War art is a practice of international security. Painting war is not just an exercise in aesthetics, but an ethical position. In war art, aesthetics and ethics are indiscernibly linked. War art has historically asserted established and emerging international power relations; provided testimonies and interpretations by those who witnessed war; functioned as a bastion to protest against war; made invisible subject positions visible; been used as propaganda tool by governments and as a way to make citizens empathise with the causes of war. War art is a battleground, as much as warzones are. Joanna Bourke (2017: 22) has recently commented that ‘[w]ar licenses the militarization of art.’ And, indeed, we could add that war licences the militarisation of the artist’s body and mind. Some artists are commissioned by war memorial, thus becoming ‘official’ war artists, while others go to warzones independently to witness, unconstrained, war. Others yet engage with war from afar, using their imagination, or focusing on the home-front. The representations and subjectivities produced through war art intersect, reproduce, or contest discourses of war.

As a battleground of war, war art raises important ethical questions about the aestheticisation of violence and the anaesthetisation of publics. In this intervention, I explore the question that every artist interested in war has to grapple with: How can artists represent war without reproducing it, without making war into a beautified spectacle for public consumption devoid of critique, and without militarising their body, work, and art? I suggest that the answer to this question is a fine balancing between embodiment and disembodiment, that is, the exposure of certain bodies, and the concealing of others, the militarisation of certain experiences for the demilitarisation of others. Militarisation and demilitarisation, and embodiment and disembodiment are not zero-sum games.

I elaborate this suggestion with reference to Australian artist Kathryn Brimblecombe-Fox, who has produced a series of paintings, gouache and watercolour on paper, which engage critically with drone warfare and the attendant system of surveillance. The series is titled Dronescapes. Most of the artworks can be viewed on the artist’s blog available at https://kathrynbrimblecombeart.blogspot.com.au/, which also offers insightful posts about the artworks, the process of creating them, as well as about the practices of drone warfare. The reflections which follow have been drawn from an attentive examination of the paintings and the blog, and from extensive conversations with the artist.

Drone warfare is a hidden war, not only because drone operations and killings, especially so-called ‘collateral damage’ of mistaken targets, are underreported in news media, but also because drones can loiter in the sky without being seen. Furthermore, drone warfare is hybrid to the extent that it merges military and civilian spaces in new ambitious ways, and ambiguous to the extent that the deployment of drones is for surveillance as much as for targeted killing. Surveillance and killing are not necessarily consequential, but are certainly intrinsically related. Drone operators are defence personnel residing, often times, in civilian centres in the global north, whose job is to collect data about individuals who might potentially be targeted for killing (Grayson, 2012; Holmqvist, 2013; Wilcox, 2015). Drones make warfare look surgical, clean, and as if there is nothing to see (Gregory, 2012). Against this backdrop, Brimblecombe-Fox has realised that it is paramount to represent and uncover drone warfare in ways that reveal the invisible. Yet, not many public artists are in the business of doing so.

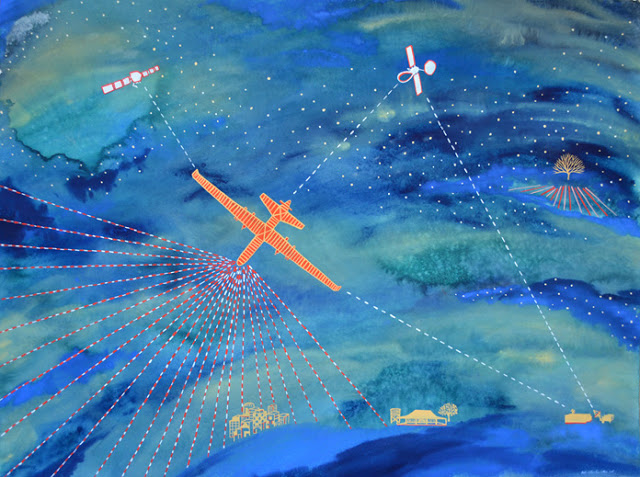

Militarised drones do not fly over Australian skies. But it did not take long for Brimblecombe-Fox to realise that while these types of drones are physically distant from her and Australians, we are all implicated in drone warfare. Her painting Not a Game speaks to that. It shows a drone linked to satellites and a control station, which is represented near civilian centres. The links are made visible in the painting through uncanny lines which reveal the drone’s connectivity to dual-use military/civilian technological infrastructure. While the drone is depicted surveilling and collecting data, it is armed with missiles. The drone is ready to transform targeted surveillance into targeted killing at any time. The radiating lines emanating from the drone are depicted with two different colours, exposing the drone’s wide area surveillance signals as well as potential targeting signals.

