The introduction of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) on 1 January 1994 culminated the rapid liberalization of Mexico’s economy and completed the transition of a country renowned for its closed-border policies to a poster child for free-trade development (Wise, 2003). Certainly, many benefits have emerged out of the deal. In a country historically comprised of either rich or poor, a middle class has emerged, the manufacturing has increased over 190 per cent and overall exports to Canada and the United States between 1993 and 2001 increased over 200 per cent, accounting for over half the GDP and job creation growth in the same period (Scott, 2004; Harvey, 2001).

Unfortunately, the majority of those who tout these successes fail to acknowledge the serious degradation caused to other sectors of the economy and society—namely the bottoming out of agricultural prices; the increased hardship faced by Mexico’s poor, forcing many to migrate to larger communities and across borders; and the inherent clash of the subsequent development strategies with the cultures and ideologies of Mexico’s Indigenous peoples. Indeed, as Miller and Shannon (2002) argue in their article, “Corn, Free Trade and Cross Border Organizing,” economic development since NAFTA has become synonymous with neoliberal, export-oriented policies which facilitate foreign-direct investment. This “jolting transition associated with the insertion of local economies into regional and global economic systems have had a variety of social, environmental, and cultural repercussions for [Indigenous] communities throughout the region” (p. 1).

It is the effects of this transition on Indigenous peoples of Mexico which will be the focus of this paper. Specifically this paper will argue that via lower returns on agricultural products, increased migration, and the continued disregard for human rights in Mexico, the NAFTA has increased the negative impacts on the livelihood, culture and society of Mexico’s already most vulnerable population, its Indigenous peoples, culminating in greater poverty and dependency.

The paper will proceed in four parts. First it, will briefly explore the general situation of Mexico’s Indigenous peoples. This will be followed by a discussion of the effects of NAFTA on the agricultural sector, paying close attention to the case of corn as it relates to the plight of Indigenous peoples. Third, it will explore the connections between the degradation of the agricultural sector, migration and Indigenous communities. Finally, it will conclude with a brief examination of the major resistance movement that opposes NAFTA in the name of Mexico’s Indigenous peoples, the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) of Chiapas, and look at the human rights abuses that have occurred in connection with this uprising.

In this argument it is important to bear in mind three points. First, I write with the assumption that Indigenous peoples have a right to maintain their culture which includes the choice of subsistence living and limited involvement in the greater economy. This is supported by the Organization of American States Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, (IAHRC) which states that:

it is the obligation of the State of Mexico, based on its constitutional principles and on internationally recognized principles, to respect indigenous cultures and their organizations and to ensure their maximum development in accordance with their traditions, interests and priorities. (IACHR, 1998, art 577).

Secondly, it is important to understand that NAFTA was not the introduction of neoliberal policies in Mexico, but rather the culmination to that point (such policies have since pushed further with plans such as Plan Puebla-Panama, which seeks to employ the same export-oriented style of development for southern Mexico through to Panama). As such, in the final discussion of human rights and resistance movements in regards to NAFTA, one should bare in mind that while NAFTA is viewed as the symbol for neoliberal domination, problems in relation to liberalization began as early as 1986 with Mexico’s induction into the General Agreement on Trades and Tariffs (now the World Trade Organization) (Carlsen, 2003). Thus NAFTA cannot be wholly to blame for the human rights abuses that continue to take place within Indigenous communities, but its role must be held to account.

As a final caution, one needs to understand that Indigenous peoples have been severely marginalized since colonization. Their struggles date back hundreds of years. There is no delusion that NAFTA is the sole instigator of their plight. However, as TA Wise (2003) argues, writing for the Americas Program with the International Relations Center, the concern is that NAFTA was propagated as road out of poverty for the Mexican people and this it has most certainly failed to do. He further argues that “the Mexican experience reminds us that increased trade and investment should not be the end objectives of economic integration. Instead, they should be considered as possible means to improve social welfare and environmental quality” (p. 2). With these considerations in mind, we move on to our examination of NAFTA’s role in the Mexican Indigenous crisis, necessarily beginning with a look at the Indigenous situation of the country.

Understanding the Indigenous Situation

“The Indigenous proposal is distinct from the neoliberal proposal. It doesn’t depend on the economy. It depends on the strength of the people, of their conscience and their heart. It’s a different way of thinking. We see that if we want to take the gifts from the earth we have to work as a collective.”

– Father José de Jesus Landín

San Andrés Parish, Chiapas, 2006

Since the arrival of the Spaniards in 1519, the Indigenous groups of Mexico have been marginalized, segregated and robbed of their land—the very foundation of their spiritual and physical life. Despite efforts by former president Benito Juarez to undertake land reform in the late 1800s, the trend of large estates in the hands of few has continued to subject the Indigenous peoples to a “slave-like dependency” on the ruling power (Améndola, Epigmenio, & Martínez, 2005). As John Ross (2001) of the Latin American Press argues, policies such as those pertaining to land have effectively institutionalized racial discrimination for the past five hundred years. Indigenous peoples and the Meztiso government continue to clash over basic values and understanding of collective versus individual rights and the human relationship to land and resources.

