‘Everybody Breaks Eventually’: Torture and the Impact of 24 on America After 9/11

Abstract

Since the terrorist attacks of September 11th 2001, the fictional representation of torture on US television has grown exponentially; not only is a higher volume of torture scenes shown but the context in which torture is administered has also changed. Now torture is a patriotic act carried out by the ‘good guys’ as an effective counterterrorism tool. The focus of this research is to investigate the impact this representation of torture has had on the attitudes and actions of the American public and military in the eleven years following 9/11. To discern the nature and impact of torture’s representation, a mixed qualitative and quantitative research approach is adopted, comprising three pieces of individual research. This includes a discourse analysis of popular counterterrorism thriller 24 (2001-2010), a statistical survey of American public opinion data on torture and its methods (2001-2012), and a documentary analysis of military autobiographies of soldiers and interrogators. Although no causal link can be established between the fictional ‘torture myth’ and individual beliefs and actions, this research takes seriously the influence of popular culture in demonstrating the spheres within which these factors converge. The research establishes that a consistent myth of torture is represented on 24, outlining the practice as physically effective and justified to fight terrorism. Over the same period, a long-term upward trend in the American public’s support for torture evidently started becoming the majority view in 2009. Individual soldier experiences reveal the situational context in which the torture myth became persuasive, further outlining instances when 24 or fictionalized torture directly impacted real-life decisions and actions. This research therefore concludes that the fictionalized representation of torture as effective, justified and patriotic has had an important impact on American attitudes and beliefs over time. Recommendations are made to establish causal links and extend the research so that cultural interpretation is taken seriously in future research in International Relations.

List of Tables

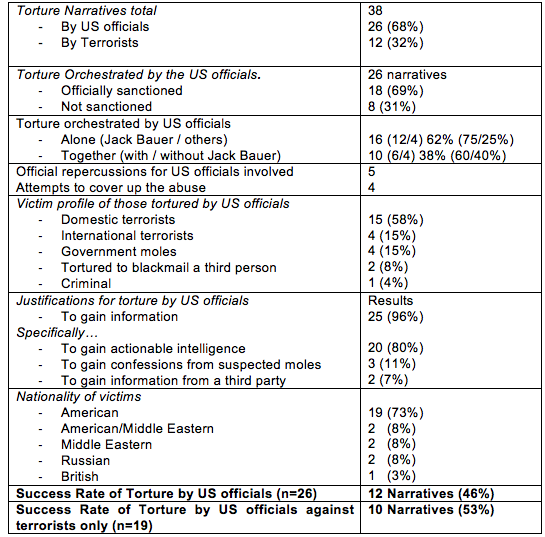

Table 1: Main Findings of the Discourse Analysis of Torture in 24 – Government Orchestrated Torture

Table 2: Main Findings of the Discourse Analysis of Torture in 24 – Terrorist orchestrated torture

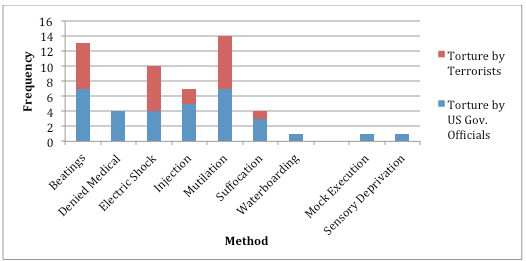

Table 3: Success Rates of US Orchestrated Torture

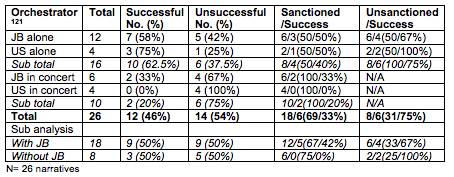

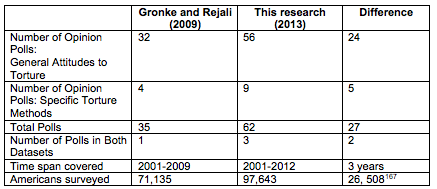

Table 4: Comparison of Datasets

Table 5: Average Support and Opposition to Torture

Table 6: 24 and American Public Opinion

List of Charts

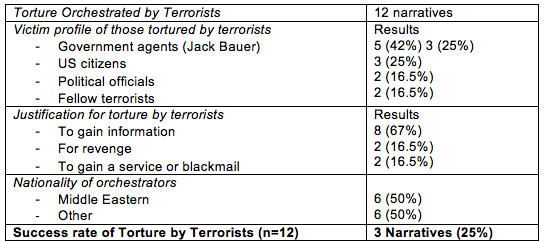

Chart 1: Methods of Torture on 24

Chart 2: Overall Results of American Public Opinion Survey

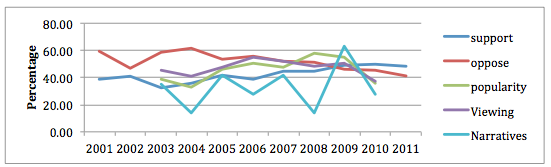

Chart 3: Public Opinion, Torture Narratives and Viewing Popularity of 24

CHAPTER 1 – Introduction

Background and Research Focus

“You are going to tell me what I want to know – it’s just a matter of how much you want it to hurt”, Jack Bauer tells one of his captives in the pursuit of actionable intelligence in the popular TV series 24.[1] Immediately after the 9/11 attacks in 2001, 60% of the American public opposed the use of interrogational torture as a mechanism for counterterrorism.[2] A decade later this trend has reversed with the majority of American’s now supporting the use of torture on terrorism suspects to gain information. This thesis seeks to explain why torture has become more and not less acceptable to the American people over the course of its Global War on Terror.[3]

In pursuit of actionable intelligence during the Administrations of George W. Bush, state-sponsored policies of coercive interrogation techniques coupled with military culture and lack of interrogational supervision on the ground resulted in the widespread mistreatment of detainees in United States (US) custody. The role played by American popular culture, especially television, is underdeveloped in understanding its influence in shaping societal beliefs about the effectiveness and necessity of interrogational torture as a strategy of counterterrorism.

Overall Research Aim and Research Objectives

This research aims to investigate how torture has been represented on US television and to establish the impact of this representation on the attitudes and beliefs of military practitioners and the US public. As a proxy for the new brand of ‘spytainment’, a critical review of 24 (2001-2010) is used to establish the nature of televised torture.[4] This representation will then be ‘mapped’ onto existing accounts of military practitioner action and US public opinion to assess degrees of convergence. First aired in October 2001, 24 came to epitomize America’s fight against terrorism in the ensuing decade and is the ‘de facto’ television programme of the War on Terror. It encouraged Guantanamo interrogators to see themselves as on the “front line” and “go further than they might otherwise have”.[5]

This research has the following objectives:

- To identify how torture has been represented on 24 and presented to the American public.

- To evaluate critically domestic US public opinion on the applicability and effectiveness of torture and coercive techniques during the post-9/11 decade.

- To clarify the origins of detainee abuse and explore the impact of fictional interrogation on military practitioners under the Bush Administration.

- To formulate recommendations for future research.

Research Approach and Methodology

To satisfy the research objectives, a holistic and triangulated method is used to investigate the diverse visual, individual and societal spheres in which the issue of torture spans. Whilst direct causal links between the representation of torture on television and individual beliefs cannot be established, this research embodies both a qualitative and quantitative approach to best discern the instances under which torture in these separate spheres have overlapped. The research is primarily located in the qualitative canon, informed by post-positivist approaches to International Relations (IR) and is situated in the space between semiotics and post-structuralism. It is based on a literature review of existing research into television and US prisoner abuse and a discourse analysis of 24. Trends drawn out are enhanced by the quantitative survey of American public opinion over the decade following 9/11 in order to establish the extent to which these torture messages were internalized by society, rather than performed by a few ‘bad apples’, which is supplemented by documentary reading of available military autobiographies.[6] This is necessary, as televised torture cannot be fully expressed through a constructivist or positivist approach. A comprehensive societal view is required to establish the baseline of the impact of televised torture.

