How Is The Increasing Convergence of Poverty Reduction Policies Among Global Governance Institutions Manifested? Does This Convergence Signal Better Prospects For Poverty Reduction? Discuss Critically and Illustrate With Concrete Examples.

Arturo Escobar argues that, only with the consolidation of market led capitalism, did systematic pauperization become inevitable (Escobar, 1995). According to Majid Rahnema’s account of the archaeology of poverty, this process of pauperization can be clearly defined into two distinct epochs, of which the Post-Second World War period is a key era in the poverty discourse (Rahnema, 1991). This is because with the globalisation of poverty after 1945, more than two-thirds of the world population were defined as poor. A consequence of this classification was a realisation on the part of the developed countries that their own welfare was interlinked with the welfare of the developing countries, in which the majority of the poor lived. Quintessentially due to the interdependence between the developed and developing countries, the continued economic growth and prosperity in the developed countries could not be sustained, if the developing countries were allowed to continue to live in poverty (Milbank Memorial Fund, 1948 & Pearson, 1969). Consequently a greater emphasis was placed on the management of poverty by the developed countries, in an attempt to respond to the growing issue of poverty in the Third World. It is these responses which this paper is attempting to evaluate. This paper will purpose to do this by attempting to ascertain the following question, ‘How Is the Increasing Convergence of Poverty Reduction Policies among Global Governance Institutions Manifested?‘ This paper will evaluate this question by analysing the poverty alleviation strategies manifested by the global governance institutions (GBIs) e.g. World Bank, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and further explain how they have converged over time. On the basis of this it will conclude that the current convergence of poverty reduction strategies on the part of the GBIs is quintessentially manifested through the Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs). Having evaluated this the paper will then move on to analysing the question, ‘Does This Convergence Signal Better Prospects for Poverty Reduction?’ With the use of case studies this paper will argue that to a greater extent, this convergence has benefited poverty reduction; however there are arguments which highlight that this is in fact not the case.

Convergence

In order to evaluate the question, ‘How Is the Increasing Convergence of Poverty Reduction Policies among Global Governance Institutions Manifested?’ it is necessary for this paper to illustrate how the current poverty reduction strategy has come about. This paper will attempt to do this by analysing previous poverty reduction strategies, which have influenced the current strategy advocated by the GBIs.

Amartya Sen defines poverty through the, “entitlement approach [which is his attempt of analysing the] acquirement problem (Sen, 1999, p.38).” The former is the entitlement of a person to a set of commodity bundles, while the latter addresses the issue of the ability of a person in establishing command over the entitled commodities. Sen therefore argues that poverty is a reflection of the, “widespread failure of the entitlement on the part of substantial sections of the population (Sen, 1999, p.38).” Though Sen uses this framework in addressing rural famine, his definition of poverty can be used in a much wider context. As a result of this it is feasible to ask the question, ‘Why are substantial sections of the population not getting their entitlement?’

Poverty Reduction Strategy 1

This question was first addressed as early as the 1950s, when the issue of poverty was placed on the development agenda. The poverty reduction strategy which the GBIs took was based on a comparative approach, which contrasted the developed and developing countries. Through this outlook it was found that industrialization was seen to be the only progressive route to modernisation, and that only through material advancement could social, cultural, and political progress be achieved. Furthermore it was concluded that within market economies the poor are defined as, lacking what the rich have in terms of money and material possessions. As a result of these conclusions the GBIs advocated a poverty reduction strategy which expressed itself in an

