To what extent, if any, has democratisation in Northern Ireland and the Spanish Basque Country contributed to the end of political violence?

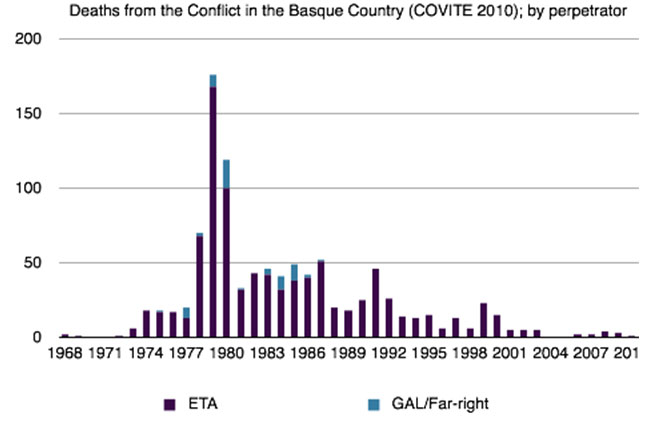

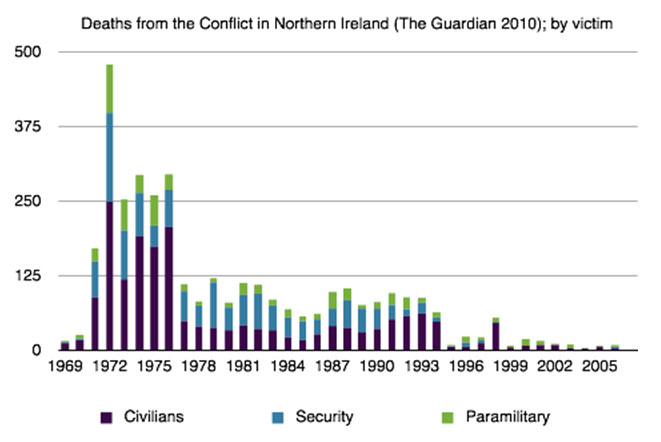

“Whereas most of Western Europe has enjoyed considerable peace and stability since the end of World War II, the Basque Country and Northern Ireland have suffered from protracted political unrest” (Irvin and Rae 2001, p.77), regarded as anachronisms in contemporary Europe and viewed with bewilderment by outside observers (Keating, p.181). Nowadays, the violence has undergone a radical deescalation (see Appendix I). Simultaneously, both societies have undergone a democratic transition (albeit to different degrees), to the point that they are now unanimously considered to be fully-fledged local democracies, with their own autonomous representative assemblies with legislative powers, and where citizens have the same rights and duties as expected in any other established democracy. This dissertation will try to determine the impact of this democratisation in helping bring down terrorism, by ultimately reaching a democratic compromise between all parties (like in Northern Ireland), or by delegitimising terrorist groups’ goals and means in the eyes of their audience (such as in the Basque Country). In order to do that though, one first needs to understand what democratisation has actually entailed. More particularly, this study will look at the impact of devolution and the role of the two representative assemblies, the Basque Parliament and the Northern Irish Assembly, within the wider democratisation and “peace process”.

This dissertation will answer the question through close analysis of the democratisation processes themselves, and the agreements reached. Furthermore, the discussion will necessitate a very close look at ETA and the IRA, and their respective political movements, their initial ideology and their transformation, and acceptance or rejection of the ongoing domestic processes. It is crucial to understand how their formation reacted to a particular domestic situation, and their place within their wider nationalist movements. More specifically, this analysis will trace their ideological development and increased radicalisation, to determine how ideologically compatible they were to the process of democratisation, and how these groups reacted to, or shaped, it. Ultimately, this dissertation will address whether democratisation happened because of the activities of these organisations, or despite of it. In analysing specific perpetrators of political violence, this dissertation will largely focus on the main actors (ETA and the Provisional IRA) because it is to their actions and formation that opposing groups reacted; e.g., the PIRA was responsible for half of Northern Irish killings, while the rest was divided among a wide array of groupings (Cronin 2009, p.43). Furthermore, there is significant ideological similarity between the two groupings, and their historical emergence shows similar patterns. While the existing ETA and the remnants of the IRA are irrefutably terrorist groups, whether they can be classified as such for their entire existence is up to debate. Definitionally, this argument relies on a particular understanding of the concepts that are key to the scope of this study, “democracy” and “terrorism”. This dissertation will use a definition that makes the existence of democracy a conditionality for the use of the term “terrorism”.