Approach and Method: Between Semiotics and Post Structuralism

The subjective interpretation of images and television does not sit comfortably within the empiricist and rationalist paradigms prominent in IR.[7] The analysis of 24 is premised on the research traditions established by semiology and post-structuralism. These are distinct from rationalist theories of IR in their ontological and epistemological aspirations through highlighting the underlying ideological and power relationships behind images and texts.

Semiotics, or the ‘study of signs’ explores the process whereby the meanings of images reflect power interests and perpetuates social inequalities. It focuses on the structure of the source and the immediate system of meaning within which it is embedded. [8] Roland Barthes was the first theorist to systematically apply semiotic theory to popular culture. [9] Expanding on the work of Ferdinand de Saussure, Bathes argued that a secondary level of connotation exists where additional ideas and values are communicated beyond how they are physically represented.[10] This he refers to as a myth: “an ideology that defends prevailing structures of power by actively promoting the values and interests of dominant groups within society”.[11] Myths compete for dominance and are accepted based on the cultural codes and repertoire from which they are drawn.[12] Bathes contends that when myths become accepted, “they do not deny things… simply, it purifies them, it makes them innocent” and gives them “a clarity which is not that of explanation but that of a statement of fact”.[13] Therefore, a ‘myth-consumer’ sees an image as a naturally occurring concept, and not as part of a semiotic system made for production.[14]

Post-structuralism similarly studies the societal and cultural construction of the power structures that give meaning to our everyday lives. These structures are less evident and more fluid over time than those of semiology, thus warranting greater historical analysis.[15] Michael Foucault for example describes his work as ‘writing a history of the present’.[16] At its core, post-structuralism founded on an ethical-critical agenda seeks to problematize dominant interpretations of IR.[17] Foucault considered the work of intellectuals as not to “mould the political will of others”, but to “re-evaluate rules and institutions and participate in the formation of the political will”.[18] By examining the various forms of exclusion that constitute the world, post-structuralism aims to reveal how particular representations are materialized, falsified and are mutually dependent upon underlying power relationships. The post-structuralist research agenda involves focusing on contemporary problems and examining how a discourse has emerged historically in order to frame the understanding of that problem and its solutions.[19]

Fundamentally, a discourse can be defined as socially constructed knowledge about reality; it is the means by which social reality is conferred on events.[20] This is synonymous with Foucault’s reasoning, who argues that discourse underpins the relationship between power and knowledge, such that all identities and understanding are recognized as operations of power materialized through discourse.[21] Thus knowledge is never unconditioned and further reinforces the exercise of power underlying it. Whilst discourse may transmit, produce and reinforce existing power structures, this is what “undermines and exposes it, renders it fragile and makes it possible to thwart it”.[22] Similar to myths, discourses also compete for dominance, and become societally accepted, according to Foucault, because of their ‘regime of truth’ defined as “historically specific mechanisms that produce discourses which function as true in particular times and places”.[23] To discern if a discourse has been accepted we have to question how we have made the present seem like a normal or natural condition, and distinguish what has been forgotten in history in order to legitimize present courses of action.[24]

Myth and discourse can be considered as analogous, both articulating social representations internalized as natural and normal.[25] Similarly, on television, discourse and myths compete, informed by and representing different interest groups.[26] When applied to torture, myths and discourses serve to clarify the physical composition of the practice – what is done, who performs it and why people are subjected to it – as well providing moral justification for the actions.

The research objectives are better suited to a post-structuralist approach, as it allows for the examination of the historical, societal and political context required for understanding torture and prisoner abuse. As the nature of post-9/11 prisoner abuse remains largely classified, one could argue that this constitutes a ‘history of the present’. The openness of post-structuralism’s interpretation of international politics is also a fundamental component in research based on popular culture.

However, as the field of IR is complex and diverse, this thesis sits in the space between semiotics and post-structuralism, drawing on the influence of both, recognized by the interchangeable use of the term ‘torture myth’ and ‘torture discourse’. The influence of this myth is further explored by examining individual accounts and public opinion survey data.

Literature Review

Three diverse sources of literature are pertinent to the study of televised torture. First, empirical research from the discipline of Mass Communication was selected to provide an understanding of the impact of television on its audiences. Second, the implementation and execution of coercive interrogation methods by the US was obtained from primary and secondary sources. Finally, existing academic work that critically engages with 24 is evaluated.

Television within Mass Communication

The ‘media effects’ research tradition in Mass Communication has long considered the potential impact television has on its audiences, through the overlapping approaches of Cultivation Theory, Framing Analysis and Cognitive Priming.

Cultivation theorists study how persistent messages in television content influence an audience’s perception of reality, achieved by distinguishing light from heavy viewers and questioning their worldview.[27] On the impact of fictional television, Delli-Carpini and Williams (1996) concluded that the distinction between entertainment and public affairs content is not absolute, with strong evidence existing for “the political relevance of fictional media”.[28] This study found that participants made little distinction between fiction and non-fiction television content when discussing the environment, which reveals how audience members actively engage in the socio-political messages offered by both entertainment and factual content.

The internalization of such messages, according to Shrum, is based on a heuristic model of cognitive processing; mental shortcuts used whilst processing television messages incline heavier viewers to make such shortcuts in reality, basing judgments on the frequency, recentness and vividness of televised messages.[29] In this process, images resonate with the viewers more than text. Gibson and Zillmann (2000) identify a ‘picture superiority affect’ when the two differ in context.[30] On the other hand, Busselle, Ryabalova and Wilson (2004) argue that cognitive processing is dependent upon the programme’s ‘perceived realism’ as it is the fictional narrative which is most remembered by viewers.[31] Fear of violent crime forms the basis of Cultivation research, a consensus that ‘‘the media play(s) a substantial role in shaping beliefs and fear of crime’’, as heavy viewing of fictional crime drama predicts both a fear of crime and support for the death penalty.[32]

In the context of televised torture, these studies suggest that fictional messages are easily internalized due to their shocking visual nature and perceived realism, conditions replicated in primetime scenes of torture. As torture exists solely within fiction for the majority of Americans, one could argue these findings are more applicable to representations of torture and the ability of the practice to be unconsciously accepted despite individual political or moral beliefs.

Research into Framing and Cognitive Priming, on the other hand, is politically motivated in discerning how media messages are purposely framed by social institutions, mirroring discourses in their function and ontological worldview. Crandal, Elderman, Skitka and Morgan (2009) observed a status quo bias when torture was framed as a long-standing institutionalized practice of the US military. Presented this way, individuals both increased their support for the use of torture and endorsed attitudes that viewed it as justified and necessary.[33] Crandal et al. conclude that “a simple framing manipulation effectively increased people’s willingness to sacrifice certain cornerstones of liberal democracy”.[34]

Parallel research by Holbert, Pillon et al. (2003) investigating cognitive priming and The West Wing conclude that the fictional representation of the presidency correlated to more positive attitudes of former US presidents, both Republican and Democrat.[35] This is attributed to the ability of the show to clearly explain and articulate the president’s reasoning behind certain policy decisions, a frame distinct from that found elsewhere in the media (i.e. News).[36] These studies further indicate the political influences of fictional programs and their ability to impact public opinion.

This research suggests that the audience’s acceptance of televised messages is dependent upon how the messages are framed and internalised. As Gamson (1999) argues, fictional television is “lifeworld” content, emotionally engaging the audience and treating them as though they are physically present in the program.[37] Thus the uniqueness and proven influence of this medium warrants further investigation in its depiction of torture.

Compiling Evidence of Torture Through Contemporary Accounts of Detainee Abuse

Availability of official documents, Non Governmental Organizations (NGOs) reports and academic narrative enables a comprehensive account of the socio-political factors that contributed to American detainee abuse, and indicate conditions under which televised torture became persuasive.

Before and after the Abu Ghraib prison scandal, literature existed from journalists and NGOs outlining specific reports of detainee abuse by the American military and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) under the Bush Administration. These secondary sources are supplemented by the de-classification of primary documents relating to prisoner abuse by the Obama Administration, although much remains classified.

