Introduction

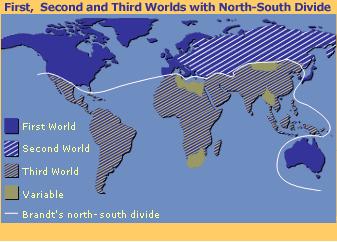

A clearly defined development gap separates the globe in two parts: the North, which includes the developed or industrialized nations and the South, which includes all the developing nations from the emerging economies of Brazil, India, and China to the least developed countries (LDCs) like Nepal and Bangladesh. The South encompasses about 130 countries. On the other hand, the North includes North America (Canada and the United States), Europe, Russia, Australia, and New Zealand (see map 1 in annex). According to a United Nations report for the General Assembly (2009), “the world population of over 6 billion people [is divided] into a two-thirds majority of poor people, living mostly in Africa, Asia and Latin America, and an affluent one third, living mostly in the industrialized societies of Europe, North America and parts of Australasia” (p.22). Of these two-thirds, many live in poverty, lack human and food security, and do not have access to the same technological and financial resources of the global North. A call for development for all has been a prominent feature of United Nations (UN) conferences, especially with such agencies as the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Historically, the South has depended on the North for development aid, financial resources, and trade in exports and imports, especially in terms of natural resources. This has further ingrained the dependence of these nations and has prevented economic diversification in many countries, as is the case with many oil and natural gas exporting nations such as Nigeria and Venezuela.

In the new millennium, the idea of South-South Cooperation has recently become more popular, especially due to the continued widening of the development gap and the seeming failure of North-South development strategies. South-South Cooperation can be defined as

a process whereby two or more developing countries pursue their individual or collective development through cooperative exchange of knowledge, skills, resources and technical expertise. […] South-South cooperation is multidimensional in scope and can include all sectors and kinds of cooperation activities among developing countries, whether bilateral or multilateral, subregional, regional or interregional (UNDP, 2007, p. 1)

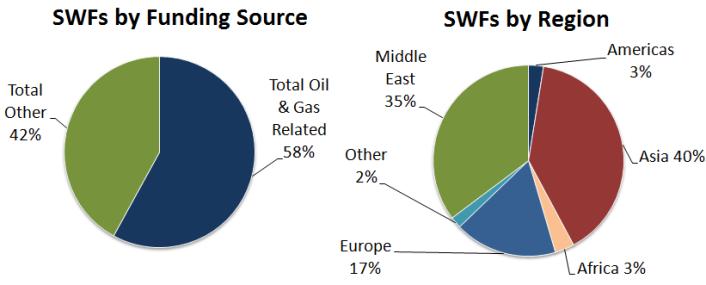

It is a development initiative based on the exchange of resources, technology, and knowledge among nations of the global South towards other nations within the group. In 1978, the UN Conference on Technical Cooperation among Developing Countries enacted the Buenos Aires Plan of Action, which establishes an overall objective “for developing countries to foster national and collective self-reliance by promoting cooperation in all areas. The aim is to supplement, not supplant, cooperation with developed countries” (UN General Assembly, 2009, p.3). It sought to complement South-South Cooperation with North-South Cooperation. Today, South-South Cooperation reemphasizes this concept and has taken on new forms. Increasing trade, foreign direct investment (FDI), development aid, and technology transfer mark the economic and political relationships amongst the Southern nations. “A number of developing and transition economies have recently surfaced as important home countries of FDI. Between 1990 and 2005, the number of such economies with outward stocks of FDI of more than US$5 billion increased from 6 to 25” (UNCTAD Press Office, 2006). In the past, these links were much weaker. Today sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) can also be added to this South-South equation. The biggest funds can be found in nations of the South, specifically China and Middle Eastern nations such as the United Arab Emirates. These new resources represent a new way forward for the South as they will bring much needed investment in many areas such as infrastructure, development, and technology transfer, whilst also increasing the economic links between the nations of the South. They have the potential of reducing South-North dependency and propelling sustainable development forward in these regions. However, SWFs are known for a lack of transparency and for their possible use as state tools to undermine economic competition. They are state-controlled funds, which can be used for strategic reasons that serve the interests of the origin nation, but might not necessarily benefit the overall development of the global South. The main challenges will be to ensure that these SWFs do not increase the economic dependency of the South on other Southern nations and that a lack of transparent policies does not hinder the potential development initiatives of some of these funds.