While not embracing positivism, this dissertation will when possible use a quantitative approach, which allows for a clearer comparison between the two cases. For example, to objectively measure the levels of terrorism and the intensity of political violence, this study will look at death figures. Of course, terrorism goes beyond the mere killing of people, but the use of numbers simplifies the analysis. Moreover, the definition that this essay will use contains a ‘checklist’ to determine whether the conditionality of democratisation, has been achieved. In order to measure popular support for a certain political option, such as Irish or Basque nationalism, electoral results will be used as a regular, objective and quantifiable measure.

Basque and Irish nationalists have often appealed to one another to legitimise their own “struggle”, and in turn justifying a certain policy. For example, radical Basque nationalists have at various stages practiced the Irish policy of ‘abstentionism’ in Basque and and Spanish institutions (El Pais 1981), deeming them illegitimate. However, ultimately these problems are the result of local processes, and while this is a comparative study, the analysis will focus on the domestic impact of democratisation, not necessarily trying to find world historical patterns. Ultimately, the two cases can only be viewed within their own domestic context, and the solution for one does not necessarily set precedent for the other. In the end, this study will demonstrate that there is no single answer answer to the question and that democratisation does not necessary bring down terrorism. In Northern Ireland, the Provisional IRA, and the other actors, accepted the reality and necessity of the democratic process, and decided to contribute by calling off their “campaign” and declaring a ceasefire. In the Basque Country, ETA’s unwillingness to accept the legitimacy of the democratic processes led to an increase in their terrorism, further alienating their audience and increasingly diminishing their support in the eyes of their audience. In the end, while in Northern Ireland the Belfast Agreement was largely successful in ending the violence, the advent of democracy in Spain was merely a catalyst for ETA’s renewed “campaign” and an increase in their terrorist actions.

Definitions: Terrorism, Political Violence, Democracy

Defining the term ‘terrorism’ is necessary before one even begins to write about the subject. The lack of a universally accepted definition makes it a flexible term, and a different understanding of the meaning of these terms can give a different answer a question. The negative connotations associated with the term have made it into a delegitimising tool for states, who have ensured that the few international definitions exclude the possibility of state terrorism. Under these state-drafted definitions, the perpetrator is always explicitly a non-state actor, while the victims are state infrastructure and civilians: ‘state terrorism’ is therefore a contradiction (Turk 2004, p.272). This dissertation will argue that while political terrorism is violent, not all political violence is terrorist.