The most significant of the declassified documents is the August 2002 Bybee/Yoo ‘torture memo’ which formed the foundation of legal opinion upon which coercive interrogation was based.[38] Evidence that the Pentagon was aware of the abuse before Abu Ghraib is provided in the ‘Taguba Report’, although various investigations published after this point avoids discussion of command responsibility.[39] An exception is the ‘Levin Report’ which attributed the direct actions of former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld to widespread prisoner abuse through confusing mandates and insufficient interrogational supervision.[40] Nevertheless, a number of documents relating to CIA interrogation and official operating procedures in Afghanistan from 2001-4 remain classified.[41] Whilst articulating a baseline of truth, declassified documents are only significant for detainee operations in Iraq and must be read alongside NGO reports.

Unlike official sources, publications from NGOs such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch are greater in depth and scope, and published consistently from 2003. They detail further examples of Government promoted policies of prisoner abuse.[42] Reports for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) are more reliable due to greater access to detention facilities, but are not publicly available unless leaked for political reasons.[43] Despite this, the 2007 report detailing the experiences of fourteen ‘high value detainees’ at Guantanamo reveals how the culmination and differentiation of coercive methods amounted to torture.[44] The problem of using such sources is exemplified by the most recent publication of the Constitution Project, which despite investigating human rights abuses since the Clinton Administration, lacked the power of subpoena and access to classified documents, making it initially reliant on the same politically conditioned set of classified sources.[45] Although NGO reports often conduct interviews of their own, sources are concealed, which makes verification impossible. And unlike the Constitution Project, the majority of NGOs’ reports are written to elicit a political response.

Academic narratives have sought to contextualize US prisoner abuse in the War on Terror. McCoy argues that the genealogy of US sanctioned torture has not evolved since CIA research and interrogation policies of the Cold War.[46] Likewise, Michael Goodhart argues that America ‘reverted to form’ in its ‘messianic engagement’ with international human rights.[47] Michael Ignatieff and Andrew Moravcsik attribute American exceptionalism to the political structure and unique inherent belief system in American society.[48] David Forsyth has documented the precise ‘politics’ and administrational acceptance of prisoner abuse. He argues that the publicity surrounding post-9/11 detainee abuse separates it from comparable history.[49] Darius Rejali takes an alternate approach tracking the global development of coercive methods.[50]

Torture and Terrorism: A Review of the Existing Literature on 24

This section evaluates academic consideration of 24, which contends that the series has already had an impact on our reality. To date, in spite of a large resource base, 24 has received little academic attention.[51] Torture, situational morality and the state of exception have only been critically assessed in Steven Peacock’s (eds.) ‘Reading 24′. [52] In these essays, Howard reviews torture in 24’s first five series, arguing that the show influenced the real-life torture debate by placing the topic in the public’s consciousness, a position it achieves explicitly from the opening scene of Series 2.[53] However, the ticking time bomb and torture in the series have lacked systematic investigation.

Despite this, prominent journalists continue to link 24 to reality. Slavoj Zizek equates the ‘lie of 24’ to ‘Himmler’s Dilemma’ in that it is impossible for a human to retain dignity when performing acts of terror, despite Jack Bauer being considered a hero by his audiences.[54] Zizek contends that it is not the content of such scenes that are debilitating but the fact that we are being told openly about torture. Torture in popular culture “is more dangerous than an explicit endorsement of torture as it allows us to entertain the idea whilst maintaining a pure conscience”.[55] The actualization of this insight is realized in an article by Jane Mayer, as the show was undermining the core of military teaching that torture was illegal.[56] Philippe Sands’s interview with former Guantanamo lawyer Diane Beaver goes further in exploring how interrogators watched the programme on the base to give them “lots of ideas” and “go further than they otherwise might”.[57] Tony Lagouranis, an Army interrogator in Iraq, similarly states, “people watch the shows, and then walk into the interrogation booths and do the same things they’ve just seen”.[58] Like Mayer and Sands, the testimony of Lagouranis concludes that 24 had an unequivocal impact on the military doctrine of the United States.

These examples suggest that 24 impacted both military cadets and interrogators in terms of what they considered effective and morally acceptable when conducting interrogations. It further suggests that the American public and military have an inadequate understanding of, or respect for, professional non-lethal interrogational techniques, advancing the argument that torture in 24 is a legitimate field of enquiry.

Summary, Discussion and Value of Research

The review has confirmed that televised messages influence our societal-level perceptions of the world, and in the case of Crandal et al. and Holbert et al. our personal realities as well, which are subjected to a greater range of influences (i.e. personal experience). The findings of Mayer, Sands and Lagouranis further imply how 24’s representation of torture has become persuasive in military contexts where interrogations have been implemented and discussed. Contemporary accounts revealing the extent and scope of prisoner abuse provide the necessary socio-political context critical to a post- structuralist approach.

Systematic research of the structure and influence of televised torture has nevertheless been shown to be wanting. Academically, no thorough investigation of torture has been conducted on 24 despite its professed effects on interrogators. Furthermore, all prior investigations of 24 have failed to cover the eight series forming the entire canon of work. To be able to consider the impact of torture on television provides an opportunity to understand the important issue of why the practice of interrogational torture in America has gained acceptance in the post 9/11 decade. Only a few academics have sought to explicitly link popular culture on torture with military action and public opinion. Such work stands to benefit academics, fellow students and executives of ‘spytainment’ television and film.

Outline Structure

Advancing findings of the literature review and research objectives discussed, Chapter 2 contextualizes and clarifies the historical and contemporary development of the Bush Administrations’ policy of prisoner abuse. The discourse on torture in 24 is defined and critically discussed in Chapter 3; Chapters 4 and 5 evaluate the impact of this representation, societally through the analysis of American public opinion data (2001-2011) and individually through the review of relevant military autobiographies. Chapter 6 articulates the conclusions of the impact of the televised torture myth presenting recommendations for future research.

CHAPTER 2: America, Prisoner Abuse and 24

America and International Human Rights

Considered one of the greatest achievements by nation states for the benefit of individual citizens, legal norms enshrining the protection of human rights are the liberal cornerstone of modern democracy.[59] The recognition that all individuals have fundamental rights by virtue of their humanity alone, the prohibition of torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment (CID) is formally enshrined in both frameworks of international humanitarian (IHL) and international human rights law (IHRL). Governing theatres of war and peace respectively, freedom from torture and CID is considered a peremptory norm from which no derogation is permitted.[60] However, serious tensions exist around the enforceability of these measures, especially when concerning national security.

The engagement of the United States with these legal norms is described as ‘paradoxical’ by Moravcsik, who argues that America embodies “an unwillingness to apply itself to rules that the US in principle accepts as just” and which it encourages others to follow.[61] This paradox is located both structurally and historically, with the Senate either failing to ratify or placing significant procedural reservations on international treaties. This is accepted historically due to the doctrine of constitutional supremacy, permitting a crusading American exceptionalism – and exemptionalism – from the embodiment of the human rights regime.[62]

Nevertheless, the US has formally recognized a number of treaties that bind it to the humane treatment of detainees in their custody. Ratified in 1955, Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions states that “violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture” shall remain prohibited “at any time and in any place whatsoever”, a commitment codified domestically in the War Crimes Act (1996).[63] Despite playing a fundamental role in the establishment of the Declaration of Human Rights (1949), the Senate only came to ratify its supporting legislation in the aftermath of the Cold War.[64] The UN Convention Against Torture (CAT) provides an internationally recognized legal definition of the practice of torture,[65] and also bans cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment that does not amount to torture under this definition.[66] Implemented into federal law by the Torture Statute (1994), significant procedural reservations re-defined torture for Americans by moving it from an absolute to a relative crime introducing a test of specific intent.[67]

Human rights exceptionalism is located in the historical record, with CIA funded research into psychological methods of torture from 1950 to 1962, born out of the experiences of the Korean War (1950-5) and the need to master wartime advantages of their enemies.[68] In Vietnam (1955-1975) strict attention was paid to Common Article 3 in the classification of detainees and neither Prisoners Of War (POW) nor terrorists were routinely tortured.[69] In spite of this, the CIA launched its covert Phoenix Program that exercised physical methods of interrogation established by colonial France leading to widespread torture.[70] As argued by McCoy, the whole genealogy of post-9/11 American torture has not evolved since the CIA research of the 1950s, a conclusion similarly reached by an Intelligence Science Board report in 2006.[71]

