As of the 1980’s an apparent trend can be highlighted whereby the world’s developing countries have been compelled, to adhere to the orthodox neoliberal confidence in free trade. As a result of the entrenchment of this orthodoxy, its principles have been transplanted into policy advice and action in developing countries. These have been manifested through the implementation of the Washington Consensus polices, which are loosely defined as neoliberal macroeconomic polices, minimal state intervention, trade liberalization and a dependency on the market to allocate scarce resources efficiently. In his book The Lexus and the Olive Tree, Freidman (2000) calls these neoliberal economic polices the Golden Straitjacket, which despite having a one size fits all outlook, are the only measures from which developing countries can fully take advantage of globalization. Quintessentially those who advocate the orthodoxy – namely the developed economies and international institutions such as the World Bank – promote the notion that through outward orientated policies, the developing economies will foster their own economic growth and therefore development. It is important to understand, that the policy makers in the developed economies firmly believe that it is through this reasoning, which allowed their own development. It is the intention of this paper to evaluate this belief by assessing the following statement, ‘The most successful developing economies are characterised by greater trade openness.’ This paper agrees with the opinion that trade is an essential tool, which helps developing economies industrialise. However by using case studies, empirical data and analysing the adopted polices of the successful developing economies, this paper will support the argument that the most successful developing economies, developed under a more protectionist environment. Having completed this evaluation, the paper will then look at the policy implications of the conclusions made. It will argue that, “free trade is not passé” (Krugman, 1987, p, 132) but it can not be asserted as the pre-eminent policy by which developing economies are expected to develop under.

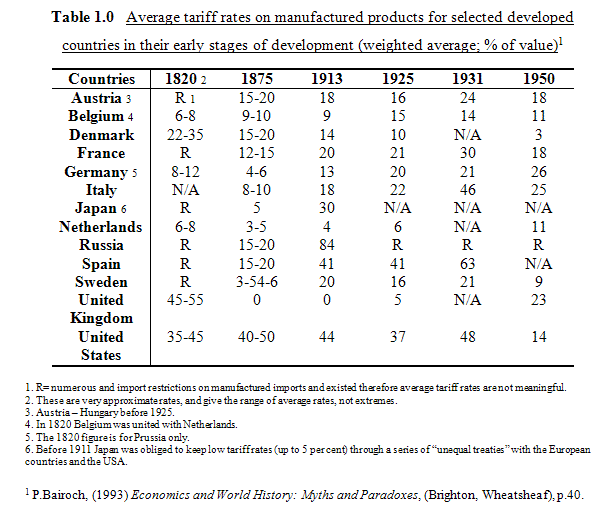

In Kicking Away the Ladder: Development Strategy in Historical Perspective H.J. Chang puts forward a historical perspective on the issue of whether the most successful developing economies were characterized by trade openness. Intrinsically his argument is a challenge to the prevailing, “official history of capitalism” (Chang, 2002, p. 12) which accentuates that both Britain and the USA are the homes of free market, free – trade capitalism. Chang argues that in fact this is not the case, but what the neoliberal advocates would like the developing countries to believe, so that their argument for pushing forward the proposals of trade liberalization upon the developing economies are justified. Though he is careful in reiterating the fact that the neo-liberalists do not do this on purpose, instead Chang emphasizes that they commit to these polices of free trade, “in the honest but mistaken belief that those are the routes their own countries took in the past to become rich” (Chang, 2007, p. 17) Through Chang’s work two major case studies are provided through which it is possible to illustrate that the most successful developing economies are not characterised by trade openness. The first of these is Britain. Bhagwati (1985) points out nineteenth century Britain, as being the prime example of the industrial success of laissez–faire policy. Her success not only enforced the ascendancy of free market and free trade policies, but by the 1870’s had established a new liberal world economic order which was distinguished by, laissez-faire industrial police at home and low barriers to the international flow of goods, capital, and labour. Yet as early as 1841 the German economist Friedrich List had criticised Britain of having a hypocritical trading policy, by insisting on one hand free trade to other countries while on the other hand attaining her own economic ascendancy through a system of high tariffs and extensive subsidies. Quintessentially he accuses Britain of having, “attained the summit of greatness, [and then] kick away the ladder by which he has climbed up, in order to deprive others of the means of climbing up after him.”[1] Though List is writing in the mid 1800’s, his views are a clear description of the actions of the developed economies in the present day. List’s accusation of Britain’s behaviour can be illustrated through her trade policies. As Table 1.0* emphasizes, before Britain endorsed free trade in the mid-nineteenth century, she had as far as the 1820’s extremely high tariffs on imported manufactured goods. This protectionist stance began to take effect under the premiership Robert Pole (1721-1742). Under Pole Britain shifted her trading policy away from one which was set to generate government revenue, to one which promoted manufacturing industry. In doing so he clearly believed that public welfare would be enhanced and therefore enacted legislation to, “protect the manufacturing industry, subsidize them, and encourage them to export” (Chang, 2002, p. 23). Through this legislation import tariffs were imposed on foreign manufactured goods while at the same time tariffs on those raw materials required to enhance the growth of the manufacturing sector were cut. Furthermore export subsidies were promoted to serve as an incentive for the export of domestically manufactured goods. Additionally regulation was imposed on the quality of the manufactured goods, so that the British reputation would not be damaged in foreign markets (Chang 2002, 2005, 2007). These interventionist, “industrial, trade and technological (ITT)” (Chang, 2005, p. 107) polices carried on for more than a century, allowing British manufacturing industries to catch up and advance ahead of their counterparts. These not only included her rivals on the Continent but also the colonies she had conquered, who despite not having the industrial capacity of Britain were competitors in sectors such as the textile industry, as they produced these goods at lower production costs. Britain countered this by banning competitive exports from these colonies, while at the same time constraining the colonies to remain as the exporters of primary production commodities. This ensured that the colonies did not develop, as they remained labour intensive industry exporters. This clearly shows that Britain developed under protectionist regimes which even Adam Smith (1991), recognised as he understood that without the high levels of state protection British manufacturers would not have been technologically proficient and therefore internationally competitive. He however encouraged free trade when he wrote The Wealth of Nations in 1776, because he realized that it was in the best interest of Britain to do so, otherwise continued state intervention would only encourage inefficiency and complacency.

