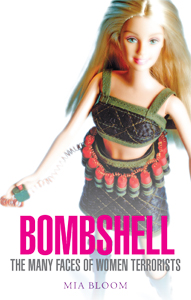

Bombshell: The Many Faces of Women Terrorists

By: Mia Bloom

London: Hurst, 2011

Mia Bloom’s Bombshell: The Many Faces of Women Terrorists is an important contribution to the literature on the varied roles women perform in organized violence networks outside the formal structure of the state. As Bloom notes, it is crucial to understand better what the roles of women have been and are changing into, not merely for academic reasons but for policy, strategy, and moving forward in an increasingly complex and violent world. In the U.S., political and military leaders have mostly been unprepared for the growing and morphing roles of women as suicide bombers and more generally in “terrorist” organizations. Their own patriarchal ideologies and expectations have made them not see developments, putting us all at a disadvantage and at further risk.

Mia Bloom’s Bombshell: The Many Faces of Women Terrorists is an important contribution to the literature on the varied roles women perform in organized violence networks outside the formal structure of the state. As Bloom notes, it is crucial to understand better what the roles of women have been and are changing into, not merely for academic reasons but for policy, strategy, and moving forward in an increasingly complex and violent world. In the U.S., political and military leaders have mostly been unprepared for the growing and morphing roles of women as suicide bombers and more generally in “terrorist” organizations. Their own patriarchal ideologies and expectations have made them not see developments, putting us all at a disadvantage and at further risk.

Bombshell is written intentionally to be accessible to non-specialists as well as to make a contribution to the expert material in the field. Bloom writes without jargon, provides a good deal of context and background, and clarifies when her research yields results that are different from other studies. Mainly, Bloom points out that media and previous research portray women as background to the real centers of terrorist campaigns: as dupes of men, male leaders and male opinion makers. Her analysis is far more nuanced and layered, showing numerous motivations and the many significant parts women play in different conflicts around the globe.

Ultimately, Bloom gives us a clear, though textured, analysis of the webs in the circumstances and women’s changing roles so that we should no longer ask such simplistic questions of women’s roles in religio-political struggles as: are women there by coercion or choice? Bloom’s work offers us the overlapping frameworks of what she calls “The Four Rs Plus One” (234). When looking at different conflicts and groups across regions, Bloom demonstrates that women become involved for one or more reasons such as revenge, redemption, relationships, respect, and rape. Further, these categories themselves greatly overlap.

Bloom begins with a brief overview of what she calls the history of terror, including Robespierre’s systematic use of terror and violence for political goals and Japanese kamikaze pilots during World War II. Focusing within a Western framework, she notes examples of import to major Western powers. In her “logic of oppression” section she clarifies that “without the violent overreaction by the government forces, terrorist groups could not possibly hope to replenish the ranks of lost operatives” (19). Additionally, suicide bombers tend to be “the option of last resort when groups are especially weak” (19). Suicide bombers are the “ultimate smart bomb” as they can adapt targets and strategies on the spot as needed.

In each chapter Bloom looks at a mode of women’s terror activities by examining a particular group and region. In chapter 2 she examines Muslim Chechen operatives against Russia and explores what she calls “The Black Widow Bombers,” women who are active and often suicide bombers. Some may be pregnant. It is unclear their relation to the pop culture Black Widow character originated as a fictive Russian spy in comic books in the 1960s and who was taken by a male reading public as powerful and extremely sexy. The Chechen women agents in Bloom’s case study of the Dubrovka House of Culture hostage crisis in Moscow are presented as second class to the men in the operation. The men held the primary power, made decisions, and likely expected to escape whereas the women were sent in expected to die.

In chapter 3 we find the “Pregnant Bomber” when Bloom presents a case study of the violent arms of the Catholic resistance movement against British occupation in Ireland. These women disguised themselves as pregnant to hide materials and avoid detection from British forces, relying on patriarchal stereotypes of pregnant women as outside the field of political and violent struggle. By this second example we can see that in regions where women have slightly more autonomy in general, women involved in terrorist groups have more “choice” and also options for leadership roles.

