“As a country, we have demanded more and more energy. But we have not brought on line the supplies needed to meet that demand….” Vice President Richard Cheney (Cheney 2001)

After land, oil causes more conflicts than any other natural resource, and it is highly likely that actors engaging in conflict over oil will attempt to disguise their motivations. (Alao 2008) In recent years, the United States has been quietly increasing its presence in West Africa with a variety of declared humanitarian interests. (State 2009) Discussion as to the ‘true’ motivations vary, from the need to shore up its role as global hegemon in the face of Chinese advances (Rogers 2007), to attempts to neutralise the territory as a base camp or staging ground for terrorists, to the need for new desire for US goods. (Barnes 2005) The most pragmatic of the ‘true’ motivations offered is the need to secure oil supplies.

In order to promote and maintain long term security, both in the US and in West Africa, an active and representative civil society must be established in the latter. This need not automatically take the form of a Western democracy, but the population must have the opportunity to influence and control, to a degree, the environment in which they live. The relationship between this concept of civil society and the US (oil-motivated) presence, and the impact that this relationship has, shall be set out and dissected.

This paper seeks to explore the relationship between the actions of the US in West Africa and the tensions this can cause between short term and long term gains. The first section will contextualise the importance of oil and outline distribution. The second segment will cover the securitisation of territory as a method of ensuring continued oil supplies, via military training. The third part explores the tangible changes in political and civil society oil discovery brings, such as aid, trade and infrastructure. Finally, the fourth section covers the less tangible changes to West Africa society, such as changes to underlying ideology and political thought.

The countries referred to by ‘West Africa’ comprise of the 16 countries of the United Nation’s definition – Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Togo – plus those on the coast of the Gulf of Guinea that have oil reserves – Sao Tome and Principe, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Congo-Brazzaville.

Oil: Context and Distribution

Oil is the basis of industry and its supply is essential to the maintenance of an industrial or post-industrial economy, and by extension, that nation’s civil and political society. The finite amount of this natural resource increases its value, both in fiscal terms and in its perceived worth. Consequently, nations that discover oil in their territory are guaranteed to garner attention, though not necessarily the rewards such a discovery should rightfully earn. While it would seem that conflict over oil is inevitable, Morse contends that, much as with the many examples of riparian cooperation, the limited supply of oil may act as a catalyst for cooperation. (Morse 2007)

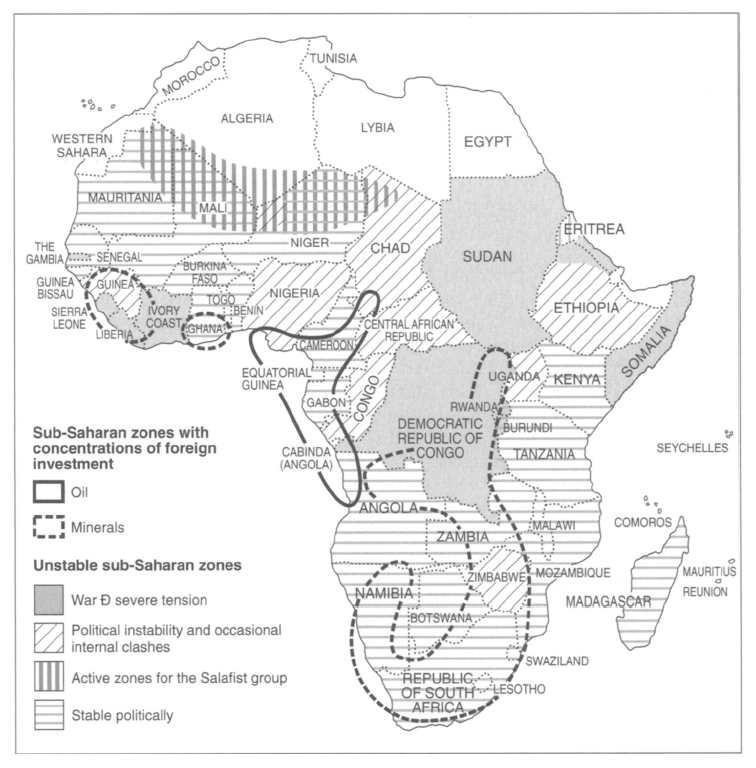

Figure 1 Distribution of oil and minerals (Abramovici 2004) Since this map above was published, “one of the biggest oil finds in Africa in recent times” has been discovered in Ghana. (BBC 2007)

