/2013)

Bloch, Alice and Liza Schuster, “At the extremes of exclusion: Deportation, detention and dispersal”, Ethnic and Racial Studies, Vol. 28, No. 3 (May 2005)

Campbell, David, Writing Security: United States Foreign Policy and the Politics of Identity, Revised Edition (Manchester, UK: University of Manchester Press, 1998)

Canetti-Nisim, Daphna and Ami Pedahzur, “Contributory factors to Political Xenophobia in a multi-cultural society: the case of Israel”, International Journal of Intercultural Relations, Vol. 27 (2003)

Dawson, Carrie, “On Thinking Like a State and Reading (about) Refugees”, Journal of Canadian Studies, Vol. 45, No. 2 (Spring 2011)

Doty, Roxanne Lynn, “Desert Tracts: Statecraft in Remote Places”, Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, Vol. 26, No. 4, Race in International Relations (October-December, 2001)

Doty, Roxanne Lynn, “Immigration and the politics of security”, Security Studies, Vol. 8, Nos. 2-3 (1998)

Doty, Roxanne Lynn, “The Double-Writing of Statecraft: Exploring State Responses to Illegal Immigration”, Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, Vol. 21, No. 2 (April-June 1996)

Farrier, David, “Everyday Exceptions: The Politics of the Quotidian in Asylum Monologues and Asylum Dialogues”, Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies, Vol. 14, No. 3 (2012)

Guild, Elspeth and Joanne van Selm (eds.), International Migration and Security: Opportunities and Challenges (Abingdon: Routledge, 2005)

Huysmans, Jef, “Minding Exceptions: The Politics of Insecurity and Liberal Democracy”, Contemporary Political Theory, Vol. 3 (2004)

Jones, Reece, “Border security, 9/11 and the enclosure of civilisation”, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 177, No. 3 (September 2011)

Kritzman-Amir, Tally and Yonatan Berman, “Responsibility Sharing and the Rights of Refugees: The Case of Israel”, The George Washington International Law Review, Vol. 41, No. 3 (October 2010)

Kritzman-Amir, Tally, “”Otherness” as the Underlying Principle in Israel’s Asylum Regime”, Israel Law Review, Vol. 42, No. 3 (January 2009)

Levi, Primo (trans. Stuart Woolf), “Author’s Preface”, If This is a Man and The Truce (London: Abacus, 1987)

Martins, Bruno Oliveira, Undocumented Migrants, Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Israel, EuroMeSCo Paper No. 81 (February 2009)

Mor, Zohar, Itamar Groto and Alex Leventhal, “Tuberculosis and AIDS in Immigrants – is that so?” (Hebrew), The Medicine (Ha’REfua), Vol. 151, No. 3 (March 2012)

Natan, Gilad, “Treatment of Infiltrators from the Egyptian Border” (Hebrew), Knesset Research and Information Center, 26 May 2010

Newman, David, “The lines that continue to separate us: borders in our ‘borderless’ world”, Progress in Human Geography, Vol. 30, No. 2 (2006), p. 147, emphasis added

Paz, Jonathan, “Ordered disorder: African asylum-seekers in Israel and discursive challenges to an emerging refugee regime”, New Issues in Refugee Research, Research Paper No. 205, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Policy Development and Evaluation Service (March 2011)

Peoples, Columba and Nick Vaughan-Williams, Critical Security Studies: An Introduction (Abingdon: Routledge, 2010)

Perry, Avi, “Solving Israel’s African Refugee Crisis”, Virginia Journal of International Law, Vol. 51, No. 1 (October 2010)

Riajman, Rebeca and Adriana Kemp, “Labor Migration, Managing the Ethno-National Conflict, and Client Politics in Israel”, in Sarah S. Willen (ed.), Transnational Migration to Israel in Global Comparative Context (Plymouth: Lexington Books, 2007)

Sharma, Nandita, “Anti-Trafficking Rhetoric and the Making of a Global Apartheid”, NWSA Journal, Vol. 17, No. 3, States of Insecurity and the Gendered Politics of Fear (Autumn 2005)

Sofer, Arnon (ed.), Refugees or Work Immigrants from African Countries (Hebrew) (Haifa: National Security College Research Center and the Haikin Chair for Geostrategic Studies at the University of Haifa, December 2009)

