Voters in the Czech Republic went to the polls in early legislative elections on 25-26 October. The elections followed the collapse in June, amid personal and political scandal, of the minority centre-right government of Petr Nečas and the subsequent failure of a technocrat administration imposed by President Miloš Zeman to win a parliamentary vote of confidence.

As in the previous May 2010 elections, the result saw losses for established parties and breakthroughs by new anti-establishment groupings campaigning on platforms of fighting corruption, renewing politics and making government work better. However, the 2013 results represent a decisive breach in the Czech Republic’s previously stable pattern of party politics party whose four main pillars – pro-market conservatives, Social Democrats, Christian Democrats and Communists – made it arguably Central and Eastern Europe’s best approximation to a West European style party system. The new political landscape that has emerged is both fluid and highly fragmented, with no fewer than seven parties now represented in the Chamber of Deputies.

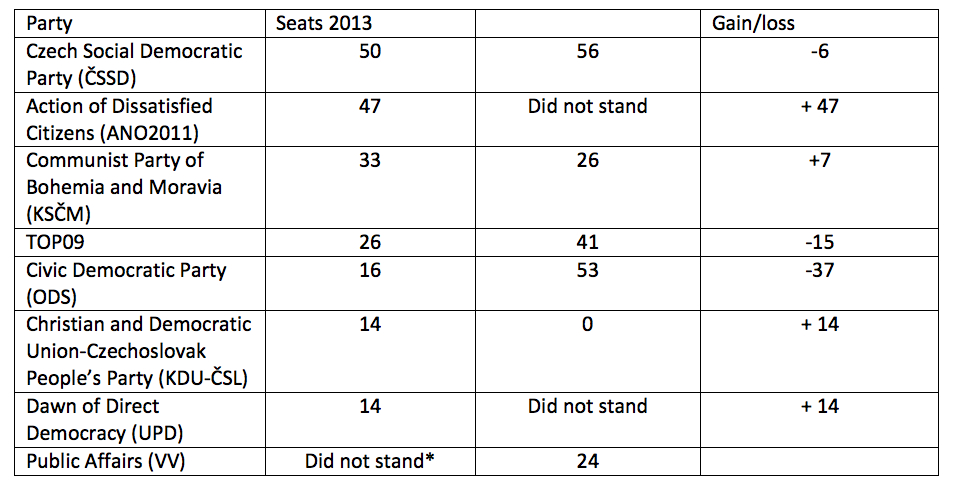

Seats held by parties following Czech parliamentary elections of 25-26 October. Source: Czech Statistical Office (www.volby.cz). *Four deputies elected for UPD were members of VV.

The biggest losers in the election were parties of the Czech centre-right: the Civic Democrats (ODS) formerly led by Nečas and TOP09, the party led by the Czech Republic’s aristocratic former foreign minister Karel Schwarzenberg. The once dominant ODS founded in 1991 by Václav Klaus to bring British-style Thatcherite free market conservatism to Czech lands was cut down to a mere 7 per cent of the vote. As a party less implicated in the engrained corruption that had damaged ODS electorally, TOP09 fared better slipping from 16 per cent to just under 12 per cent support. However, the party failed to repeat its success in January’s presidential elections when Schwarzenberg’s candidacy successively united a broad coalition of liberal and centre-right voters against the left-wing challenge of Miloš Zeman. The Christian Democrats (KDU-ČSL) who had dropped out of parliament in 2010 – staged a modest recovery returning to the Chamber of Deputies with 6 per cent support. ‘Heads Up!’ the conservative eurosceptic bloc endorsed by Václav Klaus, polled a humiliating 0.42 per cent.

However, the result was also deeply disappointing for the main opposition party, the Czech Social Democrats (ČSSD) who had been consistently predicted by opinion polls in the months before the election to emerge as clear winners. Despite ‘winning’ the election, ČSSD’s 20.45 per cent represented a 2 per cent decline in its support and was its lowest share in the history of the independent Czech Republic. As well as falling far short of the party’s 25 per cent minimum target vote, 2013 was the second successive election fought in opposition in which the Social Democrats’ vote has declined.