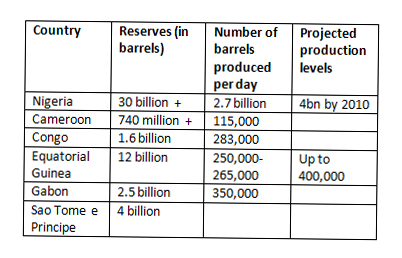

Figure 2 List of countries and respective oil production figures (Ndumbe 2004)

The success of the 1973 embargo by the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) nations indicated to the West that politics and oil, in the Middle East at least, were inextricably linked. The warning against dependence on “foreign powers that do not always have America’s interests at heart” (Cheney 2001) was noted and subsequent developments in the region served to further underline the need for diversification of supply. (Volman 2003) The move toward Africa as a source of oil, “will not only reduce dependence on Middle Eastern oil but will reduce the leverage that Middle Easter oil-producing nations exercise on the global economy.” (Ndumbe 2004) Ndumbe identifies four reasons for the strategic significance of West African oil:

1. The oil off the West African shore can be loaded from offshore and shipped easily without transhipment cost through the Atlantic Ocean to the United States. Offshore exploration also acts as a buffer for any political instability.

2. West African oil is low in sulphur content. Consequently, it provides high gasoline yield, which is the preference of American refineries that are under strict environmental laws.

3. The political risk in West Africa is its underdevelopment and culture of bureaucratic corruption. These factors have greatly contributed to its inability to manage its own affairs. While there is political risk, it is minimal when compared to the Middle East.

4. West Africa is not the subject of combative political culture (radical Islam) and neither is it a ground for competing ideologies such as communism. (Ndumbe 2004)

For these reasons, West Africa presents a prime location for heavy US investment. In the short term, this offers the US the solution to the problem of a growing domestic demand for oil, set against the troublesome backdrop of the political situation in the Middle East. Energy supplies are viewed in the US as being intrinsic to national security (Cheney 2001), so the securing of a reliable and high quality supply at a lower cost is a happy political success.

Yet this benefit must be weighed against the potential long term implications. An oil supply that matches domestic demand will enable a continuation, or even increase, in the rate of fuel consumption. In 2007, the US consumed 20,680,000 barrels of petrol per day, 9,286,000 barrels of which was ‘motor gasoline’. (EIA 2009) In the absence of a drastic change to the supply, and therefore the price of oil there is less pressure on the American public to change its behaviour with regards to energy consumption. This has a twofold effect. Firstly, it underscores the need for political leaders to ensure the continuity of the fuel price status quo if they are to remain in favour with the electorate, as was shown during last year’s Presidential election. Secondly, it adds to climate change, reinforcing the pro-business/anti-environment lobby while seeing the excessive day to day continued use of vehicles. Abramovici recounts that:

According to a former secretary of state for energy, James Schlesinger, at the 15th World Energy Council in September 1992, what the American people learned from the Gulf War was that it was far easier to kick people in the Middle East into line than to make sacrifices to limit US dependence on oil imports. (Abramovici 2004)