Prisoner abuse and torture can also be considered as emanating from the ‘bottom up’, influenced by US military culture. Core societal values of liberty and security are downplayed in basic military training to invoke discipline, self-sacrifice and de-humanization of the enemy. Explanations of abuse span from institutionalised bullying to competitive brutality. The National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (NVVRS) concluded that military personnel who commit atrocities during war do not necessarily have abusive tendencies beforehand, substantiating research from Milgram to Zimbardo that show atrocities are committed more easily when ordinary subjects become de-sensitized in various ways.[72] Naomi Wolf further argues that longstanding episodes of prisoner abuse and rape within US military culture are comparable, as the lack of support in the chain of command creates a self-fulfilling prophecy within which impunity prevails.[73] Combined with foreign policy driven by iconography of the impenetrable ‘city on the hill’ and casualty avoidance, military action is shaped through certain channels with coercive interrogation and abuse becoming an acceptable compromise over the loss of American troops.[74]

Therefore, US military and intelligence services opened the door to generalized abuse and torture before 9/11, the history of psychological abuse or ‘torture lite’ originating in America. This created a paradox, as formal support for such legal frameworks was undermined by covert US actions, a gap widened by the public knowledge of prisoner abuse under the George W. Bush Administration.[75] This condition continues due to the enforceability of international human rights law, especially since Bush withdrew American support for the International Criminal Court in May 2002.[76]

Post 9/11: Coercive Interrogation Under the Administrations of George W. Bush

In May 2001, the United States lost its seat at the UN Human Rights Committee, a position it had held since the Committee’s inception, because of an unfavorable voting record on human rights issues.[77] The largest attack on the American homeland four months later, with the cumulative killing of 3,000 civilians in attacks on the Twin Towers and Pentagon, served to fracture American engagement with global human rights norms for the foreseeable future. How this happened is traced through legal, military and public timelines that follow.

The Legal Timeline

To work through the ‘dark side’ and counter the terrorist threat, President Bush authorised the CIA to kill, capture and detain Al-Qaeda operatives, establishing the foundation of the secret detention and coercive interrogation of ‘enemy combatants’. [78] The CIA chief legal officer John Rizzo stated that he had never seen an authorisation “as far reaching or as aggressive in scope. It was simply extraordinary”.[79]

Detainee abuse originated with policy makers and was made acceptable by the Office of Legal Council (OLC). Their successive interpretations in 2002 established that captured members of the Taliban and Al-Qaeda were not entitled to legal protection under Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions and narrowed the definition of torture to specific intent and set the physical suffering threshold to organ failure, impairment of bodily function or death.[80] This exonerated coercive interrogation if torture was a by-product of intelligence gathering. Practices amounting to the cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment of detainees were removed from US interrogations abroad, which paved the way for the opening of Guantanamo Bay and the capture and CIA waterboarding of Al-Qaeda leader Abu Zubaydah.[81]

Conceived at Guantanamo, ‘enhanced interrogation techniques’ (EITs) were authorized for military use in December 2002, following further legal interpretation that US constitutional and international law did not bind the President in times of national emergency.[82] These methods were founded on psychological techniques used historically by the CIA and diversified to exploit Arab cultural sensitivities – such as forced nakedness and the use of phobias (dogs).[83] Rescinded in June 2004, successive US Attorney Generals continued to assert the prominent interpretations of 2002.[84]

In the aftermath of the Abu Ghraib prison scandal, attempts to improve detainee treatment were made with the Detainee Treatment Act (2005), outlawing the use of CID by American forces globally.[85] President Bush undermined Congress by issuing a signed statement against the Act’s core provisions, continuing to authorize enhanced interrogations, and introducing the Military Commissions Act (2006). This stripped detainees of their right to habeas corpus, granted retroactive immunity to soldier’s accused of war crimes and made testimony under torture permissible in the Guantanamo commissions.[86] Bush continued to thwart Congressional efforts to regulate CIA interrogation right to the end of his second presidency.[87]

The legacy of the Bush Administration is the predominant concern to prevent subsequent attacks on the homeland that overwhelmed all other considerations: “Customary international law did not even come into it”.[88] There was no balance between a tough response to 9/11 and respect for the rule of law and presumed American values.[89] Upon his inauguration, President Obama rejected Bush-era terminology of ‘enemy combatants’ and ordered compliance with domestic and international law in detainee treatment.[90] Yet he has continued to support military commissions over federal courts in the trial of suspected terrorists and has not fulfilled his first election promise to close Guantanamo.[91]

The Military Timeline

Justified as containing the ‘worst of the worst’ and inmates of high intelligence value, Guantanamo was the testing ground for coercive interrogation techniques authorized for the Military and inspired by the SERE program. Applied to ‘break’ prisoners, these were considered acceptable as they had been similarly used on US soldiers.[92] Detainee abuse at Guantanamo (2002-5) was entirely the result of policy design, a conclusion supported by the involvement of Behavioral Science Consultation Teams of psychologists and medical staff to facilitate interrogations.[93]

The origin of prisoner abuse in Afghanistan is less straightforward. Operations from October 2001 started humanely but overwhelming numbers of detainees, their shifting legal status, a prevailing risk averse military culture and inexperienced interrogators led to rampant CID.[94] This was exacerbated by the manipulation of ICRC visits and the cover-up of detainee deaths in US custody.[95] With the transfer of attention and resources to the invasion of Iraq, detainee treatment only improved with the introduction of NATO forces into the country (2003).[96]

The war in Iraq should have been different with President Bush formally stating that the Geneva Conventions fully applied to combatants and civilians. As the Schlesinger Report concluded though, coercive interrogation techniques ‘migrated’ to Iraq, exacerbated by the authorization of similar techniques in Afghanistan and the “GTMO-ising” of detainee treatment with the transfer of Guantanamo Commander General Geoffrey Miller to Head of Detainee Operations in Iraq.[97] Abuse was also influenced by the presence of the CIA and private military and security contractors in interrogations, the former having authorization to use harsher techniques whilst the latter formally stood outside the chain of command.[98] The Pentagon was aware of such abuse before the Abu Ghraib pictures, with the publication of the Taguba Report detailing “sadistic, blatant, and wanton criminal abuses” there.[99]

Gains in strategic intelligence were minimal despite the abuse but cost the US much in political and security terms. Abuse in Afghanistan did not prevent the situation in the country from deteriorating and the increased stability in Iraq from 2007 is more attributed to the cessation of coercive interrogation.

The Public Timeline

The public torture debate in America started immediately after 9/11, with Harvard Law School Professor Alan Dershowitz advocating the introduction of judicially administered ‘torture warrants’ as a condition to best regulate interrogational torture.[100] Despite an open media debate on the efficiency of interrogational torture, prisoner abuse did not fully enter public consciousness until the release of the Abu Ghraib photos in April 2004. The Administration response was to blame a few ‘bad apples’ confirmed by the trial of eleven lower-enlisted personnel rather than systemic military practice.[101]

The ‘myth’ that the Administration was unaware of these actions was dispelled when details of CIA ‘black sites’ and a global program of rendition were reported in the media, and the Bush Administration formally admitted the program’s existence in September 2006.[102] In February 2008, former-CIA Director Michael Hayden testified that three Al-Qaeda suspects were water boarded under interrogation by the CIA, and the Pentagon dropped charges, without explanation, against 20th hijacker Mohammed al Qahtani, confirming that admissions made under torture are not admissible in court.[103]

The torture debate was reignited with the December 2012 (US) release of Kathryn Bigelow’s film Zero Dark Thirty, recounting a fictional depiction of interrogational waterboarding leading to the capture of Osama bin Laden. This was subsequently attacked in an open letter by Senators McCain, Feinstein and Levin for its ‘grossly inaccurate’ and ‘misleading’ representation.[104]. As Glenn Greenwald at the Guardian stated, “Nobody complained that the film depicted torture. The complaint was that it falsely depicted it as vital in finding bin Laden and thus portrayed it in a falsely positive light.”[105]

In conclusion, US torture policy reflects America’s paradoxical relationship with international human rights law and a permissive military culture of abuse that stretches back to Vietnam. More recently, lawyers and academics have deemed coercive interrogational techniques as permissible, effective and acceptable. Clarification of the origins and reported extent of detainee abuse under the Bush Administration facilitates critical evaluation of torture discourse in 24 and establishes the necessary contextual foundations upon which the analysis of American public opinion and military autobiographies is based.

