Few countries have drawn more concern than the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI), which is frequently regarded as a threat to international stability.[1] It is important, in the context of global religious revival, that we critically evaluate the assumptions that inflect these perceptions.[2] Such reflection has been, for the most part, absent from international relations scholarship.[3] In this paper, I take a constructivist approach to argue that anxieties over Iran are largely engendered by a binary tautology inherent in Westphalian internationalism that assumes international peace to be consonant with secularism and dissonant with religion.[4] This assumption is faulty for two reasons. First, it is contingent upon a particular occidental and Christian genealogy. This problematizes its own claims to universality.[5] Second, as a closer examination of Iranian politics and foreign policy demonstrates, this view’s rigid dualism is largely faulty. Although the IRI has contravened international norms, it is erroneous to see this as a necessary outcome of its theocratic government.[6] Rather, Tehran’s foreign policy reflects the pluralism of the regime’s political-theological discourse. Westphalian assumptions promote an ignorance of this pluralism and lead to the incorrect assumption that a theocratic Iran is incompatible with international stability.[7] This viewpoint establishes and maintains barriers to détente and cooperation between Iran and Western state actors.[8]

This argument is developed through several sections. I first trace the genesis of the Westphalian system in relation to the particular secular tautology this paper addresses. I then examine the pluralism that animates Iranian foreign relations. Finally, I argue that American diplomacy regarding Iran has largely overlooked this pluralism and instead responded to Iran as a prima facie opponent.

It is first important, however, to situate the argument made here within international relations theory. The dominant theories of international relations, neo-realism and neo-liberalism, typically take for granted international secularism and hypothesize about patterns of behavior within the international system so defined.[9] As such, social constructivism is a theory better suited to the study of the norms that lay at the foundation of the relationship between religion and international relations. As Michael Barnett explains, constructivism “is more broadly concerned with how to conceptualize the relationship between agents and structures.”[10] This theory views international order as a sphere of social interaction in which specific intersubjective norms structure relations.[11] In the contemporary international order, these norms are largely secular and occidental in origin.[12]

WESTPHALIAN SECULARISM

Secularism may be defined as a social modality whereby religion is excluded from various spheres of social interaction.[13] Politically, this is where religion is rejected from spaces of political deliberation.[14] Secularism often claims a post-metaphysical neutrality and normative superiority over the non-secular.[15] In addition to the connections drawn between secularism and modernity, democracy and capitalism, international, or Westphalian, secularism further claims itself as the foundation of international peace and stability.[16]

Prior to 1648 political authority in Europe was essentially held concurrently by the Church and feudal lords.[17] The contemporary international order came about as a response to the European wars of religion, which have been attributed to religion as combatants ostensibly battled apostasy following the Protestant Reformation.[18] The 1648 Peace of Westphalian, which ended these conflicts, established three precepts that still define conventional international society. First, states became sovereign actors. This was associated with the principle of rex est imprator in regno suo (‘whose the region his the religion’), which asserted that rulers may not intervene in one another’s domestic politics on religious grounds.[19] Similarly, the treaty also codified the principle of cujus regio ejus religio (‘the king is supreme in his own realm’), which held that political authority is independent of the metaphysical.[20]. Finally, the Westphalian Peace formally propounded the separation of church and state between and within states themselves.[21] The Peace of Westphalia essentially created a new international order and excluded the religious from it. As Hurd explains,

the conflicts of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries inverted the dominance of the ecclesiastical over the civil authority through the creation of the modern state, preparing the way for the eventual elimination of the church from the public sphere.[22]

The Westphalian order was subsequently imposed upon the world through colonialism and even countries like Iran, which were never fully colonized, were forced to conform to these norms.[23]

The genealogy of Westphalian secularism means that religion is either overlooked in international relations or summarily and uncritically seen as unpredictable, illogical, and menacing.[24] As Carlson and Owens state,

this formula is particularly dangerous when it is adopted by statespersons, foreign policy experts, political scientists, theorists, and journalists who then find themselves working without an interpretive framework that properly accounts for religious perspectives and their moral influences.[25]

Essentially, the assumptions associated with Westphalian secularism encourage the belief that states must follow a western trajectory of secularism to assure international stability.[26]

REVOLUTIONARY IRAN

The fallacious heuristics engendered by this binary tautology is evident in the conventional perceptions of Iran and, more generally, political Islam. In the Iranian case, the plurality of opinion regarding the state’s foreign policy tends to be overlooked. Instead, relevant actors are lumped into a theocratic rogues’ gallery of international dissidents.[27] In order to understand the dynamics of Iranian theological pluralism, it is first important to understand political Islam and the Iranian state’s origins and structures.

Political Islam. Islamism supports the union of political and religious authority and seeks to create policy in accordance with religious principles.[28] As Saidabadi explains, Islamism is distinct from neo-fundamentalism in that the latter often pursues an isolationist agenda and avoids politics while Islamists,

view Islam and religious authority as primary, and the state as their instrument. They argue that religious authority should form government and that political authority should form religious authority in society. Adhering to the unity of religion and politics, [political Islamists] believe that the government has to be Islamic and the leadership has to be religious […] Unlike [neo-fundamentalists] they do not want to be isolationists, but believe that Islam has all the requirements ad capacity to manage a government and direct […] its foreign relations.[29]

Iran is one of the only examples of such a theocratic system in practice.[30] The sui generis nature of Iran’s theocracy means that while investigation yields insights into the nature of contemporary international society, these findings may not be generalizable to other states or non-state religious actors.

The Iranian Revolution. Although Shah Reza Pahlavi’s regime forbade dissent, a diverse coalition solidified around the religious leadership of the exiled Grand Ayatollah Sayyed Ruhollah Mousavi Khomeini.[31] It is indicative of the uncritical faith in secularist schemas that, though Khomeini’s movement had been developing since the 1950s, western states did not perceive this religious coalition as a significant political force; this would have violated the teleological assumptions regarding secular modernity.[32] In 1977, for instance, President Jimmy Carter stated that Iran was an “island of security,” and American diplomatic and intelligence services had written Khomeini off.[33] In 1979, however, the revolutionary coalition was able to depose the Shah and an Islamic state was subsequently establish in which the Qur’an and Sunna became constitutionally protected and established as the sole legitimate authority.[34] This theocracy subsequently marginalized secular members of the revolutionary coalition and established Khomeini in a dominant position.[35]