Although the hardline Czech Communists (KSČM) increased their vote to just under 15 per cent, the major winners of the election were arguably the two new anti-establishment parties that broke into parliament: Dawn of Direct Democracy (UPD), which polled 6.88 per cent, and the Action of Dissatisfied Citizens (ANO2011) movement of the agro-food billionaire Andrej Babiš. ANO2011’s 18.65 per cent share of the vote – the highest vote for any new party in the 20 year history of the Czech Republic – propelled it from a extra-parliamentary obscurity into second place.

‘Centrist Populism’

Both new parties are essentially populist creations which make what the Slovak political scientist Peter Účen terms a ‘centrist populist’ appeal lambasting established elites as corrupt and ineffective and promising to remake the political system. Their stances on economic and cultural issues are devoid of the ideological radicalism of far-right or far-left populism.

Dawn of Direct Democracy is led by the Czech-Japanese businessman Tomio Okamura, who first came to prominence as a judge on the Czech TV’s version of Dragon’s Den in 2010, and later won a seat in the Czech Senate as an independent. Although not above baiting the Roma minority – using his unusual Czecho-Japanese background to deny accusations of racism –Okamura’s main focus was to attack the political class and to demand the introduction of binding national referenda (supposedly) on the Swiss model.

ANO2011, which spells out the Czech word ‘yes’ (ano) in acronym, was founded by the Slovak-born billionaire Andrej Babiš following a high profile press interview in September 2011 in which claimed that levels of corruption had reached unsustainable level. Initially characterised by a vague rhetoric of anti-corruption and political reform, the movement evolved into an organised, well-funded group with a slate of candidates recruited from business and public administration and a clear programme, partly borrowed from NGOs, on creating a cleaner, more effective ‘reconstructed state’ capable of delivering better and cheaper public goods. Babiš himself projected himself as a hard-working non-political businessman who has finally had enough of corruption and would turn round the country by running it like a successful enterprise

ANO2011 also made calibrated appeals on other issues, targeting disillusioned right-wing voters while also putting forwards some policies calculated to voters on the left such as cuts in VAT on basic consumer items and the scrapping of ‘hotel’ charges in hospitals and compulsory property declarations for politicians and officials. Election-day polling, however, suggests that ANO2011 voters, who were distributed relatively across regions, income and age grounds, were more motivated by a desire for change than support for any of the movement’s specific commitments. Voters also seem to have been unfazed by evidence that Babiš collaborated with the communist-era secret police during 1980s when working an executive for state petrochemicals trading company – a claim he denies.

A Government Quandary

The success of Babiš’s movement places all established parties in a political quandary. Not only has the movement’s appeals been effective in winning over an electorate frustrated by austerity and perceived corruption, its success also makes it indispensible to forming the next government. The Social Democrats’ plans for a government of the left backed by a pact (but not a coalition) with the Communists fell by the wayside. Together the two parties command a mere 83 seats in the 200 member Chamber. On the centre-right ANO2011 could form a minimum winning coalition with the three traditional parties of the Czech right. However, Andrej Babiš was adamant that his movement will not work in a government with parties he sees as symbolising two decades of corruption. The politically feasible combination capable of generating a parliamentary majority would thus be a three-way agreement between ANO2011, the Social Democrats and the Christian Democrats – a traditional ‘pivotal party’ in Czech coalition-making.

A Challenge to Democratic Party Government

Despite differences on issues such as tax and the restitution of Church property, the basis of deal between the three parties does exist. It is unclear, however, whether ANO2011 will enter a formal coalition (as the Social Democrats wish) or agree only to minority Social Democrat-Christian Democrat administration as an external support party (ANO2011’s preferred option).

In either case, the movement’s rapid arrival in – or close to – the heart of government poses questions about the future of party government in the Czech Republic, which has already been shaken by President Zeman’s expansive use of his own power and disregard for constitutional conventions.

There are three principal distorting effects that the arrival of Babiš and ANO2011 may have on the possibilities for democratic party government in the Czech Republic.