Democracy and terrorism are sometimes considered to be rival opposites. A terrorist fights democracy, and democracies fight terrorism. This is why in principle, “democracies do not negotiate with terrorists” (Cronin 2009, p.35). Democracy is used, inversely to “terrorism”, as a legitimising tool; while terrorism is a “bad thing”, democracy is a “good thing”. This unanimity means that the term can be used to justify certain policies. To use George W. Bush’s rhetoric, Iraq and Afghanistan were “terrorist” regimes, that have now been replaced by “democracies” (Turk 2004, p.281). The flexibility of these two terms means that a different understanding of their meaning results in a completely different understanding of the situation. Therefore it is crucial to determine, before one attempts to answer the question, what one understands these terms to mean. This study shall be using a definition that manages to define both “democracy” and “terrorism” within a sentence, and which applies perfectly to the scope of this study. It was compiled by Irish writer and journalist Paddy Woodworth, in the context of studying the ETA and GAL (the Spanish government’s anti-ETA death squads in the 1980s). Under many mainstream definitions, the GAL would fail to be classified as terrorist, therefore Woodworth had to find a definition that encompassed both ETA and the GAL. Furthermore, his writing on Spain inevitably draws upon his Irish experience, making his definition perfect for this comparative study. Ultimately, he defined terrorism as “the use of violence for political ends, in a situation where the essential democratic liberties – the freedoms of speech, association and representation – are in operation” (Woodsworth 2001, p.9). This definition succeeds where many have failed; it establishes a conditionality, “democracy”, under which political violence can be classified as terrorist. It defines the criteria for this conditionality to be achieved, and in this sense it is quite methodical and scientific. Moreover, this dissertation’s definition of choice diverges from many others by not specifying who the perpetrators or the victims are, and in this sense it is much less exclusive. It defines terrorism not as a tactic, but as a category of political violence (Turk 2004, p.273), that can be used when democratic circumstances are present; therefore the violence is illegitimate. On the other hand, political violence on its own can be “an understandable response to oppression and exploitation” (Turk 2004, p.273). Northern Ireland, but to some extent also the Basque Country, are divided societies and it is usually understood that the political violence is a result of these societal divisions: nationalists versus unionists, centralism versus independence, etc. David E. Apter however argues that political violence in fact reinforces these divisions, “polarising them around affiliations of race, ethnicity, religion, language, class” (Apter 1997, p.1). If political violence responds to legitimate concerns, and therefore is not terrorist, the use of violence itself may force people to identify with either camp, and in fact may worsen the situation. This dissertation will look very closely at those three democratic conditionalities to determine at what point the two societies achieved democratisation, and therefore at what point political violence became terrorism.

The International Context: The New Left Wave

This section will address why these two cases simply do not fit within a European pattern of terrorism, and why out of all the groups that emerged in the 1960s, those in the Basque Country and Northern Ireland are those that are still present in our recent memory. ETA and the IRA are two examples that provide an interesting challenge to David C. Rapoport’s theory on the “Four Waves of Terrorism”. Using his timeline, ETA and the Provisional IRA can only possibly be classed under the third, or ‘New Left’, wave of terrorism of the 1960s (Rapoport 2004, p.56). The other European ‘New Left’ groups, such as the German RAF, French Action Directe, and the Italian ‘Brigate Rosse’, easily demonstrate a pattern: they were all established within a decade of each other (between 1967 and 1977), founded on Marxist principles, and “came to regard themselves as […] the radical residue of the ‘generation of 68’” (Apter 1997, p.19). Despite significant later borrowing of New Left ideology, ETA and the PIRA were born out of older political traditions that predate this so-called “wave”, and therefore are difficultly grouped with those others. Furthermore, they outlived the others by at least two decades; Rapoport acknowledges that “occasionally an organisation survives its original wave” (2004, p.48) and adapts, but that does not necessarily prove Rapoport’s belief that ETA and the IRA are part of the ‘third wave’. The reason why the ‘New Left’ groups vanished within a decade, and the ones scope of this study lingered for much longer, is simply the lack of historical and popular legitimacy of the former. Their emergence responded to a specific ideological phase in Europe and is a “classic tale of betrayal” (Apter 1997, p.19); when the phase ended and lost political relevance, these terrorist groups disappeared as quickly as they had emerged. On the other hand, the ‘Provos’ and ETA are offsprings of much older traditions, Irish republicanism and Basque nationalism respectively, and are two of the longest-living terrorist organisations in world history (Cronin 2009, p.221). While not wanting to dismiss Rapoport’s analysis completely, there is certainly an “excessive internationalism” (Rapoport 2004, p.56) when it comes to ETA and the IRA, and they are often forcibly grouped with many others in an attempt to find nicely-fitting historical patterns of terrorism (Loughlin 2003).

Non-democracy: Before ETA and the Provisional IRA

The word “democratisation” entails a transition from a non-democratic society into a democratic one. Using Woodworth’s three democratic conditions, freedoms of speech, association, and representation, (Woodworth 2005, p.9), this section will determine whether at the birth of ETA in 1959 and the PIRA in 1969, the Basque Country and Northern Ireland were democratic societies.