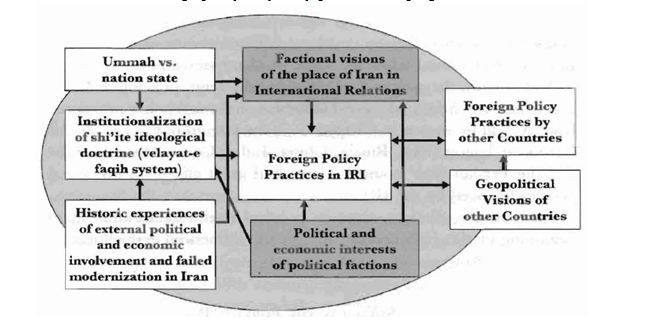

Revolutionary Iran is a major vector through which Islam and Westphalian international society have met, and this has had seismic implications for Westphalian secularism. Iran is frequently essentialized as a dangerous international dissident .[36] The inaccuracy of these assumptions, however, is belied by a closer examination of Iran. In fact, The IRI’s foreign policy has fluctuated between challenging international society and conforming to it. These vacillations are the result of theological and doctrinal heterogeneity.

Iranian Foreign Policy Structures. The most important institution regarding foreign policy is the Iranian Constitution, which formally binds the conduct of diplomacy to the Qur’an and Sunna. It establishes seven principles regarding the conduct of foreign policy. The first principle, Omm-al Qora, is the protection of the Islamic state. A related second principle, Nafy Sabil, declares that Iran may not cede its sovereignty to foreign actors. For instance, article 152 states,

the foreign policy of the Islamic Republic of Iran is based upon the rejection of all forms of domination, both the exertion of it and submission to it, the preservation of the independence of the country.[37]

Similarly, article 153 states,

any form of agreement resulting in foreign control over the natural resources, economy, army, or culture of the country, as well as other aspects of national life, is forbidden.[38]

Third, political leaders are officially allowed some latitude within Islamic precepts in the name of expediency. Fourth, peaceable relations will be pursued with states that are not hostile to Iran or Islam in general. This is stated in Article 152,

the foreign policy of the Islamic republic of Iran is… [obliged to] the maintenance of mutually peaceful relations with all non-belligerent states.[39]

The fifth and sixth principles require that Iranian foreign policy serve as a vector of da’wa (‘proselytization’) beyond its borders. Finally, the Iranian Constitution pledges fealty to all Muslims irrespective of citizenship.[40] While the first four principles are consonant with Westphalian norms, the final three are more contentious. However, the relative importance given to these principle and their interpretations has differed markedly depending on who holds specific nodes of power.[41]

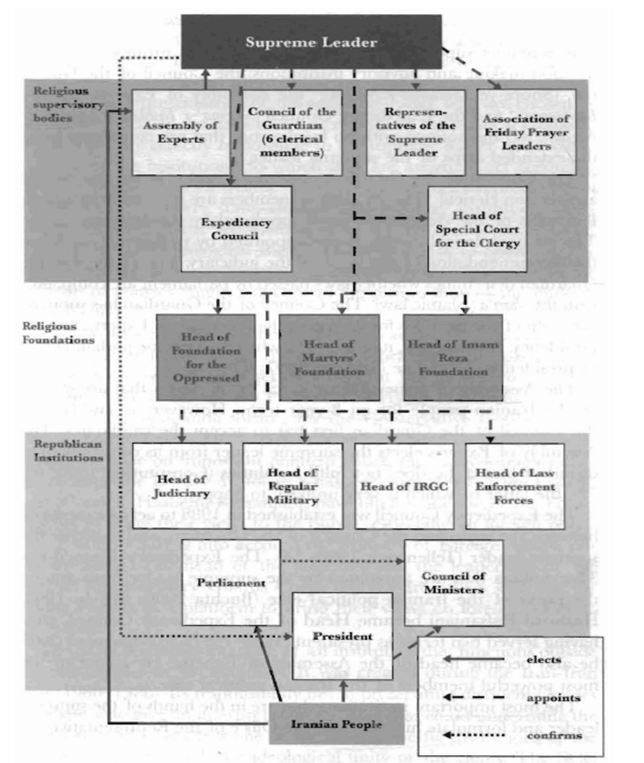

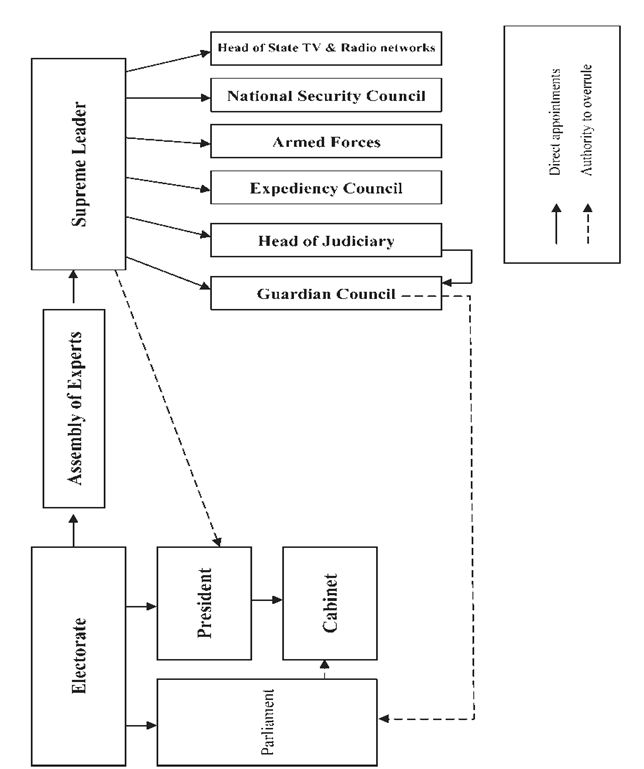

Article 110 gives jurisdiction over foreign policy to the Velayat-e Faqih, or supreme leader (figures 1, 2).[42] While it is typically assumed that the IRI’s foreign policy is dictatorial and hierarchically oriented, there are actually numerous nodes in the Iranian foreign policy network which allow factional contenders to influence diplomacy.[43] As Adam Tarock points out,

there […] are layers of authorities and a certain degree of pluralism, though not necessarily in the western tradition. It is that pluralism, albeit an Islamic version of it, which [western states] either find difficult or unwilling to come to terms with the case of Iran.[44]

