The launch of the Single European Currency marked one of the most ambitious steps forward in European integration. Though the euro is a symbolic driving force, it is built on the foundations of Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). This essay will posit that the euro has been a catalyst for integration within the EU, but that integration is further advanced in the economic realm than in others. Given the sheer scope this topic encompasses and the limited space available, the principal focus will be on the euro as a catalyst to integration via monetary union, and how though fiscal policy integration does not match its monetary equivalent, it has still been advanced by the euro-area financial crisis. Additionally the euro’s merits as a catalyst for integration via European identity-construction will be analysed, and noted throughout will be how the absence of political union equivalent to the levels of economic integration has been a source of structural difficulties and has compromised the full-integrative potential of EMU, and thus the euro.

The euro’s symbolism and attempts to foster European identity can be seen in its design. Its coinage links national symbols with European geography and ‘‘the symbol € [harks] back to classical times and the cradle of European civilisation. The symbol also refers to the first letter of the word “Europe”. The two parallel lines indicate the stability of the euro’’ (European Commission 2008). Additionally, two viable EMU models not featuring a single currency, such as keeping national currencies irrevocably fixed to national exchange rates or the introduction of a parallel common currency as suggested by the British, were rejected (Verdun 2010, p.326). A single currency was preferred for practical economic merits but also, arguably principally, because it was a politically attractive symbol of commitment to integration.

Clearly the euro acting as a symbol as much as a currency has been an important consideration. According to Kaelberer; ‘‘money is a purposeful political tool in the construction of identities’’ (2004, p.162). There were hopes that EMU would cause certain states to form a vanguard for political union, out of conviction and not just functional priority. Guy Verhofstadt called for the ‘‘ambition to develop a common social and economic policy in support of the euro’’, within his overall vision of seeing a core United States of Europe and outlying Organisation of European States (Dyson and Quaglia 2010a, p.775), and additional support came from Valery Giscard d’Estaing and Helmut Schmidt when they suggested in 2000 ‘‘that deeper political integration among euro-area members was the ‘only realistic option’ for ever-closer union’’ (Hodson 2009, p.517), and with Joschka Fischer’s encouragement in his 2000 Humboldt University speech that members of the euro-area be allowed to advance any plans for greater political and economic union (ibid. p.517-518). Indeed when Jacques Delors delivered his 1989 report on economic and monetary union, the text indicated that, ‘‘the completion of the single market will link national economies much more closely together and significantly increase the degree of economic integration within the Community’’ (Committee for the Study of Economic and Monetary Union 1989, p.10), yet it also clearly states that, ‘‘Even after attaining economic and monetary union, the Community would continue to consist of individual nations with differing economic, social, cultural and political characteristics’’ (ibid, p.13).

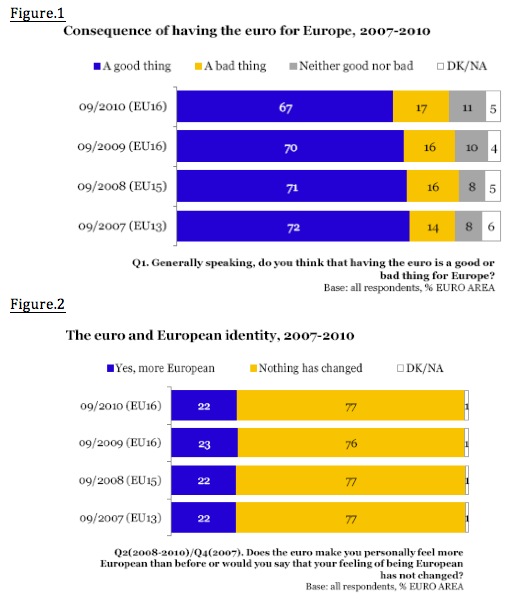

Nevertheless, there have been efforts to advance an integrationist agenda through the identity-fostering hopes of the euro, the support of political figures as noted above, or at treaty level, as demonstrated by the prominence of the euro in Declaration 52 of the Lisbon Treaty, which represented an endorsement of key symbolic elements of European political union, including the flag, anthem, motto and Europe Day (Dyson and Quaglia 2010a, p.761). Despite these efforts, events have developed more in line with the Delors Report’s prediction, for as Figure.1 (Eurobarometer 2010, p.9) demonstrates, though a majority in euro-area states feel that the euro has been positive, Figure.2 (ibid, p.10) clearly shows that the single currency has had little impact on increasing their sense of European identity.