The second case study to be evaluated is the USA, which this paper will argue developed through the launch of a large scale infant industry promotion strategy. The notion of protecting US industries in their infancy from foreign competition was ascertained in 1791, by the Finance Minister Alexander Hamilton. In his Report on the Subject of Manufacturers he promoted a course of action which would ensure that US industries would be allowed to develop and become internationally competitive. It is crucial to understand, that though Hamilton endorsed the anti trade liberalization measures such as protective tariffs and import bans, he made it clear that these policies should only last as long as the industries have not developed to the stage, where they could effectively compete with foreign competition on the international markets. Hamilton’s policy initiatives provided the economic blueprint for US economic policy up until the end of the Second World War. As Table 1.0* shows the USA had the highest tariff rates on manufactured goods in the world up until the 1940’s, which provided its developing industries the incentive to propel themselves from the high labour intensive agrarian industry to the world’s greatest industrial power. Hamilton never saw his programme for US industrial development fully implemented, as it occurred under the presidency of Abraham Lincoln (1861-1865). Under Lincoln’s tenure a growing debate ensued between the agricultural Southern States, who were advocates of free trade policies and the industrialized Northern States, who sought state protectionism to allow for American industry to expand. This friction in the USA boiled out into contributing to the American Civil War, but under Lincoln US industrial tariff rates soared up to 40%-50% and remained so until the end of the 1940’s. According to Bairoch (1993), it is during this period that America experienced a rapid growth rate. It was only after the Second World War when US industry had firmly established its global supremacy, that the USA reduced its tariff rates and began to champion the cause of free trade, as Britain had done earlier. Yet it can still be argued that though the US has reduced its tariff rates, it still protected her industries through non-tariff mechanisms such as the public funding of R&D. Up until the mid-1990’s the US federal government, “funding accounted for 50-70% of the country’s total R&D funding” (Chang, 2007, p. 56). Without such state intervention the US would certainly not have been able to maintain its global technological lead in key industries such as aerospace.

This paper has shown that two biggest global advocates of trade liberalization in the modern era, developed under different circumstances. Firstly Britain and then the USA developed under a high level of state intervention which imposed protectionist measures such as tariffs on manufactured imports. Therefore this is clear evidence that the ‘most successful developing economies are not characterised by trade openness.’