The present standard-of-living social indicators could not demonstrate this racial discrimination more clearly. According to the World Bank (2006), of the 10.3 million officially recognized Indigenous peoples in Mexico, 89.7 per cent live in poverty while 68.5 per cent live in extreme poverty.[†]This is compared to the non-Indigenous population averages which are 46.7 per cent and 14.9 per cent respectively (The World Bank Group, 2006).[‡]Of Indigenous municipalities—defined as municipalities with Indigenous speakers being at least 70 per cent of the population—which make up roughly one-third of all municipalities, 82 per cent are described as “extremely disadvantaged” by the IAHRC (1998, art 510). These differences found in the extreme poverty rates and the communities’ standards of living are particularly telling of the ethnic divide. However illiteracy, school drop-out rates, lack of access to potable water and sanitation, infant mortality and life expectancy are also all two to four times worse in Indigenous communities when compared to the non-Indigenous population (The World Bank Group, 2006).

With statistics like these showing little sign of improvement throughout the early 1990s (Ibid), the signing of the 1994 NAFTA, which only threatened to worsen the situation despite promises of the contrary, was the last straw for many Indigenous. NAFTA is particularly threatening because its policy structure prevents even the neoliberal-inclined Indigenous groups from transitioning to export economies. As Scott (2004) explains, “poorer regions and households in Mexico have entered NAFTA severely underequipped to reap the benefits of free trade” (p 307).

Harvey (2001) attributes this to the redefinition of citizenship that has culminated with the introduction of NAFTA. Citizenship, once defined as “corporatist citizenship” where individuals were incorporated into “corporatist organizations” (p. 1046) that functioned as pillars of the statewas redefined in the mould of the Market economy where “individuals were encouraged, trained or coerced into new relationships with global networks of similarly marketised societies” (p. 1047). While Harvey acknowledged that the new definition did benefit some Mexicans, notably urban-based upper and middle classes, the majority of the rural poor, and especially the Indigenous peoples, experienced increasing poverty and exclusion from the market: “Lacking even the basic services of health care, education and housing, the majority of Indigenous communities were clearly impeded from participating in the global economy, either as producers or consumers” (p. 1048).

Indeed, the typical mentality of many Mexican Indigenous communities is collective, which is in stark contrast to the individualistic NAFTA approach. As Harvey notes, it is a clash between “market citizenship” and “pluri-ethnic citizenship” (ibid). In Oaxaca, for example, where approximately 60 per cent of the population is Indigenous, the IAHRC stated that in 1998 75 per cent of the land was owned communally, often shared amongst several different groups. (This communal land is quickly disappearing as the ejidos [communal land titles] are sold to individual owners—a part of the neoliberal constitutional reform package that was introduced in 1992 in preparation for NAFTA.) Landín (personal communication, May 14, 2006) explained that the communal format has always existed in the Indigenous communities but that cooperatives have ballooned since the mid-1980s as a way to protect the communities from the neoliberal reforms while helping to lift them out of poverty in a culturally sensitive manner.

Cooperatives ensure shared profits but also typically operate with rotating administrations providing the opportunity to all cooperative members to gain leadership and management training and thus working to improve the common dearth of human capital within the communities (personal communication, Celerina Ruiz Nuñez, President Jolom Mayaetik, May 15, 2006). Conversely, government development programs—instituted since 1994 to compliment NAFTA—provide infrastructure and housing, but fail to build any local capacity required by the people to break free of the need for future aid projects. Indeed the government is notorious for entrenching dependency as well as only rewarding neoliberal ideals by only aiding those who attempt to operate within the ideal of NAFTA; for example, converting their fields to cash crops (F.N., 2006). As Figure 1 illustrates, the result is extreme disparity within single communities.

Figure 1: Neoliberalism versus Subsistence

The house on the left was built by the government program Jornaleros Agricolas, which assists families who are landless and partake in the day labour on cash-crop farms. The house on the right is directly next door and is occupied by a family that wishes to remain close to its cultures and traditions of subsistence living.

Source: F.N., 2006

The difference that underlines this resistance to the neoliberal economic policies is the traditional relationship between many Indigenous peoples worldwide and the earth. While the non-Indigenous, Mestizo population typically sees the earth as a source of resources to be bought and sold, as Landín explaines, the Indigenous viewpoint is quite different:

The earth is not a resource. It’s a gift that we are responsible to care for. How can we buy it? It’s impossible. But the Mestizos have another idea. So it is an obstacle in our understanding because our mentalities are very distinct. … They look at us and say, ‘well you use a machete’ but it’s very distinct. We ask permission to take each tree. As Indigenous people we are part of nature. We are not apart from it. When we take a tree, it is to build our house; it’s not to negotiate with. It’s very different. We feel that we are part of the ecosystem so we don’t want to destroy it. If I destroy it, I destroy myself. If it ends, I end. (personal communication, May 14, 2006)

Dr Luz Murillo a Colombian anthropologist who has worked closely with Indigenous peoples in Mexico and Colombia offers a Colombian example to further explain the situation. She recalled the devastating results which occurred after multi-national oil companies took over land for oil extraction:

The Indians killed themselves because for them oil is the blood of the land but [oil companies] couldn’t understand that. They only saw the money there. That’s it. They didn’t see life, they didn’t see human beings, they didn’t see the environment, they didn’t see anything but money … For [the Indigenous] the land is not to sell because this is their life, the land is their mother, the air is their mother. (personal communication, April 28, 2006).