Such findings support Kaelberer’s belief that, ‘‘Europeans do not have to love the euro, they merely have to believe that there are advantages to using it’’ (2004, p.173), and so while the euro’s merit as a catalyst for EU integration through identity-construction may not be as strong as its integrative effects in the economic realm, nor is it entirely deserving of dismissal.

Where the euro has evidently been a catalyst for integration is in EMU. The euro has, by necessity, created full monetary integration, and though economic governance remains under national controls the euro has facilitated some integration through the requirement of macroeconomic policy coordination. Regarding political integration within the EU, a measure has occurred as a result of this broader economic integration. According to Lord Howe, ‘‘the Single Market itself was always intended… to promote a degree of political unity’’ (1999, p.4). However it is important to distinguish political integration in the sense of enhanced cooperation and coordination – as has occurred in order to implement the smooth running of the euro-area, and in management of the single market such as competition policy, consumer protection and transport for example (ibid, p.5) – from the notion of moving towards a federalised entity, in which the euro has had little impact in comparison to specific and further reaching treaties, the ambitions of which have been tempered by the varying enthusiasms of member states in any event.

There are four pillars of EMU, namely a single monetary policy, a single monetary authority, a single currency and coordinated macro-economic policies (Verdun 2010, p.325). These are key institutional mechanisms for such a union and so bind the member states into the process. The euro is therefore based on a clear supranational monetary order under the European Central Bank, with the central banks of euro-area states effectively acting as branches through the European System of Central Banks. Further coordination – but not control – is provided by meetings of the Eurogroup, comprised of finance and economics ministers from euro-area members, typically occurring prior to these ministers’ Economic and Financial Affairs Council (ECOFIN) meetings (ibid, p.326). While the Eurogroup has gained greater prominence during the euro-area crisis, its power and influence is still relatively limited, since, despite rebuffed attempts at asserting external influence on it by the likes of Nicolas Sarkozy (Dinan 2010, p.410), the ECB ultimately exercises full sovereignty in conducting a single euro-area monetary policy, and so the euro has undoubtedly been a catalyst to integration in monetary terms.

However, while the asymmetry between such supranational monetary governance and national fiscal policy control is problematic, this is only compounded by the absence of a centralised, decision-making political union. This is best highlighted in Article 3 on the Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union (amended by the Lisbon Treaty), under which monetary union encompassed differentiated integration – therefore applying to euro-area members – and was also the exclusive competence of the EU – thus including non euro-area states as well (Dyson and Quaglia 2010b, p.2). Such a scenario was pregnant with legal confusion as ‘‘European macro-economic governance comprised a mixture of ‘exclusive’, ‘shared’, ‘coordinating’, and ‘complimentary or supporting’ competences’’ (ibid. p.2) and demonstrated how the euro has been as much a generator of potential structural confusion as of integration.

Such a situation is in-keeping with certain aspects of European integration theory. Intergovernmental theory essentially posits that nation states remain in control of the integration process (Cini 2010, p.87), as evidenced by the fiscal sovereignty of members and those states that have opted out of the euro. Yet Neo-functionalism also has a part to play, principally the spillover concept and its functional, political and cultivated forms (Jensen 2010, p.76). Political and cultivated spillover respectively refer to when various actors attempt to argue for European-level solutions to problems, and when supranational actors push for greater integration. Functional spill-over, whereby one area of cooperation functionally leads to another, is the most relevant regarding the euro as a catalyst for integration. A prime example is how by the late 1980’s core European states essentially made up an Optimal Currency Area in the Deutschmark zone and aligned their monetary policies with the Bundesbank, thus making the establishment of the euro a seemingly logical functional step to encourage prosperity (Verdun 2004, p.87).