Emergence of Sovereign Wealth Funds

SWFs have existed since the 1950s and 1960s, however in recent years the role of SWFs has become more prominent (for a listing of the top 16 SWFs, see table 1 in annex). SWFs total about “$2–3 trillion and, based on the likely trajectory of current accounts, could reach $10 trillion by 2012” (Johnson, 2007, p.56) of all available financial assets around the world. While, this number is not very high when compared to the number of other financial flows and funds, many controversies have arisen around the role that these funds can play in the global economy. An SWF is a “state-owned investment fund composed of financial assets such as stocks, bonds, real estate, or other financial instruments funded by foreign exchange assets” (Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute, 2010). SWFs investments have generally been beneficial for both host and recipient countries. They allow SWF holders to stabilize their economy and reinvest their assets in both developed and developing nations and their own domestic economy. This was the case during the 2008 financial crisis when “some $40 billion [from SWFs] was poured into distressed Western lenders, among them Citigroup, UBS, Morgan Stanley and Merrill Lynch” (The Economist, 2009). SWFs can also play a critical role within the country itself, as was the case when the Kuwait Investment Authority Fund invested in the Gulf Bank as part of a rescue plan. The aim was to have these shares resold to the public at a later date (El Gamal, 2009). The financial crisis and the emerging BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) economies have brought SWFs to the forefront of many newspapers and international journals.

SWFs encompass large amounts of foreign reserves, which originate from commodity exports such as oil and natural gas or non-commodities such as assets accumulated from foreign exchange reserves. Since their management is handled by the State, they are very politicized funds. The Economist (2008) described them as tools “to influence prices and markets.” Their lack of transparency and publication causes concern among many nations. In fact, there have been cases when SWFs were prohibited from investing in certain sectors. This was the case when “politicians in Washington came out in strong opposition to Cnooc’s [China National Offshore Oil Corporation] efforts to win Unocal [Union Oil Company of California], saying the state-owned oil company was acting as a proxy for the Chinese government and seeking to secure strategically valuable U.S. energy assets” (Barboza, 2005). Oil is a key strategic sector within the domestic economy of any nation. Its control by another sovereign power would represent a national security risk. Overall, SWFs investments may represent a security risk due to their lack of transparency and published portfolios. According to an International Monetary Fund (IMF) economist, their future success “lies in greater clarity in disseminating timely information on sovereign wealth funds’ objectives, overall strategy, and medium-term evaluation metrics” (El-Erian, 2010). After the 2008 financial crisis, the presence of SWFs became very controversial and lead to a call for the establishment of voluntary principles to govern their application. The IMF published the Santiago principles, which recommend guiding principles for the operation of SWFs. The aim is to “contribute to the stability of the global financial system, reduce protectionist pressures, and help maintain an open and stable investment climate” (IWG, 2008, p.4). The key question of these financial flows is whether or not these challenges outweigh the benefits.

For the South, a lack of transparency might not necessarily concern these nations as the need for development is critical and can override security concerns. The numerous benefits that SWFs can bring to the investor nation as well as the recipient nation are quite varied. Knowledge and technology transfer, long-term capital investments, and possibilities of economic diversification represent much needed resources for the developing South. However, SWFs carry their own political weight; these economic benefits need to be measured in terms of the investing State’s strategic interests. The context under which SWFs will play an important role in South-South Cooperation will depend on the abilities of the Southern nations to embrace these new financial flows. Already, they are playing a big role: most SWFs are located in the South (see table 1 in annex) and thus the South benefits from investments made throughout the globe. However, it is important to note that South-South Cooperation has its own sets of challenges, which will affect the role SWFs may play in the South’s future economic development.

Benefits and Challenges of South-South Cooperation

South-South Cooperation encompasses many benefits. In particular, development projects with neighboring countries have been enacted under this cooperation movement. The shared understanding of development challenges among the South aids business initiatives and permits investors to take risks, where they otherwise would not have. Many North investors refrain from ventures in the South due to unstable political and economic environments. For example, concerns that a business might be nationalized or that a political regime might be overthrown prevent investors from truly committing to a project of any kind. South-South Cooperation “is thus viewed by those participating in it from the perspective of political solidarity of the South, utilisation of complementarities between developing countries and direct cooperation between larger developing countries and other countries in the South” (Yu, 2009). An exchange among equals in both the political and cultural realms allows for increased cooperation. This is unlike the relationship existent between the North and the South. Elizabeth Lord, an Economic and Scientific Affairs Officer at the United States Mission in Geneva, described South-South Cooperation as a “means for these markets to open up to one another” (personal communication, February 4, 2011). Unfortunately, this solidarity does not always counteract the lack of stable economic and political environments in the South. This unstable environment has the potential of affecting SWFs future investments. However, the BRICS’ economic growth has lead to further development for the entire region and outweighed some of these risks. For example,