First, the rise of a super-rich businessman turned anti-politician leading a top-down movement which bears all the organisational hallmarks of what Hopkin and Paolucci term the ‘business-firm’ party, has prompted inevitable concerns that Babiš is a ‘Czech Berlusconi’ whose commercial interests will distort public policy far more than the corrupt, but diffuse, interventions of informal lobbies and interest groups that have so far characterised policy-making. Although his Agrofert conglomerate operates mainly in agriculture, food and chemicals sectors, Babiš has done little to dispel such fears by buying strategically into the Czech media, most recently taking over as publisher of two of the Czech Republic’s main newspapers, and declaring that he planned to continue running his businesses if elected to parliament.

Pressure is currently building for ANO2011 to enter government to make it directly accountable to the electorate rather than able it to exercise leverage from the parliamentary sidelines. Some analysts have even suggested (for the same reason) that Babiš should become prime minister. This is unlikely to happen. Although the ANO2011 leader says he would consider the post of finance minister, enforcement of the Czech Republic’s anti-communist lustration (screening) procedures may bar him from the cabinet because of his apparent secret police links. Moreover, Babiš’s hastily created movement lacks experienced personnel and, it if does nominate ministers is likely to look outside its own ranks to technocrats and independents, further diluting any sense of responsible party government.

Some have argued that in some circumstances populist breakthroughs can act as a democratic corrective, breaking down an ossified party establishment and allowing new voices to enter political system. The emergence of anti-corruption parties such as ANO2011 is to some extent a response to public demand and the greater salience of anti-corruption as an issue in post-communist Central Europe. However, the 59 year-old Babiš is an unlikely reformist outsider. The son of a Communist foreign trade official and himself a Communist Party member before 1989, he built up the Agrofert conglomerate after the fall of communism, in part, by striking deals with governments dominated by the parties he now condemns.

Second, earlier experience suggests that the anti-corruption parties and reformist ‘centrist populists’ proliferating across Central and Eastern Europe can sometimes be vehicles for the very vested interests they are supposedly opposing. This was, for example, certainly the case with the Public Affairs (VV) party which, like ANO2011, emerged from marginality to poll 10 per cent of the vote in 2010 promising to take on the ‘political dinosaurs’ of the party establishment. VV’s façade of citizen-politicians, internet-based direct democracy and a new politics of transparency was, however, quickly tarnished when it transpired that the party had been conceived and financed by the founder of the ABL security firm as a part of a strategy to gain political influence and secure municipal contracts in Prague.

Finally, even if Babiš and ANO2011 turn out to be committed reformers able to stem the deep conflicts of interest raised by the party’s origins, the potential instability of the movement poses problems for democratic governance. Like the founders of other new ‘flash’ parties Babiš may struggle to hold together a movement with no clear unifying ideology and a large inexperienced parliamentary group. The smaller Dawn of Direct Democracy is likely to face similar pressures. Such parties also lose their appeal as novel outsiders over time, particularly if they play a role in government, which may make them targets of same mix of anti-establishment protest voting and social frustration that propelled them to office.

Such fragility has consequences for party government. It risks opening up a cycle of weak minority administrations or awkward compromise governments agreed between established parties of left and right (Grand Coalitions, teams of technocratic caretakers) which in turn feeds voter demand for new anti-establishment protest parties. The emergence of ANO2011 and Dawn is a part of such a pattern following directly on success in the 2010 election and post-election implosion of Public Affairs, which left the Czech Republic without any viable majority government.

—

Seán Hanley is Senior Lecturer in East European Politics at University College London. His research focuses on the emergence of new anti-establishment parties in Europe. He also writes a personal academic blog on Czech and Central European politics.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The 2018 Elections and the Uncertain Future of Brazilian Democracy

- Away from Political Parties into Lifestyle Politics: Young People in Advanced Democracies

- Zimbabwe Elections: The Local and Regional Implications

- The 2024 Elections, Disinformation, Cyberattacks and the Possibility of Insurgency in the US

- Looking Back at 2011

- Hatred and Fear: Bolsonaro and the Return of Irrational Politics