By now the acronym “BRICS” – referring to Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa –has become a buzzword in international politics and is frequently used in connection with projections on the future of the international order. The term BRICs (by that time without South Africa) was first coined by the investment bank Goldman Sachs in 2001, depicting at that point a group of large, fast growing and thus promising economies (O’Neill, 2001). The continuing global economic transformation in favor of the BRICs quickly led to the originally purely financial term becoming a fact also in international politics (Stuenkel, 2013, 614)[1]. In 2006, initiated by Russia, the BRICs started transforming into a political grouping with their foreign ministers gathering informally at meetings of International Organizations and announcing regular meetings to examine the main issues on the global agenda. In April 2009, at Russia’s invitation, the BRICs held their first leaders’ summit in Yekatarinburg. South Africa was formally invited to join the club in late 2010, thereby turning the BRICs into the BRICS with a capital S (Armijo & Roberts, 2014, 04). Since then, the BRICS hold regular meetings on different government levels and issues to allegedly improve coordination “on international and regional issues of common interests” (BRICS, 2011).

And indeed, recent years have brought some visible coordination among the BRICS[2]. For instance, in 2011 and 2012 (then minus Brazil) the BRICS served simultaneously on the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) and showed a notably high level of voting coincidence. In December 2011, BRICS trade ministers agreed on common principles in WTO negotiations (Brütsch & Papa, 2013, 300). On their summit in 2014, the BRICS decided to establish the so called New Development Bank (BRICS, 2014). Such circumstances have lead many, including journalists, politicians and political scientists, to portray the BRICS as a powerful coalition threatening the US-led liberal world order as we currently know it (Armijo, 2007, 27; Armijo & Roberts, 2014, 503).

However, at the same time the BRICS show some pervasive differences as well as signs of disagreement and competition among themselves. They vary in their cultural and religious traditions, their historical trajectories as well as their domestic political systems with Brazil, India and South Africa being formal democracies and Russia and China being more authoritarian governments (Armijo, 2007, 8). Also, their economies are structured differently. While China is specialized in manufacturing, India is specialized in services, Russia and South Africa in commodities and Brazil in agriculture. The last three are large commodity exporters, while China is a commodity importer (Stuenkel, 2013, 620). Furthermore, trade disputes have been common among the BRICs (Cameron, 2011, 3f) and the IBSA states (India, Brazil and South Africa) have all expressed their disenchantment with China’s economic and fiscal policies (Pant, 2013, 98). What is more, China, India and Russia all compete for influence and resources in central Asia (Brütsch & Papa, 2013, 301) in addition to the continuing historical distrust and rivalry between India and China as well as China and Russia (Laïdi, 2012, 615). Such differences and disparities among the BRICS have prompted some to call the BRICS an acronym with no substance and to question its usefulness as an analytic category. They conclude that these states have little more in common than high economic growth and large size (Armijo, 2007; Käkönen, 2013; Sparks, 2013).

However, in order to actually pose a threat to the current international order as argued mainly by realists, a certain degree of cohesion as a group based on common foreign policy preferences and trust is essential (Pape, 2005, 16). Yet, surprisingly few studies analyzing the potential impact of the BRICS on the international system evaluate whether these states in fact meet this crucial condition. To tackle this academic void, this analysis therefore seeks to answer the following research question: Are the BRICS a group with coherent foreign policy preferences? In other words: Are the BRICS just rhetoric or a reality?

The focus of this paper is on the BRICS rather than on another coalition of emerging powers such as IBSA, since the former, including two permanent members of the UNSC, three nuclear and two non-democratic powers, has the greatest political recognition. In addition, the BRICS have been one of China’s favorite forums, a relevant factor considering its economic weight (Laïdi, 2012, 5). This study bears scientific as well as policy relevance. It is imperative to answer the research question posed here, as only if the BRICS indeed are a group with coherent foreign policy preferences are scientific predictions on the potential threat to the current international order posed by the BRICS meaningful and corresponding policy strategies necessary. While other studies on this topic rely on voting similarity indices to measure foreign policy preferences, which have certain shortcomings, this paper analyses the research question using a new and more precise data set on states’ United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) voting behavior introduced by Bailey, Strezhnev and Voeten (2015).