in 2009 China became the leading trade partner of Brazil, India and South Africa. The Indian multinational Tata is now the second most active investor in sub-Saharan Africa. Over 40% of the world’s researchers are now in Asia. As of 2008, developing countries were holding USD 4.2 trillion in foreign currency reserves, more than one and a half times the amount held by rich countries (OECD, 2010, p. 15)

Many of the global assets are beginning to move amongst the global South nations and not just towards the North, thus increasing development prospects and the abilities of the South to further diversify their economies.

Nowadays, South-South trade and financial flows are on the rise. “Last year, transnational corporations (TNCs) based in developing or transition economies, but excluding major offshore financial centres, generated FDI outflows of $120 billion – the highest level ever recorded” (UNCTAD Press Office, 2006). South-South is a growing trend and indicates a strong relationship between South-South nations, especially when taking into consideration the emerging economies of the BRICS. In fact, “during the 1990s, South-South foreign direct investment flows grew faster than North-South flows” (UNDP, 2007, p. 3). The increase in South-South FDI indicates the possible emergence of new norms for development, which defy the traditional model that FDI and Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) can only come from the North. The BRICS are becoming dynamic regional centers of growth and have continued to strategically promote South-South cooperation. However, “Indian officials and industrialists have expressed concern that India’s exports to China are predominantly raw materials, whereas trade in the other direction is of manufactures which are undercutting India’s small and medium-sized businesses” (OECD, 2010, p.160). Going forward, this will become a critical challenge for South-South Cooperation: how to avoid the dependency pitfalls that occurred with North-South development? SWFs will aid the South in avoiding these pitfalls.

The Role of SWFs in South-South

South-South Cooperation represents an exchange among equals, an opportunity for investments and trade to take place between nations who share similar political, social, and economic conditions. As has already been mentioned, investors in the South are more likely to invest in other nations of the South due to this shared understanding. This is where SWFs can play a critical role in promoting development and a new way forward. “As politically motivated restrictions on investments by oil-rich countries intensify in the West, the sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) of the Gulf countries could opt to invest in Asia and other emerging markets despite attractive valuations in the slowing U.S and European markets” (Janardhan, 2008, p.5). South SWFs holders are moving a share of their investments from the developed North and directing them towards the South, where they are most likely to benefit overall economic development. Since the financial crisis, “sovereign wealth funds are at an advantage when it comes to managing the bumpy journey to the new normal: their stable and patient capital and long-term orientation in investment objectives put them in an excellent position to make a first move” (El-Erian, 2010). Other published cases can be seen with the China-Africa Development Fund, which has invested in 27 development projects in Africa (Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute, 2008), and the Abu Dhabi Investment Company, which has shares in the Iraq Opportunity Fund and an Emerging Africa Fund (Abu Dhabi Investment Company, 2009). Examples such as these clearly demonstrate the value of SWFs within South-South relations. Economic diversification, long-term capital growth, investments instead of aid, and access to new and better technologies are some of the benefits that SWFs can bring to both their host and recipient countries. A positive consequence of these benefits would be the long-term stability of the State: where there are investments, services are provided, education and work is available, security becomes a norm, and development can occur.

However, SWFs are not without their own set of challenges. A lack of transparency not only affects the global North, but can also affect the South. SWFs are critical for South-South relations as much as they are for the North. However, national sovereignty concerns are of paramount importance. SWFs are seen as violating the sovereignty of other nations. They invest in key strategic sectors such as banks and energy, which raises serious security concerns due to the lack of transparency. On the other hand, this concern can be disregarded when infrastructure and development projects take place, as is the case with the China-Africa Development Fund. It represents a double-edge sword: investments are needed; yet the geopolitical and geoeconomic interests of other States need to be considered before investment can become acceptable.