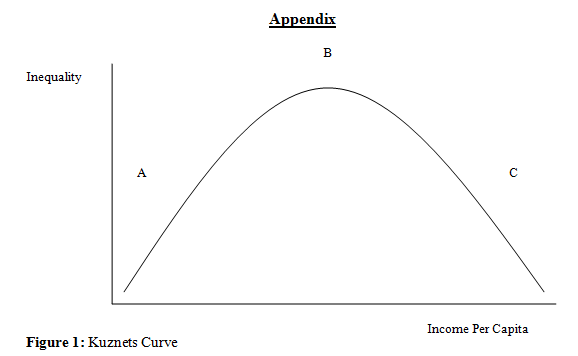

‘industrialisation-first strategy’ which emphasized the role of investment in the development process in order to ensure economic growth in the developing countries. In doing so it was hoped that a ‘take-off into sustained growth’ for the developing economies, would increase income and reduce poverty. Such an economic conception of poverty was to be measured by the annual income per capita (GDP) of a country. The basis of this strategy however was based on certain key assumptions. The first of which was that the capital investments needed to promote the economic growth, would have to come in the form of foreign aid from bilateral and multilateral donors. Secondly that economic growth would reduce income and social inequality in the developing society. Here the assumption is based on the premise that income will ‘trickle down’ to the poorest in society. This can be clearly illustrated by the Kuznets Curve in Figure 1. The curve illustrates that at the early stages of economic growth, the benefits in terms of income will be distributed unequally (A). In essence it will remain locked amongst the minority rich within society. However this will only continue up to a certain point (B). Upon which the income inequality within society will fall, as the incomes of the poor groups would then tend to grow faster than average (C).

Poverty Reduction Strategy 2

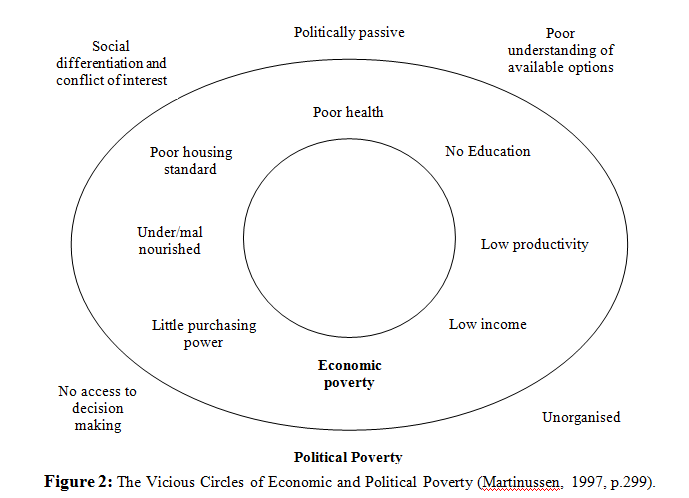

This poverty reduction strategy prevailed until the 1970s, when it was realised by the GBIs that not only was there no reduction in the number of people residing in poverty, but in fact their situation was compounded by the inequality in the distribution of income. As a result there was a definable shift in the manifestation of the poverty reduction strategies, advocated by the GBIs. The GBIs began to study the interaction between, on one hand income and resource distribution, and on the other hand the patterns of economic growth and transformation. Consequently the GBIs began to incorporate poverty assessment in their analysis and poverty alleviation in their development strategies. This is clearly visible in the shift in perception of the poor and consequently the poverty reduction strategy from the 1950/1960s to the 1970s. During the former period the poor were viewed by the GBIs as passive groups within society, who could only be helped through external aid. As a result the development agenda focused more so on economic growth in the developing countries, which they assumed would trickle down to the poor. However in the 70s the perception of the poor changed to be seen as a, “visible category that possessed tremendous potential for helping themselves and societies in which they lived in (Martinussen, 1997, p.297).” Subsequently this shift in perception saw a alteration in poverty reduction strategy on the part of the GBIs, away from macro-economic growth with no emphasis on poor target groups, to macro-economic growth with a greater emphasis on poor target groups. It is crucial to understand that, though the GBIs placed a greater emphasise on poverty reduction strategies, it was very much as an attachment on to the bigger goal of achieving economic growth in the developing countries. This development strategy can be epitomised by the ‘Basic Needs Approach.’ As illustrated earlier, the main argument behind this approach was the idea of redistribution with economic growth. Quintessentially the GBIs sought to continue the promotion of economic growth as their main development strategy, but with measures which diffused capital and other resources more equitably across society. Added to this the GBIs also shifted the categorization of those who are poor, away from just income. They began to embrace all aspects of the poverty complex, as Figure 2 highlights. The diagram exemplifies that the poor in the developing countries are not only defined as having inferior purchasing power, but there are a whole range of other symptoms associated with poverty. Subsequently the GBIs as well as the main bilateral and multilateral aid donors added poverty and the basic needs consideration to their development strategy.