For the Basque Country, the answer requires little exploration. Franco’s dictatorship in Spain outlawed any opposition parties, public opinion was heavily monitored, and elections were simply non-existent. But particularly for Basques, who saw the Spanish state as “foreign” (García de Cortázar 2005, p. 119), the repression was even worse, with the use of the Basque language punished and any sign of nationalist sentiment crushed. The Francoist repression and the lack of even an illusion of democracy was “a requisite for ETA’s violence” (García de Cortázar 2005, p.118). As “agents close to the state often retaliated with violence, [this] further undermined the legitimacy of the state” (Loughlin 2003, p.4).

For Northern Ireland however, the question requires further analysis. As an integral part of the United Kingdom, Northern Irish citizens voted for elections to the United Kingdom parliament in their own constituencies, and legally enjoyed the same rights and duties as citizens in other parts of the country. In addition, Northern Ireland enjoyed wide-ranging autonomy in the form of an elected the Northern Irish Parliament. On paper, the answer would obviously be yes. Unfortunately, the reality of the situation in Northern Ireland demonstrated an extreme case of “tyranny of the majority”. The entrenched Protestant political power, tolerated by Westminster (Coogan 1987, p.440), ensured that the three ‘democratic conditions’ were non-existent for the large Catholic minority, and it was the illusion of democracy created by regular elections that legitimised the status-quo for so long. But let it be clarified that despite the labels, Catholic and Protestant, the following conflict would be about political and economic conditions, and not about “the correct way to worship a Christian god” (Bloomfield 1997, p.11).

‘Representation’, ‘Speech’, Association’

Tim Pat Coogan’s “The IRA” provides us with a depressingly true account of simply how undemocratic the situation was in Northern Ireland (1987, p.433-448). Despite the Northern Irish Parliament (i.e. ‘Stormont’) being an elected assembly, the majoritarian First Past the Post (FPTP) electoral system, combined with the indiscriminate redrawing of boundaries (e.g. ‘gerrymandering’) ensured that a Unionist candidate was elected even in areas with Catholic majorities. For example; “Derry city, which had 36,049 Catholics and 17,695 Protestants, was carved up so that it returned a Unionist.” (Coogan 1987, p.443). Most significantly, this was also the case in local authorities who were in charge of many public services; “in Derry […] the Unionists managed so to arrange matters that their 9,325 electors returned twelve representatives whereas the 14,325 Nationalists could only return eight members” (Coogan 1987, p.443). Governance was not only unrepresentative and undemocratic, but it had very significant social consequences, most importantly in “housing, welfare, education, and employment” (Cronin 2009, p.42, 43): in Dungannon (53 per cent Catholic), “a housing survey […] discovered that between 1945 and 1968 the allocation of new houses to Protestants and Catholics […] was Protestants 71 per cent, Catholics 29 per cent.” (Coogan 1987, p.444). Equal representation was simply non-existent. Unionist control of Stormont and most local authorities allowed them to pass laws that benefited the Protestant community and cracked down on any non-British (i.e. pro-Irish) sentiment. “The Flags and Emblems (Display) Act (Northern Ireland) 1954 ‘gives special protection to […] who wishes to display a Union Jack. […] Failure to remove [other] emblems on police request constitutes an offence’. (Coogan 1987, p. 441). In practice, this meant that the Irish Tri-Colour could be considered a ‘breach of the peace’, while the Union Jack had to be treated with respect (as a representative of supremacy and justice). Nationalist and civil rights marches were continuously outlawed and cracked down upon, ultimately leading to events such as ‘Bloody Sunday’. On the other hand, “despite warnings that it could lead to a bloodbath”, Loyalist hate-inciting marches like the ‘Apprentice Boys of Derry’ March were allowed and encouraged (Coogan 1987, p.423). By any definition of the term, Northern Ireland was an undemocratic society at the emergence of the Provisionals. Therefore, according to this dissertation’s definition of choice, political violence emerging within these domestic contexts can not be deemed as terrorist. In the next section, this analysis will explore the situation that triggered the formation of the armed groups that sought to reverse that situation: ETA and the Provisional IRA.