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. After presenting the relevant literature on the topic, it will be elaborated based on neo-realism why coalition building by the BRICS is presumable. In the fourth section, the new data set and the pertaining estimation model by Bailey et al. (2015) are presented before the BRICS’ foreign policy coherence is evaluated and concluding remarks are given.

The BRICS have attracted quite some academic research and in recent years two main strands of literature have emerged. While the first examines individual states’ motives and strategies within the BRICS, the second analyzes the potential revisionist threat the BRICS pose to the current international order (Brütsch & Papa, 2013, 303f). Most of the literature however, by ascribing the BRICS the potential to impact the international order, from the outset take them to be a coherent group without further testing this assumption.

Few academic publications actually examine the cohesion of the BRICS with regard to their foreign policy positions. It is quite striking that those authors that do so come to the conclusion that the BRICS are not quite as cohesive as the majority of BRICS-related studies assume without testing. Armijo (2007) examines the analytical category “BRICs” under the light of three theoretical perspectives (neoclassical economics, realism and liberal institutionalism) and concludes that while being a potential phenomenon within realism, the fear of the BRICs is unjustified. Within liberal institutionalism the concept is somewhat convincing, however not in its entirety, but with a cleavage between democracies and autocracies. Analyzing two case studies Brütsch and Papa (2013) argue that the BRICS lack a coherent strategy and thus their coalitional cohesion is no more than tentative. Cameron comes to the conclusion that due to their internal competition and differences between them the BRICs are “not a cohesive grouping in major political, security, economic or trade issues” (2011, 2). Pant equally states that the narrative surrounding the BRICS is “exaggerated” and that they “remain an artificial construct”, mainly owed to their problems of good governance, socioeconomic inequality and declining growth rates (2013, 103). In his analysis focusing on the BRICS’ media landscape, Sparks (2014) argues that in politics, economics and media there is hardly any dimension in which these countries are uniform and collectively distinct from other developing countries. Assuming the BRICS form a strong defensive coalition Laïdi (2012) reasons that they however remain weak on the offensive side due to their pursuit of national interests and being guided by mutual mistrust.

In sum, these studies doubt the coherence of the BRICS as a result of the differences, competition and distrust existent among the respective states, basing their analyses mainly on case studies and historical evidence. To the author’s knowledge there are only few publications analyzing the question of BRICS cohesion in a systematic, quantitative way. Ferdinand (2014a) shows growing foreign policy convergence among the BRICS by analyzing their UNGA voting data from 1974 to 2011. He finds that BRICS cohesion is much greater and sustained than that of the Permanent Five (P5) but lower than that of IBSA. However, the establishment of the annual BRICS summits in 2009 did not lead to greater cohesion among the group (Ferdinand, 2014a, 383). Hooijmaaijers, analyzing BRICs UNGA voting cohesion between 2006 and 2009, finds no systematic increase of voting cohesion and concludes that cooperation between the four states is lose at best (Hooijmaaijers, 2011, 9). Both, Ferdinand’s (2014a) and Hooijmaaijers’ (2011) studies use UNGA similarity indices for their analyses, which have a number of shortcomings. Also, their papers are quite unambitious with respect to theoretic foundations. In contrast, this paper relies on theoretical assumptions to generate expectations that are evaluated with the help of theoretically based estimation methods.

Neo-Realist Soft Balancing Coalitions

The acronym BRICS originally depicted financial and economic aspects only. In addition, as was shown above, the BRICS have many differences among them. So why should they of all states form a group with coherent foreign policy preferences? After comparing different theoretical explanations, Armijo (2007) concludes that realism provides explicatory power to a coalition forming behavior among BRICS. In addition, Hurrel (2006) and Skak (2011) argue that certain recent actions by the BRICS can indeed be interpreted as soft balancing like realism predicts. Furthermore, most of the literature invoking a threat posed by the BRICS does so from a realist perspective. For this reason, realism, more specifically neo-realism’s rather recent strand of soft balancing theory, is applied here.