While Brimblecombe-Fox does not have the experience of living in a country where military drones colonise skies, her work stems from the realisation that her experience, like that of all of us connected to the digital world, is ‘droned’, that is, it is recorded, repackaged, and fed back to us through personalised algorithms (Andrejevic, 2015). Furthermore, military drone operations rely on knowing the human body, or on what Marlin-Bennett (2013: 602) calls ‘embodied information’, ‘the information contained in the body that can potentially be accessed by others through an act of power.’ As drone warfare increasingly institutionalises individual targeting, for both surveillance and killing, the military has come to rely on big data systems and techniques to identify and target ‘personality strikes’, that is, the targeting of individuals whose patterns of life are associated with being a terrorist (Wilcox, 2017: 16). When the identity of the target is unknown, and its targeting stems not from human intelligence but from suspected abnormal patterns of behaviour identified algorithmically, we have ‘signature strikes’. Signature strikes are killable bodies ‘on the basis of behavior analysis and a logic of preemption’ (Wilcox 2013: 16). Involuntarily, we all contribute to the functioning of these big data systems and techniques that produce ‘patterns of death’ (Pugliese, 2013: 193) in the ways we connect our daily activities to the internet, for it is against ‘normal patterns of life’ that the suspicious patterns are identified and targeted, processed especially through quantitative social network analysis (Wilcox 2017: 16).

Not a Game, gouache and watercolour on paper 56 x 75.6 cm, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

The focus of Brimblecombe-Fox’s work on surveillance does not mean that it neglects the drone’s function as a killing machine. None of the paintings collected in Dronescapes depict bodies, neither targeted bodies nor bodies operating drones. Above all, there are no dead bodies. Indeed the main theme of Dronescapes is surveillance rather than targeted killing, and therefore the absence of dead bodies should not come as a surprise. However, this could be understood as an act that disembodies the experience of those who live in fear of drones. It could also charge Brimblecombe-Fox of fetishizing the drone, especially because of the detailed outline that she paints of it. The choice of not representing bodies is certainly part of the artist’s artistic licence. But I maintain that the withdrawal of the body in Dronescapes is a gesture of artistic resistance. Brimblecombe-Fox’s paintings refuse to make the body available to the drone-assemblage, thus crippling it.

Critical scholars like Lauren Wilcox (2015) and Caroline Holmqvist (2013) have rejected the idea that drone warfare is disembodies and demonstrated that the body is a central element. In particular, they have analysed the drone as an assemblage of bodies of flesh, bodies of steel, and bodies of technology. While often times drone warfare is conceptualised as disembodied, this understanding obscures that rather than being replaced by technology, human pilots are integrated with technology (Wilcox, 2015: 140; 2017: 14). Furthermore, the assemblage of the soldier/technology/machine is only complete when the targeted body of the enemy is added in, for it gives purpose to the drone-assemblage (Wilcox 2014: 151). Despite the centrality of bodies in drone warfare, they are completely absent in Brimblecombe-Fox’s work. In some respects, this is an act that visually renders drone warfare a disembodied business. However, this act of visual disembodiment is not an unsophisticated one.

If we accept that the drone is intrinsically connected to the body as Wilcox and Holmqvist suggest, then subtracting the body when visually corporealising the drone, like Brimblecombe-Fox’s art does, can be understood as a way of crippling the drone. Not only drones do not fly without human bodies to direct them, but they also have no purpose if there are no bodies to target.

