To find out more about E-IR essay awards, click here.

Globalization has brought the international financial community to unprecedented levels of integration and efficiency. This relatively new global marketplace has increased world prosperity but at the same time presents new problems that necessitate the resurgence and refinement of financial regulation. The first goal of such regulation is to identify areas of systemic risk within the global financial system so the policies can be targeted to mitigate the spread of financial crises while creating minimal impediments to market efficiency. Firstly, understanding the underlying principles behind the Asian financial crisis of the 1990s and the current global recession provides us with critical information for the analysis of how globalization is impacting international financial markets. From this, we are able to highlight areas of weakness in the global financial system and factors that compound crises by understanding the foundational elements that contributed to these financial meltdowns. In almost all crises there is a “bubble” or an inflated idea of market value based on informational asymmetry. These unsustainable bubbles eventually collapse sending financial tremors throughout the system that are perpetuated by systemic risks. There are three ecumenical risks that transform small-scale problems into a global crisis: capital market liberalization and the associated unrestricted flow of capital, emerging financial markets that provide regulatory loopholes, and lastly, but most importantly, the lack of a minimum level of transparency within global finance. Although all three aspects are imperative to international stability, the last is by far the most salient. Capital market liberalization and emerging financial markets are areas of weakness but are inherent components of a developing financial system. As such, transparency should be paramount in all policy directives regarding this issue. In addressing these issues a greater level of stability can be achieved and maintained within the international financial system.

This paper will concentrate on the first step to increasing stability; which is identifying important areas of weakness within global financial regulation and not the subsequent enforcement of such policies. For the purpose of this historical analysis, there will also be a focus on the policy decisions and actions of key players because these elements are relatively malleable and can be changed to mitigate the risk of future financial issues. Conversely, there’ll be little time given to the underlying numerical macroeconomic theory because it is more or less a constant and the scope and length of this paper do not permit such meticulous mathematical analysis.

In both the Asian and contemporary financial crises there are commonalities in the causation and dissemination of financial turmoil. In both situations, markets were inflated by a prolonged period of economic growth that created inflated expectations for the market that were not sustainable and ultimately were not realized. Speculative “bubbles” are formed and after their inevitable collapse, problems are amplified by three systemic risks in the global financial system. As mentioned above, these include capital market liberalization, emerging financial markets, and a pronounced lack of global transparency. These factors are prevalent in the global financial system but require a spark in the form of inflated ideas of market value and future performance. Bubbles create an issue because, “it is not necessarily easy to spot a bubble in advance, no matter how clear it seems in retrospect.[1] The problem of early identification arises because very few areas of strong economic growth are overly inflated and, “[s]ome things which may appear to be bubbles are not, but rather reflect true long-term changes in the economy.[2] The difficult task for governing bodies, both domestic and international, is to uncover the underlying erroneous assumptions that lead to magnified ideas of market value. While individual financial crises may have their specific initial causes; it is still these three market-wide issues that are the underlying factors perpetuating economic problems in the global markets.