In its traditional reading, neo-realism (more precisely its Balance of Power Theory) predicts that in a unipolar system one or more states with capabilities matching those of the superpower will balance the latter (Paul, 2005, 49) either internally (via the build-up of military power) or externally (through the creation of military alliances) (Pape, 2005, 15). This behavior applies particularly to states growing wealthier, as this leads them to seeking greater world-wide political influence and to being more capable of expanding their interests (Schweller, 1999, 2ff). However, since the end of the Cold War Balance of Power Theory does not adequately explain great power behavior (Paul, 2005, 58). Pape argues that there is a lack of traditional, hard balancing by major powers since in a unipolar system, by definition, no state is capable of challenging the leader individually. Rather, balancing can only occur by multiple states acting together in a counter-hegemonic coalition. However, forming such a coalition poses a considerable risk in face of coordination problems. Hard balancing is thus being delayed until a group of major powers with common foreign policy preferences has managed to credibly coordinate their action. Soft balancing, i.e. “nonmilitary tools to delay, frustrate, and undermine” the hegemon using international institutions, economic statecraft and diplomatic arrangements (Pape, 2005, 10), is a viable strategy to this end (Pape, 2005, 16ff). Institutional soft balancing strategies such as the formation of diplomatic coalitions can help to develop a convergence of expectations and establish a basis of trustful cooperation to effectively overcome problems of collective action (Pape, 2005, 17). Realists, in particular neo-realist soft balancing theory, thus expect states with increasing economic prosperity to form a soft balancing coalition with the goal of overcoming coordination problems between them to build the capacity for challenging a sole superpower.

Applying this neo-realist perspective to the case at hand generates the following expectations: The BRICS are all characterized by increasing economic prosperity, in a degree that qualifies them as major powers now or in the nearest future (Armijo, 2007, 25).This urges them to balancing behavior against the US. However, to be able to form a counter-hegemonic coalition necessary to challenge the current liberal international order led by the overly powerful US, some coherence in foreign policy preferences among them is essential. The BRICS can change the current international order or increase their voice in the existing one only as an institution with a certain degree of trust and shared preferences (Käkönen, 2013, 3; 5). Only with a set of common values and a reduction in intra-coalitional frictions are they capable of collective action and the development of a common agenda (Armijo & Roberts, 2014, 519; Brütsch and Papa, 2012, 5). Recent increases in the intensity of BRICS cooperation indicate those states’ determination to form a coalition and thus a forum to enhance mutual values, interests and trust. However, in contrast to earlier studies, this paper seeks to evaluate whether this impression bears systematic evaluation or is merely due to symbolic politics.

Foreign policy preferences and thus the BRICS’ foreign policy convergence are measured in this paper with their voting behavior in the UNGA. For years, scholars have used votes cast in the UNGA to measure foreign policy preferences, since the UN offer the closest approximation to the international community (Chan, 2008, 34). They are apt for such analyses due to the sheer number of states involved and votes cast as well as to the wide variety of issues dealt with by the UNGA which is fairly representative for the global agenda (Voeten, 2004, 735). With respect to the BRICS, UNGA voting is informative as they strive for an enhanced role for the UN and for themselves in it (Ferdinand, 2014a, 378f). This and the fact that UNGA voting is usually legally non-binding, decreases the probability of strategic voting so that votes can be assumed to reveal real BRICS preferences (Bailey et al., 2015, 7). In addition, the relevant concept of interest concerns global political issues, which is a precondition for the use of UNGA votes to be appropriate (Voeten, 2013).

Most UNGA-based preference measures are based on dyadic similarity of vote choices, with Signorino and Ritter’s (1999) S-score being the most widely used index. Similarity indices are treated as interval-level measures and assume a straight-forward relationship between how often two states vote together and the similarity of their preferences. By ignoring methodological advances in the roll-call literature[3], this approach fails to separate changes in state preferences from changes in the content of votes. As such, agenda shifts from one year to the other can result in a change in voting similarities between two states even though neither state actually changes its interest. Consequently, such indices are inappropriate for studies focused on preference changes in time series cross-sectional analyses (Voeten, 2013).