Poverty Reduction Strategy 3

The Basic Needs Strategy prevailed until the 1980s, after which the implications of the international debt crisis and other adverse international economic conditions, shifted the goals of the poverty reduction strategies, once again. This shift was clearly influenced by the emergence of the neo-classical school of thought, in the development discourse. They advocated a need to reduce the states economic role and instead emphasised a stronger reliance on free market forces. Their reasoning behind this policy approach was influenced by their perception of developing country governments being bloated, corrupt, and moreover their intervention in the market encouraged rent seeking activities by institutions, which lead to significant economic inefficiencies (Adleman, 2000). Quite simply they argued that the government intervention in the market e.g. the welfare state was diverting resources which the market would allocate more efficiently. By removing the influence of the state, neo-classics argued that the market would allocate resources and income more efficiently. This liberalisation of domestic markets was epitomised by the World Banks flagship Structural Adjustment Policies (SAPs), which encouraged domestic structural adjustment in the hope of, reducing balance-of-payments and budget deficits, which provided the necessary conditions for economic growth and poverty alleviation. The GBIs made this an important perquisite, before developing countries could resume on the development and poverty alleviation path. More importantly this was a condition to which the developing countries had to show that they were adhering to, in order to receive donor aid.

Poverty Reduction Strategy 4

The 1990 UNDP Human Development Report provided the first challenge to the neo-classical mainstream approach of alleviating poverty. The report advocated a different way in assessing and measuring poverty, which as a result placed a different focus on policy implications. The difference between the neo-classical and human development schools of thought is that the former exclusively focuses on the expansion of only one human choice – income, while the latter embraces the enlargement of all human choices (Martinussen, 1997). In essence it argues that poverty is a multidimensional concept which is not defined by the lack of income but also by ill-health, illiteracy etc (UNDP, 2008). As a result the former advocates a poverty reduction strategy which places a greater emphasis on economic growth to alleviate poverty, while the latter questions this link. The human development school of thought argues that the link between income growth and human welfare, can only be created through public polices that aim to provide service and opportunities equally to all citizens. They argue that this a cannot be left to market mechanisms, which despite allocating resources efficiently does not do so equitably and is therefore an unfriendly policy towards the poor. They instead advocate the continued promotion of economic growth, matched with state lead mechanisms which acknowledge the multidimensional framework of poverty and therefore allocate resources, more equitably across society.

Poverty Reduction Strategy 5

The 1990s also saw the emergence of PRSPs, which can be defined as being the current manifestation of poverty reduction strategies, advocated by GBIs. The PRSPs came about due to a variety of reason ranging from the negative response the SAPs received, to the growing recognition of the importance of the national policy context for aid effectiveness, as the limitations of conventional conditionalities became apparent. Furthermore the PRSP approach taken by the GBIs, are linked to broader development schemes such as the HIPC Initiative and the UN Millennium Goals. Quintessentially they are the required statement of recipient government objectives for the purpose of adjustment and concessional lending, by both the IMF and World Bank. Increasingly bilateral development agencies have taken their lead from this and have reorganised their own country programmes, with reference to national policies set out in the PRSPs. This has also been the case for the UNDP approach to alleviating poverty, which has converged with the mainstream by aligning its human development approach with the PRSPs. Additionally it is possible to illustrate that the components of the PRSPs, are a response to the criticisms levelled against the SAPs of the 80s. The five core principles of the PRSP approach are;

- “Country Driven: promoting national ownership of strategies through broad based participation of civil society,

- Result – Orientated: and focused on outcomes that will benefit the poor,

- Comprehensive: in recognising the multidimensional nature of poverty,

- Partnership – Orientated: involving the coordinated participation of development partners (government, domestic stakeholders and external donors),

- Based on Long-term prospects for poverty reduction (IMF, 2008, p.1).”

The SAPs were criticised for being a, “top-down approach in which programme content was determined by government officials and outside experts without consulting local people on their priorities (Riddell & Robinson, 1995, p.20).” The PRSPs counter this claim by ensuring participation of all levels society, therefore recognising the multidimensional nature of poverty. Furthermore they are country driven; therefore the poverty reduction strategy are nationally owned and conceived. Quintessentially the PRSPs represent the current policy thinking of the GBIs and reflect the changed intentions of the way these organisations do business. Quite simply they reflect the, “change in the way international support to poverty reduction in developing countries is framed and delivered (Booth, 2003, p.132).”