Sofer, Arnon, Recommendations of the taskforce for stopping infiltrations to Israel and removing those who are staying in Israel illegally (in Hebrew), 4 November 2012

Williams, Jill, “Protection as subjection: Discourses of vulnerability and protection in post-9/11 border enforcement efforts”, City, Vol. 15, Nos. 3–4 (June–August 2011)

Yacobi, Haim, “‘Let Me Go to the City’: African Asylum Seekers, Racialization and the Politics of Space in Israel “, Journal of Refugee Studies Vol. 24, No. 1 (2010)

Yiftachel, Oren, Ethnocracy: Land and identity Politics in Israel/Palestine (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006)

Ziegler, Reuven (Ruvi), “The New Amendment to the ‘Prevention of Infiltration’ Act: Defining Asylum-Seekers as Criminals”, Israeli Democracy Institute Website, 16 January 2013, available at http://en.idi.org.il/analysis/articles/the-new-amendment-to-the-prevention-of-infiltration-act-defining-asylum-seekers-as-criminals/ (accessed 23/3/2013)

Government and NGO Publications

Association for the Civil Rights in Israel, “High Court of Justice to State: Explain legality of anti-infiltration law”, ACRI Website, 12 March 2013, available in http://www.acri.org.il/en/2013/03/12/infiltration-law-hearing/ (accessed 7/4/2013)

Human Rights Watch, Service for Life: State Repression and Indefinite Conscription in Eritrea, 16 April 2009, available in http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/eritrea0409web_0.pdf (accessed 3/4/2013)

Human Rights Watch, Sinai Perils: Risks to Migrants, Refugees, and Asylum Seekers in Egypt and Israel, 12 November 2008, available at http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/egypt1108webwcover.pdf (accessed 3/4/2013)

Mesila Annual Report 2011 (Hebrew), available in http://www.tel-aviv.gov.il/Tolive/welfare/Documents/%D7%93%D7%95%D7%97%20%D7%9E%D7%A1%D7%99%D7%9C%D7%94%20%D7%9C%D7%A9%D7%A0%D7%AA%202011.PDF (accessed 4/4/2013)

Population, Immigration and Border Crossings Administration (PIBA), Data regarding Foreigners in Israel, March 2013 (Hebrew), available in http://www.piba.gov.il/PublicationAndTender/ForeignWorkersStat/Documents/foreign_stat_032013.pdf (accessed 8/4/2013)

Redecker Hepner, Tricia, “An Open Letter to Israel: Eritreans are NOT Economic Refugees”, Asmarino Independent, 4 June 2012, available in http://asmarino.com/articles/1431-an-open-letter-to-israel-eritreans-are-not-economic-refugees (accessed 3/4/2013)

UN Official Documents

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “Revised Note on the Applicability of Article 1D of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees to Palestinian Refugees”, UNHCR website, available at http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/4add77d42.html (accessed 22/3/2013)

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Country Profile on Eritrea, available at http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/page?page=49e4838e6# (accessed 3/4/2013)

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, States Parties to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol, available at http://www.unhcr.org/protect/PROTECTION/3b73b0d63.pdf (accessed 6/4/2013)

News Articles

Bradley, Matt and Joshua Mitnick, “Bedouin Arms Smugglers See Opening in Sinai”, Wall Street Journal, 5 February 2011, available in http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704570104576124363132383924.html (accessed 14/4/2013)

Cohen, Tamir, “African migrants unwittingly funding Hamas terrorists, investigators say”, Haaretz, 24 July 2012, available in http://www.haaretz.com/news/diplomacy-defense/african-migrants-unwittingly-funding-hamas-terrorists-investigators-say-1.453144 (accessed 6/4/2013)

Greenwood, Phoebe, “Israeli anti-immigration riots hit African neighbourhood of Tel Aviv”, The Telegraph, 24 May 2012, available in http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/israel/9287715/Israeli-anti-immigration-riots-hit-African-neighbourhood-of-Tel-Aviv.html (accessed 14/4/2013)

Hartman, Ben, “5 Israelis arrested for attacking Africans in TA”, The Jerusalem Post, 10 April 2013, available in http://www.jpost.com/NationalNews/Article.aspx?id=309335 (accessed 14/4/2013)

Hartman, Ben, “Number of ‘infiltrators’ drops drastically”, The Jerusalem Post, 4 March 2013, available in http://www.jpost.com/National-News/Number-of-infiltrators-drops-drastically-308536 (accessed 7/4/2013)