In contrast to earlier work on the BRICS (see literature above) or other emerging powers (Ferdinand, 2014b; Graham, 2011; Holslag, 2011), which use the “conventional” indices, this paper will therefore seek to answer the above question with the help of new data introduced by Bailey et al. (2015)[4]. It relies on an explicit theoretical model (dynamic ordinal spatial model), stipulating how states translate their ideal points along an unobserved continuum into observed choices. Thereby unobserved preferences can be more accurately inferred from observable voting choices than with similarity indices (Bailey et al., 2015, 2; Voeten, 2004, 731).

Bailey et al. (2015) estimate national ideal points for each state and UN session on a single dimension reflecting the current liberal world order. A country’s vote on a given resolution is then a function of its ideal point, characteristics of the vote and random error. Resolutions identical across years are used to serve as bridge observations so that preference estimates are comparable over time. As a consequence, the model factors in changes in agenda rather than simply assuming all changes in voting similarity reflect preference changes as similarity indices do. In other words, the fact that changes in voting coincidence can stem from the characteristics of the resolutions on the agenda in a particular year, i.e. multiple votes on a specific crisis, rather than changed policy positions is accounted for by this model. Leaving them unaccounted for, annual dyadic similarity measures can be strongly biased by such agenda changes (Voeten, 2013). The resulting data can therefore better separate signal from noise in identifying foreign policy preference shifts than other UNGA indices. In addition, being less sensitive to shifts in the UN’s agenda, it allows for more valid inter-temporal, especially long-term, comparisons. Overall, ideal points show greater validity than similarity indices (Bailey et al., 2015).

The empirical analysis covers the period from the UNGA’s first session in 1946 until its 69th session in 2014. This relatively long period of time studied renders possible observing enduring patterns and significant changes. China enters the analysis in 1971 when it was admitted to the UNGA, South Africa in 2011, after it had become a member of the BRICS.

Only about three quarters of all UNGA resolutions are adopted with a vote and thus included in this analysis (Bailey et al., 2015, 8). In the period between 1946 and 2014 5352 issues were put to vote, with 20447 votes cast by the BRICS. When votes are taken, the BRICS vote mostly in favor, as can be seen in Table 1[5], which summarizes their voting records.

| Table 1. Voting Records of BRICS in UNGA 1946 – 2014 (Percentage of Voting Choices). | ||||||

| China | India | Russia | Brazil | South Africa | BRICS | |

| Yes | 78.77 | 78.85 | 69.58 | 80.33 | 87.59 | 76.91 |

| No | 3.25 | 7.21 | 14.26 | 6.69 | 0.73 | 8.04 |

| Abstention | 8.31 | 13.15 | 15.41 | 11.96 | 9.49 | 12.41 |

| Absent | 9.67 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 1.03 | 2.19 | 2.65 |

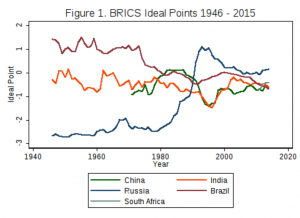

To analyze whether the BRICS are a coherent group with common policy interests, the evolution of the five countries’ ideal points over time was examined. Figure 1 displays their individual ideal points since 1946. It can be seen that overall BRICs preferences have indeed notably converged in between the end of the Second World War and the fall of the Berlin Wall in late 1989. At the end of the Cold War the BRICs shared almost the same ideal point. Their preferences again diverged thereafter, but started converging again by the mid-1990s.

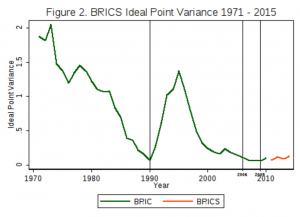

To more systematically and precisely being able to grasp the results obtained by the visual inspection, the intra-group variance of ideal points was calculated for several relevant points in time. In addition, Figure 2 shows the variance graphically over the time period from 1971, when China entered the UNGA, to 2014. Higher variance among the BRICS implies lower coherence, while, vice versa, lower variance stands for higher coherence.

