As the neighbouring state most comparable to Turkey in geographic, demographic and socio-economic size, relations with Iran differ from all other neighbourly relations, as Iran is considered Turkey’s equal. As such, the relationship is also filled with historical legacies that have shaped public and elite perceptions. First, there is the legacy stemming from the century-old rivalry of the two former empires (Ottoman and Persian) whose competition was territorial, political, cultural as well as religious. Furthermore, the parallel decline of imperial strength – both in Constantinople and in Tehran – gave rise to a shared struggle against the encroachment of outside powers, mainly Russia and the West. The second legacy derives from the experience as modern nation-states and is rather amicable. It originates in Turkish and Iranian affinity to modernise in the face of superior enemies, guiding the two countries in their transition to modernity. Notably, Reza Shah’s only visit abroad took him to Turkey in 1934 to inspect his western neighbour’s reforms and social engineering. After World War II, the two states were nominal allies of the Western bloc though the institutional arrangement – the Central Treaty Organisation (CENTO) – was effectively dormant. Instead, Iran’s natural resource wealth soon enabled the country to eclipse Turkey’s developmental level and Iran’s reassertion of influence resurrected Turkish memories of a threat from the East.

Relations with Revolutionary Iran

This had been the context of the Iranian Revolution in 1979. Relations with the Islamic Republic have henceforth vacillated between restrained tension and tacit cooperation, usually depending on Iran’s foreign policy priorities. Iran’s revolution had initially been welcomed by Turkish leaders due to internal political and economic weakness. Yet despite Turkey’s immediate recognition of the Khomeini regime, the ideological contrast between the two regimes was stark and grew stronger with the 1980 military coup in Turkey. The impending clash was only averted through the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War, creating incentives for Turkey and Iran to deepen cooperation. Ankara was reeling from an economic crisis and the 1980 coup had also left it politically weakened on the international stage. At the same time, Turkey proved to be the only viable trade and transport route for Iranians. Government-negotiated barter deals – oil for consumer and industrial goods – ensured stable Turkish-Iranian relations free of political differences for most of the war. However, Iran’s offensives indirectly created a safe haven for the separatist Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) to launch an insurgency inside Turkey based on Iraqi soil. Toward the end of the war, Turkey’s military response to the PKK increasingly made it a party to the conflict in support of the objectives of the Baghdad regime. This development and the simultaneous collapse in world oil prices diminished the importance of economic ties and Turkish-Iranian relations became more fractious.

Iran after 1989, post-Iran-Iraq War and post-Khomeini, was focused on overcoming its international isolation, advancing reconstruction and retaking a recognised role as part of the regional order. In this context, Turkey was neither expected to provide assistance nor pose a major obstacle to Iranian regional designs. However, the momentous changes in the global order with the end of the Cold War complicated Turkish-Iranian tensions as power shifted decisively toward the US-affiliated camp. In addition, Turkey’s initial exuberance over reconnecting with its Turkic brethren in the Caucasus and Central Asia briefly elevated Turkey to an Iranian national security threat in the early 1990s. In response, Iran undertook great effort to stem Turkish influence by backing the PKK as well as Islamic fundamentalists inside Turkey to destabilise its political system. Tensions reached a crescendo in early 1997, due to the rise of political Islam inside Turkey and Tehran’s embrace of Turkish Islamists, in part contributing to the ‘post-modern coup’ in February 1997. This also ushered in a more militarised Turkish foreign policy that softened after the apparent victory over the PKK in 1998-1999. Thereafter, lacking any security dimension, Turkish-Iranian relations became uneventful and centred around energy trade. Turkey’s economic crisis in 2000-2001 further subdued relations with Iran, preoccupying Turks with internal problems and international financial pressures. The political reaction to the economic meltdown was the November 2002 election that replaced most of the Turkish leadership and set the country on a new path internally as well as in its foreign relations.

Normalisation of Relations since 2002

While Turkish-Iranian rapprochement began in 2000, three fundamental parameters of the bilateral relationship have been transformed since 2002. First, Turkey’s domestic politics underwent profound change. The 2002 election of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) heralded a new leadership in Ankara. Moreover, this new elite set about altering the character of the Turkish state in a manner that diminished the military-bureaucratic influence and with it, the ideological differences between Turkey and Iran. In detail, due to a 10% electoral threshold, only two parties managed to enter parliament: the moderate Islamist AKP with 34.5% of the vote and the staunchly Kemalist Republican People’s Party (CHP) with 19.5% of the vote. In light of the quirks of the electoral system, 45% of the electorate remained unrepresented in parliament, and the AKP received 363 seats, four short of a two-thirds majority. This new constellation was akin to regime change. Turkish columnist Mehmet Ali Birand called it “a civil coup”, and the Turkish daily Milliyet summed up the seismic shakeup of the elite with the football metaphor “Red Card” posted above the faces of the political leaders ousted from parliament. Viewed from Iran, the previous elite had stood for a security-oriented, ossified Kemalist worldview, which was deeply hostile to Turkish engagement with the Islamic world, particularly Iran. In this regard, Tehran struggled to hide its pleasure of the Turkish public’s wholesale rejection of the old elite.