Indeed Frankel and Rose suggest that with monetary integration, the euro-area may become an OCA, even if it was not one before, since ‘‘monetary union itself may lead to a boost to trade integration and hence business cycle symmetry’’ (1998, p.1010). This ‘endogeneity of OCA’ effect sees the euro setting in motion, or strengthening, forces conductive to integration within the EU in such areas as trade, labour mobility and similarity of shocks and cycles (ibid, p.1011). Enderlein however believes that ‘‘EMU is not an optimal currency area (i.e. the euro-area is characterized by a considerable heterogeneity of the fundamental economic variables). The ECB’s single interest rate is therefore likely to translate into country-specific effects generating higher or lower growth rates’’ (2006, p.1138). Due to the disparities of the ‘one size fits all’ monetary policy, there have admittedly been cyclical divergences under the euro rather than broad convergence, especially between ‘core’ and ‘peripheral’ euro-area countries. For example, Ireland boomed in the mid-2000’s while Germany lagged, but as the economic climate has swung the German economic eagle soars while the head of the Celtic Tiger is mounted on a wall, stalked and felled by a collapsed property-bubble and huge debts.

Before the crisis that precipitated such a situation, the level of integration in the fiscal policies of euro-area members still fell, and largely remains, comparatively far behind that of monetary union. According to Wolf, even during the early debates following the 1970 Werner Report, core European states preferred either ‘Locomotive’ or ‘Coronation’ strategies, with the former advocating ‘‘the transfer of only some… competences for monetary policy to a new central bank but to retain most of the economic competences… on national level’’ prior to introducing a common currency, with the latter essentially advocating the opposite (2002, p.45). Decades later it appears the ‘Locomotive’ camp have won the argument.

Nevertheless, the fact that enhanced macroeconomic policy coordination has been necessary, even in good times, demonstrates how the single currency has acted as a catalyst for integration. In the Treaty on European Union, Article 102a laid put the principles by which EU members were to conduct economic policy, and Article 103 highlighted the central role of the Broad Economic Policy Guidelines (BEPGs) as the basis for closer coordination (Dyson and Quaglia 2010b, p.699). Additionally, the Stability and Growth Pact stipulated that euro-area members adhere to a 3% deficit limit and 60% public debt limit in order to ensure fiscal responsibility prior to and after joining the euro, and involves multilateral budgetary surveillance, a ‘preventative’ or early-warning mechanism and the excessive deficit procedure, a ‘corrective’ mechanism that could potentially yield fines (Hallerberg and Bridwell 2008, p.71-72). Though such stipulations have been temporarily relaxed in the wake of the financial crisis, the SGP ensured that, though members retained fiscal sovereignty, they were still compelled to follow integrative guidelines conductive to euro-area stability. Indeed, following the euro’s introduction euro-area members saw average budget deficits drop to 0.60% for 1999-2006 from the 3.9% levels of 1991-1998 (ibid, p.69).

The principal issue remains that the euro catalysed monetary integration far more than fiscal. Such asymmetry, combined with the absence of a streamlined political union, can entail weakness on the EU’s part to implement swift, unified action to manage internal crises. As the financial crisis commenced many countries charted their own courses, with some guaranteeing bank deposits, bonds and debts, while others outright nationalised theirs, both actions arguably contributing to or exacerbating the sovereign debt crises that some were undergoing (Featherstone 2011, p.201). The Maastricht Treaty had not provided for exceptional crisis-management and so the system was ill-equipped to deal with the crisis, ‘‘lacking the capacity for speedy reaction, policy discretion and centralised action’’, as demonstrated by the Eurogroup and ECOFIN meetings on 6-7 October failing to agree action and settling for a broad declaration, though the Paris summit of October 12th attempted a more coordinated response (ibid, p.201).