The Emergence of ETA and the ‘Provos’:

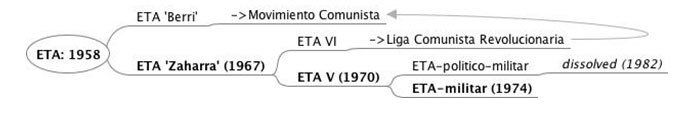

ETA: 1958-1974

Historically, Basque nationalism had been deeply Catholic and conservative; the movement was dominated by the party created by the Basque Nationality Party (PNV). In 1958, a group disillusioned with the PNV’s excessive religiosity and its perceived conformity with the regime split off from its youth organisation. Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (Basque Homeland and Freedom) was born as an organisation defined by “Basque patriotism, democracy, and aconfessionality” (García de Cortázar 2005, p. 121). By its First Assembly in 1962 ETA was declared a “Basque Movement of National Liberation” (ABC 2010) that recognised: the ‘Basque language’ replacing the ‘Basque ethnicity’ as key element in defining nationality; religious “aconfessionality”, explicitly rejecting the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, while accepting its social doctrine; ideological “anti-communism”, while still valuing it as a method of action; the independence of ‘Euskadi’ (the Basque Country), compatible with European federalism (PNV 1995). During its first decade of existence, this new organisation focused its efforts on social initiatives, while occasionally performing sabotage actions against the regime’s infrastructure. Seen as the only Basque resistance force in the Basque country, it claimed significant popular support and funding, even amongst sections of the clergy, frustrated with the PNV’s inaction (García de Cortázar 2005, p. 126).

By the mid-1960s, ETA took a clear ideological turn to Marxism, inspired by left-wing anti-colonial rhetoric, accepting the ‘principles of revolutionary war’ (García de Cortázar 2005, p.121), signalling the real birth of the abertzale movement, e.g. radical left-wing Basque nationalism. In 1968, inspired by the momentum of European New Left protests (ABC 2010) ETA decided to start this “revolutionary war” by killing a police officer in its first ever assassination. Its influence and political support was rising and had reached its peak by the time of the second assassination, that of Carrero Blanco, Franco’s Prime Minister, in 1973, in what is to date the most high-profile successful assassination by the organisation. The organisation was seen as an anti-authoritarian force, receiving increased media and international publicity, while the French government even tolerated the use of their territory as a ‘safe haven’ from which to operate (Irvin and Rae 2001, p.77). In september 1974, an indiscriminate ETA bombing that killed 13 civilians caused a major split within the organisation, between those who believed in the primacy of military action, ETA(military), and those who believed military action ultimately had to be subordinate to political and mass efforts, ETA(political-military) (Fernandez Soldevilla 2007, p.4). Earlier splits had seen the more more Marxist and less Nationalist factions of ETA splinter off to ultimately join Spain-wide radical left-wing political parties, but none was as historically significant as this one (see Appendix II). In 1974, at the brink of the transition to democracy there were two rival ETA’s, with different strategies but ultimately the same goal.

It is crucial to understand the ideological development of ETA during the Dictatorship. The increased protagonism of ETA demanded a clear plan of action, but it was always the “unstable equilibrium between socialism and radical nationalism”, and the “coordination between the armed and the political struggle” (Fernandez Sodevilla 2007, p. 3) that caused every rift within ETA. The continued scissions of the more politically-oriented faction left ETA to become increasingly radicalised, while it was the more military-prone factions that remained; “when military and political logics collide, […] the ‘armed wing’ will impose its law” (Woodworth 2001, p. 40). As will be demonstrated later on, it is this continued radicalisation and militarisation of ETA, and its gradual transformation from an all-encompassing “Basque National Liberation Movement” into an indiscriminate self-defined ‘military’ organisation, that ultimately affected its willingness to engage with the future democratic process and the newly-created democratic institutions.