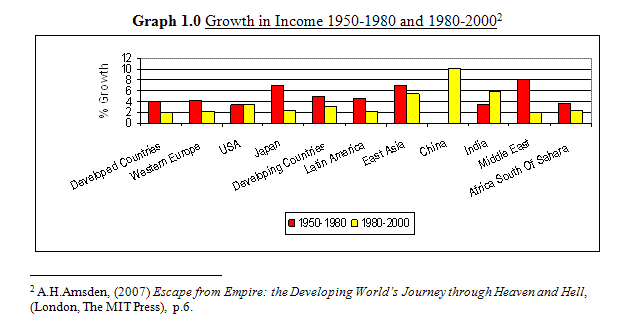

This paper will now evaluate whether the most successful developing economies in the modern era (1950- present day) are characterized by greater trade openness. This era can be defined by Amsdens (2007) two American Empires. The first American Empire (1950-1980) saw a more lenient attitude towards the developing world’s adoption of trade liberalization. A key reason for this was due to US concern that the developing economies were prime targets for the spread of communism. Generally speaking this era has been epitomised by high economic growth rates, in developing countries as Graph 1.0* shows. Meanwhile the second American Empire (1980-present day), has been distinguished by a more ruthless US attitude, in its push towards opening up the markets of developing economies and this has largely seen a lower growth rate for developing economies.