This criticism, that all the government and companies see is money, certainly is not foreign to Mexico. Since NAFTA this has only worsened, and the case of corn, which will be explored in the following section is a perfect example. However, to understand that we must first explore the effects of NAFTA on the agricultural sector in general. In doing so we will see that NAFTA has further institutionalized marginalization in Mexico, which is entrenched in the fundamental clash between liberalization and cultural protection.

The Clash of Money and Identity in Mexican Agriculture

“The Mexican state continues to view [trade liberalization] as a panacea for poverty and underdevelopment. The evidence, however, suggests that free trade agreements in general, and NAFTA in particular, have exacerbated the problems facing the rural poor in Mexico”.

– Henriques & Patel, 2004

NAFTA, Corn & Mexico’s Agricultural Trade Liberalization

When NAFTA was implemented in 1994, the promises of better jobs and better wages were heard loud and clear (Wise, 2003). Unfortunately, these promises excluded the agricultural sector, the poorest sector of the economy and also the sector most densely populated by Indigenous peoples. Instead, the exact opposite occurred. The sector, which retains more than 20 per cent of the 39 million economically active Mexicans and is already suffering from 30 per cent lower wages than other manual labour sectors like construction, saw a ten per cent decrease in—or 1.7 million lost—jobs in the first decade of NAFTA (Nadal, 2000; Wise, 2003; Henriques & Patel, 2004). This was largely the result of American imports flooding the market with much lower-priced produce. Indeed, in the same period imports of soybeans, wheat, poultry and beef increased as much as five hundred per cent (Carlsen, 2003).

By 1998, 64 per cent of those still working in the agricultural sector lived in poverty; this is contrasted to a pre-NAFTA 1989 level of 54 per cent. Furthermore, by the same year, the overall campesino(rural people) poverty rate had increased to 82 per cent from 79 per cent in 1994 (Anderson, 2004). While Jordan and Sullivan (2003) of the Washington Post correctly acknowledge that this can be partially attributed to population increase, they also emphasized that population growth is nothing new in Mexico and that the lack of consideration for it in NAFTA is further evidence of the poor foresight regarding non-trade ramifications. Despite promises of jobs elsewhere to recoup to the rural losses, these jobs simply have not been created fast enough to replace those lost in the agricultural sector (Carlsen, 2003).

NAFTA has been particularly hard on the Indigenous portion of the agricultural sector. Making up roughly two-thirds of the rural poor, despite being only ten per cent of the overall population, Indigenous peoples have disproportionately, and severely, suffered from the impacts of NAFTA’s agricultural liberalization (Miller & Shannon, 2002). Even in cases where non-agricultural jobs have been created or agricultural positions reformed, Murillo explains that Indigenous peoples have typically resisted any change due to their land-culture relationship which, ibound up as a key element of their identity, creates an aversion to cash-crop farming and migration (personal communication, April 28, 2006). However, NAFTA is not concerned with cultural attachments to potential commodities, and its push for competitive single-crop farming only further marginalizes the Indigenous peoples. Unable to gain any sort of government support without adapting NAFTA principles, they are left with only one choice; either increase income through export-cropping, supported through revamped government funding (SEDESOL, 2005; F.N. 2006), or survive at a subsistence level without government support. There is no middle ground.

The case of corn best illustrates this clash of cultural understandings. As Henrique and Patel (2004) note,

Since many of the poorest people in Mexico engage in corn production, it serves as a barometer for the condition of the most marginalized groups in Mexican society. After ten years of NAFTA, results show that the poorest have fared exceptionally badly. (p. 1)

Corn farmers make up 40 per cent of all farmers in Mexico. The crop, which originated in Mexico some five thousand years ago, is a major source of sustenance for the campesinos—providing up to 70 per cent of their daily caloric intake. It is one of the main sources of agricultural income, and is critical to the existence of the 56 Indigenous cultures that remain in Mexico and make up 60 per cent of the corn farmers (Miller & Shannon, 2002; Nadal, 2000). Indeed corn is “the backbone of Mesoamerican cultures, many of which are alive today in the thousands of corn-growing indigenous communities across Mexico” (Henriques & Patel, 2004, p. 5). This is evidenced “by the fact that many local languages identify more stages of plant development and a richer plant anatomy than conventional botanical literature” (Nadal, 2000, n.p).