The same can be said to be true in Africa. The severity of the threat posed by climate change has been compared to the Cold War (AP 2008) and previous estimates of the scale of potential devastation were evidently far too optimistic. (Science Daily 2009) While the US can enjoy a steady supply of oil at present, the failure of the Bush administration to mitigate pollution has contributed to global warming and to the psychological reluctance of the population to accept the menace we all face. It remains to be seen if Obama will be able to make the much needed progress, but early signs look hopeful. Todd Stern, the Climate Change envoy “pledged to “make up for lost time” in reaching a global agreement on climate change” at the recent UN talks in Bonn. (Maxx 2009)

Physical Security via Military Actions

Since the end of the Cold War, the legacy of US military interaction with Africa was marked notably by Somalia and the Black Hawk down incident, and the complete failure of the Clinton administration to act on the reports of genocide in Rwanda. In both cases, Presidents Bush Sr. and Clinton underestimated their adversary. Bush Sr. allowed United Nations Operation in Somalia (UNOSOM I), to segue from a Chapter VI peacekeeping operation into a Chapter VII mission, (Operation Restore Hope), without a change in the force commitment. (Day 1997) Due to this oversight failure, Task Force Ranger failed and the images of dead marines being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu were beamed around the world. Maj. Clifford E. Day observed that “the US political and military leadership was not willing to commit the warpower necessary to carry out the difficult tasks they were assigned.” (Day 1997)

The Rwandan genocide was characterised from very early on by an unwillingness to get involved on the part of the Clinton White House. On numerous occasions, plans that would have had a significant impact on the ground were presented to the President and his advisors, only to be turned down based on cost and practicality. (Power 2001) Momentarily setting aside the potential number of lives saved, Dallaire points out that if the US had been involved in the initial peacekeeping mission, UNAMIR I, it would have cost “no more than $30 million”, and the subsequent UNAMIR II “would have been only slightly more.” (Dallaire 2003) However, the Clinton White House chose to engage after the killings had peaked, and by “deciding to support the refugee camps in Goma, the US paid ten times that amount – $300 million – over the following two years.” (Dallaire 2003) These experiences have produced the defining theme in the narrative of US intervention in Africa.

The military involvement that followed has, at times, seemed a lot more tentative than operations and engagements in other theatres. Yet despite this, in order to guarantee the supply of oil, the US “is quietly establishing military training and equipment links with a number of countries to secure future supply lines.” (Abramovici 2004)

Military Training

In the aftermath of the genocide, the African Crisis Response Force (ACRF) was launched. A forerunner to the African Crisis Response Initiative (ACRI), “the initiative did not gain traction, as it was viewed by some African leaders, most notably former President Nelson Mandela, as a knee-jerk reaction by the Clinton administration after its failure to intervene in Rwanda and an excuse to establish a foothold on the continent.” (Bah and Aning 2008) Having to contend with this type of perception and mistrust, often of merit in its origins and accuracy, is to be expected of a superpower. Just as in business, the reputation of a nation accords the amount of social capital it can spend.

This was succeeded by the ACRI, a programme “designed to develop basic military capabilities, strengthen combat formations and boost headquarters organisation.” (Abramovici 2004) Benefactors included Uganda, Ethiopia and Senegal. (Bah and Aning 2008) However, “from the start, it was apparent that ACRI, having been crafted around cold war peacekeeping doctrine designed for interstate conflicts, was inappropriate for intrastate conflicts, characterized by total disregard for international humanitarian law and numerous ‘spoilers’.” (Bah and Aning 2008) Berman commented that “‘ACRI had more to do with what the U.S. felt it could provide than what African countries necessarily needed’, since the countries themselves were not consulted about the contents of the programme.” (Bah and Aning 2008)

ACRI was in turn followed by the African Contingency Operations Training Assistance (ACOTA) programme, initiated in 2004 by the Bush administration. The programme “will train and equip new battalions and specialty units in partner countries,” (Volman 2006) differing from “its predecessor by providing training for offensive military operations and weaponry, such as machine guns and mortars.” (Carmody 2005)

The following year, the White House launched the Global Peace Operations Initiative (GPOI). Set up to address “major gaps in international peace operations support”, (State 2004) the aim of this programme was to

