The recent appointment of Jean Claude-Juncker as the new President of the European Commission did not go down well with British Prime Minister David Cameron. In leaked comments, Cameron is even said to have warned German Chancellor Angela Merkel that Juncker’s appointment would represent an unacceptable increase in power for the EU’s institutions, which could make a British exit from the EU more likely. Cameron’s warning did not go completely unheeded. He won some concessions, including acknowledgement that the EU’s founding vision of an “ever closer union among the peoples of Europe” might not be for every member state. Despite tense relations with Britain, no member of the EU has indicated that it wants to see Britain leave, although some individuals have made this case.

Nevertheless, with only a few exceptions, there has been very limited discussion of what it could mean for the EU to lose the UK. Nobody is even certain if the EU will face a UK in-out referendum, something that can feel a potentially distant future problem compared to other crises, such as those in the Eurozone and developments in Ukraine. Given Britain’s long-running problems with the EU, including an in-out referendum in 1975, the rest of the EU could also be forgiven for feeling they have been here before, but an actual exit has never come to pass. To be fair, the issue of losing any EU member state is a taboo. It challenges many ideas and theories of European integration.

This presents a problem for the EU. It needs to ask itself whether it is worth making efforts to prevent any exit and, if so, how far these efforts can or should go. If the EU decides it would be better to lose the UK, then what options and limitations would it face in dealing with the UK on the outside, and how do we know that these would outweigh the costs of keeping the UK inside? These are not just questions for the EU. Cameron and those in Britain who seek a renegotiated UK relationship in the EU need to assess whether Britain really is so indispensable that the rest of the EU will make the concessions they want. If Britain leaves, then what type of post-withdrawal relationship follows will also depend, to a large extent, on what the remaining EU is willing to grant. This will depend on how the EU is changed by the loss of the UK.

Mapping Out the Implications for the EU

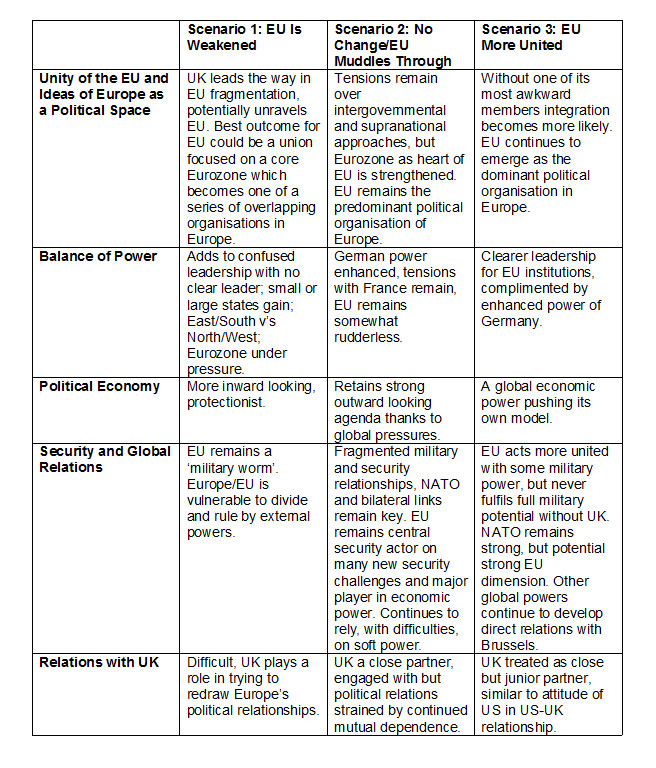

There are five broad areas where the EU might be changed by a Brexit. For each area, three overall scenarios are discussed, scenarios similar to those outlined by Tom Wright in his piece ‘Europe’s Lost Decade’. Scenario 1 imagines a Brexit triggering centrifugal forces that unravel or weaken the EU. Scenario 2 is a largely no-change scenario, with the EU continuing to move forward (or sometimes not at all) as it has done in the past with some muddling through in the face of a Brexit. Scenario 3 portrays a Brexit leading to more integration in the EU. The aim here is not to assess which of the scenarios is the most likely, although some passing assessment is inevitable. In the limited space available, the aim is instead to briefly map out a range of possible implications for the EU.

- Unity of the EU and Its Place in Europe

Worries that granting Britain a renegotiated relationship in the EU will lead to its unravelling, because it could lead to an EU ‘à la carte’, have to be compared with worries that a UK exit could set an example that challenges the direction of European integration that other states then follow. Whether this happens depends on how the UK performs outside the EU. It is also likely to depend on how a Brexit impacts on Germany, the EU’s driver, paymaster, and indispensable nation. In his analysis of European disintegration theories, Webber argues the EU has never faced a crisis made in Germany. A Brexit that combined with such a crisis could lead to an EU reduced to a core of Eurozone members that form one of a series of overlapping organisations managing European relations. Alternatively, rid of ‘an awkward partner’, the EU could become more united. The Eurozone and the EU would more neatly align allowing for more integration. Instead of hitting Germany, a Brexit could strengthen Berlin’s position and German support for more integration. However, the Eurozone’s problems demonstrate how, even with the UK out of the room, the EU has struggled to find the necessary unity to manage common problems. This problem would be even clearer in any muddling-through scenario, which would see the EU continue to cope with, but not solve, its underlying problems.