Another challenge will be the diversification of the investment portfolios of SWFs from the North to the South. Due to the economic and political stability of the North, States face less investment risks and may also gain Northern knowledge and technology, which can then be reinvested in their own nations. In the long-run, the potential benefit of this knowledge and technology transfer could spread from one South nation to another as SWFs nations continue to invest in other parts of the South. This particular challenge brings both negative and positive aspects for the SWF State. On the other hand, SWFs have accrued large capital gains (see table 1 in annex). Since many SWFs have originated from countries exporting raw materials, in particular oil and gas, these potential savings will allow them to prepare for a rainy day. This can clearly be seen in the example of Kiribati, “a Pacific island country that mined guano for fertiliser, [and] set up the Kiribati Revenue Equalisation Reserve Fund in 1956. Today the guano is long gone, but the pile of money remains. If it manages a yield of 10% a year, the $400m fund stands to boost the islands’ GDP by a sixth” (The Economist, 2008). Investing these savings has the potential of diversifying their economies or promoting other economic projects to gain further capital, whilst also aiding development in other Southern nations or within their own nations. The fact that natural resource exporters and BRICS economies are reinvesting in their own regions will lead to further interdependence within the South and many positive benefits for the global South. A United Nations General Assembly Resolution noted

the significant increase and expanded use of South-South cooperation by developing countries as an important and effective instrument of international cooperation, and in this connection urges developing countries in a position to do so to intensify technical and economic cooperation initiatives at the regional and interregional levels in areas such as health, education, training, agriculture, science and new technologies, and in particular information and communication technologies (2002, p. 2)

SWFs represent the path through which these technical and economic cooperation initiatives may be strengthened. Investments in other South nations permit technology sharing, infrastructure construction, and an increase in overall financial flows towards different sectors of the economy.

A New Way Forward for the South

SWFs are mostly located in the Asian and Middle Eastern economies (see graph 1 in annex). The Asian economies, in particular China, are rapidly expanding and in search of natural resources for their continued growth. This will easily lead towards future investments in other South nations, particularly those in Africa and Latin America. SWFs could lead to future moves away from ODA and could supplement traditional FDI. Less dependence on the North will permit these nations to diversify their economies in conjunction with partners seeking the same goals. Market access would be amplified with neighboring countries thus lowering the import and export duties as transportation costs are lower (and if there is a regional agreement in place, customs duties are eliminated or are lowered considerably). SWFs also have the potential of furthering economic diversification beyond the primary sectors and into the secondary and tertiary sectors. The transfer of knowledge and technology from the North and even amongst the South is key towards achieving this. SWFs can fulfill this role. In today’s globalized world, South-South Cooperation cannot be easily separated from North-South Cooperation; however, the two should not be treated symmetrically and less dependency on the North could lead to further economic diversification and establish stronger economies. In fact, “South-South FDI could become a vehicle for technology transfer, especially when compared to North-South FDI, where there has not been a lot of evidence of real technology transfer” (R. Kozul-Wright, personal communication, January 27, 2011). Thus it is critical for the South to move away from ODA and accept long-term sustainable investments such as SWFs that can create jobs, increase production, and benefit the society overall.

SWFs’ “ability in many circumstances to take a long-term view in their investments and ride out business cycles brings important diversity to the global financial markets, which can be extremely beneficial, particularly during periods of financial turmoil or macroeconomic stress” (IWG, 2008, p.3). They go beyond meeting present needs and establish a stronger base to meet future needs. Hence, the critical role SWFs can play within South-South Cooperation. Perhaps, SWFs’ benefits on South-South Cooperation will lead to the establishment of a new type of economic order, where States strategically seek to promote development in partner nations to create greater market access for their own exports, while also increasing their own financial reserves. SWFs holders will be able to increase their savings for a rainy day. On the other hand, SWFs recipients will have an opportunity to economically diversify, develop, and perhaps even set up their own SWFs to save for their own rainy day.