…train at least 75,000 personnel globally (with a strong focus on Africa in the initial stages), and to enhance the ability of countries and regional and subregional organizations to train for, plan, manage, conduct, and learn from previous peace operations – by providing technical assistance, training and materiel support to enhance institutional knowledge at headquarters. (Bah and Aning 2008)

The term ACOTA is now used to refer to GPOI’s training program in Africa. (Serafino 2009) The creation of the GPOI was motivated in part to alleviate the strain of peacekeeping missions on Western nations and to shore up the “supply base to meet the growing demand for peace operations personnel.” (Bah and Aning 2008)

There are multiple other programmes, such as International Military Education and Training programme (IMET) “Foreign Military Sales, the Professional Military Exchange (PME) program and Unit Exchange,” which together comprise “the U.S. Security Assistance Training Program (SATP).” (FAS 2004)

IMET grants enable foreign military personnel from countries that are financially incapable of paying for training under the Foreign Assistance Act to take courses from the 2000 offered annually at approximately 150 U.S. military schools across the country, receive observer or on-the-job training, and/or receive orientation tours. (FAS 2004)

African countries that are expected to participate in IMET in FY 2007:

This military training displays an overall shift towards a securitisation of African territory that has been ongoing since the early 1990s. The training of troops in itself is not a bad thing. An active civil society is not possible without a secure place in which interaction can occur (Ignatieff 1993) and securing that space is difficult without the presence of a group of individuals trained to do so. Reciprocally, a political arena in which individuals or groups can express their views and concerns without fear of irrational repression or retribution is much less likely to lead to civil unrest and violence. (Jackson 1982) Despite this, there remains a risk that governments will use their US-trained troops to exact their political agenda.

Africom

The impending creation of a new Combatant Command for Africa – Africom – was announced in February 2007. Supporters contend that this is a step that “accurately reflects Africa’s growing strategic importance and an enlightened US Foreign policy focussed on supporting ‘African solutions to African problems.'” (Berschinski 2007) Opponents “allege that the command demonstrates a self-serving American policy focused on fighting terrorism, security Africa’s burgeoning energy stocks, and countering Chinese influence.” (Berschinski 2007) Africom’s Commander, General William E. Ward outlines the aims of the organisation –

1. We are building the team. We have the opportunity, vision, and determination to redefine how the U.S. military cooperates with and complements the efforts of its U.S., international, and non governmental partners in Africa.

2. AFRICOM will add value and do no harm to the collective and substantial on going efforts on the Continent.

3. AFRICOM seeks to build partnerships to enable the work of Africans in providing for their own security. Our intent is to build mutual trust, respect, and Confidence with our partners on the Continent and our international friends. (Ward 21)

Whether the motivations behind Africom are as benign as General Ward would have us believe is not the topic of our debate. More of interest is that fact that Africom was created, centralising the command structure for a continent that is of new found significance to Washington, and making it easier for flows of information, money, materiel and personnel between the US and Africa to occur. As a long term strategic move, this has gone quite some way to locking in place the bonds between the two continents, a move that will only serve to reinforce future security. By creating a symmetrical dependency – Africa’s reliance on the US for help with military – the US has gone some way to balance the vulnerability its oil addiction has created.

US Influence

The US uses its considerable influence to the advantage of its citizens, much as any nation would. Nations hosting US private military companies are required under the American Service Members Protection Act (ASPA) of 2002 to sign a waiver “exempting US nationals on their soil from prosecution by the ICC” with regards to Article 98 of the Rome Statute. (Bah and Aning 2008) The unquestioned prioritisation of US nationals and interests over a long-term security strategy is reflected suspension of military aid to South Africa, Kenya, Benin, Namibia, Mali, Lesotho, Niger, and the Central African Republic, “depriving them of military assistance to support their peace operations on the continent.” (Bah and Aning 2008)