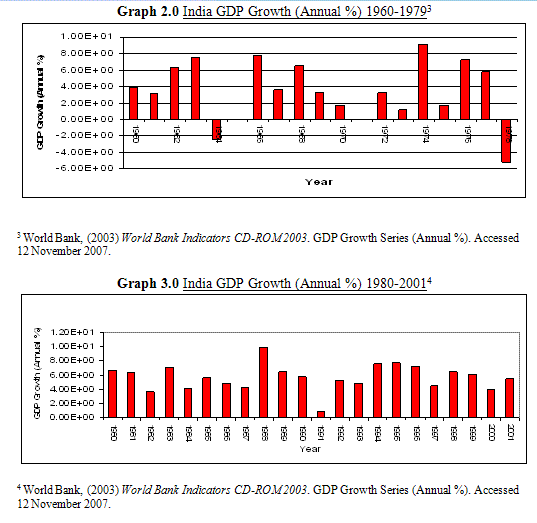

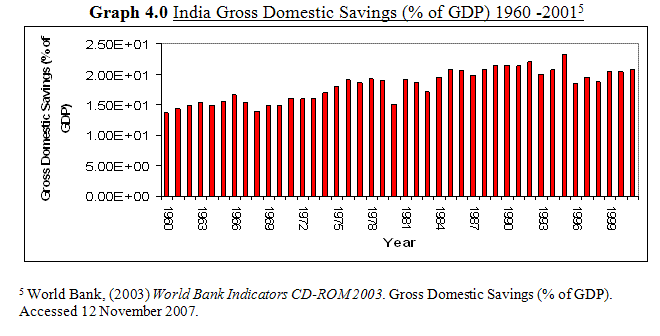

Graph 1.0* highlights some interesting points. Firstly it emphasizes that the Developing Countries, had higher income growth rates during the first American Empire than in the second American Empire. Seeing that during this period the developing economies generally endorsed the role of the state in regulating the market, these income growth rates prove wrong the conclusions made by neoliberal advocates such as Dornbusch (1992), that the economic performances of the developing economies during this period were poor. Secondly like Graphs 2.0 and 3.0*, it shows that the late developing countries such as India had a higher income growth rate in the second epoch than the first, which the neoliberal advocates put down to the trade liberalization reforms promoted during this period in India. However this is not the case. The higher income growth rates in India can be accounted for by the previous governments polices of assisting small scale firms. While these polices were promoted at the expense of rapid industrialisation, it allowed for output to increase as industries such as the software services boomed with the help of government investment, in areas such as electronics and telecommunications. Furthermore India’s growth rate was fuelled by savings rate which rose as high as 23% of GDP as shown in Graph 4.0*. In compliance with the Harrod-Domar growth model, savings along with investment and technological change are the key variables in determining economic growth, as they are all factors which lead to an outward push of the economy’s production possibility frontier (PPF). What is crucial to understand is that India’s development plan, followed in the footsteps of the Latin American and East Asian economies before the 1980’s by committing to an infant industry promotion strategy, as Britain and the US had done during their years of development. A distinctive feature of these economies was the government’s promotion of, “Import Substitution Industrialization (ISI)” (Lall, 2005, p.97) to assist economic growth and therefore development. Trade liberalization is founded upon the neoliberal principle of David Ricardo’s comparative advantage, which has been expanded upon by the work of Heckscher-Ohlin. It exists when an economy is able to produce a good more cheaply relative to other goods produced domestically, than another economy. Therefore in terms of trade theory, neoliberalists argue that economies will find it mutually advantageous to trade if the opportunity cost of the production of goods differs. Taking into consideration the assumptions of factors of endowment, comparative advantage as explained by Ricardo is a persuasive trade theory. However realistically comparative advantage does not allow for development to occur in a developing economy. This is because comparative advantage installs an attitude that an economy should only trade in the sector which they are able to produce cheaply, and therefore specialize in it. For the developed economies this constitutes as being high tech industries, however for the developing economies this normally evolves around labour intensive industries such as agriculture. Seeing that the individuals working within this sector are subsistence farmers, by enforcing them to remain in this industry due to comparative advantage, they are unable to alleviate themselves out of poverty. At a macro level the consequences for the economy is that it’s economic growth will remain relatively low, therefore it cannot develop as it does not have the financial capita to diversify its economy into mid tech industries. Many developing economies in East Asia and Latin America overcame this problem through ISI, as it stimulated growth through entrepreneurship. In essence businesses were encouraged to produce goods and services that the domestic market were importing from abroad. With the security of government protection in the form of, “price distorting polices [such as] subsidising declining industries, targeting and subsidising credit to selected industries and establishing financially supporting government banks” (World Bank, 1993, p.5) as well as stable domestic demand, entrepreneurs were given the incentive to replace these imported goods with domestically produced goods. These goods generally tended to be luxury goods such as automobiles, therefore in order to make these luxury goods the country had to develop a domestic infrastructure e.g. steel industry, which enabled business to do so. There are many benefits to this strategy. Firstly it reduces the county’s balance of trade deficit, as there is a control on imports and therefore the outward flow of capital. Secondly with this extra capital remaining in the economy in the form of savings, it can be invested into projects which promote economic growth. This means the saved capital can be in the short run invested in importing the required technological infrastructure and know-how, to produce ISI goods. This stimulates economic growth and development as the economy is outwardly pushing its PPF as well as diversifying in what it is producing. Thirdly it will have a Keynesian multiplier effect, as the increase in demand will create jobs and as individuals increase their human capital, there will be an increase in income which will be spent back into the economy. Overall the economy is developing, as it is no longer sustaining itself on subsistence farmers working in the agricultural industry. The policies of the Korean government typified ISI strategy in the developing world, during the first American Empire. For example industries were selected by the government which would encourage economic growth. As a result state owned enterprises such as POSCO, and other privately owned business were given government protection in the form of import tariffs, which were as high as, “29.7 per cent in 1977” (Edwards, 1993, p.1360) and low borrowing rates from the Korean Development Bank, which increased profits and therefore the amount of earnings retained. Furthermore the Korean government had absolute control over scarce foreign exchange, which instead of being utilised on importing luxury goods, vital machinery and other industrial inputs were imported, therefore providing the infrastructure necessary to allow infant industries to grow. Importantly to counter the possibility of corruption and market inefficiency, the Korean government like the USA ensured that business, who received government support, had to in return maintain a set standard in terms of production and quality of production. Through this development plan Korea was able to international competitiveness, therefore allowing heavy industry to become Korea’s leading exporter. Quintessentially for the developing economies ISI was a more cautious and more statist road to achieving comparative advantage (Deraniyagala and Fire 2006). This has allowed countries like South Korea and Brazil to now compete against the entrenched big business of developed countries, who had for years been earning monopoly rents.

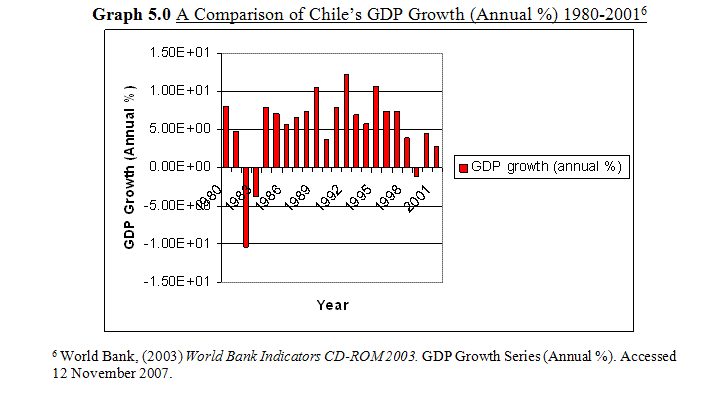

The second American Empire has been characterized by a resolute push towards free trade, and on the whole the successes of the developing economies have been few and far between. The one repeated success case has been Chile, which has despite continued IMF pressure achieved a growth rate as high as 12% as shown in Graph 5.0*> by simply not adhering to all of the prescribed rules of the Washington Consensus. Chile did not open its markets fully; instead she taxed inflows of capital which helped diminish the effects of the currency crisis which affected Latin America in the 1990’s. Furthermore the Chilean government selectively privatized the economy, and instead promoted state owned companies to the extent that, “20 per cent of exports still come from one government – owned enterprise CODELCO” (Stiglitz, 2005, p.16). Furthermore the social democratic governments developed the social welfare of the economy by spending heavily into education and health provision, which were financed by her growth at not by debt financing.