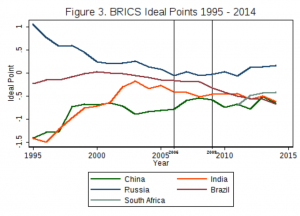

The impression obtained by the graphical inspection is confirmed here: Variance decreased, and thus coherence increased, almost steadily in between 1946 and 1990 (with a minimal variance of 0.07 in 1990), before the BRICs diverged again in the 1990s (with a maximum of ideal point variance of 1.37 in 1995). Since 1995 variance decreased again, meaning that policy preferences converged, nearly continually. In 2006, when the BRICs held their first informal ministerial meeting, variance was at 0.1 and further fell to a value of 0.06 in 2009, hence below the minimum of 1990. However, since 2009 there has been another slight increase in variance up to a value of 0.12 in 2014. As can be seen in Figure 3, which takes a closer look at recent BRICS ideal point developments, this divergence is mainly due to the development of Russia’s ideal point. After over a decade of convergence, Russia has ceased approaching the rest of the BRICS, which are jointly taking on lower ideal point values in recent years[6].

This paper set out to examine whether the BRICS, a group of emerging states often portrayed as a threat to the current world order, do even fulfill a main precondition to being a potential challenger – namely whether they are a coherent group with common foreign policy preferences. The analysis of BRICS ideal points based on UNGA voting data from 1946 to 2014 confirms that indeed there has been a long-term policy convergence among the respective countries. The divergence in the early 1990s can presumably be attributed to the collapse of the USSR and the abrupt redirection of Russian foreign policy towards the West, at least in the early Yeltsin years (Ferdinand, 2014a, 383). Furthermore, the data show that the continuing institutionalization of the BRICS starting in 2006 with their first ministerial meeting did not have a significant impact on their preference convergence. Rather, there was a continuation of a trend of cohesion that had been ongoing since 1995. Surprisingly though, there has been a slight renewed divergence since 2009, when the BRICs held their first leaders’ summit, which has carried on until today[7]. This is surprising especially since Russia frequently attaches particularly great importance to the BRICS compared to the other members (Roberts, 2009). However, the divergence of Russia away from the rest is not yet drastic and it remains to be seen whether it has serious implications for the BRICS as a cohesive group. These results correspond with Ferdinand’s (2014a) insofar as he also finds a considerable degree of cohesion among the BRICS that has not been changed by their institutionalization. Contrasting, it differs from Hooijmaaijers (2011) and from the authors assessing the topic in a qualitative manner (see above) who find no BRICs coherence.

However, one has to keep in mind the limitations of this study. Some pertain to the usage of UNGA voting data to measure preference cohesion. Even though the application of ideal points has several advantages over the frequently used similarity indices, they still bear some shortcomings. First, voting may be a function not only of preferences but of other factors not accounted for (Bailey et al., 2015, 7). Strategic voting might take place especially on votes important to the US, so future analyses should examine such votes separately[8]. Also, estimating separate ideal points for different categories of votes, such as votes concerning nuclear or human rights issues as proposed by Ferdinand (2014a), could generate some insight here. Second, ideal point estimation makes rather strong assumptions about voting behavior and characteristics of the vote. It can be questioned and should therefore be further tested, whether they hold for UNGA voting. Third, one problem with inductive scaling methods is that the content of the dimension measured is not unambiguously interpretable. However, Bailey and his colleagues (2015) have put quite some effort in the substantive interpretation of the dimension, which is acceptance of the liberal world order in this case. Finally, the UNGA does usually not deal with purely economic or monetary issues and issues that have appeared on the UNSC (Voeten, 2004, 735). However, particularly in the early years of their institutionalization, i.e. 2006 and subsequent years, the BRICs were mainly concerned with international finance (Stuenkel, 2013). As a consequence, UNGA data might not display the actual level of coherence among BRICs in those years.