Countries such as Sao Tome and Principe that have hitherto escaped intense international interest have been thrust into the limelight by oil discoveries (CIA 2009) and are subject to the securitisation that follows. (Ndumbe 2004) However, said process of securitisation is not one sided:

In Sao Tome, a high-ranking government official, who preferred anonymity, told IPS: “Our President Fradique de Menezes actually approached the Americans for some sort of military help, in the event that oil exploration and drilling commences”. He acknowledges his country’s vulnerability given its proximity to Nigeria. The Nigerians have offered to sign a mutual defence pact with their tiny neighbour, which would involve the deployment of Nigerian troops on the islands. “We are a bit worried about this plan and would rather not have Nigerian troops here,” says Alberto, a civil servant in Sao Tome. (Fofana 2003)

There is a normative tendency when discussing such matters to assume that when a superpower becomes heavily involved in the workings of another country, whether that is through trade or military presence, this is negative. This is not to suggest that the US is acting altruistically, but that when making a judgement one should momentarily set aside the idea that the host nation is a victim who receives no benefits. The US, while far from perfect with regards to treatment of other and occupied nations, has a much better reputation than the alternative ‘colonisers’, such as China and Russia.

Attacks Against Infrastructure

While piracy off the Horn of Africa is capturing the world’s attention due to a series of high profile attacks and a concerted effort by a coalition of navies to secure the seas, piracy in the Gulf of Guinea is far worse. (Economist 2009) The USS Nashville is currently completing a tour of the Gulf, teaching local navies how best to contend with the threat:

Seaborne attacks on its facilities since 2006 have progressively cut Nigerian oil exports from 2.2m barrels a day to 1.6m or so today. Last year, in the most notable attack, militants in speedboats raided Royal Dutch Shell’s main offshore facility, in deep seas off Nigeria, blocking off 220,000 b/d in a single raid. Experts on the Nashville have been training Nigerians in hand-to-hand combat and oil-platform protection, among other things. (Economist 2009)

Defending the high seas from piracy is nothing new for the US, but the increasingly dependent relationship between the US economy and that particular oil supply route heightens the stakes for those involved.

Within Nigeria, attacks against oil related infrastructure are fairly common. The neglect of the people of the Niger Delta by the government resulted in the creation of the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP). Its leader, Ken Saro-Wiwa , was executed in 1995 alongside eight others for his part in the opposition to Shell’s work in the Delta. MOSOP’s successor, the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND), which has attracted significant attention since it claimed responsibility for the kidnap of four foreign oil workers in January 2006. (CFR 2009) Mend is an umbrella organisation that covers many disaffected groups who feel they have suffered disproportionately and have seen very few benefits from the hugely disruptive oil extraction that is occurring within their communities. (CFR 2009) The process of extracting oil is messy and has a devastating impact on the locale:

Oil spills, either from pipelines (which often cut directly through villages) or from blowouts at wellheads, are a major cause of pollution and ill health. There have been over 6,000 oil spills totalling over 4 million barrels between 1976 and 1996. Many pipeline leakages might have been avoided if the pipelines were buried below ground as in other countries and if ageing or damaged sections were repaired. Ageing and poorly maintained infrastructure also contributes to pipeline fires and explosions, which claim hundreds of lives annually. In 2006, over 400 people died in two pipeline explosions in Lagos, where leaking pipelines were left unremedied and crowds of impoverished residents desperately scooped up buckets of fuel, to sell or for personal use. (Hesperian 2008)

On top of this, the few rewards that the people of the Niger Delta have been promised go missing – “in 2003, some 70 percent of oil revenues was stolen or wasted, according to an estimate by the head of Nigeria’s anticorruption agency.” (CFR 2009) MEND has staged many terroristic attacks with the aim of disrupting the oil supply to the extent that the government and multinationals are forced to recognise the legitimacy of their claims. It has been successful in its disruption, as “the explosions out in the swamps which have closed down significant parts of the oil industry were carefully placed by people who understood the geography of the pipeline network.” (BBC 2006)