CHAPTER 3: Establishing the Myth – a Discourse Analysis of Torture in 24

Introduction to 24

Jack Bauer has 24 hours to find and disarm a nuclear bomb planted in Los Angeles by ‘Second Wave’, a terrorist group supported by Middle Eastern States, and to defuse a political conspiracy for retaliatory strikes by exposing false evidence. This is the story line for season 2 of 24, the first series written, produced and broadcast after 9/11 and the starting point for this discourse analysis. In brief, it is a counterpoint to 9/11, an effective homeland security, foreign strikes avoided and dodgy intelligence exposed. History has been reworked and played back to the American public.

Debuting two months after 9/11 and based on the work of the fictional Counter Terrorism Unit (CTU) to prevent attacks against the American homeland, 24 quickly became the television program of its ‘global war on terror’.[106] Contextually unique, 24 spans both Bush Administrations with seasons two to eight (2002-2010) a product and zeitgeist of the intense post-9/11 American fear of terrorism. 24 provides an invaluable popular culture resource as a window into domestic American thinking in the post-9/11 era.

The Structure of 24

Organized around a day in the life of CTU protagonist Jack Bauer, each 24 series is shown in real time and encapsulates various ticking bomb scenarios where characters must thwart impending terrorist attacks before the day is out. The impact of passing time is stylistically portrayed through the use of a ticking clock and split screen showing the actions of multiple characters in ‘real time’. Similar in structure to news or live sports events, 24 places greater importance on this core narrative structure than complexity of the characters or plot.[107] Adding to dramatic suspense, this puts large demands on the audience to watch every episode, a key factor in its critical and commercial success.[108]

24 plays on collective fears that America will be targeted and attacked again, “tapping into the public’s ‘fear-based wish fulfillment” to have people like Bauer who will “do whatever it takes” to save society from harm[109]. Fiction therefore becomes very personal as it directly refers to tangible and immediate fears that parallel the real, bringing the necessity of interrogational torture into public view and debate.[110]

Discourse Analysis Method

The aim of this analysis is to reveal the specific discourse about the use and effectiveness of torture in 24 when used as a tool of counterterrorism. This discourse analysis spans 170 episodes of 24 programming from seasons two to eight and broadcast between 2002 and 2010.[111] To conduct the analysis it was necessary to identify ‘torture narratives’, the interrogational torture of an individual that could span many scenes or episodes, and could be orchestrated by individual or multiple interrogators. To do this it was necessary to include all forms of torture, whether conducted by ‘government officials’ working directly for or in the interest of the US government, ‘terrorists’ ideologically working against US interests or ‘criminals’ seeking financial gain. [112] A torture narrative tells the story of victims of torture and their orchestrators in the series.

To locate torture narratives, the content of each series was analysed using documentary sources and episode synopses from 24’s most comprehensive fan page even though this may not be an entirely reliable academic source.[113] From this review, 43 torture narratives were identified and viewed on DVDs and the visual data coded using an analysis frame for every narrative. [114] The analysis frame was generic in focusing on how torture was portrayed, the analysis separated into five component parts: 1) demographic information of the victim, 2) demographic information of the orchestrator(s), 3) justification for torture, 4) the methods used and 5) the outcome. During transcription, this was further expanded to include information on the specific justification for torture and its duration, both seen and implied through the real-time structure of the programmes.

The discourse analysis was conducted on 38 of these narratives, focused exclusively on State or terrorist orchestrators and 5 narratives involving torture by criminals were excluded for lack of relevance. Two sub sets of data are contained within the 38 narratives, one comprising 26 narratives conducted by Government officials of which 19 exclusively deal with terrorist suspects and the other comprise 12 narratives conducted by terrorists. The full results of the discourse analysis and sample frame used form Appendices 1 and 2.

Findings: Constructing 24’s Discourse on Torture

This discourse analysis reveals that a ‘myth’ of the effectiveness of torture and counterterrorism has been presented to the American public as a natural and normal condition. Taking a post-structuralist approach of ‘writing a history of today’, core components included and omitted from 24’s torture discourse will be reviewed before considering who the beneficiaries of such a myth presentation are.

The discourse analysis builds mainly on the portrayal of the 26 US orchestrated torture narratives on 24, shown in Table 1, because they comprise two thirds of torture narratives with which the American public are more likely to self-identify.

Table 1: Main Findings of the Discourse Analysis of Torture in 24 – US Government Orchestrated Torture

Torture in 24 is exclusively used to gain information in the context of counterterrorism. US officials (especially Jack Bauer) on eight occasions ‘go rogue’ and perform unsanctioned interrogational abuse and are more likely to act alone in a ratio of six to four. [115] The victim profile of US orchestrators is predominantly constructed of domestic terrorists, American in nationality, whilst those with Middle Eastern descent are surprisingly under-represented. The success rate of securing information within the time available is 46% rising to 53% of the terrorist only victims. Reasons for non-success being escape innocence (no information to yield) and failure to break the terrorist being interrogated in the time allotted.

When compared with the terrorist orchestrated torture subset (Table 2), the striking difference is the lower success rate, in part due to Jack Bauer’s resistance to ‘breaking’ and the higher identity of orchestrators of Middle Eastern origin.

Table 2: Main Findings of the Discourse Analysis of Torture in 24 – Terrorist Orchestrated Torture

A torture narrative in 24 may include several different types of interrogational torture. Ten common methods of torture are represented across both cohorts of US and terrorist orchestrators (See Chart 1). Predominantly physical methods of torture are used, beatings and mutilation being the most common. Only US officials use psychological methods in a limited number of cases, indicating access to a wider repertoire of coercive interrogational methods.[116]

Chart 1: Methods of Torture on 24[117]

What is Remembered?

Three core components of the myth can be drawn out of the discourse analysis of torture on 24: that interrogational torture is successful in limited time with unsanctioned torture being the most effective, that torture is conducted through physical methods, and that those interrogated will break eventually.

In the 24 hour time period covered by a series, about a half of those interrogated abusively will yield information. In terms of intelligence outcomes, extrajudicial and non-sanctioned abusive interrogation (75%) by US officials is more than twice as successful as sanctioned counterparts (33%). The significant rise in success is attributed to the actions of Bauer and US interrogators operating alone, without supervision or accountability.[118] Although Bauer’s fictional superiors oppose this, the audience accepts such coercive actions because the results are justified to save lives.[119] Within this a ‘torturous double standard’ is evident, other characters employing unsanctioned coercive techniques being formally punished whilst Bauer is not.[120] The discourse shows that US officials have to ‘cross the line’ legally and physically to elicit information to counter the terrorist threat.

Table 3: Success Rates of US Orchestrated Torture on 24

This representation of ‘rogue’ torture coincides with the overwhelming use of physical methods of torture on 24. The constant use of mutilation, beatings and electric shocks by both American and terrorist orchestrators presents torture as a constant condition across the ideological spectrum.[122] Positively correlated with unsanctioned interrogations is the brutality of the method used, greater brutality resulting in greater intelligence success.[123] The articulation of this is most poignantly signified in the unauthorized interrogation of Ryan Burnet, whose electro shock torture by Bauer was cut short by the President. After the failure to get Burnet to talk using humane methods, the White House is identified as the next terrorist target and attacked; leaving the audience in no doubt that coercive interrogation should have been continued.[124]

Most critically, however, is the presumed guilt of all victims and the inference drawn that they deserve such treatment; the question is not if they have the answer required, but how long they can hold on to it without breaking[125]. As ‘everyone breaks eventually’, guilty victims are only prevented from this fate by escape, an option not open to real detainees. [126]

What is Forgotten?

In establishing the myth of successful interrogational torture as a counterterrorism ‘regime of truth’, 24’s torture discourse omits a number of real concerns about the efficacy of physical torture and existence of the ticking bomb scenario.