Heller, Jeffrey and Dan Williams, “Israel completes bulk of Egypt border fence”, Reuters, 2 January 2013, available in http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/01/02/us-israel-egypt-fence-idUSBRE9010EI20130102 (accessed 8/4/2013)

Hoffman, Gil, “Miri Regev apologizes for calling migrants ‘cancer'”, The Jerusalem Post, 27 May 2012, available in http://www.jpost.com/DiplomacyAndPolitics/Article.aspx?id=271616&R=R9 (accessed 6/4/2013)

Mitnick, Joshua, “Israel Finishes Most of Fence on Sinai Border”, The Wall Street Journal, 2 January 2013, available in http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324374004578217720772159626.html (accessed 8/4/2013)

Nesher, Talila, “Attorney General orders a halt to Israel’s deportation of Eritrean migrants”, Haaretz, 5 March 2013, available in http://www.haaretz.com/news/national/attorney-general-orders-a-halt-to-israel-s-deportation-of-eritrean-migrants-1.507262 (accessed 7/4/2013)

Nesher, Talila, “Israel secretly repatriated 1,000 to Sudan, without informing UN”, Haaretz, 26 February 2013, available in http://www.haaretz.com/news/diplomacy-defense/israel-secretly-repatriated-1-000-to-sudan-without-informing-un.premium-1.505806 (accessed 7/4/2013)

Novik, Akiva, “Yishay’s ‘Doomsday Weapon’: Watch Shas’ abandoned campaign” (Hebrew), Ynet, 31 December 2012, available in http://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,l-4326501,00.html (accessed 6/4/2013)

Weiler-Polak, Dana and Tomer Zarchin, “Israel begins deportation of South Sudanese migrants”, Haaretz, 10 June 2012, available in http://www.haaretz.com/news/national/israel-begins-deportation-of-south-sudanese-migrants-1.435523 (accessed 7/4/2013)

Weiss, Dana, “Eli Yisahy: Foreign workers will bring a disaster” (Hebrew), Channel 2 News Israel, 31 October 2009, available in http://reshet.tv/%D7%97%D7%93%D7%A9%D7%95%D7%AA/News/Politics/Politics/Article,30299.aspx (accessed 6/4/2013)

Zeiger, Asher, “Police arrest Eritrean migrant in connection with rape of elderly woman”, The Times of Israel, 31 December 2012, available in http://www.timesofisrael.com/police-arrest-eritrean-migrant-in-conncetion-with-rape-of-elderly-woman/ (accessed 6/4/2013)

Domestic Legislation and International Legal Conventions

Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (1951), available at http://www.unhcr.org/3b66c2aa10.html (accessed 22/3/2013)

Prevention of Infiltration (Offences and Jurisdiction) Law, 5714-1954, approved English translation available at http://www.israellawresourcecenter.org/emergencyregs/fulltext/preventioninfiltrationlaw.htm (accessed 23/3/2013)

Prevention of Infiltration Law (Amendment No. 3 and its provisions, 2011 (Hebrew), available in http://www.justice.gov.il/NR/rdonlyres/A4F2702C-837B-482D-BCC0-9B718CFEF150/32992/2332.pdf (accessed 23/3/2013)

Websites

Freedom House: http://www.freedomhouse.org

[1] Roxanne Lynn Doty, “The Double-Writing of Statecraft: Exploring State Responses to Illegal Immigration”, Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, Vol. 21, No. 2 (April-June 1996), p. 172-175

[2] Note that Israel has categorically refused to recognise the rights of Palestinian refugees to seek asylum in Israel under the 1951 UN Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (hereinafter ‘1951 Convention’), following a strict interpretation of certain clauses;cf. UNHCR, “Revised Note on the Applicability of Article 1D of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees to Palestinian Refugees”, UNHCR website, available at http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/4add77d42.html (accessed 22/3/2013)

[3] For a legal definition of a ‘refugee’ see the 1951 convention, Article 1A(2); Asylum seekers are “people who have moved across international borders in search of protection under the 1951 Refugee Convention, but whose claim for refugee status has not yet been determined”, quoted in Avi Perry, “Solving Israel’s African Refugee Crisis”, Virginia Journal of International Law, Vol. 51, No. 1 (October 2010), p. 159