Compared with developing countries such as Mexico who have prescribed to the tenets of the Washington Consensus, and have performed badly since the 1980’s, the success of those economies that followed the infant industry promotion strategy merely reiterate the argument made throughout this paper, that the most successful developing economies are not characterized by trade openness.

Having established that the most successful developing economies have not developed under trade openness, this paper will now suggest a limited policy proposal, based on the conclusions of this paper. Trade liberalization is the objective which developing economies should strive for at the end of the day. However in order to achieve this, firstly a conceptual outlook has to be taken and secondly free trade should not be the development strategy. This is because comparative advantage pre-requisites that economies should only develop goods for trade in which they have an opportunity cost. This would render the developing economies to remain in sectors which offer low economic growth and as a result low living standards. However it is important to understand that trade is an important tool for development. Economic development is about diversifying the economy away from labour intensive industry such as agriculture to a more technological advanced economy. In order to do this a developing economy needs to import the technology, which can only be financed through foreign currencies. A government can control the outflow of foreign currency by restricting the imports of luxury goods, but an important accumulator of foreign currency is the exporting of the countries goods. For example Korea financed her drive for industrialisation by exporting simple garments which it could produce cheaply. Therefore one can argue that trade is important for development, but this does not mean free trade from the outset.

A crucial component for the developing economies in their development plan is the role of the state. Free trade places its trust in the market to allocate resources efficiently. Yet this allocation may not be fair and equal. For example market adjustments as a result of comparative advantage stipulating which sector an economy should specialise in, causes high levels of unemployment. In a developed state with a strong welfare system, those who have been rendered unemployed can be guaranteed unemployment benefits. These are virtually non-existent in developing economies. The state is therefore a key mechanism which amends the inefficiencies of the market. This is manifested in the form of infant industry protection, which sees the government protect through tariffs, selected state-owned and private enterprises which are enrolled in projects that promote economic growth. Free trade advocates argue that by imposing such regulations, it stagnates the competitiveness of the economy. Yet there are benefits for having such mechanisms in place. For example by protecting the infant industries the government is providing a better chance for these industries to build up their international competitiveness, and the protective barriers will be reduced once these industries have reached a stage were they can compete with developed economies. Furthermore through tariffs, revenue is provided for funding fiscal expenditure on welfare issues such as health and education, in the absence of a low tax base. However in order for this to succeed, it is crucial that the developing economies not only prevent corruption and market inefficiency, but also have a measured approach to knowing when its industries have reached international competitiveness.

To help facilitate this development action, the international trading system should be more conducive to asymmetric protection. Currently the developed economies are driving for the proliferation of trade liberalization through multilateral economic organizations such as the WTO. Yet this drive is having a damaging effect on the developing economies international treaties and bilateral agreements are limiting the, “development space” (Wade, 2005, p.80) of the developing economies. The current commitment to trade liberalization is in fact limiting the ability of developing economies to pursue the industrial and technological policies they need in order to develop, and more importantly the types of polices which the developed economies developed under. For example development is not only about securing the physical infrastructure to develop, but also the know-how. Developing economies have been disadvantaged in this respect as the, “trade-related intellectual property rights (TRIPS)”(Bhaduri, 2005, p.70) have meant that developing economies will find it more difficult to learn about their newly imported technology, as the developing economies hold patronage rights over them. The international trading system should therefore take a step back and allow developing economies to use tools such as foreign investment regulation which will allow them to develop.

In conclusion this paper has evaluated the statement that, ‘The most successful developing economies are characterised by greater trade openness.’ Through the use of case studies, empirical data and the analysis of the most successful developing economies trade polices this paper has concluded that this statement is in fact not true, and that the opposite is in fact the case. It has found that the modern advocates of trade liberalization, namely Britain and the USA, in fact developed under a more protectionist environment. Furthermore those successful developing economies in the modern era, such as Brazil and Korea have followed more protectionist polices in their own development plans. Having established this, the paper then looked at what possible strategy developing economies could use. It concluded that due to the failure of free trade (not trade) as a development plan, developing economies should promote polices which protect their industries therefore allowing them to develop, until they reach a standard of international competitiveness.