In order to elicit as much information in the shortest timeframe possible, 24’s protagonists induce maximal physical pain in the shortest amount of time. It ignores that pain is considered a poor technique that generates false confessions and what the interrogators want to hear.[127] It is also falsely premised on the medical assumption that more pain is felt the longer it is endured, when the opposite is true.[128] This view is corroborated by scientific research on retrospective amnesia; Ribot’s gradient states that the higher amount of trauma sustained on the brain the greater risk of short-term memory loss or the expression of higher confidence in the wrong information.[129] Interrogators too become more susceptible to misinformation under severe time constraints.[130] Highly physical methods of interrogation are less effective under a ticking bomb scenario, although the problem of yielding inaccurate intelligence is never confronted on 24.[131] It can be argued that the over-reliance on physical techniques actually undermines the aim of state-sponsored torture: for the results to be undetectable.

Interrogations are more successful when they employ non-coercive techniques, such as attempts to build rapport. This is based upon keeping a prisoner comfortable and gaining their trust, whilst also requiring a substantial amount of evidence to corroborate detainee testimony.[132] 24’s discourse on torture sacrifices these traditional law enforcement and military interrogation techniques with a proven rate of success to ‘fit’ the shows ticking bomb and limited time narrative.[133]

It is 24’s core ticking bomb narrative that makes interrogational torture justifiable to its audiences, taking a hypothetical thought experiment and applying it to US counterterrorism as if real. Such a scenario is premised on three core conditions that 24’s discourse on torture promotes: that there is sufficient urgency to torture, that accurate information is given, and that the suspect has the information required.[134] However, in real-life these conditions serve to work against each other; limited time equals limited effectiveness, and the more violent methods used the more likely they are to yield inaccurate information, odds dropping further when the victim actually does know something, as do 75% of the victims on 24.[135] Here detainees have a psychological advantage over their interrogators in knowing how long they have to withstand the pain; they may intentionally lie, misinform, or be trained in the resistance of such techniques.[136] Critically, the necessity any ‘ticking bomb’ places on government authorities can only ever be discerned in retrospect, whilst 24 is based upon knowing beforehand the precise nature of the threat.[137]

The ticking bomb scenario is a hypothetical construct, influential because it requires the viewer not to imagine what they would do in that situation, but what they would be willing to allow others to do on their behalf.[138] Even the staunchest defenders of enhanced interrogation, historically and contemporarily, have failed to provide a specific ‘time bomb’ case under the guise of national security. Darius Rejali provides reasoning for this as he traced the existence of the ticking bomb scenario back to 1960’s French war fiction: the ticking bomb scenario created and existing exclusively in fiction, based on a situation of necessity invariably absent in real life.[139] This is arguably more dangerous, as it “allows a plot to be dreamed up in Hollywood to determine the limits of moral authority”, and the durability of the ticking bomb is not about understanding the current torture debate but shutting it down; indeed the ticking bomb scenario is constructed to be un-debatable.[140]

In prioritizing the illusory ticking bomb scenario, and the physically coercive forms of un-sanctioned torture it justifies, the larger impact of American state-sponsored torture is never alluded to in 24, most pertinently that coercive interrogation actively undermined foreign policy initiatives in Afghanistan and Iraq.[141] International and domestic human rights law is furthermore never referenced and disregarding the moral dilemma of breaking the law advances the myth that the torture of terrorist suspects can be justified.

How Does This Rewrite the History of Abuse?

The discourse of torture on 24 gains its ‘truth effects’ because it takes place in the context of real-life societal debates and events in the War on Terror presenting a fictional alternative to Abu Ghraib and establishing interrogational torture as an effective and necessary counterterrorism tool. Moreover, the legacy of US prisoner abuse is justified and accepted when understood through the actions of Jack Bauer in a hypothetical ticking bomb situation. 24’s torture discourse rather serves to fuse interrogation with torture in the minds of its audiences, the 33 hours of implied interrogation on the show in which detainees are held between the 5 hours of on screen torture, making the two synonymous.[142]

To become persuasive, significant history is omitted through this discourse. Putting aside the ineffectiveness of physical torture and the fictional existence of the ticking bomb scenario, 24’s torture discourse omits that the majority of those geo-politically arrested in real life were innocent, as high as 70-90% estimated in Iraq.[143] More fundamentally, 24’s torture discourse or its myth in popular culture does not consider what the nature of torture actually is and the impact it has on the lives of its victims and orchestrators. Tortured under the Gestapo, such reality is best exemplified in the writings of Jean Amey when he states that “Only in torture does the transformation of the person into flesh become complete…the tortured person is only a body, and nothing else besides that”, for what we do not comprehend is that breaking a person’s body is breaking a person’s mind, and when the body will heal the mind does not.[144] In this way, the discourse of torture on 24 has served to de-sensitize the American public in its representation of the effects of torture.

In Whose Benefit?

Who benefits from the torture myth presented in 24? The fight against terrorism is portrayed as the Bush Administration defined it: “an all-consuming struggle for America’s survival that demands the toughest of tactics”.[145] The presentation of torture in this way favors the security and foreign policies of the George Bush White House in two ways; distinguishing ‘us’ from ‘them’ and identifying the ‘enemy within’ through the torture of largely domestic terrorists. US torture is accepted by audiences as contextually justified. Both sides use brutal methods, but Americans have more torture tools at their side and are more successful at it, because they are portrayed as using it for positive ends – the saving of innocent lives — whilst torture orchestrated by Middle Eastern perpetrators is represented as shockingly brutal and derived from sadistic pleasure.[146] This also serves as a justification for American torture as Middle Eastern, and by inference, Islamic terrorists are portrayed as only understanding and responding to these methods and if coercive methods are not used by American forces on the ground, they themselves might become the subject to such brutality.

24 serves to further raise the show’s ‘fear factor’ by presenting the ‘enemy within’ over the ‘exotic other’, reminding viewers that those who claim to love America are often as dangerous as those who claim to hate it.[147] Critically this allows the myth to extend interrogation torture to anyone on US soil, which is strictly illegal in domestic US law.[148] By initially focusing on international terrorist groups, this promoted the Bush Administrations’ interests by creating a climate of fear (and necessity) that justified its interpretation of the law and the enforcement of strict homeland security initiatives such as visa restrictions, warrantless wiretapping and more recently the data-mining of internet communications through Prism. [149]

More than this, however, Jack Bauer became a symbol of American patriotism and icon in American politics with key political figures endorsing him and his actions.[150] Former-Secretary of Homeland Security Michael Chertoff spoke publically of his admiration for 24 and how it reflected the reality of American counterterrorism operations: “[They are] always trying to make the best choice with a series of bad options…to weigh the costs and benefits of a series of unpalatable alternatives…That is what we do every day”.[151] Using 24 and Jack Bauer as a frame of reference for real events perpetuates the misperception that 24 represents the reality of counterterrorism.

On an individual level the torture discourse also advances the right-wing politics of the series creators. Joel Surnow, 24’s co-creator and executive producer, espouses 24’s pro-torture stance admitting: “I think torture does work. It would work on me! I believe torture has been around since the beginning of time because it works”, adding that he would “Hope to do it” if he ever found himself in a comparable situation to Bauer.[152] Rober Cochran, 24’s other creator and a member of the Liberty Film Festival dedicated to promoting conservatism through entertainment, agrees that “Joel’s politics suffuse the whole show”.[153]

Whilst it may spread the message of conservatism, the producers of 24 publicly denounced any benefit from the show’s discourse on torture, pleading distance from it instead. Surnow argues that “Young interrogators don’t need our show…what the human mind can imagine is so much greater than what we show on TV”.[154] Referred to as his “improvisations in Sadism”, Howard Gordon insists scenes of torture in 24 are constructed in the imagination of the show’s writing team and a similar argument is advanced by Kiefer Sutherland (who plays Jack).[155] In this respect the individual politics of Surnow and those represented on 24 can be argued to indirectly impact its audiences; did Surnow’s worldview on torture have a greater impact than the official protocol for inexperienced soldiers on the ground?