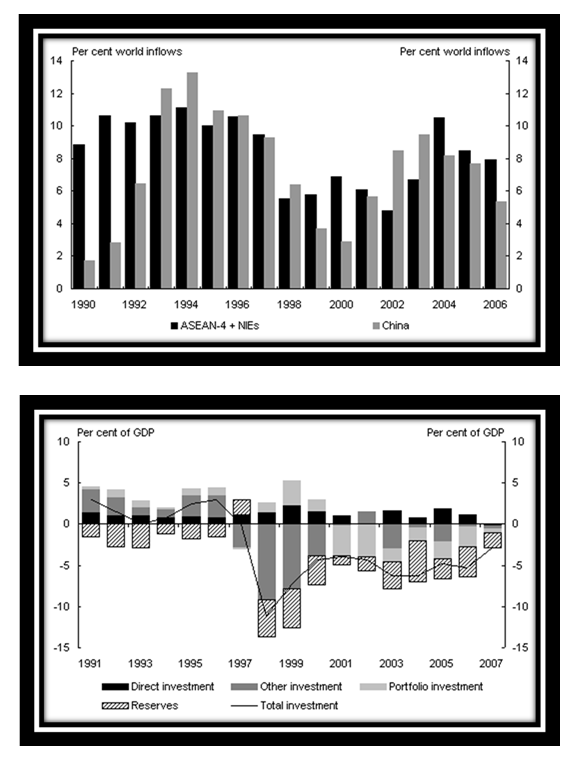

Throughout the 1990s Asian markets were bolstered by a strong world economy and high levels of foreign direct investments, as seen in Figure 1[3] of the appendix. The financial crisis erupted mid-1997 when the Thai government decided to introduce a floating exchange rate and transition away from an exchange pegged to the US dollar.[4] Given the high levels of debt within the country and limited capital controls, the currency collapsed.[5] This massive devaluation created concern for investors in Asian countries with similar macroeconomic policies. The bubble in this case was a seriously overvalued baht that had very little capital backing and economic growth that was perpetuated by foreign direct investment. Increased transparency and accurate reporting from countries involved in the crisis could have reduced the speculative bubble by providing realistic information on growth and macroeconomic fundamentals within the region. This would inevitably have reduced investment in the region but concurrently would have reduced the economic pain after the bubble burst. Unfortunately this was not the case; the idea spread that the economic viability of countries with pegged exchange rates was vastly lower than expected and this lack of confidence spread throughout Asia. “Except for Ecuador in 1998–99 and Brazil at present, every emerging market country that suffered a capital account crisis in the last decade had some form of pegged exchange rate in place before the crisis.”[6] Figure 2[7] in the appendix graphically demonstrates the severe drop in exchange rates and equity prices experienced by Thailand, Malaysia, Philippines, Indonesia, Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore. Liberalized Asian financial markets had little control over the massive financial outflows from the region that ultimately transformed a single currency collapse into a regional crisis. The same trend – artificially high speculative value – is the underlying cause for the subprime mortgage crisis and subsequently the global recession.

Despite the geographical differentiation, the current crisis shares many of the same issues. The crisis started in 2007 when the overpriced US housing market began to decline; but it was not just this factor that brought the US economy to its knees. There was a combination of many factors that created the financial meltdown. This perfect storm led to what is arguably the largest bubble in history, which was founded in US policy, but spread throughout the international financial system through inherent systemic risks. The infamous investor George Soros pointed out that, “the housing bubble was merely the trigger that detonated a much larger bubble. That super-bubble, created by the ever-increasing use of credit and debt leverage, combined with the conviction that markets are self-correcting, took more than 25 years to grow [and] now it is exploding.”[8] The complete list of causes for this market collapse found in Figure 3[9] in the appendix is quite expansive and highlights a number of causes that culminated in this catastrophe. For the purpose of this paper, there will be a focus on the top four causes according to the Congressional Research Service: imprudent mortgage lending, the housing bubble, global imbalances, and securitization. It is important to understand the triggers of the global financial crisis in order to discern how globalization and systemic risk disseminate destabilization.

Imprudent Mortgage Lending: Against a backdrop of abundant credit, low interest rates, and rising house prices, lending standards were relaxed to the point that many people were able to buy houses they couldn’t afford. When prices began to fall and loans started going bad, there was a severe shock to the financial system.[10]

Globalization has played a key role in the facilitation of the abundant credit that fuelled the subprime mortgage crisis. Credit and mortgage debt, “provided an illusory way for the economy to generate growth.”[11] Once this massive over-leveraging unravelled, many countries, particularly China, found themselves “relending the dollars they earn back to the United States in order to maintain the US market for their exports.”[12] This global symbiotic relationship has allowed the US to continue to consume at an unsustainable level and at the same time has saturated the Chinese economy with US dollars and US dollar-backed securities. The relationship between these two hegemonies has been exacerbated by the global recession because the debt burden of the enormous US stimulus package makes the US government and consumers increasingly prone to purchasing through debt backed by foreign countries.

Housing Bubble: With its easy money policies, the Federal Reserve allowed housing prices to rise to unsustainable levels. The crisis was triggered by the bubble bursting, as it was bound to do.[13]

The housing bubble is also a domestic issue that was perpetuated by globalization and the downward pressures placed on US interest rates because of global financial integration. Domestic monetary policy “encouraged financial institutions to expand credit aggressively by reducing their short-term funding costs” while in tandem, “stable inflationary expectations and the exchange rate policies in the People’s Republic of China and other Asian economies restrained long-term U.S. interest rates.”[14] The undervaluation of the Chinese Yuan kept inflation in the US low which in turn created an artificially low domestic nominal interest rate. The easy money created by these low long-term interest rates produced increased demand in an already strong housing market, causing prices to climb drastically.[15]