Impact on Civil Society

The discovery of oil has a huge impact on the nation and community. The immense amount of revenue can greatly exacerbate pre-existing issues. As was the case in Nigeria with Biafra, and in Sudan with Darfur, oil rich regions may attempt to secede. The previously mentioned revenue influx has the potential to greatly undermine pre-existing stable forms of government. There was recently great concern expressed in some quarters regarding the potential for violence in Ghana as the discovery of oil reserves that will garner roughly $3m a year in revenue from 2010 onwards raised the stakes in the election – “Never will there have been a better time to be in government in Ghana.” (Economist 2008)

If a country has a corrupt system of governance in place, that corruption will be reinforced and enhanced when multinational corporations arrive to do business. In this way corruption becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. “At the present, many West African economies are fuelled by petrodollars. However, these economies are plagued by corruption and public mismanagement retarding developmentin the region.” (Ndumbe 2004) The need to secure profits for shareholders means companies need to achieve results – if those results are only possibly through the thorough dissemination of bribes, then this is what will happen. (Alao 2007) Given the size of the revenue that these companies control, it is logical to conclude that they hold great sway over the government of a nation. This leads to influence over the political agenda, whether overtly sought or not. It also has the effect of undermining democracy as the government is not dependent on the population for revenue generation and thus is only answerable to them at election time. This is a hugely significant repercussion of the oil industry that the US must address if it wants to ensure future security.

The compensation offered to people on the discovery of oil, as is the case in the Niger Delta, can cause local tensions with regards to distribution. (Alao 2008) The community also suffers as the extraction of oil requires workers with tacit knowledge and skills, which leads to a considerable flood of foreigners into the area. This has other negative side effects as the “influx of comparatively rich, and almost all male workers from the well paid oil industries, has also increased prostitution in previously isolated and stable communities.” (Ohia 1999) The increase in the cases of prostitution, rape and sexual exploitation of females in the vicinity of oil discoveries is well documented (Hesperian 2008), but often receives only a cursory mention in debates on the topic.

Traditional gender roles and a lack of formal employment opportunities contribute to sex work serving as a survival strategy for women living near oil compounds and installations where many male field-based oil workers reside. (Bah and Aning 2008)

Whereas the implications of corruption on long term security and development are quite self-evident (Waal 2004), the subjugation of women in this fashion is overlooked. Studies have shown that when women are given a more equal role within the family unit and the community, there are widespread benefits. (IFAD 2008) The impact women have on strategic narratives is also worthy of consideration.

Another side effect of the arrival of foreigners is the flurry of activity as infrastructure is inserted into the locale, in order to make the prospect of working there attractive. (Alao 2008) This often serves to further highlight the chasm between the rich and the poor and the failures of government to remedy this.

Ideological

The decades that followed the end of the colonial era were, in many West African countries, marked by considerable turmoil. Coups, military rule and civil war pock the recent history 15 of the 21 countries covered in this paper (CIA 2009). The debate over the degree to which the colonial experience created a culture of corruption and weak governance, and whether this is manifesting itself in the presence as neo-colonialism, continues to rage. (Millar 2006)

It is in the long term interests of the US if African society is representative and allows the individual a degree of autonomy. This will have the effect of integrating nations into the international order, thereby limiting the chances of their being recruited by hostile forces and subsequently becoming involved in terrorism. The West has no authority with which to impose adherence to human rights (Ignatieff 2000), yet the psychological impact of exposure to the US will hopefully encourage a shift in public discourse in this direction. History has shown that leading through example – especially with regards to fundamental reform of society and the political and public discourse – and allowing other actors to make their own choices is far less traumatic for the society than the imposition of outside views. (Xiong 1990) While it is not difficult to see that commitment to human rights issues is trumped by national interests, such as security or trade, there is a strong likelihood that even a temporary or rhetorical commitment to them will have an impact on the environment in which contact occurs.