The Provisional IRA

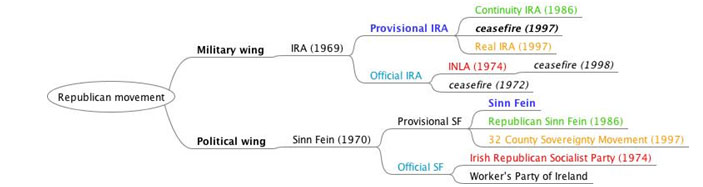

Parallel to the abertzale movement, there was the Republican movement in Northern Ireland, represented by the IRA at the military level and Sinn Féin at the political level. Historically, it amalgamated members from both sides of the political spectrum, while maintaining a traditional legitimist and abstentionist position towards the Irish Dail, Northern Irish Parliament, and the British Parliament. The failure of the IRA’s ‘Border Campaign’ of 1956-1962 against Northern Irish targets demanded a clear shift in strategy. The leadership of the Republican movement then took a significant turn to the left, turning to Marxism to explain the divisions within Northern Irish society (Hanley and Millar 2010, p.458). Slowly, the more socialist and political outlook was overtaking the traditional military approach within the Movement. This angered the more conservative factions, who saw it as a betrayal of Republican tradition, and was also to the discontent of the Northern Irish Catholic communities, who had seen the IRA as their traditional protectors. The IRA had been “blackened, almost unarmed, and certainly very largely discredited” (Coogan 1987, p. 433), and its acronym began to mean ‘I Ran Away’ (Hanley and Millar 2010, p.458). The Civil Rights movement of the late 1960s (Loughlin 2003, p.43) demanded a clear response by the Republican Movement, and ultimately the divisions between the two factions led to a major split.

The IRA had historically rejected the legitimacy of the post-partition States in the Island, and sought to overthrow the two with a 32-County Republic. By 1969 however, the leadership of the Movement was debating whether to end abstentionism and engage with the existing institutions, seeking to promote reunification and Civil Rights through political rather than military means (which were seen as only entrenching sectarian divisions). This led to a major split within the IRA in 1969, between the more legitimist “Provisionals” (PIRA) and the socialist “Officials” (OIRA), corresponded by an identical split in Sinn Féin in 1970 (see Appendix II). The “Provisional” camp inherited most of the IRA’s infrastructure and leadership, and started a high-intensity campaign during The Troubles against the British State and Loyalist paramilitaries, one that would last for 30 years. Sinn Féin, the political instrument of the PIRA, only became successful when the “Provos” called their ceasefire. The fate of the “Official” camp would, on the other hand, be short-lived. It made little sense for the more politically-oriented to still have a military wing; the OIRA called a permanent ceasefire in 1972, while Official Sinn Féin ultimately rejected its former links and fully embraced Marxism, renamed itself “The Worker’s Party” but failed to garner any significant support (Hanley and Millar 2010, p.457). From now on, only the Provisional camp had the means to represent the Republican Movement. Mirroring the first two ETA splits, the Official/Provisional split saw the more Marxist and politically-oriented factions split off (see Appendix II), with little success, while the more nationalist and militaristic factions stayed on and claimed the historical legacy of the organisation.

Basque Democratisation: 1974-1982

By the time of Franco’s death in 1975, and the impending democratic transition that followed, there existed two groups claiming the ETA legacy, which had drifted into different political positions. While ETA(pm) was the largest of the two, and inherited most of its members and leaders, ETA(m) was left with most of the weapons and money. The urgency of this transition demanded of the abertzale left, in its many and fragmented political and military forms, to coordinate efforts and determine a plan of action. Created by ETA(pm), and initially supported by ETA(m), came to life Koordinadora Abertzale Sozialista (KAS), an umbrella group formed of military groups, political parties, trade unions, that had a more-or-less shared view for Euskadi’s future (Fernandez Soldevilla 2007, p. 12). Its task was to prepare a coordinated plan for the impending 1977 Spanish elections, the first in four decades.