Global Imbalances: Global financial flows have been characterized in recent years by an unsustainable pattern: some countries (China, Japan, and Germany) run large surpluses every year, while others (like the U.S and U.K.) run deficits. The U.S. external deficits have been mirrored by internal deficits in the household and government sectors. U.S. borrowing cannot continue indefinitely; the resulting stress underlies current financial disruptions.[16]

There is a pronounced cultural difference between East and West with regards to consumption. The current trade deficits in the United States are a symptom of rampant consumerism and debt financing. Unlike the last two causes that were “accidental”, the imbalance in global financial flows has been a defining feature of the contemporary global market. It is basic economics that a country biased towards present consumption on the intertemporal production possibilities frontier must at some point sacrifice future consumption. In 2004, “America’s consumer debt…topped $2 trillion for the first time”, and well before the financial crisis there were concerns about high consumer debt that, “represents the kind of “bubble” that the stock market grew into during the 1990s.”[17]

Securitization: Securitization fostered the “originate-to-distribute” model, which reduced lenders’ incentives to be prudent, especially in the face of vast investor demand for subprime loans packaged as AAA bonds. Ownership of mortgage-backed securities was widely dispersed, causing repercussions throughout the global system when subprime loans went bad in 2007.[18]

Securitization played a key role in spreading the fallout from the financial crisis, as well as facilitating its creation. It is defined as “a form of financing which involves the pooling and true sale of financial assets and issuance of securities that are repaid from the cash flows generated by such assets.”[19] Prior to the financial crisis, the US government mandated the provision of subprime mortgages to low-income buyers through legislation such as the Community Reinvestment Act.[20] These policies created a large number of high-risk investments that were then securitized and incorrectly packaged as AAA securities. The risk was further spread through derivative products such as credit default swaps (CDS) and these toxic assets permeated the global financial system. It was a combination of the infancy of these financial products in combination with their exponential growth in world markets that led to this large-scale downturn. To put this in perspective, “The first CDS contract was introduced by JP Morgan in 1997 and by mid-2007, the value of the market had ballooned to an estimated $45 trillion, according to the International Swaps and Derivatives Association – over twice the size of the U.S. stock market.[21] When the mortgages underlying the securities went into default, financial institutions came to the realization that the “highly secure” assets they acquired were now worth very little. The implosion of this bubble started a domino effect that led to the largest financial crisis since the Great Depression.

The securitization and the creation of complex financial products have led to an age where governance of the financial sector, both domestic and international, seems almost insurmountable. Globalization has created extraordinary levels of financial integration and, given this, domestic financial dangers are now compounded by the decisions of global players. The main causes of the current financial crisis have either been compounded or created by globalization. Imprudent mortgage lending and the housing bubble were created by artificially low interest rates fuelled by low foreign commodity prices. The liberalization of global capital markets has spread the problems of the US economy throughout the world while allowing US government and citizens to consume at unsustainable levels. Furthermore, the securitization of financial products has allowed unparalleled levels of debt leveraging and created a financial bubble based on vastly overvalued mortgage-backed securities.

Through the analysis of the Asian and current financial crisis, one can come to see the imparity of global financial regulation. While these two main events provide ample justification for increased regulation, it is the systemic risk within the global economy that increasingly necessitates an overhaul of the international financial governing bodies. The scrutiny of these crises allows us to identify financial sparks that in themselves are not overtly dangerous. It is when these sparks are combined with fuel in the form of systemic risk that a large-scale explosion can occur. The identified risks of capital market liberalization, emerging financial markets such as China, and a lack of transparency provide ample fuel for minor sparks in the global system to create a financial meltdown.

In recent history, it has been the doctrine of the West to disseminate liberal capital market policies that have allowed large capital flows in both developed and developing countries. Capital market liberalization (CML) creates many issues despite the positive effects it has on development. Analogize capital flows into a country to deposits into a domestic bank. As long as one’s deposit, or in this case capital, is secure there is no concern, but if there is a loss of confidence in a country or domestic bank, investors will rapidly try to withdraw their assets. Individual countries, unlike banks, do not have deposit insurance and no way to control the flow of assets, which can lead to a massive outflow of capital similar to Asia in 1998. This every day example highlights a single risk behind CML there are several more. Firstly, this practice vastly increases the number of stakeholders in a domestic economy and can create instability if there is asymmetric access to information between investors.[22] This asymmetry is often the cause of speculative bubbles and, inversely, capital flight if there are poor economic indicators within a country. Globalization in this regard exemplifies the importance of external factors like foreign direct investment (FDI). Even countries with strong macroeconomic fundamentals can be adversely affected when, “sudden shifts in foreign capital flows…create financing difficulties in economic downturns.”[23] Furthermore, in globalized markets a relatively small downturn can have calamitous global effects, saliently demonstrated by the subprime mortgage crisis. These financial tremors are transmitted in three main ways: real links such as direct trade, financial links through the international financial system, and finally herding behaviour based on asymmetric information and the tendency for investors to, “infer future price changes based on how other markets are reacting.”[24] Capital market liberalization must occur concurrently with increases in transparency and a minimum standard of international financial reporting.