The various nodes include, but are not limited to: the Velayat-e Faqih and the Guardianship Council over which he presides; the President and cabinet; the Minister and Ministry of Foreign Affairs; the National Security Council; the Majlis (Iran’s Legislature); the Expediency Council (an advisory and intermediary organ); the military and paramilitary Revolutionary Guard; and, the media, discourse elite, and general public.[45] This institutional pluralism has encouraged the development of doctrinal pluralism and political factions which are loosely bound by compatible political-theologies, as formal political parties are prohibited in the IRI.[46] Despite this prohibition, elected officials frequently run on platforms associated with a particular faction.[47]

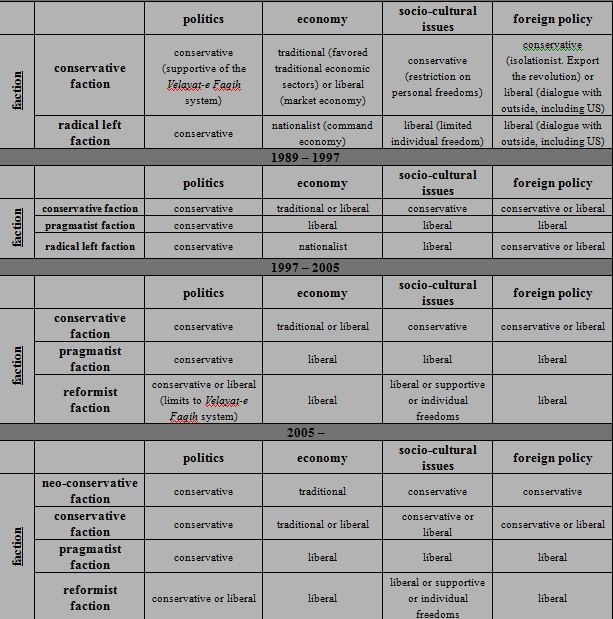

There are three dominant factions in the Iranian system, each espousing a distinct foreign policy approach: conservatives, pragmatists, and reformers (figure 3).[48] These factions cannot be said to represent a conflict between western-style modernity and religious traditionalism; rather, they are contests oriented around different religious doctrines, trajectories of modernity and tradition, notions of community, and differing concepts of authority which occur within a larger theocratic framework that is generally accepted as legitimate (figure 4).[49] Further, it is important to note that these factions reflect schisms within the Iranian population itself: twenty-five to thirty percent are conservative, forty to forty-five percent are floating reformist-pragmatists, ten percent are committed pragmatists, and twenty to twenty-five percent are simply apathetic.[50]

The Conservatives and Iran’s Jacobin Era (1979-1989). The conservatives originally nucleated around Khomeini and reached their zenith of power during the jacobin decade that followed the revolution. It is important to note that this factions is still central, owing to conservatives’ control of the Guardianship Council.[51]

Theologically, conservative hardliners support the view that political authority needs to be utilized to regulate social life and impose conformity with the Qur’an and Sunna.[52] This faction also adheres to a distinct foreign policy approach. As Saidabadi explains, foreign affairs for this group is,

founded on the argument that Iran’s foreign policy makers are duty bound to determine Iran’s foreign policy subject to the fulfillment of Islamic principles, without thought for long term consequences… the conduct of Iran’s foreign policy should not take current realities into account.[53]

Since Khomeini’s leadership, conservative foreign policy has been based on two such principles: na sharq na gharb (‘neither east not west’) and ‘export of the revolution.’[54] Although the former has been, and continued to be, conveyed in religious terms as independence from America (‘the Great Satan’) or the USSR (‘the Lesser Satan’), Iran’s pursuit of political independence from foreign powers is consonant with Westphalian norms and had been a diplomatic objective of pre-revolution Iran.[55]

The latter objective, however, has posed a much greater challenge to Westphalian norms. The goal of exporting the revolution gives primacy to and reflects a specific interpretation of those constitutional principles which see the state as a vector for the conduct of da’wa. This proselytizing mission has been threatening to Westphalian norms because it not only rejects the legitimacy of conventional Westphalian sovereignty, but also because it sees the Velayat-e Faqih as presiding over the entire Umma (Muslim community) as would an Imam.[56] As Khomeini stated,

we should try hard to export our revolution to the world… because Islam does not regard various Islamic countries as differently and is supporter of all the oppressed… we [shall] confront the world with our ideology.[57]

In practice, exporting the revolution amounted to a policy of supporting Shi’ite Islamists in other countries.[58] This stance threatened many Middle Eastern leaders, whose claims to legitimacy are not ostensibly Islamic. For instance, relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia became particularly acrimonious during this period. Not only did Khomeini state that Saudi Arabia’s monarchy was un-Islamic, but also supported Shi’ite protests in Saudi Arabia, most notably during the 1987 Hajj (‘pilgrimage’).[59] This is clearly dissonant with notions such as cujus regio ejus religio and rex est imprator in regno suo. Furthermore, this Jacobin attempt to export the revolution clearly inflected international stability, most notably leading to the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988) in which numerous western and middle eastern states supported secular Ba’athist Iraq while Iran portrayed the conflict as a manichean religious struggle.[60] This form of revolutionary challenge to the international system is not, of course, only seen in theocracies. For instance, a similar diplomatic emphasis on spreading the revolution was also evident following the Russian Revolution of 1917.[61]

The Pragmatists and Iran’s Thermidore Period (1989-1997). The pragmatist faction became ascendant under the Presidency of Hojjat Al-Islam Ali-Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani during the post-revolutionary thermidore. This was related to three factors. First, Khomeini’s successor, Grand Ayatollah Ali Koseyni Khamenei, lacked Khomeini’s political largess and ability to impose consensus.[62] A second factor was the burgeoning of a moderate post-revolutionary generation which has been less interested in perpetual revolutionary struggle.[63] Finally, there was a need to reconstruct after the war with Iraq.[64]

Pragmatists espouse a particular theology which differentiates them from conservatives. Like conservatives, pragmatists see the Qur’an and Sunna as the sole source of legitimate authority. However, unlike conservatives, they prioritize domestic revolutionary consolidation over exportation and argue that in order to achieve this goal, Iran must constructively engage the world. This has to do with an interpretation of Omm-al Qora, which brings the principle closer to Westphalian notions of rational raison d’état.[65] For instance, shortly after his inauguration, Rasfanjani sent a communiqué to the European Community that stated,

the Islamic Republic of Iran is committed to international law, opposes interference in the internal affairs of other states, recognizes the observance of domestic laws as a democratic move and denounces the use of force in international relations.[66]

Although the pragmatists’ foreign policy aimed at rapprochement with other Middle Eastern states, its distinctive agenda is clearest with regard to Central Asia.[67] Although the Central Asian states are largely secular, owing to their soviet history, Tehran has not attempted to export its revolution or displace secular leaders. Instead, its diplomacy is largely based on national interest.[68] For instance, Tehran prioritized material interests over religion when mediating the Nargorno-Karbakh War between Azerbaijan and Armenia. Despite Azerbaijan’s Shi’ite majority, Tehran remained neutral and, at times, even supported Christian Armenia so as to deny Turkish influence in the region.[69] A similar example is Iran’s effort to arbitrate conflict between Tajikistan’s secular government and Islamist challenger groups.[70]

Despite the pragmatists’ ascendancy, however, Iran’s multiple nodes of power militate against a decisive shift away from jacobinism and have created a more complex and contradictory diplomacy following Khomeini’s death. For instance, while Rafsanjani pursued relations with Europe, other elites were carrying out assassinations of dissidents in European countries.[71] This incoherence has continued into the reformist Presidency of Hojjat Al-Islam Sayyid Mohammad Khatami and beyond.

