Piracy seems to be a notion of ages ago yet it is far from gone. News reports over the last couple of years show that pirates are far from extinct and that they are still very active. This may seem a paradox with today’s modern technology and society, however, as will be described later on, the variable of technology can work both ways. This paper discusses some of the most actual items on the news today regarding piracy and international law, a complex issue. This paper will address:

1. Piracy throughout the ages,

2. Piracy today,

3. What is piracy?

4. Piracy & International Law,

5. Piracy & law enforcement.

In an ever globalizing world with a plethora of different actors one might wonder what then the exact definition of piracy is and whether the concept of piracy has remained the same. How long have we as a world been dealing with piracy?

Piracy Throughout the Ages

Piracy as a word was first recorded in the English language in 1419 (Wolfram Alpha, 2009). However, piracy or piracy jure gentium (piracy by the law of nations) as it is known was part of jus gentium (law of nations), Roman law (de Souza, 2002). Piracy as a word comes from the Greek word “peirateia” (Mirriam Webster, 2009), thus making piracy a problem of all ages.

In certain cases, piracy spiraled out of control. With the Illyrians in 233 B.C., The Roman Empire had to protect Italian and Greek traders from a common enemy after shipping routes were constantly under attack of pirates. It took three (intricate) military campaigns to defeat the threat on sea. Yet piracy didn’t disappear from the history books after that (de Souza, 2002). It continued to persist in various locations worldwide. England has historically had much jurisprudence experience related to piracy throughout its history as a sea fairing nation. Some examples are the Offences at Sea Act 1536 (UK).

The issue of piracy had such a profound impact throughout the ages that by the sixteenth century jurists such as Grotius had already developed the concept that nationals who committed piracy on terra nullius (the high seas) placed themselves beyond the protection of any state and were deemed hostes humani generis (enemies of the human race). Consequently, such offenders were able to be tried by the courts of any state for the crime of piracy (Grotius, De Jure Belli ac Pacis, Volume II, chapter 20, §40).

This was reaffirmed in re Piracy Jure Gentium [1934] AC 586 and piracy jure gentium was defined later in article 15 of the High Seas Convention in 1958. Even later, it was again reaffirmed in article 101 of the 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea. This shows that piracy still exists today.

Piracy Today

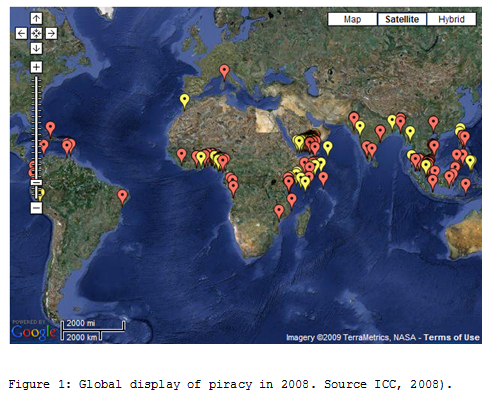

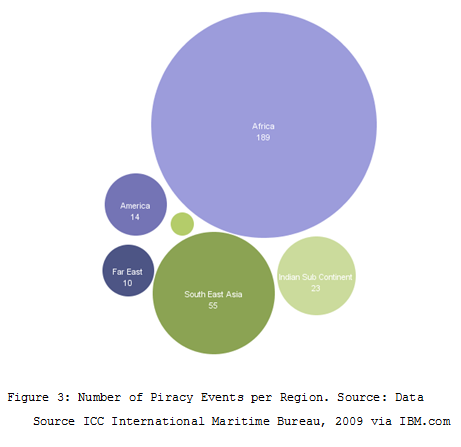

In 2008 there were a total of 261 incidents involving piracy of which 42.5% took place in the Gulf of Aden (ASIL, 2009). This includes actual attacks and attempted attacks. Piracy seems to be focused in the following areas: South East Asia and the Indian Sub Continent, Africa and Gulf of Aden, and South and Central America (see Figures 1 and 3). Piracy, however, is not confined to one specific region or regions as on December 20th of 2008, four armed robbers boarded an anchored yacht and pillaged valuables and personal property of crew and passengers at Golfe de Porto Novo, Corsica. Piracy is an international crime and was believed to have disappeared from modern times by many. The International Maritime Organization’s statistics on piracy show 1.751 incidents from 1984 to December 1999. The incidents in 2007 alone were the most significant increase of this international crime in nearly two hundred years (ASIL, 2009).