The US soldiers themselves are considered another beneficiary of the torture discourse, as under situational pressure they turn to the torture myth for information. Here the myth clarifies torture in the minds of servicemen, and although they may not go out and replicate the precise method, they consume the myths about the effectiveness of physical methods and the immediacy that ticking bombs generate for result. As former Army interrogator Tony Lagouranis states, “In Iraq I came to believe, as did many others that the ticking bomb was not hypothetical… When the infantry brought us a prisoner and said that he was an insurgent, oftentimes all we could hear was the ticking of a bomb”.[156]

Finally, the American public itself as the primary myth consumer can be understood to benefit from the torture myth. Eric Greene argues, “These myths, stereotypes and misconceptions survive not to the extent that they are true but to the extent that they are useful”, the myth accepted by American society because of the common wish fulfillment that “year after year, threat after threat, Jack Bauer fulfills our frustrated desire for a Government equal to the challenges of the day”.[157] The American public feels secure in knowing that there are people like Bauer out there who can “deal with this world”, his methods justified in protecting the nation.[158] “It is not whether torture works, but why so many people in our society want to believe that it works” comments Ann Applebaum.[159] To this extent, 24 fuels the public debate by placing torture as a viable topic within the public consciousness: “we have incorporated these images into out psyches, and in doing so, could unknowingly be legitimizing their use in the post 9/11 political landscape”.[160]

Conclusion

Part of a post-9/11 paradigm shift in television content, 24 embodies a new form of ‘spytainment’ where both the amount and type of torture scenes depicted has grown exponentially.[161]The Parents Television Council concluded that 24 is the “worst offender on television”, leading the trend with the most frequent and graphic representations of protagonists using torture.[162]

The discourse analysis of torture promoted in 24 confirms trends in post-9/11 American prime-time television that torture is carried out by the ‘good guys’ as a patriotic act in a situation of necessity. As Sutherland and Swan conclude, “Bauer does not confine himself to the rules of Government; instead he adopts the warfare tactics of terrorists…There are no questions that these tactics are effective, but could we view them as morally justified if Bauer was not protected by the identity of a hero? Certainly the law does not recognize this defense”.[163]

In conclusion this Chapter represents the first systematic attempt to discern the specific nature of torture on 24. The discourse analysis of 24 promotes the myth that:

- Interrogational torture produces intelligence, and yields the best results when not authorized. The more brutal the torture the more successful the results.

- Torture is necessary and justified for the protection of American lives in the fight against domestic and international terrorism. No other approach is considered.

- The presentation of the necessity of interrogational torture as a counterterrorism tool is advanced in terms that mirrored the Bush Administrations’ arguments to visit the ‘dark side’.

- No one is immune; anybody considered to be withholding information can be tortured during an interrogation, including American citizens and known innocents.

How this myth has been consumed is considered next in a review of US public opinion on the acceptability and justification of torture, and its impact on US military practitioner action.

CHAPTER 4: Analysis of United States Public Opinion Data on Torture

Introduction

American public opinion shifted significantly and favourably in support of interrogational torture as a tool of counterterrorism in the decade after 9/11. This chapter reviews the findings of American public opinion data to identify the influence of the myth and to suggest how televised messages influence beliefs and values. The data analysis, findings and reliability of results are considered. The full data sets are in Appendix 3 and 4.

Framework of Data Analysis

The survey framework is modeled upon a previous study by Gronke and Rejali (2010) that charted US public opinion on torture from 2001 to 2009.[164] This survey expands this original dataset, including polls conducted up to 2012 and extending the scope of the study by including polls that indirectly refer to torture.[165] A total of 62 polls are analyzed and split into two datasets on general attitudes (56 polls) and the acceptance of certain torture methods (9 polls). Specific details of this enlargement are shown in Table 4. New public opinion polls were located reputably through the Roper Center of Public Opinion Research and represent the opinions of more than 100,000 Americans over the 11 years surveyed. [166]

Table 4: Comparison of Datasets

[167]In the larger general attitudes dataset, question type has been further categorized between ticking bomb or justifiability questions.[168] Although both are set in the context of counterterrorism, supporting the use of torture as morally justified, they are not mutually exclusive. Stating that torture could be justified in one situation does not mean that it should be used. Therefore respondents are not asked their views on the effectiveness of torture; rather this is presumed in their answering of the question. American public opinion on torture is being gauged through the questions asked.

The polls analyzed are reliable to the extent that they draw on representative samples of US registered voters and are conducted by reputable polling organisations.[169] The average poll sample size is 1,607 respondents with the majority of polls conducted by telephone interview (51 polls) or internet surveys (11 polls).[170] Overall, a range of twenty-seven questions are asked; for uniformity answers are presented as either an overall justified (often/sometimes) or unjustified (rarely/never) response.[171] Questions are omitted relating to legal frameworks surrounding torture, or which define the question in partisan terms.

One outlier result (Time / SRIB, August 2006) was excluded from data analysis as it fell outside 3 standard deviations of the mean of the dataset, indicating a statistical anomaly beyond 99.5% of the expected results by normal distribution.

Findings of the American Public Opinion Survey into Attitudes on Torture and its Methods

Prior to 9/11 it is difficult to assess the attitudes of the American public towards torture; questions on torture were not routinely asked in surveys and ‘torture’ itself was not in the public’s consciousness.[172] Limited poll data suggests a high American public threshold opposed to torture, a poll conducted by the International Red Cross (1999) indicating that 65% of Americans opposed torture to gain military information.[173]

Gronke and Rejali (2009) concluded that the American public opposed torture throughout both Bush Administrations, noting paradoxically that this switched in the first year of the Obama Administration as a small majority came to favor the use of torture to fight terrorism.[174] The extension of the range and scope of this research has not changed this conclusion; the long-term average in support for torture stands at 43.5% compared to a 51.2% opposition to the practice.

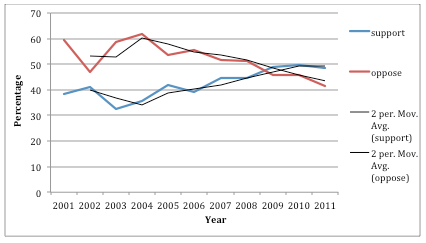

However, this masks the trends in the data that the wider analysis of US public opinion reveals. A rising long-term trend in support for torture can be seen when used to counter terrorism, evidencing a 10 percentage-point increase in support for the practice throughout the survey period. Every polling organization surveyed substantiated this general trend with the overall results of the extended survey displayed in Chart 2. Thus one can infer that over time a higher percentage of the American public came to view interrogational torture as an effective method of counterterrorism.

Chart 2: Overall Results of American Public Opinion Survey

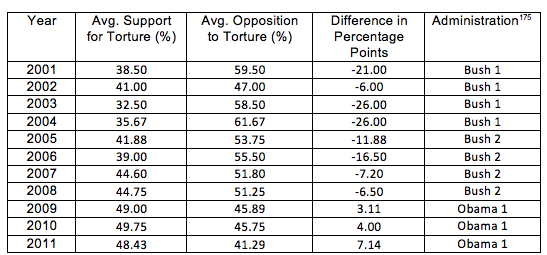

In the 20 polls (36% of the sample) commencing from the end of 2008, average support for torture alone rose by 5%. Identified as confusing and insignificant by Gronke and Rejali in the final year of their study, this has continued and widened since. In comparison with their 2001-2009 findings, this survey reveals that in the subsequent three years support for torture has risen on average by 2.7%, whilst opposition to the practice has dropped by 3.8%. Yearly averages in the support and opposition of torture and difference in percentage points is presented in Table 5.

Table 5: Average Support and Opposition to Torture (2001-2011)

[175]Clearly depicting three phases of development across presidential administrations, the 20+% disparity between support and opposition to torture under the first Bush Administration (2001-5) gradually narrows through the teens then to under 10% in the final two years of Bush’s second administration (2005-9). [176] The balance of public opinion then changes in the first Obama Administration (2009-12) where public support for torture overtakes that of opposition with the difference widening to the end of the study period.