Furthermore, the AKP gradually infused Turkish foreign policy with a novel worldview of Turkey being a central player in its own right, thus emphasising greater regional activism and trade-driven foreign relations. In this context, the AKP drew on the a new foreign policy paradigm in the writings of Professor Ahmet Davutoğlu that laid out the vision of Turkey as a global power at the crossroads between East-West and North-South. His worldview was a whole-hearted repudiation of the Kemalist ‘bunker mentality’, which the AKP also considered linked to the perpetuation of elite rule inside the country. Indeed, ‘strategic depth’ posits a different worldview of how to think about Turkey’s role in the world, leveraging the country’s geo-strategic location and historical depth. In order to build on these inherent assets, Turkey needed to resolve longstanding tensions with its regional neighbours, particularly Iran, a policy later termed ‘zero problems’. Moreover, claiming to form a centre and not simply a peripheral member of any axis, Ankara needed to re-balance its relationships. Instead of solely being a junior anchor of the Western alliance, Turkey needed to create multiple alliances that maximised its operational independence and helped to maintain a balance of power in its adjacent regions. Davutoğlu foresaw this approach to be accompanied by substituting the ‘security-oriented’ Kemalist outlook with a new ‘economy-oriented’ foreign policy. Together with the AKP discourse of political Islam, this new approach has facilitated identifying common ground with Iran and strengthened the two countries’ rapprochement in the past decade.

Second, the strategic environment and Turkey’s foreign relations entered a new era due to the US invasion of Iraq. Ankara’s rejection of support for the invasion and the gradual deterioration of the Turkish-US relationship lessened Turkey’s image as a US ally in the eyes of Iranians. Before Erdoğan had formally taken office, the impending US invasion of Iraq posed a major foreign policy challenge to the AKP government. Despite the generous offer of US assistance, elite opinion began to follow the general public with rising nationalist sentiment, growing skepticism over US motives and memories of the cost incurred during the Gulf War in 1991. The discussions culminated in the historic parliamentary vote on 1 March 2003, which denied Turkey as a staging ground for US troops. Though many observers termed the vote an ‘accident’ or a ‘managerial failure’ by Erdoğan, others identified it as the beginning of a policy of distancing Ankara from US influence in the region. Whereas this was widely viewed as a political catastrophe for the AKP at the time, it proved to be a blessing for Turkish-Iranian relations. The parliamentary vote was a key turning point in the bilateral relationship, as Ankara sensed a profound change of attitude from Tehran thereafter. It confirmed Tehran’s initial impression that the election of the AKP indeed heralded a new era of independence in Turkish foreign policy, one that dared to counter US preferences. Moreover, Iran considered the increased democratisation of Turkey to be to its benefit, as it has assumed the majority of the Turkish public to be sympathetic to their eastern neighbour for religious and cultural reasons.

Moreover, the Iraq War generated a convergence of Turkish-Iranian strategic interests for three reasons. First, Iran was confronted with large-scale US troop deployments on two of its borders, feeling increasingly besieged and thus eager to mitigate the US threat. Second, US-Turkish relations drastically worsened after the 1 March 2003 vote and once US troops had occupied Iraq. This was both due to political and operational failures as well as to the simple fact that the two allies had grossly different objectives in post-Saddam Iraq. The growing gap with Washington allowed or even induced Ankara to pursue other strategies. And third, both Iran and Turkey faced the prospect of an independent Kurdish state that would pose an irredentist threat to their national borders. Moreover, the fall of Saddam’s regime and explicit Kurdish support for the US occupation facilitated the re-establishment of a safe haven for the PKK and the re-start of an insurgency. This was not only a challenge to the Turkish state, as the PKK spawned or cooperated with the Free Life Party of Kurdistan (PJAK), a similar group battling the Iranian state. Under these circumstances, increased Turkish-Iranian cooperation in Iraq was foreseeable, though it would eventually become tempered by competitive impulses over how to fill the power vacuum in Iraq and the Middle East.