[4] Reece Jones, “Border security, 9/11 and the enclosure of civilisation”, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 177, No. 3 (September 2011), p. 214

[5] Roxanne Lynn Doty, “Desert Tracts: Statecraft in Remote Places”, Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, Vol. 26, No. 4, Race in International Relations (October-December, 2001), pp. 526-527; Tally Kritzman-Amir, “”Otherness” as the Underlying Principle in Israel’s Asylum Regime”, Israel Law Review, Vol. 42, No. 3 (January 2009), pp. 606-607; David Campbell, Writing Security: United States Foreign Policy and the Politics of Identity, Revised Edition (Manchester, UK: University of Manchester Press, 1998), p. 23

[6] Jones, p. 214

[7] David Newman, “The lines that continue to separate us: borders in our ‘borderless’ world”, Progress in Human Geography, Vol. 30, No. 2 (2006), p. 147, emphasis added

[8] Columba Peoples and Nick Vaughan-Williams, Critical Security Studies: An Introduction (Abingdon: Routledge, 2010) hereinafter CSS, pp. 140-142

[9] CSS, p. 143; Campbell, pp. 9, 80-81

[10] Doty, “The Double-Writing of Statecraft”, pp. 179-181

[11] Columba Peoples and Nick Vaughan-Williams, Critical Security Studies: An Introduction (Abingdon: Routledge, 2010) hereinafter CSS, pp. 142-143

[12] CSS, p. 139

[13] CSS, pp. 145-146

[14] Kritzman-Amir, pp. 606-607

[15] Carrie Dawson, “On Thinking Like a State and Reading (about) Refugees”, Journal of Canadian Studies, Vol.

45, No. 2 (Spring 2011), p. 70

[16] Nandita Sharma, “Anti-Trafficking Rhetoric and the Making of a Global Apartheid “, NWSA Journal, Vol. 17, No. 3, States of Insecurity and the Gendered Politics of Fear (Autumn 2005), pp. 89-90

[17] Zrinka Bralo and John Morrison, “Immigrants, Refugees and Racism: Europeans and Their Denial”, in Elspeth Guild and Joanne van Selm (eds.), International Migration and Security: Opportunities and Challenges (Abingdon: Routledge, 2005), p. 113

[18] Roxanne Lynn Doty, “Immigration and the politics of security”, Security Studies, Vol. 8, Nos. 2-3 (1998), pp. 74-80

[19] CSS, p. 137

[20]Jef Huysmans, “Minding Exceptions: The Politics of Insecurity and Liberal Democracy”, Contemporary Political Theory, Vol. 3 (2004), p. x

[21] Doty, “The Double-Writing of Statecraft”, p. 183; Campbell, pp. 75-86

[22] Huysmans, pp. 322-336

[23] Oren Yiftachel, Ethnocracy: Land and identity Politics in Israel/Palestine (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), p. 11

[24] Yiftachel, pp. 11-15

[25] Yiftachel, pp. 35-37

[26] Rebeca Riajman and Adriana Kemp, “Labor Migration, Managing the Ethno-National Conflict, and Client Politics in Israel”, in Sarah S. Willen (ed.), Transnational Migration to Israel in Global Comparative Context (Plymouth: Lexington Books, 2007), pp. 33-47; Karin Fathimath Afeef, “A promised land for refugees? Asylum and migration in Israel”, New Issues in Refugee Research, Research Paper No. 183, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Policy Development and Evaluation Service (December 2009), p. 4

[27] Daphna Canetti-Nisim and Ami Pedahzur, “Contributory factors to Political Xenophobia in a multi-cultural society: the case of Israel”, International Journal of Intercultural Relations, Vol. 27 (2003), pp. 310-311

[28] Canetti-Nisim and Pedahzur, p. 327

[29] Afeef, p. 6; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, States Parties to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol, available at http://www.unhcr.org/protect/PROTECTION/3b73b0d63.pdf (accessed 6/4/2013)

[30] Jonathan Paz, “Ordered disorder: African asylum-seekers in Israel and discursive challenges to

an emerging refugee regime”, New Issues in Refugee Research, Research Paper No. 205, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Policy Development and Evaluation Service (March 2011), p. 4; Anat Ben-Dor, “Refugees and Asylum-seekers – Unwelcomed Guests in the State of Israel: Information Page” (in Hebrew), Tel Aviv University Legal Clinics, available at http://www.law.tau.ac.il/Heb/?CategoryID=499&ArticleID=723 (accessed 21/3/2013)