Ultimately, KAS transformed itself into the Euskadiko Ezkerra (EE, Basque Left) electoral coalition, which ETA(pm) supported, while ETA(m) ended up rejecting the entire process and calling for abstention. Somewhat surprisingly, the results of this first democratic challenge in 1977 demonstrated that the abertzale movement had overestimated its popularity. Euskadiko Ezkerra (ETA(pm)’s project) obtained a discrete 6.08% of Basque votes, translated into one MP, while other leftist Basque nationalist forces achieved only a combined 4.21% of the vote. But for ETA(m), it was a complete disaster, as its call for abstention was ignored and Basque turnout was roughly in line than the Spanish average. (Basque Government 2011). The result of these elections is crucial to understand for the future political development of the two wings of the abertzale left. ETA(pm) would accept the reality of the democratic process, and would claim in the aftermath of the 1977 elections: “if earlier, legitimacy was based exclusively on force, nowadays this legitimacy comes from popular vote” (Fernandez Soldevilla 2007, p. 25). ETA(m), on the other hand, having failed at its objective to have the entire process delegitimised, created in 1978 a rival electoral coalition to EE to promote its political thesis: Herri Batasuna (HB).

Euskadiko Ezkerra slowly detached itself from its ETA origins and begun to form part of the consensus amongst all parts of the (elected) Basque political spectrum for the need for Basque autonomy. In the Basque Country, “it was impossible to talk about democracy without talking at the same time about self-government” (Mees 2003, p.34), and autonomy was a foreseen result of the transition to democracy. While not calling off its armed campaign, ETA(pm) continuously increased its political focus, while ETA(m) parallelly further increased its “military” focus for which the 1977 elections were only a trigger (see Appendix I). Between 1978 and 1980, the years between the first Spanish elections and the approval of the Basque Statute of Autonomy, ETA(m) demonstrated its rejection of the entire democratic process by killing a total of 234 (Ministry of Interior 2010) to 336 (COVITE 2010); 1980 being “the year of permanent disgrace for the Basque Country” (García de Cortázar 2005, p.141). The “years of lead” of 1978-1980 claimed around a third of total ETA victims to date.

Despite the increased political involvement and relative moderation of ETA(pm), the results of the 1979 elections, the first where EE and HB first came to face, demonstrated that the popularity of ETA(m) had quickly overtaken that of its rival. Herri Batasuna, with 15.02% of votes and 3 MPs, obtained almost twice as many votes as EE’s slightly increased 8.04% and 1 MP (Basque Government 2011). Two significant conclusions may be drawn from these electoral results, which occurred in the midst of the single deadliest year in Spain’s history. Within the abertzale movement, the military thesis, represented by a party that rejected the very same institutions it was elected to, had become more popular than its more politically-oriented counterpart. But perhaps more importantly, these results showed a massive increase in the popularity of the the abertzale movement, which obtained nearly a quarter of total votes (Basque Government 2011).

“Guernica”

A few months after the first post-constitutional elections of 1979, the consensus for Basque Autonomy came to reality. The parties that had formed the “pre-autonomic” Basque government (of which EE was part), drafted a Statute of Autonomy (Irvin and Rae 2001, p.80), with consent from the Spanish parliament, that granted a Basque parliamentary assembly with extensive powers, as well as its own police force, and a special economic status (Basque Government 1979): it was approved by referendum by over 90% of voters. The first Basque elections in 1980 saw similar results to the 1979 elections: HB claimed 16.55% of votes (and 11 Basque assembly members), while EE obtained 9.82% (and 6 Basque assembly members) (Basque Government 2011). The PNV won the elections and was only short of a majority, but HB’s absence (El Pais 1981) allowed it to form the first Basque autonomous government.

The dates of the Spanish transition to democracy are not universally agreed upon. The shortest estimates date it from Franco’s death (1975) to the first elections (1977). However, the Basque Country was reacting to its own processes, and the beginning of Basque democratisation can be traced to 1974 (Soldevilla 2007, p.1), which is also the year of the the formation of ETA(pm). As for the end date, it is not 1980, the year of the first Basque autonomous elections, but 1982 that was more politically relevant. 1982 is a crucial date not only for Basques but for all Spaniards: the PSOE won a landslide in the 1982 elections, forming the first government formed fully of young politicians with no links to the Dictatorship. In the Basque Country, by 1982 Euskadiko Ezkerra had transformed itself from an electoral coalition set up by ETA(pm), to a fully-fledged political party representing democratic abertzale views (Basque Government 2011). Simultaneously, ETA(pm) dissolved itself and declared a unilateral ceasefire.