The sudden increase of piracy can be attributed to several factors. Technology has made it possible to build bigger and more complex ships and one of the factors involved in this is the need of small crews manning these large advanced vessels. By doing so, these vessels are making themselves vulnerable to small groups of pirates that can board and take control over the ship, its cargo and crew.

The lack of adequate diplomatic representation in areas where vessels fly flags of convenience and poor countries with large coastlines who aren’t able to afford and maintain adequate patrols of their territorial waters or adjacent high seas (Bantekas & Nash p. 94, 2003).

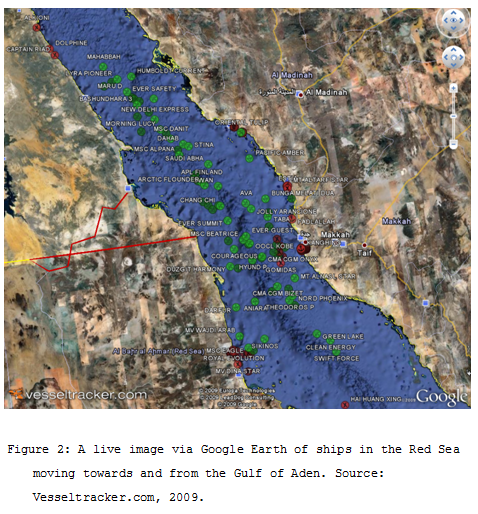

Another contributing factor is geography. In some cases, like the Suez Canal, vessels must pass through a narrow straight between the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. This, combined with forenamed factors, increases the risk of passing vessels being boarded by pirates that operate from Somali waters. The distance for pirates to reach a ship is marginal in this case but does pose a problem for those who wish to combat pirates as there are different rules for the high seas and the territorial waters of a state, in this case Somalia (Figure 2).

Due to the fact that globalization is not a homogenous process throughout, it is easier to explain why certain regions are more susceptible to developing piracy than others (Bennet & Oliver, 2002). In the case of Somalia, there is not a central government that has the resources or will to combat the pirates, yet the pirates do have the technological advancements to their disposal to pose a threat (BBC, 2009).

As with many other international problems the international community is striving to find a common solution for certain problems, be it through customary law or even special treaties to combat specific scenarios that have not yet appeared before.

What is Piracy?

Piracy is a crime under international law and municipal law. Piracy jure gentium under international law is different from piracy under municipal law. Offences that fall under the definition of municipal law do not necessarily fall within the definition of piracy under international and, subsequently, are not susceptible to universal jurisdiction (Shawn, 2008).

Because of its nature and long history, piracy has become an international crime based on customary law between the nations of the world, the law of nations. As the world further globalized after World War II, there was an apparent need for more regulation and codification besides the law of nations and certain treaties. At first the Convention of the High Seas was created in 1958. However, as time passed, this was not enough. Thus, in 1982, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was created. In this, states have certain duties and rights regarding the seas and the maritime belts also known as baselines. UNCLOS provides in this as it provides for two baselines, an important factor in determining the twelve nautical mile range for territorial waters. States retain sovereignty in both internal and territorial waters but they have an obligation to grant the right of “innocent passage”, as long as this does not impede on the state’s security (Bantekas, Nash, 2003 ).

Piracy jure gentium is defined in Article 101 of the Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 as following:

(a) any illegal acts of violence or detention, or any act

of depredation, committed for private ends by the crew or

the passengers of a private ship or a private aircraft,

and directed:

(i) on the high seas, against another ship or aircraft,

or against persons or property on board such ship or

aircraft;

(ii) against a ship, aircraft, persons or property in a

place outside the jurisdiction of any State;

(b) any act of voluntary participation in the operation

of a ship or of an aircraft with knowledge of facts

making it a pirate ship or aircraft;

(c) any act of inciting or of intentionally facilitating

an act described in subparagraph (a) or (b).

The definition above is in line with customary law; however, the actus reus of this offence is not dependent on factors such as gravity or an intention to act openly (Bantekas, Nash, 2003).