- Balance of Power

Britain’s departure could upset complex relations between north and south, east and west, small and large members, liberal free-trading states and ones more inclined to protectionism. Franco–German relations, often considered the motor of European integration, have often used the UK to balance the other. The EU’s institutions would lose their British influences, with the EU having to renegotiate QMV, national quotas, and make up for the loss of the UK’s budget contribution (€4,703.4 million in 2011). The outcome could be a more confused, divided, and weakened EU. Alternatively, as noted above, Germany’s position could be strengthened, enhancing German support for further integration, and strengthening the Eurozone and EU institutions. However, a muddling-through scenario would see Germany remain ambivalent about leading or further developing the EU, with other states, such as France, also being weary of any growing power in Brussels.

- Political Economy

Any survey of views by other states into what a Brexit might mean reveals concerns about economic costs. The UK constitutes 14.8% of the EU’s economic area, with 12.5% of its population. It represents 19.4% of EU exports (excluding intra-EU trade) and within the EU runs a trade deficit £28 billion a year (2011 figures). Many proposals for a post-withdrawal relationship focus on maintaining close economic relations. But it is not just trading figures that are of concern. Losing Britain’s ‘Anglo-Saxon’ economic influence with its strong support for free trade could lead to an inward-looking, protectionist EU. However, we must ask whether countries such as Germany or even France could allow the EU to become more inward-looking and protectionist. Even the European Commission, often lambasted by British Eurosceptics as a bastion of state-socialism, is also often seen as pursuing a neoliberal trade agenda. Pressure from the USA or China, and international trade negotiations, may mean the EU must continue to embrace an outward-looking economic agenda. Granted, models of state-capitalism in Russia or China may grow in appeal. Should the EU integrate further and feel more confident, then it may begin to espouse its own model for managing globalisation.

- Security and Global Relations

Britain, along with France, has been crucial to many of the EU’s efforts to work together on foreign, security, and defence policies. Losing Britain could undermine such efforts, potentially further weakening much sought for – especially by the USA – efforts to strengthen the European side of NATO, whether this be in defence business cooperation or in taking a more robust line with Russia. The outcome could be a UK that emerges as one of the poles of a multipolar Europe. This could make more likely a scenario, outlined by Jan Techau, of a Europe that ‘is not a pillar of world affairs but a territory that risks being pulled asunder between the United States and Asia’. But Britain’s central role in this area has also not been entirely constructive. Fears about sovereignty and jeopardising NATO have constrained UK commitment. Removing the UK could free such an obstruction. We should remember that the EU’s international relations – whether in military or soft power – are varied and widespread. However, once again, should the EU without the UK act more coherently, then it could develop as a more robust European arm of NATO or, as some fear, an alternative to it. The rest of the world would also continue to develop direct relations with Brussels.

- Relations with the UK

Both the UK and EU will be compelled by geography, economics, law, demographic links – indeed, by sheer realpolitik – to develop a working relationship for managing common problems. A variety of proposals exist, ranging from special trade deals through to membership of EFTA and/or the EEA. What would be the best deal for the EU is rarely assessed, despite the EU also having to agree to it. What the EU agrees to will depend on what is in the interests of the remaining EU, which will be shaped by whatever the outlook is of a post-Brexit EU. The UK may attempt to use its new position to redraw the economic and political relationships of Europe, moving away from the more supranational political relationships of the EU towards more intergovernmental arrangements focusing on trading links. The UK may also expect to be treated in some special way to reflect that, while it might no longer be an EU power, it remains a powerful European power that by 2050 could have a population and economy bigger than any EU member. While it will move from decision maker to decision shaper, it will also be one of the best placed to shape decisions bilaterally, multilaterally, through civil society, business, or other avenues. The biggest test for the EU will be in whether it can present a united front to the UK or manage relations through forums such as an EU+1 arrangement, an EU2+1 involving France, Germany, and the UK, or a modified version of the EU’s current G6. However, should the EU become more united, its attitude to the UK might mirror that of the USA: a one-sided ‘special relationship’.

Conclusion

This is a first and very truncated attempt to flesh out how the EU might develop in the face of a Brexit. It builds on research undertaken at the SWP and from an ongoing 26-nation project with the DGAP. The topic, like European disintegration in general, remains under-researched.

As is clear from the scenarios, summarised in a table below, this is not necessarily about disintegration. A Brexit may not prevent, or alter, the direction of European integration for large areas of Europe. Whether or how the EU develops will depend on factors such as the politics of the various member states and the economic performance of the Eurozone. Britain’s behaviour will be one part of this.

Nevertheless, a Brexit would pose questions about understanding European integration and policy questions about how the rest of the EU should respond to the UK. Could the EU face a choice between prioritising interests, such as trading links over values such as that of ‘ever closer union’, and, if so, which should it take? And who will decide and how? Is this a matter for only the largest member states, such as Germany, or would a Brexit require the rest of the EU to seek some new settlement, perhaps adding to pressure for a new treaty?

Finally, the amount of leverage the threat of Brexit has for the UK depends not so much on what the UK contributes to the EU in terms of trade balances, economic outlooks, or military units. It is more about how valued that contribution is by the rest of the EU. The UK’s antagonistic behaviour may be weakening that leverage. Traditional allies, such as Poland and Denmark, have begun to look away from the UK, seeing it as more of a spoiler in the EU than a constructive partner. With a Brexit likely to take several years to emerge, it may be that by the time it happens, the rest of the EU would have moved into a position where losing the UK is not the big shock some in the UK think it will be.

Scenarios of How a Brexit Might Change the EU

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Brexit Britain in the Transatlantic Standoff: Bridging the Gap?

- Post-Brexit EU Defence Policy: Is Germany Leading towards a European Army?

- The UK’s Global Role Post-Brexit: What is Worth Researching?

- An ‘Expert’ Perspective on Brexit… Means Brexit

- Lingering Effects of the UK’s Brexit Role Change

- The British Labour Party after Brexit