[31] Paz, pp. 2-4; Afeef, p. 8-9, 21

[32] Afeef, pp. 8-10

[33] Human Rights Watch, Sinai Perils: Risks to Migrants, Refugees, and Asylum Seekers in Egypt and Israel, 12 November 2008, available at http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/egypt1108webwcover.pdf (accessed 3/4/2013), pp. 19-20

[34] Tricia Redecker Hepner, “An Open Letter to Israel: Eritreans are NOT Economic Refugees”, Asmarino Independent, 4 June 2012, available in http://asmarino.com/articles/1431-an-open-letter-to-israel-eritreans-are-not-economic-refugees (accessed 3/4/2013); Human Rights Watch, Service for Life: State Repression and Indefinite Conscription in Eritrea, 16 April 2009, available in http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/eritrea0409web_0.pdf (accessed 3/4/2013); for official data see UNHCR Country Profile on Eritrea, available at http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/page?page=49e4838e6# (accessed 3/4/2013)

[35] Afeef, pp. 8-10

[36]Afeef, p. 10;Paz, pp. 2-4

[37] The difference in characteristics of the labour migrant and asylum communities is clearly demonstrated in the Tel-Aviv Municipality’s Mesila Annual Report 2011 (Hebrew), available in http://www.tel-aviv.gov.il/Tolive/welfare/Documents/%D7%93%D7%95%D7%97%20%D7%9E%D7%A1%D7%99%D7%9C%D7%94%20%D7%9C%D7%A9%D7%A0%D7%AA%202011.PDF (accessed 4/4/2013), pp. 3-9

[38] Population, Immigration and Border Crossings Administration (PIBA), Data regarding Foreigners in Israel, March 2013 (Hebrew), available in http://www.piba.gov.il/PublicationAndTender/ForeignWorkersStat/Documents/foreign_stat_032013.pdf (accessed 8/4/2013); the data also suggests that over 9000 migrants have entered Israel illegally and have already left the country, either voluntarily or by deportation.

[39] Human Rights Watch, Sinai Perils, p. 37; Matt Bradley and Joshua Mitnick, “Bedouin Arms Smugglers See Opening in Sinai”, Wall Street Journal, 5 February 2011, available in http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704570104576124363132383924.html (accessed 14/4/2013); Paz, pp. 2-3

[40] For a comparison see Freedom House profiles on both Israel and the West Bank and Gaza in http://www.freedomhouse.org/country/israel; http://www.freedomhouse.org/country/west-bank-and-gaza-strip

[41] Kritzman-Amir, p. 608

[42] Kritzman-Amir, pp. 605-606

[43] Administrative Appeal 1644/05, Frieda v. Ministry of the Interior, Supreme Court Cases 2005(2), 4269, quoted in Shlomo Avineri, Liav Orgad and Amnon Rubinstein, Managing Global Migration: A Strategy for Immigration Policy in Israel, The Metzilah Center for Zionist, Jewish, Liberal and Humanist Thought Position Paper (2010), available at http://www.metzilah.org.il/webfiles/fck/file/Immi_Book%20final.pdf (accessed 4/4/2013), pp. 29-30

[44] ; Avineri et al, p. 31Haim Yacobi, “‘Let Me Go to the City’: African Asylum Seekers, Racialization and the Politics of Space in Israel “, Journal of Refugee Studies Vol. 24, No. 1 (2010), pp. 63-64

[45] For a detailed analysis of Israel’s ethnocratic regime see Yiftachel, pp. 84-130

[46] Yacobi, p. 48

[47] Paz, pp. 10-12

[48] Yacobi, pp. 49-50

[49] Kritzman-Amir, pp. 620-621

[50] Human Rights Watch, Sinai Perils, pp. 21-24

[51] Kritzman-Amir, p. 623

[52] Perry, p. 175; Gilad Natan, “Treatment of Infiltrators from the Egyptian Border” (Hebrew), Knesset Research and Information Center, 26 May 2010, p. 4