Conclusion

Given the changing nature of threats faced and the increased interconnectedness of the world, any serious attempt to create long term security in the US must address the potential causes of grievances abroad. Given the various issues that arise from the oil industry that were detailed above, while the interest of the US in increasing the securitisation of West Africa is logical, it should not become too deeply entrenched in foreign policy ideology. If this were to occur, then the US would be running the risk of ossification, a risk that invariably ends with the missing of warning signs that the security situation is about to break.

It is imperative that American oil companies involved in exploration and production activities assist these countries in developing strategies that would compel and encourage meaningful use of oil revenue toward regional growth and the building of sustainable political and economic institutions that would benefit all. (Ndumbe 2004)

Bibliography

Abramovici, Pierre. “United States: The New Scramble for Africa.” Review of African Political Econonmy, 2004: 685-690.

Alao, Abiodun. Natural Resources and Conflict in Africa: The Tragedy of Endowment. London: University of Rochester Press, 2007.

-. “Oil and Conflict Lecture.” King’s College, London, 27 October 2008.

AP. UK diplomat compares climate change to Cold War. 3 September 2008. http://www.iht.com/articles/ap/2008/09/03/europe/EU-Britain-Military-Climate-Change.php (accessed March 20, 2009).

Bah, A. Sarjoh, and Kwesi Aning. “US Peace Operations Policy in Africa: From ACRI to AFRICOM.” International Peacekeeping (International Peacekeeping), 2008: 118-132.

Barnes, Sandra T. “Global Flows: Terror, Oil, and Strategic Philanthropy.” African Studies Review, 2005: 1-23.

BBC. Nigeria’s shadowy oil rebels. 20 April 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/4732210.stm (accessed April 28, 2009).

-. UK’s Tullow uncovers oil in Ghana. 18 June 2007. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/6764549.stm (accessed April 29, 2009).

Berschinski, Robert G. Africom’s Dilemma: The ‘Global War on Terrorism,’ ‘Capacity Building,’ Humanitarianism and the Future of US Security Policy in Africa. Strategic Studies Institute, 2007.

Carmody, Pádraig Risteard. “Transforming Globalization and Security: Africa and America Post-9/11.” Africa Today, 2005: 97-120.

CFR, Council on Foreign Relations. MEND: The Niger Delta’s Umbrella Militant Group. 2009. http://www.cfr.org/publication/12920/ (accessed April 28, 2009).

CIA. CIA Factbook. 23 April 2009. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/tp.html (accessed April 28, 2009).

Dallaire, Romeo. Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda. London: Arrow Books, 2003.

Day, Maj. Clifford E. “Critical Analysis on the Defeat of Task Force Ranger.” Air Command and Staff College, 1997.

Economist, The. Ghana’s Elections, Hold your breath. 27 November 2008. http://www.economist.com/world/mideast-africa/displaystory.cfm?story_id=12684889 (accessed April 29, 2009).

-. Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea: A clear and present danger. 16 April 2009. http://www.economist.com/world/mideast-africa/displaystory.cfm?story_id=13496711 (accessed April 29, 2009).

FAS, Federation of American Scientists. International Military Education and Training (IMET). 2004. http://www.fas.org/asmp/campaigns/training/IMET2.html (accessed April 29, 2009).

Fofana, Lansana. Sao Tome and Principe: Oil raises hope and fear. 30 June 2003. http://www.afrika.no/Detailed/3767.html (accessed April 29, 2009).

Group, National Energy Policy Development. National Energy Policy, Reliable, Affordable, and Environmentally Sound Energy for America’s Future. Washington DC: National Energy Policy Development Group, 2001.

IFAD. Women and microfinance. 2008. http://www.ifad.org/events/yom/women.htm (accessed April 28, 2009).