Conclusion

The benefits of SWFs outweigh the challenges within South-South Cooperation, at least for the time being. Concerns over violation of sovereignty rights are quickly dissipated when the value of SWFs investments are clearly seen. Greater transparency, as called for in the IMF Santiago Principles, would certainly increase the great benefits of SWFs for recipient nations, in particular the global South. To lessen economic dependency, investments in different infrastructures and sectors are needed along with reduction in the reliance of ODA. SWFs will allow for increased long-term investment and technology transfer, which will both lead to economic diversification. The coming years will certainly prove their value, especially as trade and FDI continue to increase between Southern nations. SWFs, which mostly originate in Southern nations, will establish another financial link between the global South and allow for increased cooperation. “The South should not rely on SWFs for financing development anymore than on other capital inflows. However, there is a real challenge to re-channel the resources of SWFs into development opportunities in countries that require it, and to augment domestic resource mobilisation” (R. Kozul-Wright, personal communication, January 27, 2011). Other factors outside of SWFs such as technology transfer and continued cooperation with the North will continue to be critical for the development of the global South. SWFs will play an important role in further fomenting this relationship and allowing partners of equal status to share their experience and learn from their mistakes. “The increase in South-South resource flows creates opportunities for poor developing countries in particular, since the investors concerned and the banks are clearly familiar with the technological requirements and actual cultural and political conditions and are far more willing to take risks than investors from industrialized countries” (Chahoud, 2007, p. 4). They also bring in the much-needed financial resources that the South is generally lacking in many nations. “More efficient government investment potentially means more government money. For the countries making the investments, this could translate into lower taxes, better public works, and stronger state-run businesses. For resource-exporting states concerned about long-term economic viability, SWFs also present a possible source of sustainable long-term capital growth” (Teslik, 2009). If South-South Cooperation initiatives are strengthened and SWFs’ portfolios are diversified, economic development for these nations would lead to the dawn of a new economic order, where the global South is on equal social and economic terms with the global North.

References

Abu Dhabi Investment Company (2009). Asset Management. Retrieved January1 5, 2011 from http://www.investad.ae/en/Investments/AssetManagement.aspx

Anonymous (2011). Personal Communication. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Economic Cooperation and Integration among Developing Countries Unit.

Barboza, David (2005). China backs away from UNOCAL bid. The New York Times. Retrieved February 1, 2011 from http://www.nytimes.com/2005/08/02/business/worldbusiness/02iht-unocal.html

Chahoud, Tatjana (2007). South-South Cooperation – Opportunities and Challenges for International Cooperation. German Development Institute: Briefing Paper 09/2007. Retrieved December 20, 2010 from http://www.die-gdi.de/CMS-Homepage/openwebcms3_e.nsf/(ynDK_contentByKey)/ADMR-7BLF2V/$FILE/9%202007%20EN.pdf

El-Erian, Mohamed A. (2010). Sovereign Wealth Funds in the New Normal. International Monetary Fund: Finance and Development, Volume 47, Issue #2, Retrieved February 1, 2011 from http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2010/06/erian.htm

IWG: International Working Group of Sovereign Wealth Funds (2008). Sovereign Wealth Funds: Generally Accepted Principles and Practices: ‘Santiago Principles’. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved February 1, 2011 from http://www.iwg-swf.org/pubs/eng/santiagoprinciples.pdf

Johnson, Simon (2007). The Rise of Sovereign Wealth Funds: We Don’t Know Much about These Major State-owned Players. International Monetary Fund: Finance and Development, Vol. 44: 3. pp. 56-57. Retrieved February 1, 2011 from http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2007/09/pdf/straight.pdf

Kozul-Wright, R. (2011). Personal Communication. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Economic Cooperation and Integration among Developing Countries Unit.

Lord, E. (2011) Personal Communication. United States Mission to the United Nations in Geneva, Switzerland.

OECD: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2010). Perspectives on Global Development 2010: Shifting Wealth. OECD Development Centre. Retrieved December 22, 2010 from http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/perspectives-on-global-development-2010/the-increasing-importance-of-the-south-to-the-south_9789264084728-9-en;jsessionid=3fgvdkkndosi8.delta

El Gamal, Rania (2009). Kuwait Sovereign Fund takes Stake in Gulf Bank. UK Reuters. Retrieved January 15, 2011 from http://uk.reuters.com/article/2009/01/26/gulfbank-kia-idUKLNE50P06220090126

Janardhan, Meena (2008). Sovereign Wealth Funds to Invest in Asia. InterPress Service News Agency: South-South Executive Brief, Vol. 1: 7, p.5. Retrieved February 1, 2011 from http://ipsnews.net/south-south/SSTV7.2.pdf

Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute (2008). China- Africa Development Fund. Retrieved January 15, 2011 from http://www.swfinstitute.org/fund/cad.php

Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute (2010). What are SWFs? About Sovereign Wealth Funds. Retrieved January 15, 2011 from http://www.swfinstitute.org/what-is-a-swf/

Teslik, Lee Hudson (2009). Sovereign Wealth Funds. Council on Foreign Relations: Backgrounder. Retrieved January 15, 2011 from http://www.cfr.org/international-finance/sovereign-wealth-funds/p15251