The crisis facilitated far greater inclination towards European fiscal policy coordination, and it can even be argued that those countries that have received bailouts have effectively surrendered fiscal sovereignty to the EU in exchange for being ‘saved’, vicariously causing the euro to have an integrative effect since stronger members have facilitated bailouts in order to maintain euro-area stability and thus their own. Indeed the crisis has not yet subsided, with Portugal’s recent bailout request adding a third confirmed letter to the so-called PIIGS (Cendrowicz 2011), and indications from Wolfgang Schäuble that Greece may face sovereign debt-restructuring (Aldrick 2011), with any prospective defaulting having dramatic consequences for the euro-area, including likely recapitalisations (Warner 2011).

Ultimately, though macroeconomic policy coordination has always existed in parallel with monetary union, the requirements of the euro-area crisis has meant that (arguably conforming to political and cultivated spillover types) at best there has been a heightened call for increased fiscal policy coordination and even new institutional mechanisms such as a ‘European Debt Agency’ (Featherstone 2011, p.210), and at worst some countries have effectively transferred fiscal oversight to the EU, as demonstrated by regular scrutinising visits to Greece by teams from the EU Commission, ECB and IMF (ibid, p.206-207). In either scenario, intent to shield the euro has been a catalyst to further, albeit far from complete fiscal policy integration within the EU and especially between euro-area members.

Barring unforeseen events the levels of integration achieved through the single currency thus far are virtually guaranteed. Withdrawal from the euro is in principle possible according to the German Federal Constitutional Court (Dyson and Quaglia 2010b, p.3), but in reality exiting would be too costly technically, economically and politically. While withdrawal may hold attraction for debt-ridden countries, just as prosperous states may benefit in expunging weaker members, no mechanism exists to facilitate this. The reality is that monetary union was created without the umbrella of political union or full economic governance, and it would seem that calls for the latter (which, if implemented, some argue would vicariously lead to the former) have grown louder to address this. However, as Andre Sapir told the European Commission in 2009, ‘‘there is now a distinct possibility that this crisis will be remembered as the occasion when Europe irretrievably lost ground, both economically and politically. Although Europe should be part of the answer to current economic woes, there is currently no appetite for bold European initiatives’’ (ibid, p.1).

In conclusion the Single European Currency, by design and recent accident, has indeed been a catalyst to integration within the EU, but with the caveat that this integration is unevenly distributed. The euro is monetary union and so is naturally further reaching here than in fiscal, identity and especially political integration. This structure was institutionally enshrined in Maastricht and discussions during subsequent treaty summits on potential reforms to the eurosystem have been subject to deliberate procrastination – such as the preference of the Working Group on Economic Governance to maintain the EMU status quo in its 2002 report (Hodson 2009, p.520) – despite the hopes of some that functional, political and cultivated spillover would facilitate the gradual advance of ‘ever closer union’. As a result the euro and EMU in general are compromised from reaching their full integration potential, yet given the scope and penetration of the euro it has the capacity to cause incredible damage should it fail and so, even if there are disparities in broader levels of integration, the determination to avoid such an outcome has unified the EU’s euro-area members and non-members alike as no time before.

Bibliography

Aldrick, P. 2011. Fears grow over Greek debt default despite bail-out [Online]. Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/economics/gilts/8452070/Fears-grow-over-Greek-debt-default-despite-bail-out.html [Accessed: 15th April 2011]

Cendrowicz, L. 2011. Already Hurting, Portugal Must Cut Deeper for a Bailout [Online]. Available at: http://www.time.com/time/business/article/0,8599,2064243,00.html [Accessed: April 11th 2011]

Cini, M. 2010. Intergovernmentalism. In: Cini, M. & N. Pérez-Solórzano Borragán. European Union politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 86-103