The Reformist Era (1997-2005). The same factors that contributed to the ascendency of the pragmatists subsequently led to reformist dominance under the Khatami Presidency.[72] Theologically, reformists are distinct from both the conservatives and pragmatists in that they have sought to decrease the state’s social control and limit the power of the supreme leader by making the theocratic government more accountable to the electorate.[73] Western media and scholarship has often portrayed Reformists as secularists; this, however, overlooks their deep commitment to religious values.[74] This group is largely concerned with innovation in domestic, rather than foreign, policy. In terms of diplomacy, they tend to see international rapprochement as supportive of this domestic agenda. Khatami essentially continued Rafsanjani’s diplomatic initiatives, especially repairing regional relations. For instance, the IRI’s relationship with Saudi Arabia was closely attended to and has warmed greatly.[75] One important agenda that distinguished reformist from pragmatist foreign policy has been an emphasis on mending fences with the west. The most notable such effort was Khatami’s ‘dialogue of civilizations.’[76] This constitutes a major break with the more belligerent conservative notions of na sharq na gharb.[77] As Ramazani explains, “perhaps the most important result of Khatami’s conciliatory policy, devoid of ideological baggage, has been Iran’s expanding ties with Europe.”[78] Furthermore, the IRI publically denounced the 9/11 attacks and indirectly aided the American intervention in Afghanistan. However, these efforts at reconciliation were greatly undercut by Khamenei who has, with the backing of the Revolutionary Guard, continued to support Islamist groups in such as Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in Palestine.[79]

Importantly, the reformist period also saw the US invasion of Afghanistan (2001) and Iraq (2003).[80] Under Khatami, Iran developed a relationship with the Karzai administration in Afghanistan.[81] In Iraq, the IRI has supported democratization in tandem with the deployment of religious soft-power in order to facilitate the development of a more pliable Shi’ite majority or, at the very least, prevent Iraq from becoming an American or Saudi rump state.[82] This has occasionally brought Iran into agreement with America. For instance, Tehran supported the US-backed Iraqi National Congress.[83] As with other agendas, Khatami’s involvement in Iraq has been continuously undermined by the conservatives. In this case, Khamenei has portrayed Khatami as a comprador for his congenial attitude toward America.[84]

Neo-Conservatives and the Jacobin ‘Revival’ (2005-). From 2004, reformist influence has declined.[85] Khatami has stated the reformists’ defeat owed to the machinations of the hojjateh, a cabal of hard-line neo-conservatives.[86] Khamenei, who is conservative rather than neo-conservative, largely engineered this shift. In 2004, for instance, the Guardianship Council disqualified some 3,600 Majlis candidates who had supported Khatami.[87] The election of Ahmadinejad, a hardline neo-conservative, to the presidency in 2005 is a clear reflection of the conservatives’ reclamation of power. In terms of foreign policy, Ahmadinejad has argued that Iran has not gone far enough in exporting the revolution and has claimed authority over the entire Ummah, as Khomeini had also done.[88] The contemporary conservative position, however, is more ambiguous than in the halcyon days of the revolution. This is because Ahmadinejad actually has relatively little control over diplomacy relative to Khamenei. This ambiguity is also due to Khamenei’s attempts to play the pragmatists and conservatives off each other so as to bolster his own position.[89] Ahmadinejad’s radicalism allows Khamenei to appeal to both pragmatists and conservatives by moderating the former.[90] On the one hand, when Rafsanjani, who now heads the Expediency Council at Khameini’s pleasure, demanded the removal of Ahmadinejad from office, Khamenei defused this by increasing Rafsanjani’s and his own power. On the other hand, Khamenei has publically blessed some of Ahmadinejad’s more belligerent statements.[91] This political dynamic allows Khamenei maximal latitude.[92]

The dominant diplomatic issues for Iran are currently Iraq, the larger Middle East, and the nuclear program.[93] It is unclear that Ahmadinejad dominates any of these issue areas. Iran’s policy toward Iraq will likely to continue as it has thus far. Iran and America have even recently had their first official meetings since 1979 over the issue of Iraqi reconstruction.[94] Yet, the neo-conservatives may spoil Khamenei and Rafsanjani’s more pragmatic approach. For example, while mainstream Iranian factions have denounced Muqtada al-Sadr, an Iraqi Shi’ite agitator, neo-conservative factions have continued to support him through the Revolutionary Guard.[95] However, American diplomatic blunders have meant that both jacobin and pragmatic approaches to the Middle East are temporarily compatible. Iran’s increased anti-Israel rhetoric, for example, has not alienated regional allies, even those won during the Khatami period such as Saudi Arabia.[96] This is not to say that Iranian conservatism is accepted by all. Egypt’s foreign minister, for instance, publically stated after Ahmadinejad’s election that the Egyptian government would resist any attempt to export revolution into that country.[97]

Similarly, Ahmadinejad has little influence over the nuclear program and no authority to declare war. As in other policy areas, there is a plurality of opinions regarding the nuclear program, few of which share Ahmadinejad’s apparently apocalyptic inclinations.[98] Yet, his messianic and eschatological statements regarding an impending nuclear war have complicated perennially combative relations with the west and the United States in particular, a relationship that three-quarters of Iranians would like to seem improved.[99]