Emerging financial markets are of particular concern to global financial stability due to decreased regulation and the gravitational effect this low regulation has on financial intermediaries. These new financial markets in combination with increased, “[g]lobal financial integration produces the by-product of “regulatory arbitrage” [where] capital tends to flow to under-regulated countries, frequently resulting in excessive risk-taking, in anticipation of future bailout.”[25] The tendency for capital to flow to the least regulated area reinforces the necessity for a minimum level of international financial regulation to mitigate the global loopholes that allow for problematic levels of debt leveraging and risk-taking. These markets can also create global problems if their currencies are undervalued. As mentioned in the analysis of the current financial crisis, currencies below market value can lead to unsustainable consumption based on an artificially high domestic dollar and create trade imbalances by creating deflated export prices. “US policy-makers claim China’s currency is undervalued about 25 to 35% against the US dollar and they blame China for holding the value of the RMB [Yuan] weak to keep Chinese products competitive…in international markets.”[26] This practice is not specific to China and other developing countries have been accused of manipulating their currency to drive exports. This undervaluation is a major problem for developed countries like the US because in 2005, “China’s trade surplus reached a record $102 billion…while the US trade deficit of $717 billion accounted for 5.8% of US Gross Domestic Product in the same year.”[27] This trend removes liquid assets from the domestic economy and transfers them abroad where they can be used to invest in increasing foreign infrastructure that further perpetuates the cycle of domestic debt and cheap foreign exports.

The first two systemic risks, of capital market liberalization and emerging financial markets, are compounded by a lack of transparency in global markets. The problem with a lack of transparency arises primarily in the developing world because they have, “failed to couple capital account liberalization with requirements for transparency and disclosure, with prudential financial sector oversight, and with efforts to reduce corruption.[28] The pronounced lack of reliable reporting in some developing countries creates global information asymmetries that lead to the inefficient allocation of resources and occasional market failures as seen in the Asian financial crisis. Despite this, it must be noted that this lack of transparency is not exclusive to developing nations. A report published by the English House of Commons highlighted the “urgent need for enhanced transparency around complex financial products so that investors are able to undertake their own due diligence on the products they are investing in.”[29] In the current crisis there was a combination of insufficient transparency and a lack of due diligence on the part of stakeholders, almost to the point of willful blindness. The issue of transparency must include the inherent problems with securitization and complex financial products. The suitable level of transparency should transcend all areas of capital markets with specific attention to the creation of new financial products especially structured investment vehicles (SIV) due to their undefined composition and malleable configuration.

In the post crisis era there has been a great deal of global discussion regarding international financial regulation. As globalization decreases the distance between global financial markets, “the boundaries between domestic and global prudency regulation are getting fuzzier, calling for international coordination of minimum standards, where regulation would deal with risk exposure induced by large financial actors.”[30] Through the analysis of past crises, we can come to see that it is not an individual bubble at fault but the underlying systemic risks that provide a vehicle to influence other financial markets. Based on this, national governments and international governing bodies such as the IMF, should focus on mitigating these issues. Two of these, capital market liberalization and emerging financial markets, are not intrinsically problematic; it is when these risks are augmented by a lack of transparency that problems occur. The most substantial factor that leads to speculative bubbles and the spread of new crises is informational asymmetry and low transparency throughout the world. Establishing a minimum level of disclosure for macroeconomic indicators in a timely manner would reduce risk associated with volatile capital inflows and outflows within countries. The risks associated with emerging financial markets can also be reduced by increased transparency. If accurate levels of debt leveraging are disclosed within these markets and are limited, there will be reduced chance of default. Similarly, established financial markets must have adequate disclosure regarding the components of derivatives and complex financial products so the end-user knows the risks associated with such an investment. The issue of transparency transcends all other risks within the financial system and should be the focus of international initiatives addressing stability.