This paper has analysed the various poverty reduction strategies advocated by the GBIs. In doing so it has answered the question ‘How Is the Increasing Convergence of Poverty Reduction Policies among Global Governance Institutions Manifested?’ by illustrating that the current manifestation has come about as a product of the previous poverty reduction strategies.

Good or Bad?

Having illustrated how the poverty reduction strategies of GBIs, have converged into the current PRSP approach, this paper will now move on to analyse the following question, ‘‘Does This Convergence Signal Better Prospects for Poverty Reduction?’ With the use of case studies this paper will argue that to a greater extent, the PRSP approach has had a beneficial impact on the poverty alleviation process. However this paper will also argue that the PRSP approach has had no beneficial impact on the poverty alleviation process.

Beneficial Impact

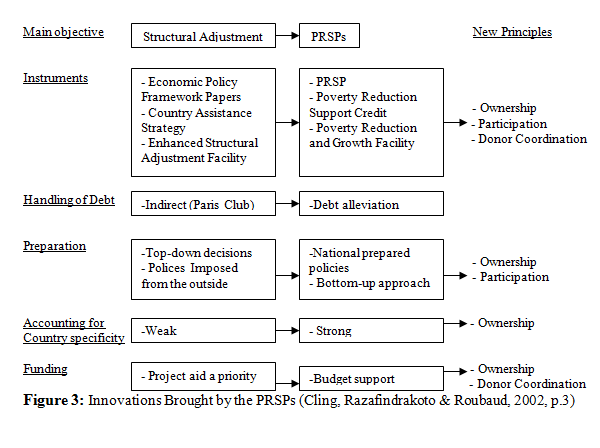

As Figure 3 exemplifies the PRSP initiative has brought into contention a number of new principles. It is these principles by which the PRSP approach, defines itself as being intrinsically different to previous poverty reduction strategies. Consequently it is on the basis of these new innovations -the PRSP process rather than PRSP content – that this paper will assess whether the PRSP initiative, is making a difference (Booth, 2003).

From David Booth’s case study of the PRSP experience for seven countries: Benin, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Rwanda and Tanzania this paper argues that the PRSP approach has made a beneficial difference in the following ways;

- “New spaces for domestic dialogue have been created (Booth, 2003, p.146).”

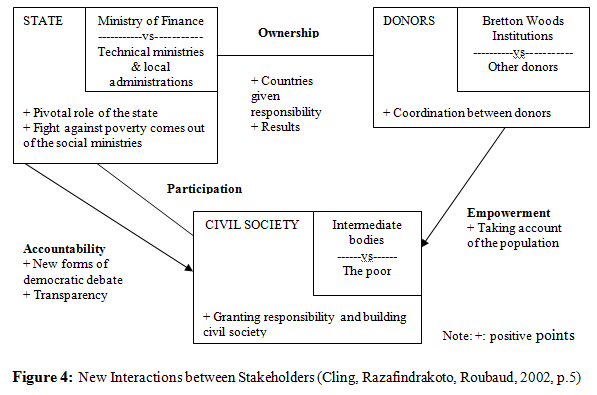

One of the most important contributions made by the PRSPs is its role, in breaking away from the SAP top-down approach and giving back to donor countries, a responsibility for their own development. The PRSPs have ensured this by opening new policy spaces for domestic dialogue, between stakeholders at all levels. By broadening the PRSP approach among national stakeholders, not only has this provided an important source for improved policy ideas, but it has also ended the technocratic approach previously favoured by SAPs. As Figure 4 shows the previous relationship between the state and donors has become more open by, allowing national ownership of the PRSP process. Additionally Figure 4 also importantly illustrates the emergence of a new stakeholder in the PRSP process. The engagement of civil society – mainly through NGOs at the decision making stage – means that grass root organisations who voice the opinion of the poor are, “engaged in policy activities with the clear potential to scale up their contribution to poverty reduction and help challenge non-transparent and unaccountable government behaviour (Driscoll & Evans, 2005, p.8).” In engaging civil society in a more strategic manner, PRSPs ensure greater national ownership of poverty reduction strategies, greater empowerment of the poor by improving the political debate to allow them to influence strategy, which reflects real social needs and greater accountability through participation in the discussion over government policies.