The country continues to produce 41 races and thousands of varieties of corn, many of which, playing significant roles in Indigenous ceremonies and practices, cannot be replaced by genetically modified American yellow-corn imports (Ibid; Carlsen, 2003). However, in the trade negotiations the United States was given the comparative advantage—in other words Mexico was told to phase out its corn production—as the Americans could produce corn more efficiently.[§]Additionally, the American yellow corn and the Mexican White corn were treated as the same item in the NAFTA agreement, despite their separation on the international market and the 25 per cent price differential in favour of white corn (Nadal, 2000).

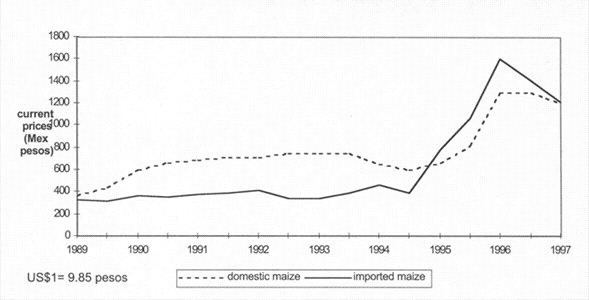

The agreement did recognize the cultural and economic dependence on corn, and allowed Mexico 15 years to phase out the any trade barriers related to the crop, and facilitate the transition to different crops and sectors. Yet, the peso crisis of 1995 and the government’s failure to effectively implement the tariff trade quotas rushed the transition process (as can be seen in Figure 2) effectively eliminating all barriers by 1997 (Ibid; Wise, 2003). The result: in three years Mexico went from a corn exporter to a corn importer. Imports doubled between 1994 and 2000, Mexican corn prices were cut in half, and reliance was fostered on the United States for 23 per cent of its corn, much of which was developed for animal feed, not human consumption (Ibid; Anderson, 2004; Miller & Shannon, 2002; Henriques & Patel 2004; Carlsen, 2003).

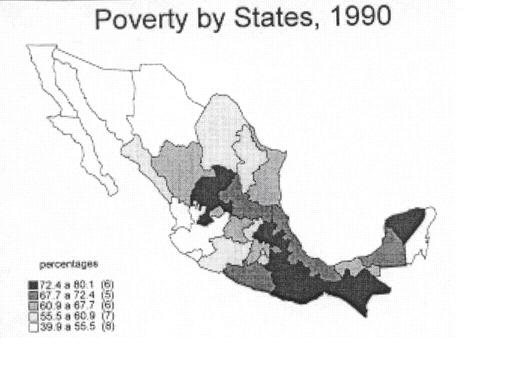

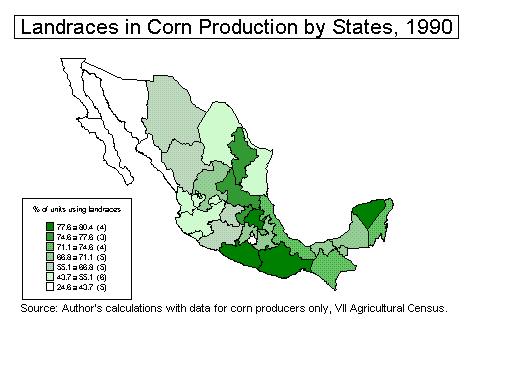

Yet despite the economically devastating circumstances the Indigenous peoples continued to grow the crop and under “inefficient circumstances” no less. Indeed, Nadal (2000) notes that nearly two million corn farmers using collective experience engage “in the art of seed selecting” (n.p.) choosing specimens known for their ability to respond in the environment of the region in question. The terrain is often mountainous with poor soil and irregularly rain fed. It is subject to early frosts, extreme winds, and diverse pests. However, as Figure 3 illustrates, the knowledge of the different specimens allows impoverished Indigenous farmers to grow their sustenance cheaply and sustainably, and Nadal stresses, that this process also plays a major role in preserving the biodiversity of global corn.

Figure 2: Corn’s Transition Period Truncated

Source: Nadal, 2000

As Miller and Shannon (2002) explain, it was economists failing to fully account for the environmental, social and cultural value of corn which impeded their inability to predict why their clear economic logic could not persuade Indigenous peoples to switch crops. This same failing now threatens to undermine the delicate process of subsistence, sustainability and maintenance of biodiversity in addition to the traditional economic and cultural existence of Mexico’s Indigenous peoples. As the next section will discuss, this threat is further exacerbated when the Indigenous people, unable to survive in the new agricultural context are forced to leave their homes in search of more income.

Figure 3: A Comparison of Poverty and Corn

Source: Nadal, 2000

Community stressors and Indigenous Migration

“Rural people are not only poor but they are also getting poorer. The only option for many for many is to leave their homes in search of work in large cities or across borders.”

— Miller & Shannon, 2002

”Corn, Free Trade, and Crossborder Organizing”

With falling wages and raising produce prices the campesinos households are increasingly dependent on external sources of income causing stress both within the community and at the Mexico-US boreder. In 2004, 80 per cent of them had at least one member outside the community on whom they depended for remittance income. This translated into an average of 44 per cent of total household income being derived from non-agricultural sources (Henriques & Patel, 2004). Some families and indeed whole regions have become dependent on this form of income. While some of the money is reinvested into the community for job creation, the continuous down-spiral of the agricultural sector, the ever-growing population and the past economic successes of migration continue to encourage and facilitate the outflow.