The global economy will undoubtedly continue to become further integrated both culturally and financially well into the future. As a global community, we must endeavour to implement a system that maximizes prosperity while minimizing systemic risk within the international financial system. Of equal importance is reducing the negative effects regulations have on market efficiency by carefully targeting policies. The Asian financial crisis and the current recession provided us with empirical evidence demonstrating that financial bubbles in themselves are not overtly dangerous. It is capital market liberalization, emerging financial markets, and low transparency that ultimately lead to global financial crises. Of these three it is the lack of transparency and the concurrent informational asymmetry that is of paramount importance for the causation of global crises. Given this, international governing bodies should focus on these key policy areas to ensure global stability. As stakeholders in the international financial system, we all must ensure that appropriate actions are taken to diminish these risks and induce symmetry within the international financial system.

Bibliography

Aizenman, Joshua. FINANCIAL CRISIS AND THE PARADOX OF UNDER- AND OVER-REGULATION. Rep. Cambridge: NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH, 2009. Print.

Branigin, William. “Consumer debt grows at alarming pace.” Msnbc.com. Washington Post, 12 Jan. 2004. Web. 5 Nov. 2009. <http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/3939463/>.

“Economic Roundup Issue 2, 2008 – Investment in East Asia since the Asian financial crisis.” Australian Government, The Treasury. Web. 4 Nov. 2009. <http://www.treasury.gov.au/documents/1396/HTML/docshell.asp?URL=02_East_Asia_investment.htm>.

Elliott, Douglas J. “Reviewing the Administration’s Financial Reform Proposals – Brookings Institution.” Brookings. 17 June 2009. Web. 1 Nov. 2009. <http://www.brookings.edu/papers/2009/0617_financial_reform_elliott.aspx>.

Financial Stability and Transparency. Rep. House of Commons Treasury Committee. Web. 6 Nov. 2009.

Fischer, Stanley. “Financial Crises and Reform of the International Financial System.” National Bureau of Economic Research (2002): 3. Print.

“IFC Treasury – Securitizations.” IFC Home. Web. 14 Nov. 2009. <http://www.ifc.org/ifcext/treasury.nsf/Content/Securitization>.

“The IMF’s Response to the Asian Crisis.” International Monetary Fund. Jan. 1999. Web. 1 Nov. 2009. <http://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/facts/asia.HTM>.

Jickling, Mark. Causes of the Financial Crisis. Issue brief. Congressional Research Service, 29 Jan. 2009. Web. 2 Nov. 2009. <http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/crs/r40173.pdf>.

Mosley, Layna. Regulating Globally, Implementing Locally: The Future of International Financial Standards. Rep. Waterloo: The Centre for International Governance Innovation, 2008. Print.

Ocampo, Jose, and Joseph Stiglitz, eds. Capital market liberalization and development. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

Peng, Tao, Minsoo Lee, and Christopher Gan. “As the Chinese currency than undervalued?” Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies 6.1 (2008): 49-50. Informaworld. Web. 6 Nov. 2009.

Pinsent, Wayne. “Credit Default Swaps: An Introduction.” Investopedia.com. Web. 5 Nov. 2009. <http://www.investopedia.com/articles/optioninvestor/08/cds.asp>.

Saxton, Jim. “The US Housing Bubble and the Global Financial Crisis.” US House of Representatives. Joint Economic Committee, May 2008. Web. 3 Nov. 2009. <http://www.house.gov/jec/news/Housing%20Bubble%20study.pdf>.

Soros, George. “Crash and Recovery.” NPQ Magazine. Scholars Portal. Web.

Figure 1

[1] Elliott, Douglas J. “Reviewing the Administration’s Financial Reform Proposals – Brookings Institution.” Brookings. 17 June 2009. Web. 1 Nov. 2009. <http://www.brookings.edu/papers/2009/0617_financial_reform_elliott.aspx>.

[2] Ibid

[3] “Economic Roundup Issue 2, 2008 – Investment in East Asia since the Asian financial crisis.” Australian Government, The Treasury. Web. 4 Nov. 2009. <http://www.treasury.gov.au/documents/1396/HTML/docshell.asp?URL=02_East_Asia_investment.htm>.

[4] “The IMF’s Response to the Asian Crisis.” International Monetary Fund. Jan. 1999. Web. 1 Nov. 2009. <http://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/facts/asia.HTM>.