- “PRSPs have mainstreamed and broadened national poverty reduction efforts (Booth, 2003, p.140).

“With varying levels of magnitude from country to country,Booth’s case studies indicate that poverty reduction has moved up the national government agendas. This shift can be illustrated by the fact that the responsibility for co-ordinating and implementing the countries PRSP, was being dealt with by the Ministries of Finance. Additionally this shift towards Finance Ministries having a greater control over PRSPs has lead to further reforms. In accordance with the HIPC and Millennium Goals objectives, governments have increased poverty orientated spending. This has resulted in an increase in the % of GDP being spent in sectors such as, education and health. Moreover PRSPs have been helped by Medium Term Expenditure Frameworks, which have, “created a tighter link between poverty reduction and budget priorities as well as medium-term allocation of national and donor resources (Booth, 2003, p.140).” Finally as a result of the multidimensional definition of poverty embedded within the PRSP approach, there has been a move away from focusing poverty reduction efforts on the social sectors, to endorsing more comprehensive, multi-sectoral policy strategies (Driscoll & Evans, 2005).

- “PRSPs invite more substantial transformation of the aid relationship

(Booth, 2003, p.151).”Previous aid strategies had weakened the capacities of national institutions, by imposing high transaction costs on government. By supporting the principle of national ownership, a continuation of the previous policies would hinder this process. Therefore the PRSPs provided an opportunity for aid donors to reform the aid agenda, in accordance with the current poverty reduction strategy advocated by the GBIs. This can be shown in a variety of ways. For example donors have now moved away from the project orientated approach which is accused of, “cultivating patron-client relationships, encouraging rent seeking orientation in government, and influencing domestic politics towards patron-client models that work against state effectiveness and accountability (Booth, 2003, p.152).” Instead the donors have shifted towards sector programmes and general budget support. This facilitates the speeding up of poverty reduction measures, which helps increase confidence in government systems.

Non-Beneficial Impact

By using case study examples, this paper will now move on to illustrate how the PRSP approach advocated by the GBIs, have not made a beneficial difference. This is exemplified in the following ways;

1. Participation: According to Frances Stewart and Michael Wang,

participation can be broken down to represent two important concepts. They argue that participation can either be interpreted to involve, “empowerment – implying significant control over decision making – or rudimentary levels of consultation, where little delegation of decision making occurs (Stewart & Wang, 2003.p.6).” Both interpretations are important in analysing the PRSP approach, because the former implies a greater sense of national ownership over the development process, while that later is effected by the level of participation by civil society. In essence these considerations propose that the participatory process can be evaluated on both the, “intensity of the participant’s engagement and the degree of inclusion or exclusion of various groups (Stewart & Wang, 2003.p.7).” The World Bank vision of participation suggests an inclusive process, which encompasses a broad section of society as well as a process which allows, greater influence and control over policy-making (World Bank, 2002). From the case studies used by Stewart and Wang, they argue that the participation process has not been all encompassing and that there has been the exclusion of key stakeholders. These have been;

§ Parliamentarians: National parliaments have played a minimal role in

formulating the national PRSP, for example in Kenya “less that 10% of MPs attended consultations, as they viewed the PRSP as a technical planning process not subject to party-political debate (Stewart & Wang, 2003.p.10).”

§ Trade Unions: Though trade unions represent a narrow section of society,

they still represent an important group. It was therefore surprising that they were not consulted as in Mali.

§ Marginalised Groups: Though the purpose of civil society in the PRSP

process was to voice the opinion of the poor in Bolivia, “organisations representing certain groups – peasants and indigenous people – did not attend themselves and were represented by local authorities who were only weakly connected to the poor (Stewart & Wang, 2003.p.11).”

Furthermore the case studies indicate that the participation process was an exclusive process, with only selected groups being given the opportunity by governments to engage in the PRSP process. This shows not only the lack of broad participation as advocated by the PRSP process, but also indicates how politically loaded the poverty reduction process is. For example in Ghana the trade unions were not consulted but the, “government preferred to consult with more sympathetic institutions like the Civil Service Union (Stewart & Wang, 2003.p.11).” This goes to show that the PRSP process is neither impartial not representative of society. This weakness if further compounded by the participation process itself, which is limiting because of;

§ Information Availability: Many stakeholders have had very limited access

to information, which governments use in order to compile the PRSP.