With NAFTA causing the loss of nearly one million Mexican jobs in just its first year, remittances have reached record levels, even exceeding the country’s oil revenue. Add to this that there are less than one third of Mexicans working in formal sectors of the economy and there is no sign that the migration surge is going to decrease in the near future (Escobar, Hailbronner, Martin & Meza, 2006). Indeed, under NAFTA the campo economy and culture is collapsing. As Jordan & Sullivan (2003) note, “people are bailing out of the countryside as if it were a ship on fire. … Between 400 and 600 people a day are packing up and fleeing to cities or to the United States” (para. 20).

Recalling that Indigenous peoples make up roughly two thirds of all campesinos and understanding that they also account for the poorest portion (SEDESOL, 2005) we can abstract their participation in this consistent and damaging outflow. Indeed, whole communities of Jornaleros Agrícolas have formed. This term, once meaning simply landless agricultural labourer, has taken on a new meaning in the post-NAFTA climate and “migrant” is now added to the list of adjectives to describe this occupation (Murillo, personal communication April 28, 2006). These communities, the majority of which are Indigenous, exist almost without men (SEDESOL, 2005). In the Náhuatl community of San Cristóbal/Xochimilpa, Puebla, those men who remain are either the community authorities or drunks—broken by their experiences in the foreign cultures of the larger cities within Mexico and across the border. The women, left with unofficial control of community-life, as well as jobs of their own to supplement the remittance income, are overstretched and are forced to leave their young children alone in those after school hours and often beyond dinner time. Where before they could turn to community support structures or be there themselves, now there is no one left to turn to and children are often left malnourished and uncared for. (F.N. 2006; Murillo, personal communication, April 28, 2006).

While this problem certainly exists in Mestizo communities as well, the impact in the Indigenous population as a whole is far more serious, as only 18 per cent of Mestizos are campesinos in comparison with at least 67 per cent of Indigenous peoples (Miller & Shannon, 2002; CDI 2004). However, a more direct impact can be seen if we pull our attention away from the plight of the south and look toward the Mexican-US border where a wall is being built in response to the unpredicted increase of post-NAFTA Mexican migrants. The wall which will include nearly 200 surveillance cameras and 24-hour floodlights will divide and disrupt cross-border peoples such as the Tohono O’oodham and the Yaqui who lay claim to sacred sites and ancestral lands in both Mexico and the United States. Through the construction of the wall the Tohono O’oodam and Yaqui say the American government is disrupting burial sites, denying free passage on traditional lands, and militarizing the area without consultation with affected peoples (Norrell, 2004).

According to Jimmbo Simmons (Norrell, 2006), a Tohono O’oodham and a member of the International Treaty Council, the government anti-migration actions are turning Indigenous against Indigenous. The Tohono O’oodham have outlawed assisting migrants as they cross the scorching desert—despite the often shared Indigenous identity—as the American government has threatened reprisals against those contributing to illicit action. These documented reprisals have included general harassment, intrusion into homes, holding people at gun point and general disrespect such as throwing garbage on sacred sites (Norrel, 2004). However, Simmons remarks on the hypocrisy of the decision saying that “we who were once oppressed, are ever increasingly becoming the oppressor” (Norrell, 2006, p. 1). American Indigenous peoples have called for a halt to the military presence on their ancestral homelands equating the government actions to “psychological oppression and terrorism.” Indeed Simmons says, “the Border Patrol is a death squad. They are operating like they do in Central and South America, because no one can hold them accountable” (ibid, p. 3).

Indeed the increased migration since NAFTA exacerbates the challenges and struggles faced by Meztisos and Indigenous peoples alike. The problem is NAFTA has disproportionately increased the negative impacts on Indigenous communities in relation to the Meztiso communities by combining the general increase of migration (and the stresses on community that presents), with the neoliberal development programs created to operate parallel to and in support of the agreement, which attack the cultural existence of Indigenous peoples. Furthermore, in the inability of the agreement to create jobs as fast as it destroyed them, it increased migration; this lead to the American reaction of the wall and the Indigenous infringements that accompanied it. As we will see in the next section, attacks on Indigenous groups are not limited to by-products of other policies like the anti-migration wall. Rather NAFTA has inspired specific attacks on Indigenous identity and even their very existence.

Fighting for Culture: Human Rights Abuses in Chiapas

“NAFTA ‘is a death certificate for the Indian peoples of Mexico, who are dispensable for the government of Carlos Salinas de Gortari.”