[5] Ibid

[6] Fischer, Stanley. “Financial Crises and Reform of the International Financial System.” National Bureau of Economic Research (2002): 3. Print.

[7] “The IMF’s Response to the Asian Crisis.” International Monetary Fund. Jan. 1999. Web. 1 Nov. 2009. <http://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/facts/asia.pdf>.

[8] Soros, George. “Crash and Recovery.” NPQ Magazine. Scholars Portal. Web.

[9] Jickling, Mark. Causes of the Financial Crisis. Issue brief. Congressional Research Service, 29 Jan. 2009. Web. 2 Nov. 2009. <http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/crs/r40173.pdf>.

[10] Ibid

[11] Ibid

[12] Soros, George. “Crash and Recovery.” NPQ Magazine. Scholars Portal. Web.

[13] Jickling, Mark. Causes of the Financial Crisis. Issue brief. Congressional Research Service, 29 Jan. 2009. Web. 2 Nov. 2009. <http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/crs/r40173.pdf>.

[14] Saxton, Jim. “The US Housing Bubble and the Global Financial Crisis.” US House of Representatives. Joint Economic Committee, May 2008. Web. 3 Nov. 2009. <http://www.house.gov/jec/news/Housing%20Bubble%20study.pdf>.

[15] Ibid

[16] Saxton, Jim. “The US Housing Bubble and the Global Financial Crisis.”

[17] Branigin, William. “Consumer debt grows at alarming pace.” Msnbc.com. Washington Post, 12 Jan. 2004. Web. 5 Nov. 2009. <http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/3939463/>.

[18] Jickling, Mark. Causes of the Financial Crisis. Issue brief. Congressional Research Service, 29 Jan. 2009. Web. 2 Nov. 2009. <http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/crs/r40173.pdf>.

[19] “IFC Treasury – Securitizations.” IFC Home. Web. 14 Nov. 2009. <http://www.ifc.org/ifcext/treasury.nsf/Content/Securitization>.

[20] Jickling, Mark. Causes of the Financial Crisis. Issue brief. Congressional Research Service, 29 Jan. 2009. Web. 2 Nov. 2009. <http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/crs/r40173.pdf>.

[21] Pinsent, Wayne. “Credit Default Swaps: An Introduction.” Investopedia.com. Web. 5 Nov. 2009. <http://www.investopedia.com/articles/optioninvestor/08/cds.asp>.

[22] Stiglitz, Joseph. Capital market liberalization and development. Ed. Jose Ocampo. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

[23] Ibid

[24] Stiglitz, Joseph. Capital market liberalization and development. Ed. Jose Ocampo. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

[25] Aizenman, Joshua. FINANCIAL CRISIS AND THE PARADOX OF UNDER- AND OVER-REGULATION. Rep. Cambridge: NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH, 2009. Print.

[26] Peng, Tao, Minsoo Lee, and Christopher Gan. “As the Chinese currency than undervalued?” Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies 6.1 (2008): 49-50. Informaworld. Web. 6 Nov. 2009.

[27] Peng, Tao, Minsoo Lee, and Christopher Gan. “As the Chinese currency than undervalued?” Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies 6.1 (2008): 49-50. Informaworld. Web. 6 Nov. 2009.

[28] Mosley, Layna. Regulating Globally, Implementing Locally: The Future of International Financial Standards. Rep. Waterloo: The Centre for International Governance Innovation, 2008. Print.

[29] Financial Stability and Transparency. Rep. House of Commons Treasury Committee. Web. 6 Nov. 2009.

[30] Mosley, Layna. Regulating Globally, Implementing Locally: The Future of International Financial Standards. Rep. Waterloo: The Centre for International Governance Innovation, 2008. Print.

—

Written by: Chris Jones

Written at: University of Waterloo

Written for: Laszlo Sarkany

Date: 2009

This essay has been recognised with an e-IR Essay Award (Undergraduate)

Laszlo Sarkany

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Reform of the Global Financial Architecture: The Role of BRICS and the G20

- The Great Lockdown vs. The Great Depression and the 2008 Global Financial Crisis

- Agents of Change: Policy Entrepreneurs and Inducements in International Politics

- Legal ‘Black Holes’ in Outer Space: The Regulation of Private Space Companies

- Securitisation, China and FDI: The EU’s Foreign Direct Investment Screening Regulation

- To Reform the World or to Close the System? International Law and World-making