AMERICAN-IRANIAN RELATIONS

From the revolution and the 1979-1981 hostage crisis, relations between Iran and America have been antipathetic.[100] This is surprising considering that, in terms of Westphalian raison d’état, neither country benefits from this conflict. The Iranian economy is greatly harmed by American embargoes while American oil companies lose billions of dollars annually.[101] America’s seemingly unshakable enemy image of Iran is strongly beholden to its cultural and normative relationship to the Westphalian system.[102] As Hurd explains, the Westphalian assumptions have

formed the conceptual apparatus through which Americans framed the revolution… The American laicist perspective on Iran was a consequence of an often unacknowledged intellectual and visceral commitment to a particular formation of secular modernity… More than any single factor, the authoritative forms of secularism […] account for the visceral antipathy vis-à-vis Iran and the Iranian Revolution.[103]

America has consequently often overlooked the dynamism at play in Iranian foreign policy and has instead summarily judged the IRI as threatening. For instance, the Clinton Administration imposed some of the strongest sanctions upon Iran, such as the ‘dual-containment’ strategy against Iran and Iraq and the Iran-Libya Sanction Act (1996), during its thermidore period. Similarly, President Bush placed Iran on the ‘axis of evil’ during the reformist era.[104] Wester states appear to have difficulty accepting the dynamism of the Iranian theocracy. Through a tautological lense, it is impossible that Iran should be both emulate and oppose western modernity or, as Tarock says, “they can be idealists and pragmatists at the same time.”[105] Thus, Washington has continuously pushed for regime change in Tehran.[106] This perception effectively blinds America to diplomatic opportunities for engaging Iranian pragmatists or reformers in ways that may advance both countries’ diplomatic objectives.

CONCLUSION

America’s, and much of the west’s, uncompromising foreign policy stance toward the IRI is closely linked to those norms and assumptions that form the basis of the international order.[107] The Iranian case suggests that there may be nothing ‘natural’ about the secular international order. Rather, the international order is bound by norms and notions that are inherently intersubjective and contingent on cultural genealogies.[108] It is important to critically investigate these assumptions as they form the basis of foreign policy formulation.

The tautologies upon which Westphalian secularism is constructed are premised on rigid distinctions between secularism and religion.[109] As the Iranian case demonstrates, this Westphalian tautology may be fallacious.[110] On the one hand, it is clear that religion, specifically the Christian heritage of the Westphalian system, has influenced international order in ways that contradict its own foundational ideology.[111] On the other hand, the result of Westphalian secularism’s occidental genealogy supports the prima facie judgment that religion poses a threat to international stability. This overlooks the pluralism that exists in systems such as the IRI. In this sense, Westphalian assumptions support the related perceptions of such states, or religiously motivated groups, as monolithic and inherently threatening to international peace. Rather, as Iranian diplomatic pluralism demonstrates, there is no inherent or necessary relationship between its theocracy and conflict.[112] This analysis is consonant with Hayne’s finding that religion, though it certainly has an impact on diplomacy, has no clearly negative or unidirectional impact on international stability.[113] This suggests that contemporary international society will likely have to move beyond those assumptions which informed its own creation if it is to peaceably accommodate the present-day religious revival.[114]

APPENDIX

Figure 1: the formal power structure of the Islamic Republic of Iran since the 1979 revolution.

Source: Eva Patricia Rakel, Power, Islam, and Political Elite in Iran: A Study on the Iranian Political Elite from Khomeini to Ahmadinejad, (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2009), 33

_______________

Figure 2: The formal power structure of the Islamic Republic of Iran since the 1979 revolution.

Source: Shahram Akbarzedah, “Where is the Islamic Republic of Iran Heading?” in Australia Journal of International Affairs 59, 1 (2005): 28

_______________

Figure 3: Positions of political-theological factions in the Islamic Republic of Iran by time period and issue area.

|

|||||

Source: Eva Patricia Rakel, Power, Islam, and Political Elite in Iran: A Study on the Iranian Political Elite from Khomeini to Ahmadinejad, (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2009), 51-52, 54, 56, 61.

_______________

Figure 4: Important factors bearing, questions, and issues bearing upon the Islamic Republic of Iran’s foreign policy trajectory, practices and programme.

Source: Eva Patricia Rakel, Power, Islam, and Political Elite in Iran: A Study on the Iranian Political Elite from Khomeini to Ahmadinejad, (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2009), 23

_______________

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran,” [foreign policy], (Tehran: Irano-British Chamber of Commerce, n.d.), <http://www.ibchamber.org/lawreg/constitution.htm>, (accessed, 15 April 2010)

Afrasaibi, Kaveh and Abbas Maleki, “Iran’s Foreign Policy After 11 September,” in Brown Journal of World Affairs 9, 2 (Winter/Spring, 2003): 255-265

Akbarzedah, Shahram, “Where is the Islamic Republic of Iran Heading?” in Australian Journal of International Affairs 59, 1 (2005): 25-38

Appleby, R Scott, “Serving Two Masters? Affirming Religious Belief and Human Rights in a Pluralistic World,” in the Sacred and the Sovereign: Religion and International Politics, (eds.) John D Carlson and Eric C Owens, pp 170-195 (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2003)

Barnett, Michael, “Social Constructivism,” in The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations, third edition, (eds.) John Baylis and Steve Smith, pp 251-270 (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 205)

Beehner, Lionel, “Iran’s Multifaceted Foreign Policy,” (New York and Washington: Council on Foreign Relations, April 7, 2006), http://www.cfr.org/publication/10396/, (accessed April 11, 2010)

Bilgin, Pinar, “Thinking Past ‘Western’ IR,” in Third World Quartlery 29, 1 (2008): 5-23

Carlson, John D and Eric C Owens, “Introduction: Reconsidering Westphalia’s Legacy for Religion and International Politics,” in the Sacred and the Sovereign: Religion and International Politics, (eds.) John D Carlson and Eric C Owens, pp 1-37 (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2003)

Chubin, Shahram, “Iran’s Power in Context,” in Survival 51, 1 (2009): 165-190

Chubin, Shahram, Iran’s National Security Policy: Intentions, Capabilities, and Impact (Washington, DC: the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1994)

Dark, Ken R, “Large-Scale Religious Change and World Politics,” in Religion and International Relations, (ed.) Ken R Dark, pp 55-82 (New York and London: St. Martin’s Press Inc and MacMillan Press Ltd., 2000)

Durham, Martin, “The American Right and Iran,” in The Political Quarterly 79, 4 (October-December, 2008): 508-517

Fox, Jonathan and Shmuel Sandler, Bringing Religion into International Relations (New York: Palgrave-MacMillan, 2004)

Fuller, Graham E, The ‘Center of the Universe’: The Geopolitics of Iran (Boulder: The RAND Corporation, 1991)