[53] Paz, p. 6

[54] Paz, p. 7; Avineri et al, p. 57; Kritzman-Amir, pp. 617-619

[55] Afeef, p. 10

[56] Paz, pp. 2-4; Afeef, p. 8-9, 21

[57] The strategy of redirecting smuggling routes to perilous locations in the frontier area is widely known. For more examples see Jill Williams, “Protection as subjection: Discourses of vulnerability and protection in post-9/11 border enforcement efforts”, City, Vol. 15, Nos. 3–4 (June–August 2011), p. 417; Doty, “Desert Tracts”, p. 533-534

[58] Joshua Mitnick, “Israel Finishes Most of Fence on Sinai Border”, The Wall Street Journal, 2 January 2013, available in http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324374004578217720772159626.html (accessed 8/4/2013); Jeffrey Heller and Dan Williams, “Israel completes bulk of Egypt border fence”, Reuters, 2 January 2013, available in http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/01/02/us-israel-egypt-fence-idUSBRE9010EI20130102 (accessed 8/4/2013); Ben Hartman, “Number of ‘infiltrators’ drops drastically”, The Jerusalem Post, 4 March 2013, available in http://www.jpost.com/National-News/Number-of-infiltrators-drops-drastically-308536 (accessed 7/4/2013)

[59] Data adapted from PIBA, Data regarding Foreigners in Israel, March 2013

[60] Dana Weiler-Polak and Tomer Zarchin, “Israel begins deportation of South Sudanese migrants”, Haaretz, 10 June 2012, available in http://www.haaretz.com/news/national/israel-begins-deportation-of-south-sudanese-migrants-1.435523 (accessed 7/4/2013)

[61] Talila Nesher, “Attorney General orders a halt to Israel’s deportation of Eritrean migrants”, Haaretz, 5 March 2013, available in http://www.haaretz.com/news/national/attorney-general-orders-a-halt-to-israel-s-deportation-of-eritrean-migrants-1.507262 (accessed 7/4/2013); cf. Talila Nesher, “Israel secretly repatriated 1,000 to Sudan, without informing UN”, Haaretz, 26 February 2013, available in http://www.haaretz.com/news/diplomacy-defense/israel-secretly-repatriated-1-000-to-sudan-without-informing-un.premium-1.505806 (accessed 7/4/2013)

[62] Prevention of Infiltration (Offences and Jurisdiction) Law, 5714-1954, English translation available at http://www.israellawresourcecenter.org/emergencyregs/fulltext/preventioninfiltrationlaw.htm (accessed 23/3/2013); Prevention of Infiltration Law (Amendment No. 3 and its provisions, 2011 (Hebrew), available in http://www.justice.gov.il/NR/rdonlyres/A4F2702C-837B-482D-BCC0-9B718CFEF150/32992/2332.pdf (accessed 23/3/2013); Reuven (Ruvi) Ziegler, “The New Amendment to the ‘Prevention of Infiltration’ Act: Defining Asylum-Seekers as Criminals”, Israeli Democracy Institute Website, 16 January 2013, available at http://en.idi.org.il/analysis/articles/the-new-amendment-to-the-prevention-of-infiltration-act-defining-asylum-seekers-as-criminals/ (accessed 23/3/2013); Bruno Oliveira Martins, Undocumented Migrants, Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Israel, EuroMeSCo Paper No. 81 (February 2009), p. 16

[63] Association for the Civil Rights in Israel, “High Court of Justice to State: Explain legality of anti-infiltration law”, ACRI Website, 12 March 2013, available in http://www.acri.org.il/en/2013/03/12/infiltration-law-hearing/ (accessed 7/4/2013)

[64] Gil Hoffman, “Miri Regev apologizes for calling migrants ‘cancer'”, The Jerusalem Post, 27 May 2012, available in http://www.jpost.com/DiplomacyAndPolitics/Article.aspx?id=271616&R=R9 (accessed 6/4/2013)

[65] Arnon Sofer, Recommendations of the taskforce for stopping infiltrations to Israel and removing those who are staying in Israel illegally (in Hebrew), 4 November 2012, hereinafter “Sofer Report”, pp. 10-29; also see Arnon Sofer (ed.), Refugees or Work Immigrants from African Countries (Hebrew) (Haifa: National Security College Research Center and the Haikin Chair for Geostrategic Studies at the University of Haifa, December 2009)