Regarding the method dataset, polls present American public opinion on the applicability of seventeen coercive interrogation techniques, thirteen of which were officially approved for military use.[177] Results indicate the majority of the US public consistently opposed the most excessive techniques, namely sexual humiliation (85%) and electric shocks (80%).[178] Although insufficient information exists to draw statistical trend conclusions, the technique most questioned – waterboarding – sees a substantial rise in support of over 34 percentage points from 2004-2011. Further, equally coercive psychological techniques such as forced nakedness and sleep deprivation retain majority support throughout the survey period. As the public was questioned on some techniques that only exist in fiction (electric shocks) this indicates a societal misunderstanding of the types of interrogational techniques used on detainees and their potential impact.

Analysis of Results

Support for torture is dependent upon the type of questions asked, specific wording and methodological differences between polling organizations. Questions presented in a ticking bomb format elicited lower average support for torture (40%) than questions that asked if the practice was justified (47%). Such rise in support attributed to the elimination of moral considerations through justifiability questions. In asking whether torture ‘can be’ justified in the fight against terrorism, questions imply a future state of necessity that inclines a greater number to conclude torture can be sometimes justified.[179] Interrogational torture on 24 is presented similarly; the morality of the argument (‘should we torture’) is never considered, replaced by a utilitarian reasoning that actions are justified in the circumstances.

Wording also impacts on poll results; the four polls in this survey indirectly referencing torture revealing 52% public support for the practice. An Angus Reid poll (2011) found support for ‘enhanced interrogation’ increased to 57%.[180] When questions on torture and interrogation are more ambiguous than explicit, similar to the torture myth, torture is only referenced directly when committed by villains and terrorists, serving to distinguish ‘us’ from ‘them’. There is therefore a misperception within the American public about exactly what constitutes torture and specifically who carries it out.

The polls themselves are indicative of the changing debate on torture in American society. Polls are unevenly distributed across the survey’s timeframe as questions on torture were not repeatedly commissioned until 2005 through to 2009, with interest spiking again in 2011. Interest is therefore shaped by reality, initial curiosity consistent with the re-election campaign and second term in office of President Bush (2005) and tailing off after Obama declined to conduct a public inquiry into his predecessor’s actions.[181] In May 2011 Osama bin Laden was captured and killed, re-igniting the debate over the effectiveness of coercive interrogation in his detection.[182]

Contemporary events similarly impact the writers and producers of 24; torture in the season released directly after Abu Ghraib changing from “an infrequent shock to the main thread of the plot”.[183] Nacos concluded that 24’s producers used the scandal “to incorporate more torture scenes and justify this interrogation method as an effective weapon in the war on terror”.[184] This reveals how the news and entertainment feed off each other in their effort to reinterpret past events more favorably.

Discussion of Results

Overall this rise in US public support for torture can be attributed to many factors. Gronke and Rejali argue that it has become a bi-partisan symbol representing hawkishness on national security issues.[185] A cross-sectional study by Miller (2010) found a positive correlation between per-capita income and opposition to torture, suggesting deteriorating economic conditions can impact public attitudes towards torture.[186] Nevertheless, the distinct paradigmatic shift in post-9/11 television, ‘spytainment’, can also be considered a viable option in explaining this change.

In an exclusive YouGov poll (2012) commissioned by Amy Zegart, attitudes towards torture and terrorism were for the first time measured against frequent and infrequent viewers of intelligence-themed film and television, finding that frequent watchers of this genre were significantly more likely to approve the torture of terrorists.[187] When questioned on individual methods, a higher proportion of frequent watchers agreed to every technique bar one, as means to elicit information about possible terrorist attacks in the United States.[188] Critically, the poll further reveals that frequent television watchers of this genre are more radical in their views than movie watchers.[189]

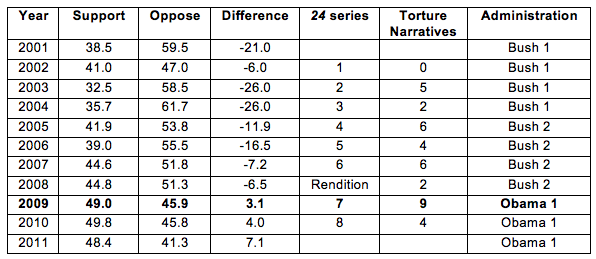

Although a one-off poll, these findings statistically correlate frequent intelligence-themed television watchers with support for torture. However, the precise causation of this link will never be ascertained; regular fans of spy genres could naturally be more radical in their beliefs, and therefore predisposed to this genre because of views they already have.[190] Despite this, there is a degree of overlap between the discourse of torture on 24 and findings of the US public opinion survey, represented visually in Table 6 and Chart 3. Season 7 contains the highest frequency of torture on 24 – 33% more than the next closest series. Shown from January 2009, this coincides with the first time average US public support for torture surpasses that of its opposition (see highlighted row Table 6). During this season 24 received its highest Neilson ratings with the show averaging 12.62 million viewers per episode.[191]

Table 6: 24 and American Public Opinion[192]

Chart 3 presents the intersection between US public opinion on torture and the popularity, viewing figures and the frequency of torture narratives within each series of 24. [193] As previously concluded, US public support for torture follows a long-term upwards trend; once the majority support of torture is ascertained in 2009 the gap between torture and its opposition only widens. This indicates that public support for torture increases at the expense of opposition to it; more respondents directly switch from opposing to supporting torture. This long-term shift in public attitudes could be due to the persistence of fictional torture myths in society becoming accepted and internalized by proportions of the public over time; they have become ‘regimes of truth’, snippets of reality that outline America’s counterterrorism policy and it is hard to identify other long-term factors that would bring about such a substantial change in the way the American public views torture.

Chart 3: Public Opinion, Torture Narratives and Viewing Popularity of 24

Reliability of Results and Conclusion

This chapter demonstrates areas of convergence between 24 and US public opinion, results showing a significant upward trend in majority support for torture since 2009; whether or not 24 played a specific role in this cultural shift, this trend cannot be overlooked.

A complex and contradictory phenomena, error is inevitable in all public opinion polls, as the perfect sample and worded question is non-existent. Although tracking change in attitudes over time, public opinion cannot assess causation; it is impossible to determine if popular culture is the real cause of difference.[194] Furthermore, the survey administration processes can impact the reliability of findings; respondents answering telephone interviews are prone to interviewer bias whilst Internet surveys are undermined by coverage error.[195]

Polls in this review are also affected by participants’ response accuracy when they refuse or do not know an answer, with large numbers of don’t know / no opinion responses tending to skew the results in favor of torture, although there are relatively few of these. [196] The reliability of this research is most affected by measurement error that comes from comparing data across different questions and polling organization.[197] Data available on US opinion on torture is too small to comprehensively compare ‘apples with apples’; attempts to overcome this are made by categorizing the questions into question type which allowed for some statistical reliability on specific issues such as ticking bomb, justifiability and methods. Further reliability problems arise from conducting polls over time through longitudinal surveys during which meanings and methodologies change.[198]

Cross-sectional opinion of 18-24 years olds – the most popular demographic of 24 audiences – might have enabled a correlation between viewing and opinion but data was not uniformly available to be of statistical significance. Furthermore, due to the lack of public opinion data on American attitudes to torture before 9/11, longstanding opinion cannot be discerned and change in attitudes not fully contextualized.[199]

Despite this, results from public opinion polls have high external validity and their results can be generalised across the population under real world conditions.[200] Furthermore, internet and telephone surveys are effective with the survey dates closely corresponding to periods when 24 was televised. This represents an accurate result of the post 9/11 period under study. The impact of this long-term shift in American opinion, and the televised torture myths underlying it, will now be examined in an individual context in relation to interrogators’ experiences in Afghanistan and Iraq.

CHAPTER 5: Televised Torture and the United States Military

Introduction

“It was like having the opportunity to be there watching myself do it,” said Keller, “and that is pretty God-awful, to actually have to come to terms visually with what you are doing. It’s no longer just watching somebody in a movie do it… No, you’re watching somebody really doing it in real life – and this time… they’re wearing the same uniform as you”. [201]

This chapter looks at how popular culture affected the behavior of military interrogators in the theatre of the ‘war on terror.’ It does this by reviewing military autobiographies describing the interrogation of Iraqi and Afghani detainees set against the situational factors the military faced.

Evaluation of Sources Used