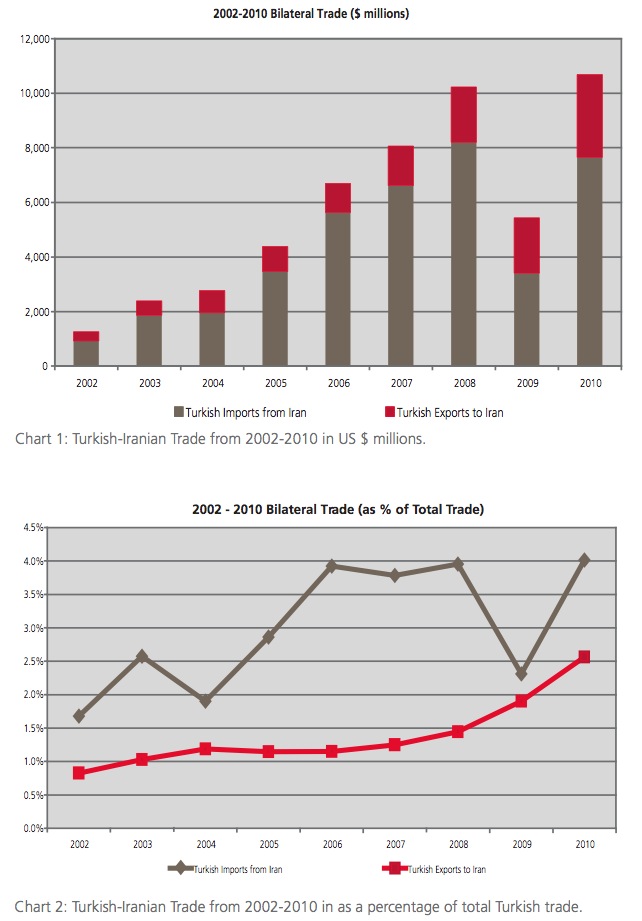

On the economic front, Turkey’s rapid economic boom was predicated on a trade-driven foreign policy, with Turkey boosting exports of manufactured goods and specialised services in return for an expanding Iranian energy supply. In this context, the AKP government has considered it a strategic necessity to expand commerce and trade with Iran, regardless of Western concerns. As Davutoğlu explained in 2007, “here all our allies should take into consideration Turkey’s unique position. As a growing economy and surrounded by energy resources, Turkey needs Iranian energy as a natural extension of its national interests. Therefore, Turkey’s energy agreements with Iran cannot be dependent upon its relationships with other countries.”[1] Chart 1 illustrates the boom in Turkish-Iranian trade, which languished at barely over $600 million in 1998. By 2004, trade stood at close to $3 billion and exceeded $10 billion in 2008. This 15-fold increase over a decade is impressive, though not by the standards of overall Turkish trade growth, particularly with other regional partners. A look at Chart 2 shows that as a percentage of Turkish exports, Iran roughly doubled its share from 0.73% in 1998 to 2.01% in 2009 and ranking as the 14th largest export market. As a percentage of Turkish imports, imports from Iran actually experienced a more rapid increase, rising from 0.94% to 4.06% in 2008 before dropping to 2.42% in 2009. Above all, the composition of bilateral trade is essential to understanding the fluctuations in recent years. More than 80% of Iranian exports are energy exports, either natural gas or oil, and therefore the nominal amounts are a function of Turkish energy consumption and the world market price of energy. In contrast, Turkish exports are less volatile as they are concentrated in industrial goods, infrastructural services and tourism.

Data from the Turkish Undersecretariat of the Prime Ministry for Foreign Trade, found at www.dtm.gov.tr

In similar fashion to the deterioration in US-Turkish relations, Ankara’s ties to the EU worsened after the historic October 2005 recognition of Turkey as an official EU accession country. Initial euphoria was soon followed by a de facto freeze over the Cyprus issue, turning Turkish public opinion against the EU and slowing Turkey’s drive toward integration with the West. Turkey’s primary security concern was how Iraq’s instability was reinvigorating the PKK-led insurgency. In this context, by mid-July 2006, the region was preoccupied with the outbreak of the Israel-Hizbullah War, widely seen as a pivotal moment in the proxy war between Iran and the United States. Simultaneously, Iran had provided its territory for the Turkish military to prepare an assault near Qandil valley. Throughout August, Turkey and Iran were jointly bombing alleged PKK / PJAK camps inside Iraq, with daily reporting following the coordinated Iranian and Turkish operations. The details of the exact nature of the operations, such as casualty figures, are difficult to verify. Yet the impact on Turkish public opinion was clear: Iran was supporting Turkey in its counter-terrorism struggle while the US and Europe were either apathetic or in collusion with Turkey’s enemies. Since 2006-2007, most Turkish opinion polls consider the United States the greatest threat to Turkey, only a minority of Turks endorse EU membership and Iran enjoys favorable public opinion. The AKP was thus pursuing a foreign policy in accordance with public sentiment, as Turkish sympathies for Iran had begun to override a history of sectarian and socio-political differences.