Green, Jerrold D, Frederick Wehrey, and Charles Wolf Jr, “Understanding Iran” (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2009)

Hatzopoulos, Pavlos and Fabio Petito, “The Return from Exile: An Introduction,” in Religion in International Relations: The Return from Exile, (eds.) Fabio Petito and Pavlos Hatzopoulos, pp 2-20 (New York: Palgrave-MacMillan, 2003)

Haynes, Jeffery, An Introduction to International Relations and Religion (Harlow: Pearson Education Limited, 2007)

Haynes, Jeffrey, “Religion and Foreign Policy Making in the USA, India, and Iran: Towards a Research Agenda,” in Third World Quarterly 29, 1 (2008): 143-165

Hurd, Elizabeth Shakman, “The International Politics of Secularism: US Foreign Policy and the Islamic Republic of Iran,” in Alternatives 29, (2004a): 115-138

Hurd, Elizabeth Shakman, “The Political Authority of Secularism in International Relations,” in European Journal of International Relations 10, 2 (June, 2004b): 235-263

Hurd, Elizabeth Shakman, The Politics of Secularism in International Relations (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008)

Jackson, Robert J and Patricia Owens, “The Evolution of the International System,” in The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations, third edition, (eds.) John Baylis and Steve Smith, pp 46-62 (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2005)

Rakel, Eva Patricia, “Iranian Foreign Policy Since the Iranian Islamic Revolution: 1979-2006,” in Perspectives on Global Development and Technology 6, 1-3 (2007): 159-188

Rakel, Eva Patricia, Power, Islam, and Political Elite in Iran: A Study on The Iranian Political Elite from Khomeini to Ahmadinejad (Lieden: Koninklijke Brill, 2009)

Saidabadi, Mohammed Reza, “Islam and Foreign Policy in the Contemporary Secular World: The Case of Post-Revolutionary Iran,” in Global Change, Peace, and Security 8, 2 (1996): 32-44

Taremi, Kamran, “Iranian Foreign Policy Towards Occupied Iraq, 2003-2005,” in Middle East Policy 12, 4 (Winter, 2005): 28-47

Tarock, Adam, Iran’s Foreign Policy Since 1990: Pragmatism Supersedes Islamic Ideology (Commack, NY: Nova Science Publishers Inc., 1999)

Thomas, Scott M, The Global Resurgence of Religion and the Transformation of International Relations: The Struggle for the Soul of the Twenty-First Century (New York: Palgrave-MacMillan, 2005)

Thomas, Scott, “Religion and International Conflict,” in Religion and International Relations, (ed.) Ken R Dark, pp 1-23 (New York and London: St. Martin’s Press Inc and MacMillan Press Ltd., 2000)

Wendt, Alexander, “Constructing International Politics,” in International Security 20, 1 (Summer, 1995): 71-81

Wyatt, Christopher M, “Islamic Militancies and Disunity in the Middle East,” in in Religion and International Relations, (ed.) Ken R Dark, pp 100-113 (New York and London: St. Martin’s Press Inc and MacMillan Press Limited, 2000)

[1] Jeffery Haynes, An Introduction to International Relations and Religion (Harlow: Pearson Education Limited, 2007), 7; Lionel Beehner, “Iran’s Multifaceted Foreign Policy,” [Introduction] (New York and Washington: Council on Foreign Relations, April 7, 2006), http://www.cfr.org/publication/10396/, (accessed April 11, 2010); Mohammed Reza Saidabadi, “Islam and Foreign Policy in the Contemporary Secular World: The Case of Post-Revolutionary Iran,” in Global Change, Peace, and Security 8, 2 (1996): 37; Graham E Fuller, The ‘Center of the Universe’: The Geopolitics of Iran (Boulder: The RAND Corporation, 1991), 267

[2] Scott M Thomas, The Global Resurgence of Religion and the Transformation of International Relations: The Struggle for the Soul of the Twenty-First Century (New York: Palgrave-MacMillan, 2005), 33; Ken R Dark, “Large-Scale Religious Change and World Politics,” in Religion and International Relations, (ed.) Ken R Dark, pp 55-82 (New York and London: St. Martin’s Press Inc and MacMillan Press Ltd., 2000), 63; John D Carlson and Eric C Owens, “Introduction: Reconsidering Westphalia’s Legacy for Religion and International Politics,” in the Sacred and the Sovereign: Religion and International Politics, (eds.) John D Carlson and Eric C Owens, pp 1-37 (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2003),1, 9; Jonathan Fox and Shmuel Sandler, Bringing Religion into International Relations (New York: Palgrave-MacMillan, 2004), 11-12; Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, The Politics of Secularism in International Relations (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008), 1, 110; Haynes (2007), 3, 19, 33, 39, 97-98, 113, 115

[3] Pavlos Hatzopoulos and Fabio Petito, “The Return from Exile: An Introduction,” in Religion in International Relations: The Return from Exile, (eds.) Fabio Petito and Pavlos Hatzopoulos, pp 2-20 (New York: Palgrave-MacMillan, 2003), 2-3; Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, “The Political Authority of Secularism in International Relations,” in European Journal of International Relations 10, 2 (June, 2004b): 240; Eva Patricia Rakel, Power, Islam, and Political Elite in Iran: A Study on The Iranian Political Elite from Khomeini to Ahmadinejad (Lieden: Koninklijke Brill, 2009), xxiv, xxv; Carlson and Owens, 8-9; Thomas (2005), 3; Hurd (2008)15, 23, 33; Haynes (2007), 3, 115

[4] Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, “The International Politics of Secularism: US Foreign Policy and the Islamic Republic of Iran,” in Alternatives 29, (2004a): 115; Hurd (2008), 1, 16, 33; Haynes (2007), 8, 106; Hurd (2004b), 240; Carlson and Owens, 8

[5] Pinar Bilgin, “Thinking Past ‘Western’ IR,” in Third World Quartlery 29, 1 (2008): 5, 8; Dark, 50; Adam Tarock, Iran’s Foreign Policy Since 1990: Pragmatism Supersedes Islamic Ideology (Commack, NY: Nova Science Publishers Inc., 1999), 38

[6] Eva Patricia Rakel, “Iranian Foreign Policy Since the Iranian Islamic Revolution: 1979-2006,” in Perspectives on Global Development and Technology 6, 1-3 (2009): 187; Shahram Chubin, Iran’s National Security Policy: Intentions, Capabilities, and Impact (Washington, DC: the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1994), 67; Shahram Akbarzedah, “Where is the Islamic Republic of Iran Heading?” in Australian Journal of International Affairs 59, 1 (2005): 25-26, 32; Rakel (2009), xxvii; Fuller, 268