Another potential limitation is that while this inductive analysis can show a pattern of voting convergence, it cannot reveal what the BRICS’ motives of convergence are. While it might be part of their balancing ambitions, there are other potential reasons, such as economic interest or regional security concerns. However, such differing explanations do not necessarily exclude each other. They could also be seen as complementary and synergistic (Flemes, 2009, 407). In addition, coherent UNGA voting behavior by the BRICS cannot only be interpreted as a cohesion of foreign policy, but can also be seen as a institutional soft balancing strategy in itself (Paul, 2005, 58), which gives the soft balancing theory further appeal here.

Despite the slight recent increase in divergence, currently the variance among the BRICS is at a sufficiently low level to argue that they form a coherent group. This result thus contrasts those publications emphasizing the differences among the BRICS and for this reason questioning them being a meaningful group. Rather, it provides an empirical and systematic basis for those authors focusing on the potential impact the BRICS can have on the world order. Due to the advantages of ideal point data, future studies should assess whether the BRICS are a group of dissatisfied, revolutionary states, intent on challenging the current liberal order by evaluating the distances between US and BRICS’ ideal points over time. The data on dyadic ideal point distances provided online by Voeten and his colleagues could be helpful here (Bailey et al., 2015).

Without doubt there are given differences and disagreements among the BRICS. However, it cannot be denied that internal differences exist in all interstate groupings, including NATO or the EU. What is more, this analysis has shown a relatively high degree of foreign policy preference cohesion among the BRICS. It therefore argues that the BRICS indeed should be taken serious as a group. They are not merely rhetoric – they are a reality.

References

Armijo, L. E. (2007). The BRICS Countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) as an Analytical Category: Mirage or Insight? Asian Perspective, 31(4), 7–42.

Armijo, L. E., & Roberts, C. (2014). The Emerging Powers and Global Governance: Why the BRICS Matter. In R. E. Looney (Ed.), Routledge International Handbooks. Handbook of emerging economies (pp. 503–524).

Bailey, M. A., Strezhnev, A., & Voeten, E. (2015). Estimating Dynamic State Preferences from United Nations Voting Data. Journal of Conflict Resolution, Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/0022002715595700.

BRICS (2011). Sanya Declaration. Hainan, China.

BRICS (2014). Fortaleza Declaration. Fortaleza, Brazil.

Brütsch, C., & Papa, M. (2013). Deconstructing the BRICS: Bargaining Coalition, Imagined Community, or Geopolitical Fad? The Chinese Journal of International Politics, 6(3), 299–327.

Cameron, F. (2011). The EU and the BRICs, Policy Paper No. 3, Jean Monnet Multilateral Research Network on ‘The Diplomatic System of the European Union’.

Chan, S. (2008). China, the US and power-transition theory: A critique. London, New York, NY: Routledge.

Ferdinand, P. (2014a). Rising powers at the UN: an analysis of the voting behaviour of brics in the General Assembly. Third World Quarterly, 35(3), 376–391.

Ferdinand, P. (2014b). Foreign Policy Convergence in Pacific Asia: The Evidence from Voting in the UN General Assembly. The British Journal of Politics & International Relations, 16(4), 662–679.

Flemes, D. (2011). India-Brazil-South Africa (IBSA) in the New Global Order: Interests, Strategies and Values of the Emerging Coalition. International Studies, 46(4), 401–421.

Graham, S. (2011). South Africa’s UN General Assembly Voting Record from 2003 to 2008: Comparing India, Brazil and South Africa. Politikon, 38(3), 409–432.

Holslag, J. (2011). The Elusive Axis: Assessing the EU-China Strategic Partnership. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 49(2), 293–313.

Hooijmaaijers, B. (2011). The BRICs at the UN General Assembly and the Consequences for EU Diplomacy, Policy Paper No. 6, Jean Monnet Multilateral Research Network on ‘The Diplomatic System of the European Union’.

Hurrell, A. (2006). Hegemony, liberalism and global order: what space for would-be great powers? International Affairs, 82(1), 1–19.