The third parameter of change was the looming confrontation between the West and Iran over the latter’s nuclear program. Foremost, it added another channel of engagement between Ankara and Tehran. Since 2006, through public statements of support, Ankara has sought to ingratiate itself with the Iranian leadership in an effort to play a mediating role in the negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program. However, behind closed doors, Turkish decision-makers have contemplated how to cope with the major security threats posed by Iran’s nuclear development. In the short term, the nuclear dispute could lead to another regional war with Turkey bearing huge economic and political costs. And in the long term, Iran’s nuclear status would decisively shift the balance of power towards Tehran, even if Turkey were not a direct target of Iranian hostility. As a result, Ankara has pursued a mixed policy aimed at preventing military conflict as well as minimising Iranian hostility, a balancing act that has caused friction with its traditional Western allies. Nevertheless, for Turkish-Iranian relations, the nuclear issue has been a boon to Turkey. It has allowed Ankara to elicit Iranian goodwill on bilateral issues, notably on opposition to Kurdish militancy and the completion of favourable energy deals that should enable Turkey to become a key energy transit corridor. Lastly, by ultimately accepting Turkish mediation on the nuclear file and by virtue of the Turkish vote against the US in the UN Security Council, Iran has reluctantly promoted Turkey’s image as the leading regional power.

Conclusion

In sum, the past decade has deeply affected Turkish perceptions of Iran. Despite Iran swinging toward greater authoritarianism, worsening domestic human rights and bellicose rhetoric, Turks no longer view Iran as a direct security threat, but rather as a regional partner whose victimisation by the Western-led international community could be detrimental to Turkish interests. In turn, Tehran has become more conciliatory, though it has not shed its ambivalence about the new role of its Western neighbour. Turkey’s newfound independence and amity toward Iran have been appreciated. In addition, bilateral Turkish-Iranian relations lack any potential irritants. If at all, Iran’s reliability as an energy supplier and the pricing of its hydrocarbon resources are the most challenging issue for bilateral ties. While the Iranian market continues to offer great opportunities for Turkey’s exporters, the relationship lacks the potential glue for any deeper political partnership.

On the other hand, the regional factors that have advanced rapprochement between Tehran and Ankara have largely run their course. Iranian scepticism concerning its Western neighbour is rebounding, particularly as Turkey’s status as a regional power will increasingly be in direct competition to Iranian foreign policy objectives. This competition will primarily play out in the construction of the new regional order in the Middle East. It was already visible in 2010 over the election and formation of a government in Iraq. Moreover, the two countries have very different hopes and fears regarding the Arab uprisings, which have only just begun to unfold.

Elliot Hentov recently received his Ph.D. in contemporary Turkish and Iranian affairs at Princeton University’s Department of Near Eastern Studies. Mr. Hentov’s publications have appeared in the New York Times, Financial Times, the Washington Times, Foreign Policy, The Washington Quarterly and he has also been a featured speaker on Middle Eastern affairs. Mr. Hentov is also a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations and a Fellow with the Truman National Security Project.

Elliot Hentov recently received his Ph.D. in contemporary Turkish and Iranian affairs at Princeton University’s Department of Near Eastern Studies. Mr. Hentov’s publications have appeared in the New York Times, Financial Times, the Washington Times, Foreign Policy, The Washington Quarterly and he has also been a featured speaker on Middle Eastern affairs. Mr. Hentov is also a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations and a Fellow with the Truman National Security Project.

This article originally appeared in ‘Turkey’s Global Strategy’, an LSE IDEAS Special Report.

[1] Davutoğlu, Ahmet. “Turkey’s Foreign Policy Vision”, Insight Turkey, Vol. 10, No. 1, p. 91

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Spain’s Request For NATO Coronavirus Aid: Will Turkey Answer?

- Turkey’s Role in Syria: A Prototype of its Regional Policy in the Middle East

- Opinion – Turkish Foreign Policy after the 2023 Elections

- Turkey: Unopposed in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea

- At the EU-Turkey Border, Human Rights Violations are No Longer Clandestine Operations

- Russia and Turkey: An Ambiguous Energy Partnership