§ Language: Civil society participation has been hindered by the choice of

language used, for example in Cambodia the PRSP was not written in Khmer until the final version.

§ Time Frame: The quality of participation in the PRSP process has been

hindered by the rush to complete the paper, so that the countries debt is locked as in accordance with the HIPC Initiative. As a result not only have civil society organisations not been given sufficient time to carry out comprehensive consultations, but also the frequency at which they participate in the process has been low.

2. The Contents of PRSPs: The SAPs were accused of enforcing a one-size-fits all

poverty reduction policy, but the PRSPs have sought to reform this by empowering countries in formulating their own strategies. A direct consequence of such a policy action would be the wide variation of PRSPs, as they would reflect national needs. In essence the polices advocated in the individual PRSPs would see a divergence away from the standard orthodox packages proposed by the SAPs. It is possible to argue that upon evaluating the case studies, the PRSPs have in fact reflected the international poverty agenda. The move towards a multidimensional approach to poverty which is,

“people-centred and pro-poor (Stewart & Wang, 2003.p.16)” and which identifies poverty as a lack of opportunity, empowerment and security, is in fact what is being reciprocated in the PRSPs. For example in the Vietnamese PRSP a great emphasis was placed on agricultural sector polices, such as environmental protection and increasing agricultural productivity (Vietnam, 2002). While in other PRSPs an emphasis of alleviating poverty in the countryside, was by ensuring employment. However these are polices which not only reflect the broader international poverty agenda, but also a continuation of the one-size-fits all approach of the SAPs. Robert Chambers argues that a continuation of imposing a rigid poverty reduction strategy on the rural poor, will not work. This is because such a policy of alleviating poverty by ensuring employment, does not take into consideration the various survival strategies of the poor (Chambers, 1997.) Furthermore the PRSPs are made on the proposition that economic growth – especially private sector growth – is the most effective way out of poverty. Added to this the PRSPs contain elements of first generation policy reforms designed to promote the role of the market. For example the PRSPs push for trade liberalisation, fiscal and balance-of-payments balances, financial sector reforms, and privatisation. The PRSPs also endorse second generation reforms which adhere to the ‘good governance agenda’ and emphasis the need for institutional reform, transparency, and accountable public administrations. It is therefore feasible to argue that, PRSPs are part of a process which, “advances the international poverty agenda rather than as a sign of national ownership of PRSPs (Stewart & Wang, 2003.p.16).” The question which needs to be asked therefore is, ‘Why is this the case?‘ The reason for this can be found in the donor relationship with aid recipient countries. Under the SAPs the GBIs gave aid to recipient countries on the basis that they met certain conditionalities – changes in economic and social policy. However this process undermined the sovereignty and democracy of the recipient countries. These negative effects of these conditionalities were attempted to be addressed by the PRSPs process, by ensuring greater participation and national ownership. Though the PRSP process attempts to reduce the negative effects of the SAP conditionalities, they are still by definition a new set of conditionalities by which HIPC countries have to adhere to, in order to have their debts locked. Therefore the principle of ownership seems antithetic, as countries still have to meet the conditionalities imposed by donors in order to receive aid. This explains why the PRSPs reflect the international poverty agenda, as they are under the pressure to make sure that they comply with the ideological framework of the GBIs in order to receive aid as the following statement suggests, “there was a strong reported tendency towards self-censorship on the part of the Ghanaian authorities, of writing into the PRSP drafts wording designed to meet the anticipated demands of the IFIs (International Financial Institutions) (Stewart & Wang, 2003.p.19).”

Conclusion

This paper has illustrated that the PRSPs are the current reflection of a, “wider international convergence of public policy around global integration and social inclusion (Craig & Porter, 2002, p.1).” This convergence has come about through a process, of learning from the mistakes of previous poverty reduction strategies and the influence of donor aid ideology. Therefore a clear conclusion which can be made when assessing the convergence of the poverty reduction strategies of the GBIs is that the poverty reduction strategies are not dictated by the need to alleviate global poverty. They are heavily influenced by ideological explanations, as well as the politics of donor aid.