– from one of the first comuniques by the EZLN, 1994

Harvey,1994, p.7

Unfortunately human rights issues are not limited to the NAFTA-fuelled increased migration. Returning our examination back to the south, human rights abuses run rampant. While NAFTA as a trade agreement is not directly responsible for these abuses, it has played a role and it would be remiss to not discuss it. As Henriques & Patel (2004) attest:

Mexican trade liberalization was accompanied by national policy revisions that did away with government support programs and instead focused on increasing export-led growth. It is therefore analytically very difficult to attribute negative impacts exclusively to any particular free trade agreement. (p. 1)

However, there is a very clear link. The Zapatistas marched on San Cristóbal on 1 January 1994 to protest the signing of NAFTA. They did so because they viewed the agreement as a symbol and breaking point of a destructive liberalization process that had begun with the GATT, and secondly to call attention to the increased plight of the Indigenous peoples under this new agreement (Global Exchange, 2005). The battles that followed were in opposition to (in the case of the EZLN) or defensive of Mexico’s neoliberal policies. NAFTA is the metaphorical flag for the government’s army.

Thus while NAFTA itself is not the cause of the human rights abuses that have continued since 1 January 1994, the government continues to fight its subversive war in order to protect the very ideals that NAFTA embodies. With this in mind we can conclude our examination of the effects of NAFTA on Mexico’s Indigenous peoples with a brief discussion of the human rights situation since 1994. As has been argued throughout this paper, the marginalization that Indigenous peoples have suffered since the country’s creation, has only worsened through the implementation of NAFTA.

The IAHRC (1998) outlines a series of obligations of the Mexican state toward the Indigenous communities including participatory planning; management and evaluation in public policy issues such as health, education, natural resource management, development; and the preservation and protection of the respective cultures and traditions. Mexico’s National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (CDI, 2004) echo’s this statement with principles recognizing a multiethnic and pluricultural Mexico and the need for consultation, protection from social exclusion and discrimination, tolerance, intercultural dialogue, respect for differences and a sustainable use of resources, to name a few. However, NAFTA’s neoliberal economic reforms are in direct contrast to any sort of respect for cultural differences or sustainable use of resources as previous examined cases such as corn and the border wall have shown.

Indeed, NAFTA is contributing to a process of cultural degradation despite government commitments to the contrary. Murillo (Personal communication April 28, 2006) explains that cultural identity is increasingly threatened. Sheargues that the NAFTA-encouraged migration exacerbates the general disregard for Indigenous culture and contributes to a process of desindigenesación (deindigenization) where many Mexican Indigenous people, especially those closer to the border, are rejecting their identity. She recalls spending eight months in 2005 trying to identify just four or five families which would self-identify as Indigenous in Cholula, Puebla (a south-central state no less).

Murillo argues that migration is a particular contributor to this desindigenesación. Not only do Indigenous migrants suffer racism from Mestizos and Americans, which often throws them into the dark circles of depression and alcoholism that now plague the Jornaleros Agrícolas communities, but migration also forces them to break with their culture. As Landín notes:

An Indigenous person who moves to the city will no longer be able to think the same because they loose their connection with mother earth when they don’t work with it every day. They don’t feel it or dream about it. In the city there is no direct relationship. (personal communication, May 14, 2006)

These concerns of cultural degradation have been most strongly voiced in Chiapas by the EZLN. In this state Harvey (1994) explains the unrest after NAFTA, as the culmination of a historical lack of consultation with campesinos regarding land, agricultural, and social reform of their rural domain. The EZLN made this clear throughdemands for respect of Indigenous cultures and values through autonomy and economic policies that would benefit Mexico’s majority—not just its elite (Global Exchange, 2006). While attempts were made to quell this resistance through the San Andrés Accords of 1996, subsequent inaction by the government resulted in the increased militarization of Chiapas and fervent persecution of suspected EZLN sympathisers who were considered a threat to the Mexican state.

It should be noted that in addition to militarization, infrastructure and general development investment also escalated in Chiapas after the dismissal of the Accords, but the very nature of the investment serves to underscore the complete disregard and/or misunderstanding of the Indigenous communities by the government. Harvey (2001) explains that “attempts to mediate the effects of this modernization strategy,” in which NAFTA is included, “were precisely designed to limit development alternatives to the dictates of international markets” (p. 1047). The government continues to institutionalize neoliberal policies into development planning, undermining Indigenous attempts at cultural preservation by providing aid and infrastructure as rewards for adopting neoliberal lifestyle changes like cash-crop farming.

This can be seen in a case documented by the IAHRC where three separate groups of Indigneous peoples in Chilon, Chiapas who previously held shared land titles, were divided by national policies in place to encourage NAFTA-style refoms. One of the groups opted to take part in the new export-based economy and in 1995 they began to exploit the land for its natural resources with the support of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) and their constitutional amendment to article 27. (This amendment dissolved the ejidos, the communal land ownership model, and paved the way for individual ownership.) The group seized the individual ownership opportunity without consultation with the other two groups despite the historical legal ownership of the land by all three groups and proceeded to levy taxes on the other two groups for continued occupation after the change in title. Murder and property destruction haunted the communities for years to come (Foley, 1995; IAHRC, 1998). What can also be seen in this case study is an age-old government tactic where small concessions, land title and profit from export, are made to desperate groups in order to silence any resistance (Friedberg, 2005).