The Economist (2008). Sovereign Wealth Funds: Asset-backed Insecurity: Wall Street, the flagship of capitalism, has been bailed out by state-backed investors from emerging economies. That has people worried—for good reasons and bad. Briefings 2. Retrieved January 15, 2011 from http://www.economist.com/node/10533428

The Economist (2009). Banks and Sovereign Wealth Funds: Falling Knives: The Smart and the Not-so-smart. Finance and Economics. Retrieved January 15, 2011 from http://www.economist.com/node/15065731

UNDP: United Nations Development Program (2007). Evaluation of UNDP Contribution to South-South Cooperation. A.K. Office Supplies: United States of America. Retrieved January 15, 2011 from http://www.undp.org/evaluation/documents/thematic/ssc/SSC_Evaluation.pdf

UNCTAD: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Press Office (2006). Booming South-South Investment Creates Development Opportunities, says UNCTAD. [Press Release]. Retrieved January 5, 2011 from http://www.unctad.org/templates/webflyer.asp?docid=7459&intItemID=3642&lang=1

UNCTAD: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2010). Economic Development in Africa Report 2010: South-South Cooperation: Africa and the New Forms of Development Partnership. Retrieved January 15, 2011 from http://www.unctad.org/templates/webflyer.asp?docid=13329&intItemID=5491&lang=1&mode=downloads

U.N. General Assembly, 56th Session (2002). Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on the report of the Second Committee: Economic and Technical Cooperation Among Developing Countries. (A/RES/56/202). 21 February, 2002. Retrieved January 15, 2011 from http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/56/202

U.N. General Assembly, 64th Session (2009). Promotion of South-South Cooperation for Development: A Thirty-year Perspective: Report of the Secretary-General (A/64/504). 27 October 2009. Retrieved January 15, 2011 from http://ssc.undp.org/uploads/media/A_64_504__final_version_.pdf

Yu, Vincent Paulo III (2009). S-S Cooperation Should be Defined by the South. South Centre. Retrieved February 8, 2011 from http://www.southcentre.org/ARCHIVES/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1246&Itemid=287

Bibliography

Alden, C., Morphet, S. & Viera, M. (2010). The South in World Politics. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.

Avendaño, R. & Santiso, J. (2009). Are Sovereign Wealth Funds’ Investments Politically Biased? A Comparison with Mutual Funds. OECD Development Centre: Working Paper # 283. Retrieved January 5, 2011 from http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/download/fulltext/5kmn1b9sk3nv.pdf?expires=1297542891&id=0000&accname=guest&checksum=49198A5C93A42B1F6CA8889AEF50365F

Bortolotti, B. & Miracky, W. (Eds.). (2009). Weathering the Storm: Sovereign Wealth Funds in the Global Economic Crisis of 2008. Monitor & Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei. Retrieved February 1, 2011 from http://www.monitor.com/Portals/0/MonitorContent/imported/MonitorUnitedStates/Articles/PDFs/Monitor-FEEM_SWF_Weathering_the_Storm_04_2009.pdf

Csurgai, Gyula (2009). Sovereign Wealth Funds: Strategies of Geo-Economic Power Projections. In Otto Hieronymi (ed.), Globalization and the Reform of the International and Banking and Monetary System, (pp. 209-227). United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.

Curto, Stefano (2010). Sovereign Wealth Funds in the Next Decade. The World Bank, The Economic Premise note series No 8. pp. 239- 349. Retrieved January 10, 2011 from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTPREMNET/Resources/C14TDAT_239-250.pdf

ECOSOC: United Nations Economic and Social Council (2008). Background Study for the Development Cooperation Forum: Trends in South-South and Triangular Development Cooperation. Retrieved February 1, 2011 from http://www.un.org/en/ecosoc/docs/pdfs/south-south_cooperation.pdf

G-77 (2003). Marrakech Declaration on South-South Cooperation. Retrieved January 15, 2011 from http://www.g77.org/marrakech/Marrakech-Declaration.htm

Griffith-Jones, S. & Ocampo, J. (2008). Sovereign Wealth Funds: A Developing Country Perspective. Columbia University. Retrieved January 5, 2011 from http://www.g24.org/sowf0308.pdf

Hammer, C. Kunzel, P. & Petrova, I. (2008). Sovereign Wealth Funds: Current Institutional and Operational Practices. International Monetary Fund: IMF Working Paper. (WP/08/254). November 2008. Retrieved January 10, 2011 from http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2008/wp08254.pdf