[7] Christopher M Wyatt, “Islamic Militancies and Disunity in the Middle East,” in in Religion and International Relations, (ed.) Ken R Dark, pp 100-113 (New York and London: St. Martin’s Press Inc and MacMillan Press Ltd., 2000) 101; Haynes (2007), 54, 356; Rakel (2009), 147; Akbarzadeh, 25-26, 31-32

[8] Hurd (2008), 118, 122

[9] Hurd (2008), 32; Haynes (2007) 35-36; Bilgin, 11; Rakel (2009), 20-21

[10] Michael Barnett, “Social Constructivism,” in The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations, third edition, (eds.) John Baylis and Steve Smith, pp 251-270 (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 205), 258

[11] Alexander Wendt, “Constructing International Politics,” in International Security 20, 1 (Summer, 1995): 71, 73; Hurd (2004a), 118; Hurd (2008), 14

[12] Haynes (2007), 105

[13] Haynes (2007), 8; Hatzopoulos and Petito, 2

[14] Dark, 53-58

[15] Hurd (2004a), 115, 117-118, 131; Hurd (2004b), 236, 238; Rakel (2009), 1; Dark, 53; Fox and Sandler, 11; Hurd (2008), 13, 15; Haynes (2007), 20

[16] Hurd (2008), 14-15, 23-25, 30; Carlson and Owens, 7, 9, 15-16; Haynes (2007), 100

[17] Carlson and Owens, 13

[18] Haynes (2007), 31; Carlson and Owens, 14

[19] Robert J Jackson and Patricia Owens, “The Evolution of the International System,” in The Globalization of World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations, third edition, (eds.) John Baylis and Steve Smith, pp 46-62 (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 54

[20] Ibid.

[21] Thomas (2005), 33; Carlson and Owens, 16; Haynes (2007), 31-32; Jackson and Owens, 52-53

[22] Hurd (2008), 31; Hatzopoulos and Petito, 1-2; Haynes (2007) 31, 108; Jackson and Owens, 53

[23] Hurd (2008), 24; Haynes (2007), 6, 31; Scott Thomas, “Religion and International Conflict,” in Religion and International Relations, (ed.) Ken R Dark, pp 1-23 (New York and London: St. Martin’s Press Inc and MacMillan Press Ltd., 2000), 18; Bilgin 16-17

[24] Haynes (2007), 107; Hatzopoulos and Petito, 1; Carlson and Owens, 6; Thomas (2000), 14, 18; Dark, 50; Hurd (2004a), 129; Hurd (2004b), 235; Bilgin, 11

[25] Carlson and Owens, 8; also see Dark, 52; Bilgin, 10-11; Hurd (2004b) 118. 244-246

[26] Hurd (2008), 118, 122

[27] Hurd (2004a), 119, 122;

[28] Fox and Sandler, 90; Saidabadi, 35-36; Hurd (2008), 87, 117; Wyatt, 104; Saidabadi, 34

[29] Saidabadi, 33

[30] Ali Gheissari and Vali Nasr, “Iran’s Democracy Debate,” in Middle East Policy 11, 2 (Summer, 2004): 91Fox and Sandler, 49-50; R Scott Appleby, “Serving Two Masters? Affirming Religious Belief and Human Rights in a Pluralistic World,” in the Sacred and the Sovereign: Religion and International Politics, (eds.) John D Carlson and Eric C Owens, pp 170-195 (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2003), 16; Jeffrey Haynes, “Religion and Foreign Policy Making in the USA, India, and Iran: Towards a Research Agenda,” in Third World Quarterly 29, 1 (2008): 156-157; Rakel (2009), 3-4; Saidabadi, 37;

[31] Hurd (2008), 15; Hurd (2004a), 120-123

[32] Thomas (2005), 2

[33] Hurd (2004a), 127; Hurd (2008), 106-107; Haynes (2007), 354; Haynes (2008), 156-157; Fox and Sandler, 11-12, 134; Thomas (2005), 1

[34] “The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran,” [foreign policy], (Tehran: Irano-British Chamber of Commerce, n.d.), <http://www.ibchamber.org/lawreg/constitution.htm>, (accessed, 15 April 2010) (see article 1); also see Saidabadi, 36-37; Akbarzadeh, 25

[35] Haynes (2007) 354-355; Haynes (2008), 156; Hurd (2004a), 122; Rakel (2009), xxiv; Saidabadi, 34, 36; Akbarzadeh, 28

[36] Haynes (2007), 356; Hurd (2008), 108

[37] “The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran,” (see chapter ten, article 152)

[38] “The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran,” (see chapter ten, article 153)

[39] “The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran,” (see chapter ten, article 152)

[40] Saidabadi, 37-38; Jerrold D Green, Frederick Wehrey, and Charles Wolf Jr, “Understanding Iran” (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2009), 9

[41] Haynes (2007), 54, 357; Rakel, xxi

[42] ”The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran,” (see article 110)

[43] Rakel (2009), xxii; Haynes (2007), 54; Tarock, 37-39

[44] Tarock, 40; also see Rakel (2007), 164

[45] Tarock, 37-39; Rakel (2007), 165; Rakel (2009), 149; Haynes (2007), 54; Haynes (2008), 157-158; Beehner [Who sets Iranian Foreign Policy?], [Which other government bodies influence Iran’s foreign policy?]

[46] Green, Wehry, and Wolf, 6, 25; Rakel (2009), xxiii-xxiv, 32, 40

[47] Rakel (2009). 3, 42, 52

[48] Green, Wehry, and Wolf, 25; Rakel (2009), 43

[49] Rakel (2009), xxiv, 21-23; Thomas (2005), 11; Hurd (2004), 16-117

[50] Tarock, 35; Rakel (2007), 181

[51] Saidabadi, 40-41; Green, Wehry, and Wolf, 25-27; Rakel (2007), 166; Rakel (2009), xxi, 46, 52; Gheissari and Nasr, 94

[52] Rakel (2009), 51-52; Green, Wehry, and Wolf, 26; Hurd (2004), 126

[53] Saidabadi, 40; also see RK Ramazani, “Ideology and Pragmatism in Iran’s Foreign Policy,” in Middle East Journal 58, 4 (Autumn, 2004): 549, 555; Rakel (2007), 167

[54] Rakel (2007), 160, 167; Rakel (2009), 22; Saidabadi, 41; Tarock (1999), 3; Ramazani, 555-556