There are also blatant human rights abuses as a direct reaction to the continued activity by the EZLN. Restriction of movement via harassment and checkpoints remain in place by both the government and the EZLN continue to plague Chiapas (F.N., 2006) The IAHRC (1998) cites human rights violations by security forces “against the life, integrity, freedom and property of the rural and indigenous civilian population” (art. 522). IAHRC further notes that paramilitaries have established an ongoing climate of fear, routinely targeting prominent human rights centers and civilians and massacres are not an uncommon occurrence. The most infamous occurred in 1997 in Acteal where 45 Indigenous displaced persons, including women, children and babies, were slaughtered by paramilitaries allegedly associated with the Mexican government. These are but a smattering of the documented incidences that have occurred since the Zapatista uprising in 1994. As Global Exchange (2005) notes, since 1994 in Chiapas alone, “hundreds have died, tens of thousands have fled their homes and many more have been forced to live their lives in constant fear” (n.p.) while the Mexican government wages its war of suppression.

Though the EZLN does not represent all Indigenous peoples of Mexico it is a strong voice for their struggles against NAFTA and more broadly the neoliberal system that directly clashes with the Indigenous view of land, life, and identity. Rather than try to incorporate these difference into the Mexican political culture as the CDI claims, the paramilitaries and Mexican government continue to suppress them and institutionalize marginalization through policies and agreements such as NAFTA. As this paper has shown, NAFTA by increasing the already dangerous threat to Indigenous peoples’ very economic and cultural survival, has played no small role in this process.

NAFTA’s Role in the Indigenous Crisis

Indeed, the situation of the Indigenous peoples of Mexico is a complex one that extends far beyond the affect of NAFTA in isolation as a trade agreement. Nevertheless, the connection between the agreement and Indigenous plight, however distant, cannot be ignored. NAFTA as an agreement between three states is a product of the global trends toward neoliberalism but it is also responsible for the decisive push of Mexico into this neoliberal economy, even if Mexico was opening its borders before the agreement. NAFTA is responsible for the devastating effects felt by the rural population, such as those in relationship to corn crops, throughout the 1990s and continuing today. NAFTA is responsible for increased migration despite promises of the opposite, and NAFTA certainly did aggravate already tense issues in states like Chiapas which lead to violent protest and oppression.

Though ironically the government touts the historical successes of the Indigenous peoples’ ancestors, namely the Aztecs and the Mayans, as fundamental to Mexico’s history and heritage, the present generation, and indeed any generation of Indigenous peoples since colonization, have been the poorest, most marginalized and vulnerable groups within the country. Obviously, NAFTA cannot be held solely responsible for this but for an agreement that promised to lift the nation out of poverty, the ramifications of this trade agreement, however direct or indirect, must be held to account. NAFTA has increased the negative impacts on Indigenous society, cultural and livelihood. Indeed NAFTA is but another notch in the belt that is ever-tightening around the Mexican Indigenous peoples, bringing them closer and closer to strangulation.

References

Anderson, Sarah. (2004). “A decade of NAFTA in the United States and Mexico”. Canadian Dimension. 38(2). Retrieved August 26, 2004, from Academic Search Premier database.

Améndola, R., Castillo, E. & Martínez, P. (2005). “Mexico.” Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profiles. Food and Agriculture Organization. January/February. Retrieve April 22, 2006 from http://www.fao.org/ ag/agp/agpc/doc/counprof/mexico/mexico.htm.

Bacon, D. (2004). “NAFTA’s legacy: profits and poverty”. San Francisco Chronicle. January 14 2004. A-23. Retrieved November 7, 2006 from http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/chronicle/archive/2004/01/14/EDG3548NNO1.DTL.

Carlsen, L. (2003). “The Mexican Experience and Lessons for WTO Negotiations on the Agreement on Agriculture.” Americas Program, International Relations Center. Retrieved November 7, 2006, from http://americas.irc-online.org/am/1877.

Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de las Pueblos Indígenas (CDI). (2004). Retrieved April 20, 2006, from http://www.cdi.gob.mx.

Escobar, A., Hailbronner, K., Martin, P., & Meza, L. (2006). “Migration and development: Mexico and Turkey”. International Migration Review. 40(3). Retrieved October 10, 2006, from Academic Search Premier database.

Foley, M.W. (1995). “Privatizing the Countryside: The Mexican Peasant Movement and Neoliberal Reform.” Latin American Perspectives. 84(22). Retrieved November 12, 2006 from http://lap.sagepub.com.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/cgi/reprint/22/1/59 via University of Alberta access.

Friedberg, J. (2005). Granito de Arena. Baltimore, USA: Las Américas Film Network.

Jordan, M. & Sullivan, K. (2003). “Trade brings riches, but not to Mexico’s poor”. Washington Post. March 22, 2003. Retrieved November 7, 2006 from http://www.globalpolicy.org/ socecon/ffd/2003/0322mexico.htm.