Committee for the Study of Economic and Monetary Union (No Author). 1989. Report on economic and monetary union in the European Community [Online]. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/publication6161_en.pdf [Accessed: 1st April 2011]

Dinan, D. 2010. Ever closer union : an introduction to European integration. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dyson, K and Quaglia, L. 2010a. European Economic Governance and Policies – Volume I: Commentary on Key Historical and Institutional Documents. Oxford: OUP

Dyson, K and Quaglia, L. 2010b. European Economic Governance and Policies – Volume II: Commentary on Key Policy Documents. Oxford: OUP

Enderlein, H. 2006. The euro and political union: do economic spillovers from monetary integration affect the legitimacy of EMU? Journal of European Public Policy 13(7), pp. 1133-1146

Eurobarometer (No Author). 2010. The euro area, 2010 – Public attitudes and perceptions – Analytical report [Online]. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/flash/fl_306_en.pdf [Accessed: 1st April 2011]

European Commission (No Author). 2008. The euro, our currency [Online]. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/events/2009/theeuro/isola3_en2008-2009.pdf [Accessed: 7th April 2011]

Featherstone, K. 2011. The Greek Sovereign Debt Crisis and EMU: A Failing State in a Skewed Regime. Journal of Common Market Studies 49(2), pp. 193-217

Frankel J and Rose, A. 1998. The Endogeneity of the Optimum Currency Area Criteria. The Economic Journal 108 (July), pp. 1009-1025

Hallerberg, M and Bridwell, J. 2008. Fiscal Policy Coordination and Discipline: The Stability and Growth Pact and Domestic Fiscal Regimes. In: Dyson, K. H. F. 2008. The euro at 10 : Europeanization, power, and convergence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 69-86

Hodson, D. 2009. EMU and political union: what, if anything, have we learned from the euro’s first decade? Journal of European Public Policy, 16(4), pp. 508-526

Jensen, C.S. 2010. Neo-functionalism. In: Cini, M. & N. Pérez-Solórzano Borragán. European Union politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 71-85

Kaelberer, M. 2004. The euro and European identity: symbols, power and the politics of European monetary union. Review of International Studies 30, pp. 161–178

Lord Howe of Aberavon. 1999. Europe: single market or political union? Economic Affairs 19(4), pp.4-9

Verdun, A. 2004. The Euro and the European Central Bank. In: Cowles, M. G. & Dinan, D. Developments in the European Union 2. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 85-99

Verdun, A. 2010 – Economic and Monetary Union. In: Cini, M. & N. Pérez-Solórzano Borragán. European Union politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 324-339

Warner, J. 2011. What Europe’s coming debt default will look like [Online]. Available at: http://blogs.telegraph.co.uk/finance/jeremywarner/100010020/what-europes-coming-debt-default-will-look-like/ [Accessed: 15th April 2011]

Wolf, D. 2002 ‘Neofunctionalism and intergovernmentalism amalgamated: the case of EMU’. In: Verdun, A (ed.), The Euro: European Integration Theory and Economic and Monetary Union. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 29–49.

(Note: this paper was researched and written during March/April of 2011, and so is a product of its time. In the coming months or even years the crisis in the euro-area may accelerate or abate and result in changes unforeseen by this paper, ranging from greater integration to partial or even complete collapse. Of course many specialists in this field do not predict the latter, but then most maritime experts didn’t foresee the Titanic sinking either)

—

Written by: Iwan Benneyworth

Written at: Cardiff University

Written for: Professor Kenneth Dyson

Date written: April 2011

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Integrating under Threat: A Balance-of-threat Account of European Integration

- EU Migration Policy: The EU as a Questionable Actor and a Realist Power

- Hungary’s Democratic Backsliding as a Threat to EU Normative Power

- How Does the EU Exercise Its Power Through Trade?

- Is the European Union’s Institutional Architecture in Multiple Crisis?

- Conceptualising Europe’s Market Power: EU Geostrategic Goals Through Economic Means