[66] Dana Weiss, “Eli Yisahy: Foreign workers will bring a disaster” (Hebrew), Channel 2 News Israel, 31 October 2009, available in http://reshet.tv/%D7%97%D7%93%D7%A9%D7%95%D7%AA/News/Politics/Politics/Article,30299.aspx (accessed 6/4/2013); Yacobi, pp. 60-62; cf. Zohar Mor, Itamar Groto and Alex Leventhal, “Tuberculosis and AIDS in Immigrants – is that so?” (Hebrew), The Medicine (Ha’REfua), Vol. 151, No. 3 (March 2012), pp. 175-177

[67] Akiva Novik, “Yishay’s ‘Doomsday Weapon’: Watch Shas’ abandoned campaign” (Hebrew), Ynet, 31 December 2012, available in http://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,l-4326501,00.html (accessed 6/4/2013)

[68] Tamir Cohen, “African migrants unwittingly funding Hamas terrorists, investigators say”, Haaretz, 24 July 2012, available in http://www.haaretz.com/news/diplomacy-defense/african-migrants-unwittingly-funding-hamas-terrorists-investigators-say-1.453144 (accessed 6/4/2013); Asher Zeiger, “Police arrest Eritrean migrant in connection with rape of elderly woman”, The Times of Israel, 31 December 2012, available in http://www.timesofisrael.com/police-arrest-eritrean-migrant-in-conncetion-with-rape-of-elderly-woman/ (accessed 6/4/2013)

[69] Phoebe Greenwood, “Israeli anti-immigration riots hit African neighbourhood of Tel Aviv”, The Telegraph, 24 May 2012, available in http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/israel/9287715/Israeli-anti-immigration-riots-hit-African-neighbourhood-of-Tel-Aviv.html (accessed 14/4/2013); Ben Hartman, “5 Israelis arrested for attacking Africans in TA”, The Jerusalem Post, 10 April 2013, available in http://www.jpost.com/NationalNews/Article.aspx?id=309335 (accessed 14/4/2013)

[70] Martins, pp. 13-14

[71] Afeef, pp. 13-14; Paz, pp. 12-14

[72] Doty, “The Double-Writing of Statecraft”, pp. 177-178

[73] Paz, p. 8-10

[74] Primo Levi (trans. Stuart Woolf), “Author’s Preface”, If This is a Man and The Truce (London: Abacus, 1987), p. 15

[75] See examples of such practices worldwide in: Alice Bloch and Liza Schuster, “At the extremes of exclusion: Deportation, detention and dispersal”, Ethnic and Racial Studies, Vol. 28, No. 3 (May 2005), pp. 491-512; David Farrier, “Everyday Exceptions: The Politics of the Quotidian in Asylum Monologues and Asylum Dialogues”, Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies, Vol. 14, No. 3 (2012), p. 432; Rutvica Andrijasevic, “From Exception to Excess: Detention and Deportations across the Mediterranean Space”, in Nicholas de Genova and Nathalie Peutz (eds.), The Deportation Regime: Sovereignty, Space, and the Freedom of Movement (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), pp. 147-165; Doty, “Immigration and the politics of security”, p. 87; Tally Kritzman-Amir and Yonatan Berman, “Responsibility Sharing and the Rights of Refugees: The Case of Israel”, The George Washington International Law Review, Vol. 41, No. 3 (October 2010), p. 623; Bralo and Morrison, p. 113; Paz, p. 3; Joanne van Selm, “Immigration and Regional Security”, in Guild and van Selm, pp. 20-24; Elspeth Guild, “Cultural and Identity Security: Immigrants and the Legal Expression of National Identity”, in Guild and van Selm, pp. 104-105; Sharma, pp. 92-93; Perry, pp. 166-168; Jones, pp. 213-216

[76] Sofer Report, pp. 7-9; Avineri et al, pp. 25-29, 37

[77] Perry, p. 169

[78] Avineri et al, pp. 27-29

[79] Avineri et al, pp. 33-34, 63-70

—

Written by: Eliran Kirschenbaum

Written at: The University of Manchester

Written for: Dr. Cristina Masters

Date written: April-May 2012

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Bargaining for Protection – the Case of Climate Refugees

- Are ‘Climate Refugees’ Compatible with the 1951 Refugee Convention?

- Understanding Refugees Through ‘Home’ by Warsan Shire

- A Well-Founded Fear of Environment: International Resistance to Climate Refugees

- National Identity and the Construction of Enemies: Constructivism and Populism

- Deterrence and Ambiguity: Motivations behind Israel’s Nuclear Strategy