Harvey, N. (1994). “Rebellion in Chiapas: Rural Reforms, Campesino Radicalism and the Limits to Salinismo.” Transformation of Rural Mexico, 5. San Diego, USA: Center for US-Mexican Studies.

Harvey, N. (2001). “Globalisation and resistance in post-cold war Mexico: difference, citizenship and biodiversity conflicts in Chiapas.” Third World Quarterly 22(6).Retrieved November 12, 2006 from University of Alberta Journals Collection.

Henriques, G. & Patel, R. (2004). “NAFTA, Corn, and Mexico’s Agricultural Trade Liberalization.” Americas Program, International Relations Center. Retrieved November 7, 2006, from www.americaspolicy.org.

— (2006).“Mexico Highlights.” Latin America and Caribbean. The World Bank Group. Retrieved April 19, 2006 from http://www.worldbank.org>.

Miller, S. & Shannon, A. (2002). “Corn, Free Trade, and Crossborder Organizing,” Enlaces America & Americas Program, International Relations Center. Retrieved November 7, 2006 from http://www.irc-online.org/americaspolicy/citizen-action/focus/0207corn_body.html

Nadal, Alejandro. (2000). “Corn and NAFTA: An Unhappy Alliance.” Seedling. June. Retrieved November 20, 2006 from http://www.grain.org/seedling/?id=14.

Norrell, B. (2004). “Tohono O’odham and Yaqui: ‘No more walls’,” Indian Country Today. June 20, 2004. Retrieved November 12, 2006 from http://www.indiancountry.com/ content.cfm?id=1090337206

Norrell, B. (2006). “Indigenous Border Summit Opposes Border Wall and Militarization.” Citizen Action in the Americas. Americas Program, International Relations Center. Retrieved November 7, 2006 from http://americas.irc-online.org/amcit/3648.

Preston, Cosanna. (2006). Field Notes. February 4 – 5 & March 9 – 13, 2006. San Cristóbal Xochimilpa, Puebla, Mexico.

— (2005). “Programa de Atención a Jornaleros Agrícolas.” SEDESOL. Gobierno de Puebla. Presentation, 24 May 2005. CD-ROM. Viewed April 24, 2006.

— (2005). “Programs in the Americas: Chiapas.” Global Exchange.Retrieved November 15, 2006 from http://www.globalexchange.org/countries/americas/mexico/chiapas/

— (2006). “Programs in the Americas: Mexico,” Global Exchange.Retrieved April 19, 2006 from http://www.globalexchange.org/countries/americas/mexico.

Ross, John. (2001). “Law widens racial divide.” Latin America Press. May 28, 2001. Retrieved April 20, 2006 from http://www.latinamericapress.org/article.asp?IssCode=&lanCode=1&artCode=2234

— (2000). “San Andres Accords.” Crisis in Chiapas. Retrieved March 2, 2006 from http://www.jaguar-sun.com/chiapas.html.

Scott, J. (2004). “Poverty and Inequality”. NAFTA’s Impacts on North America: The First Decade. Washington, USA: The CSIS Press, p. 307-337

— (1998). “The Situation of Indigenous Peoples and Their Rights”. Report on the Situation of Human Rights in Mexico.Inter-American Human Rights Commission. 7(1). Retrieved November 18, 2006 from http://www.oas.org/main/main.asp?sLang=E&sLink=http://www.oas.org/ OASpage/humanrights.htm.

*Pacha Mama is a Náhuatl term for mother earth which embodies the intrinsic connection between the Náhua people and the land. The Náhua’s are also decedents of the Aztecs.

[*](personal communication, May 14, 2006)

[†]Extreme poverty is defined by the World Bank as living on less than $1 per day. However, one lives in poverty when he/she cannot afford to buy the resources they need to live. The exact amount varies from country to country depending on the cost of living.

[‡]All poverty percentages were obtained from “Mexico Highlights.” Latin America and Caribbean. The World Bank Group. 2006. . (Accessed 19 April 2006).

[§]Mexico averages 1.7 tons of corn per hectare while the US averages 7 tons. The average time in Mexico to produce one ton of corn is 17.8 days while it takes the US just 1.2 hours (some modern irrigated farms in N Mexico compare to this). Finally, 80 per cent of Mexican corn is rain fed and unmechanized due to steep slopes and poor soil while virtually 100 per cent of American corn is irrigated and mechanized (Henriques & Patel, 2004)

—

Written by: Cosanna Preston

Written at: University of Alberta

Written for: Dr. Julián Castro-Rea

Date written: 30 November 2006

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Wind Energy in Mexico: Who Benefits?

- The Role of Global Governance in Curtailing Mexican Cartel Violence

- Populism and Extractivism in Mexico and Brazil: Progress or Power Consolidation?

- Transforming Global Food Systems: Centering Indigenous Land Returns

- Piracy in the Southern Gulf of Mexico: Upcoming Piracy Cluster or Outlier?

- Racism and the Politics of Fear at the US-Mexico Border