Appendix

Bibliography

A.H.Amsden, (2007) Escape from Empire: the Developing World’s Journey through Heaven and Hell, (London, The MIT Press).

A.Bhaduri, (2005) ‘Toward the Optimum Degree of Openness’ in Gallagher. K. P. (ed.) (2005) Putting Development First: the Importance of Policy Space in the WTO and International Financial Institutions (London, Zed Books).

J.Bhagwati, (1985) Protectionism, (Cambridge and Massachusetts, The MIT Press).

P.Bairoch, (1993) Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes, (Brighton, Wheatsheaf).

World Bank, (2003) World Bank Indicators CD-ROM 2003. GDP Growth Series (Annual %), Taxes on International Trade (% of Current Revenue), Gross Domestic Savings (% of GDP). Accessed 12 November 2007.

World Bank, (1993) The East Asian Miracle: Economic Growth and Public Policy (New York, OxfordUniversity Press).

H.J.Chang, (2002) Kicking Away the Ladder: Development Strategy in Historical Perspective, (London, Anthem Press).

H.J.Chang, (2007) Bad Samaritans: Rich Nations, Poor Policies, and the Threat to the Developing World, (London, Random House Business Books).

H.J.Chang, (2005) ‘Kicking Away the Ladder: “Good Policies” and “Good Institutions” in Historical Perspective’, in K. P. Gallagher (ed.) (2005) Putting Development First: the Importance of Policy Space in the WTO and International Financial Institutions (London, Zed Books).

R.Dornbusch, (1992) “The Case for Trade Liberalization in Developing Countries,” The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol.6, No.1.

S.Edwards, (1993) “Openness, Trade Liberalization, and Growth in Developing Countries,” Journal of Economic Literature, Vol.31, No.3.

S.Deraniyagala & B.Fine, (2006) ‘Kicking Away the Logic: Free Trade is Neither the Question Nor the Answer For Development,’ in K.S.Jono &B.Fine (ed.) (2006) The New Development Economics: After the Washington Consensus, (London, Zed Books).

T.Freidman, (2000) The Lexus and The Olive Tree, (New York, Anchor Books).

P.R.Krugman, (1987) “Is Free Trade Passé?” The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol.1, No.4.

S.Lall, (2005) ‘Rethinking Industrial Strategy: The Role of the State in the Face of Globalization’ in Gallagher. K. P. (ed.) (2005) Putting Development First: the Importance of Policy Space in the WTO and International Financial Institutions (London, Zed Books).

A. Smith, (1991) The Wealth Of Nations, (London, Everyman).

J.E.Stiglitz, (2005) ‘Development Polices in a World of Globalization’ in Gallagher. K. P. (ed.) (2005) Putting Development First: the Importance of Policy Space in the WTO and International Financial Institutions (London, Zed Books).

R.H.Wade, (2005) ‘What Strategies Are Viable for Developing Countries Today? The Third World Organization and the Shrinking of “Development Space”’in Gallagher. K. P. (ed.) (2005) Putting Development First: the Importance of Policy Space in the WTO and International Financial Institutions (London, Zed Books).

[1] He Continues: ‘Any nation which by means of protective duties and restrictions on navigation has raised her manufacturing power and her navigation to such a degree of development that no other nation can sustain free competition with her, can do nothing wiser than to throw away these ladders of her greatness, to preach to other nations the benefits of free trade, and to declare in penitent tomes, that she has hitherto wandered in the paths of error, and has now for the first time succeeded in discovering the truth.’ F.List in H.J.Chang, (2007) Bad Samaritans: Rich Nations, Poor Policies, and the Threat to the Developing World, (London, Random House Business Books), p.16.

* See Appendix.

* See Appendix.

* See Appendix.

* See Appendix.

* See Appendix.

* See Appendix.

* See Appendix.

—

Written by: Rajpal Singh Ghataoura

Written at: SOAS

Written for: Dr John Di John

Date written: 2008

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Assessing Globalisation’s Contribution to the Sex Trafficking Trade

- TRIPS-Plus Provisions and the Access to HIV Treatments in Developing Countries

- Capitalism and the Rise of New Slavery: From Slave Trade to Slave in Trade

- Are We Entering an “Asian Century?”: The Possibility of a New International Order

- How Does the EU Exercise Its Power Through Trade?

- Are You a Realist in Disguise? A Critical Analysis of Economic Nationalism