[55] Tarock, 3-4, 60; Rakel (2009), 153, 159-160

[56] Ramazani, 555; Fox and Sandler, 50; Tarock, 4; Rakel (2009), 25, 153; Chubin (1994), 121; Saidabadi, 40

[57] Tarock, 16; also see Rakel (2009), 153; Ramazani, 556-557

[58] Fox and Sandler, 64, 71-72, 89; Thomas (2000), 6, 18-19; Rakel (2009), 154-155

[59] Tarock, 16, 19-20; Rakel (2007), 167-170

[60] Kamran Taremi, “Iranian Foreign Policy Towards Occupied Iraq, 2003-2005,” in Middle East Policy 12, 4 (Winter, 2005): 31; Shahram Akbarzedah, “Where is the Islamic Republic of Iran Heading?” in Australian Journal of International Affairs 59, 1 (2005): 173-174; Rakel (2007), 165; Tarock, 4, 17;

[61] Fuller, 97

[62] Tarock, 1; Chubin (1994), 67; Rakel (2009), xxiv, xxvi, 54; Rakel (2007), 157; Gheissari and Nasr, 95; Haynes (2008),157; Akbarzadeh, 27, 33

[63] Akbarzadeh, 30; Rakel (2009), 4, 54

[64] Haynes (2007), 355; Tarock, 1; Saidabadi, 43

[65] Tarock, 1, 4, 38; Saidabadi, 39, 42; Rakel (2007), 166, 170, 177; Rakel (2009), 163; Gheissari and Nasr, 95; Fuller, 267; Chubin (1994), 67; Ramazani, 556; Green, Wehrey, and Wolf, 26-27

[66] Saidabadi, 42

[67] Haynes (2007), 5; Tarock, 125; Rakel (2007), 75-76

[68] Rakel (2009), 164-168; Tarock, 127-128; Fuller, 97

[69] Kaveh Afrasaibi and Abbas Maleki, “Iran’s Foreign Policy After 11 September,” in Brown Journal of World Affairs 9, 2 (Winter/Spring, 2003): 257; Tarock, 132, 135-138; Rakel (2009), 164, 171

[70] Tarock, 130-132

[71] Rakel (2007), 169

[72] Haynes (2007), 355; Rakel (2007), 178; Akbarzadeh, 30; Beehner [introduction]

[73] Appleby, 183; Rakel (2009), 56-57; Green, Wehrey, and Wolf, 26

[74] Thomas (2005), 3

[75] Afrasiabi and Maleki, 258

[76] Rakel (2007), 157

[77] Rakel (2009), 175-177; Ramazani, 557

[78] Ramazani, 558; also see Tarock, 29

[79] Rakel (2007), 179; Haynes (2008), 157; Ramazani, 557-558; Akbarzadeh, 34

[80] Afrasiabi and Maleki, 255; Rakel (2009), 177

[81] Akbarzadeh, 34; Afrasiabi and Maleki, 259

[82] Taremi, 32; Haynes (2007), 357-358

[83] Akbarzadeh, 35

[84] Chubin, 66; Akbarzadeh, 35; Chubin (2009), 175

[85] Akbarzadeh, 31-32; Haynes (2007), 356; Rakel (2009), 66; Taremi, 30, 32; Gheissari and Nasr, 102-103

[86] Haynes (2007), 357

[87] Gheissari and Nast, 104

[88] Martin Durham, “The American Right and Iran,” in The Political Quarterly 79, 4 (October-December, 2008): 509; Rakel (2007), 181; Rakel (2009), 22, 57, 66, 187-188; Akbarzadeh, 31; Haynes (2008), 158-159; Chubin (2009), 175; Beehner, [What is the outlook of these government officials]

[89] Beehner, [What is the outlook of these government officials], [What is the role of the Iran’s president in foreign relations?]; Haynes (2007), 356-357; Green, Wehrey, and Wolf, 7; Chubin (2009), 175; Rakel (2007), 181

[90] Green, Wehrey, and Wolf, 8; Rakel (2007), 182

[91] Chubin (2009), 171

[92] Rakel (2009),61-63, 67; Green, Wehrey, and Wolf, 10

[93] Haynes (2008), 157; Rakel (2009), xxv

[94] Haynes (2007), 358; Haynes (2008), 159; Rakel (2009), 57. 196; Akbarzadeh, 34

[95] Taremi, 37-38

[96] Green, Wehrey, and Wolf, 8-9; Chubin (2009), 170, 176; Haynes (2008), 160; Rakel (2009), 190

[97] Chubin (2009), 172, 174, 181

[98] Rakel (2007), 184-185

[99] Rakel (2007), 184; Haynes (2008), 160; Durham, 509; Rakel (2009), 196

[100] Hurd (2004), 125; Hurd (2008), 102-103; Tarock, 5, 33, 36, 38; Fox and Sander, 50, 72; Thomas (2000), 3; Rakel (2009), 176; Chubin (2009), 166; Afrasiabi and Maleki, 261; Durham, 508, 512-513; Akbarzedah, 34

[101] Tarock, 33

[102] Hurd (2008), 103-104

[103] Hurd (2008), 107, 110; also see Chubin (2009), 167; Hurd (2004), 120; 128

[104] Thomas (2005), 214; Rakel (2009), 172; Tarock, 34

[105] Tarock, 35; also see, Beehner, [What is the outlook of these government officials?]

[106] Rakel (2009), 196

[107] Hatzopoulos and Petito, 1

[108] Haynes (2007), 37

[109] Hurd (2008), 16, 33; Carlson and Owens, 9

[110] Tarock, 35; Thomas (2005), 10

[111] Dark, 50; Tarock, 38; Bilgin, 5, 8

[112] Wyatt, 101, 106, 108

[113] Haynes (2007), 116, 356

[114] Hatzopoulos and Petito, 2; Carlson and Owens, 8; Fox and Sandler, 1

—

AUTHOR: Ryan Morrow

DATE WRITTEN: April 23rd, 2010

LECTURER: Professor Ruth Marshall

INSTITUTION: University of Toronto

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Puzzle of U.S. Foreign Policy Revision Regarding Iran’s Nuclear Program

- To Reform the World or to Close the System? International Law and World-making

- Turning Domestic into Political: The Case of Female Self-immolation in Iran

- Rogue Relations under Max-Pressure: Iran-Venezuela Bilateral Engagement 2013–2020

- Indian Perspective on Iran-China 25-year Agreement

- Feminist Approaches to International Relations: ‘Good Girls’ Only?