Next we are introduced to the case study of “The Scout” among Palestinian Muslims responding to Israeli oppression. As in other cases, here we see the creation of intergenerational networks where those who die for the cause are considered martyrs and children are taught to revere them and their aims as freedom fighters. However, the profile of many Palestinian women involved in violent organizations differs from numerous others. Among the Kurdish Workers Party active in Turkey, and groups in Sri Lanka and Chechnya women suicide bombers comprise a large percent of bombers (40, 25, and 43 respectively) though they play little role in planning operations and are given little training (137). Among Palestinian groups who use violence as a means, Bloom portrays the women as more likely to be highly educated as well as more likely to be involved in strategy and ideological warfare.

Chapters 5 and 6 examine “Future Bombers” in the case study of Black Tiger participants among largely Hindu Tamils in Sri Lanka and the Jemaah Islamiya (JI) who create “Crucial Links” seeking a particular form of a Muslim state in Indonesia and across Southeast Asia. As societies similar to the first case study in Chechnya in terms of gendered power, the women in these examples face more extreme sexist oppression within their home cultures. Their roles in terror networks are to raise and educate warriors, passing nationalist and religious ideology on to the next generation. They are often traded like pawns, married to male operatives to secure familial and stronger relationships between parts of the organizations. Rape and widowhood play significant roles for women suicide bombers in these groups, as in Chechnya, where rape renders a woman beyond society’s bounds. Suicide bombing becomes an option in these cases, where women are all too often sold or kidnapped into terror rings and thus suicide is often seen as a relatively attractive means to redeem oneself. Rape is a constant threat for women under occupation and leaders of terrorist groups rely on this to recruit women who have suffered such violence. Raping women in their own communities is also a strategy of many violent resistance groups as it has proven such an efficient recruiting tool.

The last case study presented analyses Al Qaeda and the growth of global jihadist networks. Here Bloom focuses on the roles of women as “Recruiters and Propagandists.” Still not calling the shots, women have demonstrated, through their use of the internet in particular, that they are effective at spreading the word and drawing more people from across the globe into the fold of extremist groups.

In Bombshell, Bloom provides a clear look at the complex and shifting terrain of women in violent groups across regions and conflicts. She writes in summation: “Gender stereotypes provide part of the explanation; occupation provides another part; religion yet another.” The whole picture of women’s motivations in these acts and groups is “a complicated mix of personal, political, and religious factors that are sparked at different times by different stimuli.” (235) In her theory of “Rs,” Bloom notes that the reason most frequently given for a woman to get involved in terrorist groups is revenge “for the death of a close family member.” Given the ideological contexts in which they live, other women think they need redemption from past sins, usually for sexual liaisons which may have been chosen at an earlier time or forced upon them. Bloom then notes that “the best single predictor that a woman will engage in terrorist violence is her relationship with a known insurgent or jihadi.” She writes: “The relative provides the entrée to the organization and also vouches for her reliability.”(235) In seeking respect within their communities, women “can demonstrate that they are just as dedicated and committee to the cause as men.”(236) Women can become role models in a world, not only their own societies, where the options for women are limited due to sexist oppression.

In varying degrees and in different ways, these four Rs may apply to men. The “plus one” of rape crosses most of the four Rs for women. Bloom notes that “there has been an increase in the sexual exploitation of women in conflicts worldwide.” (236) Bloom tosses the assumption that women are inherently non-violent into the dust bin of history. The question of whether women are coerced or choose violent forms of involvement in their nation’s freedom (or religions’ rein) is far more complex than the media and other studies have depicted. Bloom presents her work as “no more than a prologue to what will be an ongoing chronicle of women and violence” (234) and as such she has done an excellent job. The book makes clear that feminist critical analysis is crucial for understanding and responding to current trends in terrorist groups. Bloom might consider including a U.S. Christian case study in future work as well as a comparison to state propaganda promoting women’s support of militarism and involvement in violent operations.

—

Dr. Marla Brettschneider is Professor of Political Philosophy at the University of New Hampshire with a joint appointment in Political Science and Women’s Studies and serves as Coordinator of Women’s Studies.