Key factor in the definition of piracy is that it must be performed by a private ship/aircraft for private ends by the crew or passengers, successful or not. This means that attempts also are categorized as piracy. If a person commits otherwise unlawful acts against property or persons of a country on the high seas, that person is not automatically an enemy of mankind, but merely of that one specific country. As soon as there is another motive, e.g. a political one then it no longer constitutes as piracy jure gentium. This by itself does not automatically mean that the existence of a political motive justifies any acts of insurgency (Bantekas, Nash, 2003).

A pirate and privateer are not the same, although the thin distinction between the two is the letter of marque or “letters of marque and reprisal.” The U.S. Supreme Court stressed that a piratical act, is an act of aggression unauthorized by the law of nations and without the sanction from public or sovereign authority (United States v. The Brig Malek Adhel, 43 U.S. 2 How. 210 210 (1844)).

Piracy & International Law

Despite globalization and interdependence, international law still has not yet developed in such a manner that it can address certain problems through universal enforcement (Bennet & Oliver, 2002). On the contrary, globalization has become a factor that works both positive and negative in the combat against piracy. As states started to organize themselves on a more effective way with the use of technology, so did pirates find different manners to setup transnational criminal networks (Bedermann, 2007). Piracy is one of those problems that require a universal approach. As pirates make no discrimination among vessels, it is therefore a common problem, or a problem of all nations. Since the times of Grotius and others, pirates were considered hostis humanis generis. The best basis to address problems of a universal nature is through cooperation or the universality principle. Piracy has, as already stated above, been a problem of all ages, and slowly also of all nations with the expansion of shipping routes. By the sixteenth century, the concept of piracy and exclusive jurisdictions were already developed, yet this by no means meant that the piracy problem was resolved for good.

Because of the nature of piracy, any state may seize a pirate ship or aircraft, be it on the high seas or on terra nullius. The persons may be arrested and the property seized. The courts of the state that is carrying out the seizure has jurisdiction to impose penalties, and may decide what action to take regarding the ship or aircraft and property, subject to the rights of third parties that have acted in good faith (Shawn, 2008).

Piracy as a crime in international law is an exception as there is much emphasis placed upon the sovereignty and jurisdiction of each particular state within its own territory. This could also be a contributing factor to the success of defining piracy as a crime the way it is. All parties gain from this without giving away any rights. However, transnational organized crime is hard to suppress partially due to the state sovereignty. This can often frustrate the combat of transnational crime due to formalistic rules of jurisdiction.

Another factor that plays a pivotal rule is the rule of law. Although most of nations of the world provide a penal code for piracy in their own law, enforcing this law is not as easy as it may seem. Despite the universality principle, the law of nations, customary law and UNCLOS there are still many areas that are not properly addressed.

Piracy & Law Enforcement

The sudden influx of piracy cases during the last couple of years has sparked public interest. The Maritime Safety Committee has given recommendations and the International Chamber of Commerce has even started a live piracy reporting service in which is shown which ship, where has been hit by pirates.

The international community has reacted swift to the piracy problem by creating an unprecedented international naval cooperation. In this initiative the navies of the United States, Great Britain, France and India play the lead role (ASIL, 2009). This coalition, for the first time in history, includes the first ever European Union naval force and represents the first time that China has deployed its naval force outside of South Chinese Sea region (ASIL, 2009). Through this effort, the coalition managed to fence off pirate attacks. They did not, however, pursue and apprehend them. Added to this, are the costs of this operation, making it an expensive undertaking. The international community has realized that a proper approach involves not only defending vessels but that it also involves apprehending the criminals.

The United Nations Security Council has passed five resolutions in 2008 dealing with piracy in Somalia. These were passed pursuant to Chapter VII of the UN Charter, allowing the use of military force against threats to international security (ASIL, 2009). On the 16th of December 2008, the United Nations Security Council passed an even broader resolution, extending the authorization of military force to land-based operations in Somalia (Security Council 6046th Meeting (PM), 2008).

On the 16th of January 2009, the United States and Kenya signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU). Kenya signed a similar memorandum with the European Union. On their turn the U.S. and E.U. provide Kenya with the necessary help and assistance. In this memorandum Kenya agreed to try suspected pirates captured by the U.S. One of the reasons for this is that other countries are reluctant to put pirates on trial as they are foreign nationals with no mailing addresses, or finding a Somali translator. These practical problems, which can be costly, have now been resolved by the Kenyan solution.