Lipsky, John (2008). Sovereign Wealth Funds: Their Role and Significance: Speech by John Lipsky, First Deputy Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund At the Seminar, Sovereign Funds: Responsibility with Our Future, organized by the Ministry of Finance of Chile Santiago, September 3, 2008. As Prepared for Delivery. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved January 10, 2011 from http://www.imf.org/external/np/speeches/2008/090308.htm

Magnus, George (2007). Sovereign Wealth Funds and the Rise of the Global South. The Globalist. Retrieved January 5, 2011 from http://www.theglobalist.com/storyid.aspx?StoryId=6419

The Economist (2008). The Invasion of the Sovereign-Wealth Funds: The Biggest Worry about Rich Arab and Asian States buying up Wall Street is the potential backlash. Leaders. Retrieved February 1, 2011 from http://www.economist.com/node/10533866?story_id=10533866

UNDP: United Nations Development Program (2009). Enhancing South-South Cooperation and Triangular Cooperation: Study of the Current Situation and Existing Good Practices in Policy, Institutions, and Operation of South-South and Triangular Cooperation. Special Unit for South-South Cooperation: New York, NY. Retrieved January 15, 2011 from http://southsouthconference.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/10/E_Book.pdf

UNDP: United Nations Development Program (n.d.). Buenos Aires Plan of Action. Special Unit for South-South Cooperation. Retrieved January 10, 2011 from http://ssc.undp.org/ss-policy/policy-instruments/buenos-aires-plan-of-action/#objectives

White, Ben (2005). Chinese Drop Bid to Buy U.S. Oil Firm. The Washington Post. Retrieved February 1, 2011 from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/08/02/AR2005080200404.html

Wilson, Simon (2008). Sovereign Wealth Funds: Wealth Funds Group Publishes 24-Point Voluntary Principles. IMF Survey Magazine: In the News. Retrieved February 1, 2011 from http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/survey/so/2008/new101508b.htm

Annex

Map 1: North-South Divide

The Brandt Line clearly shows the North-South Divide.

Source: www.pbs.org

Graph 1: November 2010 SWFs Around the Globe

Source: Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute

Table 1: Top 16 Sovereign Wealth Funds by Asset Management

| Country | Fund Name | Assets $Billion | Inception | Origin |

| UAE – Abu Dhabi | Abu Dhabi Investment Authority | $627 | 1976 | Oil |

| Norway | Government Pension Fund – Global | $512 | 1990 | Oil |

| Saudi Arabia | SAMA Foreign Holdings | $439.10 | n/a | Oil |

| China | SAFE Investment Company | $347.1** | 1997 | Non-Commodity |

| China | China Investment Corporation | $332.40 | 2007 | Non-Commodity |

| China – Hong Kong | Hong Kong Monetary Authority Investment Portfolio | $259.30 | 1993 | Non-Commodity |

| Singapore | Government of Singapore Investment Corporation | $247.50 | 1981 | Non-Commodity |

| Kuwait | Kuwait Investment Authority | $202.80 | 1953 | Oil |

| China | National Social Security Fund | $146.50 | 2000 | Non-commodity |

| Russia | National Welfare Fund | $142.5* | 2008 | Oil |

| Singapore | Temasek Holdings | $133 | 1974 | Non-Commodity |

| Qatar | Qatar Investment Authority | $85 | 2005 | Oil |

| Libya | Libyan Investment Authority | $70 | 2006 | Oil |

| Australia | Australian Future Fund | $67.20 | 2004 | Non-Commodity |

| Algeria | Revenue Regulation Fund | $56.70 | 2000 | Oil |

| UAE – Abu Dhabi | International Petroleum Investment Company | $48.20 | 1984 | Oil |

Source: Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute

—

Written by: Natasha Roberts

Written at: Geneva School of Diplomacy:

Written for: Professor Gyula Csurgai

Date written: February 15th, 2011

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- A Well-Intentioned Curse? Securitization, Climate Governance and Its Way Forward

- South Korea Is Not In Democratic Backslide (Yet)

- Weaponized Artificial Intelligence & Stagnation in the CCW: A North-South Divide

- Struggle and Success of Chinese Soft Power: The Case of China in South Asia

- Neoliberalism and the Sovereignty of the Global South

- Statehood in Modern International Community: Kosovo, South Ossetia, and Abkhazia