Ignatieff, Michael. Blood and belonging: Journeys into the new nationalism. London: Viking, 1993.

-. The Rights Revolution. Toronto: Anansi, 2000.

Jackson, James L. Wood and Maurice. Social Movements – Development, Participation and Dynamics. London: Wadsworth, 1982.

Maxx, Arthur. Obama’s Climate Change Team Debuts At UN Talks. 29 March 2009. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2009/03/29/obamas-climate-change-tea_n_180441.html (accessed April 29, 2009).

Millar, Simon R. “African Governance Modalities Hindering Development.” 2006.

Morse, Captain J. “Share Oil Resources or Suffer the Consequences: Will Nations Co-operate or is Violent Competition for Oil Inevitable? .” Seaford House Papers, 2007: 39-56.

Ndumbe, J. Anyu. “West African Oil, US Foreign Policy and Africa’s Development Strategies.” Mediterranean Quaterly, 2004: 93- 104.

Ohia, Donny. Multinational Companies and Human Rights in Nigeria. June 1999. http://www.humanrights.de/doc_en/countries/nigeria/multinationals.html (accessed April 29, 2009).

People’s Health Movement, Medact, and Global Equity Gauge Alliance. “Oil extraction and health in the Niger Delta.” In Global Health Watch 2: An Alternative World Health Report. Zed Books, 2008.

Power, Samantha. “Bystanders to Genocide.” The Atlantic. September 2001. http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/200109/power-genocide (accessed April 28, 2009).

Rogers, Paul. The United States and Africa: eyes on the prize. 15 March 2007. http://www.opendemocracy.net/conflict/us_africa_4438.jsp (accessed April 28, 2009).

Science Daily. Climate Change Likely To Be More Devastating Than Experts Predicted, Warns Top IPCC Scientist. 15 February 2009. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/02/090214162648.htm (accessed March 20, 2009).

Serafino, Nina M. The Global Peace Operations Initiative: Background and Issues for Congress. Washington DC: Congress Research Service, 2009.

State, Department of. Bureau of African Affairs. 7 April 2009. http://www.state.gov/p/af/ (accessed April 28, 2009).

-. GLOBAL PEACE OPERATIONS INITIATIVE (GPOI). October 2004. http://www.state.gov/t/pm/ppa/gpoi/index.htm (accessed April 28, 2009).

Volman, Daniel. “The Bush Administration & African Oil: The Security Implications of US Energy Policy.” Review of African Political Economy, 2003: 573-584.

-. US Military Programmes in Sub-Saharan Africa, 2001-2003. 1 March 2006. http://www.concernedafricascholars.org/military/military06.html (accessed April 28, 2009).

Waal, Alex de. “Rethinking aid: Developing a human security package for Africa.” New Economy, 2004: 158-163.

Waal, Alex de. “Rethinking Aid: Developing a Human Security Package for Africa.” New Economy, 2004: 158-163.

Ward, General William Kip. Africom Dialogue. 2007 December 21. http://www.africom.mil/africomDialogue.asp?entry=20 (accessed April 28, 2009).

Xiong, Mark P. Petracca and Mong. “The Concept of Chinese Neo-Authoritarianism: An Exploration and Democratic Critique.” Asian Survey, 1990: 1099-1117.

—

Written by: Bethany Torvell

Written at: King’s College, University of London

Written for: Dr Petra Dolata-Kreutzkamp

Date written: 2009

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- To What Extent Has China’s Security Policy Evolved in Sub-saharan Africa?

- Are Non-democracies More Susceptible to Coups than Democracies in West Africa?

- Female Genital Cutting in Africa: The West and the Politics of ‘Empowerment’

- French Intervention in West Africa: Interests and Strategies (2013–2020)

- A New Era of UN Peacekeeping? The Women, Peace and Security Agenda in Africa

- Nuclear Proliferation and Humanitarian Security Regimes in the US & Norway