Subsequently the international community is stepping up its efforts in combating piracy by assisting Somalia through donations that will help to improve the security on its coastal lines and sea (NYT, 2008).

Summary

Piracy jure gentium is a crime under international law and the law of nations that is far from gone. Although international law provides for means to define and conceptualize this particular crime in Article 101 of the Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982. There is still a lot of ground to cover. Despite this, the international community has, with an overwhelming majority, managed to anticipate on these new developments of piracy. This even led to the unanimous adoption of U.N. Resolution 1851 (2008).

Yet despite customary law, international law and municipal law the underlying problems have again appeared. Not only is it required that the international community acts against crimes like piracy, but a more pro-active approach is deemed necessary as the cooperation between Kenya and its Western partners show. Regionalism despite globalization offers a myriad of possibilities to combat and prevent piracy, but have not yet been fully exhausted (ASIL, 2009). Because globalization is not a homogenous process certain countries, are not in the position to properly anticipate and combat crimes like piracy alone. The acceptance of aid by other states reiterates yet again that piracy is indeed part of jus gentium and that despite the complexity of the problem it also offers the international community new ways to cooperate closer on a common problem (Bennet, Oliver, 2002).

References

United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, Articles 26 to 48 and 61 to 65 of the Draft of the International Law Commission (A/3159), http://untreaty.un.org/cod/diplomaticconferences/lawofthesea-1958/docs/english/vol_IV/13_ANNEXES_2nd_Cttee_vol_IV_e.pdf

Malcolm N. Shaw, International Law 1265 (6th ed. 2008).

A. Leroy Bennett & James K. Oliver, International Organizations; Principles and Issues (7th ed. 2002).

Matthew Harvey, Piracy: High Seas, Violent Theft, and Private Ends, http://esvc000873.wic005u.server-web.com/docs/Harvey_paper.pdf, (Last visited, 09-20-2009).

Ilias Bantekas & Susan Nash, International criminal law ((2nd ed. 2003)

Joseph Chitty, The Law of Nations, http://www.constitution.org/vattel/vattel.htm , (Last visited, 09-20-2009).

BBC, France charges Somali ‘pirates’, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/7355598.stm, (Last visited, 09-20-2009).

Miriam Webster, Definition Piracy, http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/piracy , Last visited, 09-20-2009).

Wolfram Alpha, Piracy, http://www.wolframalpha.com/input/?i=piracy , Last visited, 09-20-2009).

United Nations Security Council, Security Council authorizes states to use land-based operations in Somalia, http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2008/sc9541.doc.htm , (Last visited, 09-20-2009).

International Commercial Crime Services, International Maritime Bureau, http://www.icc-ccs.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=27&Itemid=16 , (Last visited, 09-20-2009).

ASIL, International Legal Responses to Piracy off the Coast of Somalia, http://www.asil.org/insights090206.cfm , (Last visited, 09-20-2009).

David J. Bederman, Emory International Law Review, http://www.lexisnexis.com.ezproxy1.apus.edu/us/lnacademic/results/docview/docview.do?docLinkInd=true&risb=21_T7380771506&format=GNBFI&sort=RELEVANCE&startDocNo=1&resultsUrlKey=29_T7380771509&cisb=22_T7380771508&treeMax=true&treeWidth=0&csi=143873&docNo=21 , (Last visited, 09-20-2009).

United Nations, Oceans and Law of the Sea, http://www.un.org/Depts/los/index.htm , (Last visited, 09-20-2009).

Hugo Grotius, On the Law of War and Peace, http://www.constitution.org/gro/djbp.htm , (Last visited, 09-20-2009).

Philip de Souza, Piracy in the Graeco-Roman World, (2002).

Privy Council, In re piracy jure gentium, http://www.uniset.ca/other/cs5/1934AC586.html , (Last visited, 09-20-2009).

—

Written by: Sergei Oudman

Written at: American Military University

Written for: Professor Constance A St Germain Driscoll

Date: 2009

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Piracy in the Southern Gulf of Mexico: Upcoming Piracy Cluster or Outlier?

- Is There a Right to Secession in International Law?

- International Law on Cyber Security in the Age of Digital Sovereignty

- Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Imperialist Dynamics in International Law

- A Rules-Based System? Compliance and Obligation in International Law

- To Reform the World or to Close the System? International Law and World-making