First, Brimblecombe-Fox refuses to anthropomorphise the drone by ascribing human qualities to it, most notably vision. ‘Drones scope, they do not see’, she has remarked time at time again in her conversations with me. Painting the drone as it really is, paying attention to the details of its figure, eschews possible anthropomorphic interpretations. While the human-machine relation is complicated through the drone (Wilcox, 2015), Brimblecombe-Fox wants to maintain the machine-qualities of the drone, in ways that pose critical questions about the ways the anthropomorphisation of weapons increasingly justifies the automatization of killing. The naming of bombs ‘smart’ as well as the inscription of human vision onto the drone legitimise the use of these instruments of killing on the basis that they are as functional as, and more efficient than a human being at killing. What ensues from this anthropomorphisation of weapons, however, is the reduced responsibility and accountability in the act of killing. Upon this, Brimblecombe-Fox maintains that drones are machines and so they should be treated, for we cannot afford to give human qualities and devolve responsibilities to them.

Second, by avoiding to represent the bodies targeted by drones, Brimblecombe-Fox eludes the aestheticisation of death, and the voyeuristic gaze on violence. Even more important though, she never attempts to colonise the experience of those who live in countries where drones populate skies. As Brimblecombe-Fox herself does not have that experience, she has been careful not to appropriate it through her artistic work. Rather, Dronescapes invites us to think critically about our contribution to drone warfare and its effect on humanity. Brimblecombe-Fox says,

If people are fearful of the sky this represents a denial of individual and collective freedoms at many devastating levels. If the sky is diminished for some, then it is also diminished for humanity as whole.

Brimblecombe-Fox is very knowledgeable about drone warfare and well aware of targeted killing involved in some drone operations. While she does not represent dead bodies, she does not let killing pass unnoticed. Her way of rendering it, in a way that is respectful of the people who experience it, is through colour. The drones’ outlines in her Dronescapes are set against cosmic skies, often made dramatic by the use of red over blue. The viewer cannot but think of human blood spilled in countries like Yemen, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, where drones kill. The painting The Edge dares the viewer not to think of death when they look at the bloodied landscape. A disturbing deep blood red mixes with the dust of Earth. From a cosmic perspective, typical of Brimblecombe-Fox’s work, red and blue allude to stardust from which we came and to which we will return, inevitably. This reading makes the purpose of war seem even more abjectly futile. The drones, semi-hidden behind the clouds, do not look innocent, but certainly show an indifferent attitude. They have just done their job. Are you comfortable with it?

The Edge Gouache on paper 30 x 42 cm 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

Furthermore, the absence of dead bodies targeted by drones indicates that Brimblecombe-Fox is not attempting to make us witness of war, like war art often does (Danchev, 2015). Witnessing is easily co-opted into narratives of power and risks producing compassion fatigue. Brimblecombe-Fox wants the viewer to become a critical thinker and a bearer of hope, rather than a traumatised witness. Her tool to do that is the tree-of-life, an age-old symbol of humanity shared by many cultures and religions, including Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. An example of Brimblecombe-Fox’s use of the tree-of-life is the painting New Shoots. Here, like in many of the paintings belonging to Dronescapes, the tree-of-life has multiple purposes. First, it is under the drone’s scopic range to symbolise the existential risk posed by some modern technologies. Second, it represents that the risk is shared across humanity. While droned skies might be geographically specific, we all share the same existential risk, regardless of culture and religion. Finally, it is a symbol of hope and resistance.

A closer analysis of the painting New Shoots helps us to see the act of resistance symbolised by the tree-of-life. The painting presents a drone that occupies a large part of the paper. It is targeting a red and blue tree-of-life. Red indicates blood, in its loss and regenerative capacities, while blue acts as a shadow that protects the tree-of-life from the drone’s scope while it sends signals to another smaller green tree which, Brimblecombe-Fox explains, stands for fresh new life. During her time living in rural Australia, Brimblecombe-Fox has come to realise the self-regenerating potentials of life. Trees are the emblem of that. Thus, the trees-of-life in Dropescapes aims at sending a message of hope across humanity, an incitement to resist.