Käkönen, J. (2013). BRICS as a New Constellation in International Relations? Paper prepared for the IAMCR 2013 Conference Dublin, June 25 to 29, 2013.

Laïdi, Z. (2012). BRICS: Sovereignty power and weakness. International Politics, 49(5), 614–632.

Looney, R. E. (Ed.) (2014). Routledge International Handbooks. Handbook of emerging economies, New York, NY.

O’Neill, J. (2001). Building Better Global Economic BRICs. Global Economics, (66).

Pant, H. V. (2013). The BRICS Fallacy. The Washington Quarterly, 36(3), 91–105.

Pape, R. A. (2005). Soft Balancing against the United States. International Security, 30(1), 7–45.

Paul, T. V. (2005). Soft Balancing in the Age of U.S. Primacy. International Security, 30(1), 46–71.

Reinalda, B. (Ed.) (2013). Routledge Handbooks. Routledge Handbook of International Organization. New York, NY.

Roberts, C. (2009). Russia’s BRICs Diplomacy: Rising Outsider with Dreams of an Insider. Polity, 42(1), 38–73.

Schweller, R. L. (2014). China’s Aspirations and the Clash of Nationalisms in East Asia: A Neoclassical Realist Examination. International Journal of Korean Unification Studies, 23(2), 1–40.

Signorino, C. S., & Ritter, J. M. (1999). Tau-b or Not Tau-b: Measuring the Similarity of Foreign Policy Positions. International Studies Quarterly, 43(1), 115–144.

Skak, M. (2011). The BRIC Powers as Actors in World Affairs: Soft Balancing or … ? Paper presented at the IPSA-ECPR Joint Conference, Sao Paulo, February 16 to 19, 2011.

Sparks, C. (2014). Deconstructing the BRICS. International Journal of Communication, 8, 392–418.

Stuenkel, O. (2013). The Financial Crisis, Contested Legitimacy, and the Genesis of Intra-BRICS Cooperation. Global Governance, 19, 611–630.

Voeten, E. (2004). Resisting the Lonely Superpower: Responses of States in the United Nations to U.S. Dominance. The Journal of Politics, 66(03).

Voeten, E. (2013). Data and Analyses of Voting in the UN General Assembly. In B. Reinalda (Ed.), Routledge Handbooks. Routledge Handbook of International Organization (pp. 54–66).

Endnotes

[1] For a number of fairly up-to-date statistics on the BRICS economic power compared to the US and other major countries see Armijo and Roberts (2014). For an even more detailed presentation see Armijo (2007).

[2] In this paper, for general statements the term BRICS is used. Only if statements refer particularly to the group excluding South Africa, is the acronym BRICs used.

[3] Like Poole and Rosenthal’s (1997) NOMINATE, a scaling procedure based on a probabilistic spatial model of voting, which is frequently used to assess voting behavior in national parliaments.

[4] The full data set is available online at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml;jsessionid=650f2355441b81b5f162a8e625ed?persistentId=hdl%3A1902.1/12379&version=7.0 [accessed July 18, 2015].

[5] Data for Table 1 were taken from Voeten (2013).

[6] It is quite interesting to note the striking recent preference similarity among the IBSA states.

[7] With a small dip in 2011, which is probably due to the joining of South Africa in that same year.

[8] US important votes are declared annually in the US State Department’s “Voting Practices in the United Nations” report.

Written by: Laura Peitz

Written at: University of Potsdam

Written for: Dr Matthew Stephen

Date written: August 2015

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Reform of the Global Financial Architecture: The Role of BRICS and the G20

- The BRICS Bloc: A Pound-for-Pound Challenger to Western Dominance?

- Revisiting Cold War Rhetoric: Implications of North Korean Strategic Culture

- Beyond the Humanitarian Rhetoric of Migrant Information Campaigns

- Imperialism in Contemporary Russian Liberalism: Alexei Navalny’s Rhetoric

- China’s Instrument or Europe’s Influence? Safeguard Policies in the AIIB