This paper then went on to evaluate whether the PRSPs were making a beneficial or non-beneficial difference. In terms of beneficial impacts the PRSPs have enhanced the poverty reduction process by engaging with civil society and creating national ownership of the development agenda. However in terms of the non-beneficial impacts of the PRSP process, this paper has illustrated a number of ways in which it has not made a difference. The paper has shown that PRSPs have not empowered new sections of society, as the participation process is heavily influenced by who are chosen to be consulted. Furthermore this paper has indicated that that the PRSPs are in fact “Old wine in new bottles (Cling, Razafindrakoto & Roubaud, 2002) as they provide no new poverty reduction strategies, but instead advance the current international poverty agenda.

Bibliography

Adleman.I, (2000) ‘The Role of Government in Economic Development’ in Tarp.F and (eds.), Foreign Aid and Development: Lessons and Directions for the Future, (London, Routledge).

Booth.D, (2003) ‘Introduction and Overview’ Development Policy Review, Vol.21 No.2.

Chambers.R, (1997) Whose Reality Counts? Putting the First Last (London, Intermediate Technology Publications).

Cling. J.P, Razafindrakoto.M & Roubaud.F, (2002) ‘The PRSP Initiative: Old Wines in New Bottles?’ ABCDE-Europe Conference Paper, 24-26 June Oslo.

Craig.D & Porter.D, (2002) ‘Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers: A New Convergence’ World Development Vol.31, No.1.

Driscoll.R & Evans.A, (2005) ‘Second Generation Poverty Reduction Strategies: New Opportunities and Emerging Issues’ Development Policy Review, Vol.23 No.1.

Escobar. A, (1995) Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World (Princeton, Princeton University Press).

International Labour Organisation, (1976) Employment, Growth, and Basic Needs: A One-World Problem (Geneva, International Labour Organisation).

International Monetary Fund, (2008) Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSP) [http://www.inf.org/external/np/exr/facts/prsp.htm]. Accessed 6 March 2008.

Martinussen.J, (1997) Society, State and Market: A Guide to Competing Theories of Development (London, Zed Books).

Milbank Memorial Fund, (1948) International Approaches to Problem of Underdeveloped Countries (New York, Milbank Memorial Fund).

Pearson.L, (1969) Commission on International Development: Partners in Development (London, Pall Mall Press).

Rahnema. R, (1991) ‘Global Poverty: A Pauperizing Myth’ Interculture, Vol.24, No.2.

Riddell.R & Robinson.M, (1995) Non-Governmental Organisations and Rural Poverty Alleviation (Oxford, Clarendon Press).

Sen.A, (1999) ‘Food, Economics, and Entitlements’ in Drèze.J & Sen.A (eds.), The Political Economy of Hunger Volume 1: Entitlement and Well Being (Oxford, Clarendon Press).

Stewart.F & Wang.M, (2003) ‘Do PRSPs Empower Poor Countries and Disempower the World Bank, or is it the other Way Round?’ Queen Elizabeth House Working Paper Series Number 108.

United Nations Development Programme, (2008) Poverty Reduction [http://www.undp.ord/poverty]. Accessed 6 March 2008.

Vietnam, Government of (2002), The Comprehensive Poverty Reduction and Growth Strategy.[http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/TOPICS/EXTPOVERTY/EXTPRS/0,,contentMDK:20200608~menuPK:421515~pagePK:148956~piPK:216618~theSitePK:384201,00.html]. Accessed 21st February 2008.

World Bank, (2002) Source Book for Poverty Reduction Strategies (Washington D.C., World Bank).

—

Written by: Rajpal Singh

Written at: School of African and Oriental Sciences

Written for: Professor Henry Bernstein

Date written: 2008

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Impact of Globalisation on Poverty and Inequality in the Global South

- Global Cybersecurity Governance Is Fragmented – Get over It

- The Role of Global Governance in Curtailing Mexican Cartel Violence

- China’s Take on Changing Global Space Governance: A Moral Realist Argument

- When It Comes to Global Governance, Should NGOs Be Inside or Outside the Tent?

- Eating Last and the Least: Analysing Gender in Global Hunger