New Shoots Gouache on paper 30 x 42 cm 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

As a civilian woman, Brimblecombe-Fox has no experience of warzones. But the realisation of her, and our, contribution to drone warfare by means of technology has encouraged her to make a not-so-visible war visible to civilians. Brimblecombe-Fox’s body was not militarised, as she never trained and lived with soldiers like official war artists do; but she has realised that the ‘droning’ of experience indirectly militarises our lives. She wanted to expose that, and decided to use painting as her tool. Painting is a practice that does not need digital technology to be operated. It does not produce metadata in the process. In this respect, the experience of painting cannot be droned. Painting is a work of creative imagination that could prompt demilitarisation. Its power lays in the ability to visualise what might be thought to be beyond representation, like drone warfare, or rape in war (Bourke, 2017b). Hopefully Brimblecombe-Fox’s powerful visualisations will nudge viewers to exercise critical thinking and reflect on the droning of their own experience, its implication in drone warfare, and on ways to demilitarise our lives.

War art is not about passive contemplation of beautified spectacles of war. War art belongs to what Jill Bennett (2012: 2-3) calls ‘practical aesthetics,’ an aesthetics that is derived from practical and real-world encounters, and which sets to apprehend the world via sense-based and affective processes. For some, war art might seem indulgent, a way to orbit around the problem of political violence without ever doing anything to address it. In order to understand the politics of war art, one has to think of aesthetics beyond representation. Aesthetics does not equal representation. The philosopher Jacque Rancière (2004) has famously claimed that aesthetics is an intervention in the distribution of the sensible, that is, in the prevailing modes of perception in a given society. Jill Bennett (2012: 63) builds on this and suggests that the scope of art in not to replicate an event, but rather to ‘draw bodies into sensations not yet experienced.’ Thus, when art makes something invisible, like the drone, visible to audiences that are geographically and emotionally far removed, art is making an intervention into the prevailing distribution of the sensible. But sensations and perceptions cannot be reduced solely to making the invisible visible. They also encompass the realm of affective cognition, that is, the knowledge derived from the emotive responses of the body in the encounter with the other, human and non-human. Affective cognition is an important yet understated component that participates in social and politics configurations. Art’s currency is emotions, and therefore it is a crucial site of affective cognition. In Brimblecombe-Fox’s work, the politics of aesthetics is manifest not just in the exposure of the drone, but also in its staged encounter with surveillance, silent and silenced death, and shared existential risk, as well as the ensuing emotions of anxiety, horror, and hope.

References

Andrejevic, M. (2015). The Droning of Experience. The Fibreculture Journal, (25), 203–218.

Bennett, J. (2012). Practical Aesthetics: Events, Affects and Art After 9/11. London, New York: I.B. Tauris.

Bourke, J. (2017a). Introduction. In J. Bourke (Ed.), War and Art: A Visual History of Modern Conflict. London: Reaktion Books.

Bourke, J. (2017b). Rape in the Art of War. In J. Bourke (Ed.), War and Art: A Visual History of Modern Conflict. London: Reaktion Books.

Danchev, A. (2015). On Good and Evil and the Grey Zone. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Grayson, K. (2012). The ambivalence of assassination: Biopolitics, culture and political violence. Security Dialogue, 43(1), 25–41.

Gregory, D. (2012). From a View to a Kill: Drones and Late Modern War. Theory, Culture & Society, 28(7–8), 188–215.

Holmqvist, C. (2013). Undoing War: War Ontologies and the Materiality of Drone Warfare. Millennium Journal of International Studies, 41(3), 535–552.

Marlin-Bennett, R. (2013). Embodied information, knowing bodies, and power. Millennium – Journal of International Studies, 41(3), 601–622.

Pugliese, J. (2013). State Violence and the Execution of Law: Biopolitical Caesurae of Torture, Black Sites, Drones. New York: Routledge.

Rancière, J. (2004). The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible. New York, London: Continuum.

Wilcox, L. (2015). Bodies of Violence: Theorizing Embodied Subjects in International Relations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wilcox, L. (2017). Embodying algorithmic war : Gender , race , and the posthuman in drone warfare.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Poems from Guantánamo: Writing as an Everyday Practice of Resistance

- The “Drone” Lexicon

- Devouring Brazilian Modernism: The Rise of Contemporary Indigenous Art

- Extractivism and Resistance: Gendered Perspectives on the Global Resource Economy

- Droned Lives, from Gaza to the World

- Kill Empowerment: The Proliferation of Remotely Piloted Vehicles