From 1982, ETA(m) was to be known simply as ETA, that which would haunt the established Spanish and Basque democracies until the present day. García de Cortázar makes the distinction between two ETAs; the one that struck the dictatorship’s apparatus and was felt with hope, and the one that fights democracy and is seen as a nightmare (2005, p. 120), which is consistent with Woodworth’s definition that declares the conditionality of democracy for the use of the term “terrorism”. If the cutting point between legitimate political violence and terrorism is blurry between 1974 and 1982, from then on ETA is unequivocally a terrorist organisation. So-called “peace processes” have been attempted since then (Irvin and Rae 2001, p.85) but none successful due to the ETA’s unwillingness to drop the guns and accept the democratic consensus.

Northern Irish Democratisation: 1973, 1998

In this section, this dissertation will analyse the two most important attempts at settlement and at ending the conflict, of which democratisation was an integral part: the initial, and unsuccessful, attempt at Sunningdale, and the ultimately successful agreement reached at Belfast.

If 1978-1980 are the ‘years of lead’ in the Basque Country, for Northern Ireland they are 1972-1976 (see Appendix I): over 250 deaths every year, and an average of 316 deaths per year, of which 60 per cent were civilians, and 44 per cent of all deaths deaths during the Troubles. The first of these “years of lead’, 1972, was the deadliest year of them all. 479 people lost their lives, over half of which were civilians (The Guardian 2010).

It all started on Bloody Sunday. The Northern Irish Civil Rights movement was in full swing, and the PIRA and its loyalist counterparts had begun their battle. But the shooting of unarmed civilians in a peaceful protest by British Army, who had previously been seen as peace-keepers by Nationalist communities (Darby 2001, p.17), shifted loyalties and triggered the bloodiest period in any recent European conflict. The beginning of the Troubles is usually traced to the creation of the PIRA in 1969, but as Appendix I shows, 1972 was the real catalyst. The Provisionals saw a massive increase in their recruitment, and began attacking both British Army, and Loyalist paramilitary targets, while the UDA and UVF responded with deadly attacks on Republican paramilitaries and Catholic civilians. The huge number of deaths prompted the British government to suspend the Unionist-controlled Stormont assembly, and establish Direct Rule (Darby 2001, p.18), which would last intermittently until 2007.

Earlier on, nationalists’ distrust of the political situation had resulted in the failure to establish a single powerful political party to promote their interests; the nationalist vote was fragmented. However, the birth of the Social Democratic Labour Party in 1970 as part of the Civil Rights movement succeeded in uniting moderate Nationalists, and the SDLP the main Nationalist force during the negotiations that followed (Coogan 1987, p.446). But the Brits needed a long-term solution to this deadly conflict, and soon after this explosion of violence they began negotiations with all parties, including the Irish government, in what became known as the Sunningdale Agreement.

Sunningdale

Sunningdale mainly proposed two things: the establishment of a power-sharing regional executive, and a Council of Ireland through which the Irish government would have a consultative role in some matters of Northern Irish governance; i.e. the Irish dimension (University of Ulster 2011, CAIN 4). The new Northern Irish Assembly would be composed of around 80 members (compared to the 52 under Stormont), but most importantly elected under proportional representation (as opposed to FPTP under Stormont). The larger number of assembly members, combined with the electoral system, ensured fair representation for the Catholic community who at the time composed around 35% of the population (UU 2011, CAIN 6). The first (and only) elections under Sunningdale demonstrated an improvement in representation for the Nationalist communities, as the newly-formed SDLP became the second largest party with 19 (out of 78) seats, and formed the new power-sharing Executive alongside with the Ulster Unionist Party (UU 2011, CAIN 7). Now, the government would be directly accountable to both communities.

In keeping with old-school Republican tradition, Sinn Féin still refused to participate in the elections for the ‘partitionist assembly’. Nor it did please hardline Unionists, who opposed any power-sharing with Nationalists, or Irish involvement in Northern Irish affairs. After a Unionist general strike, Sunningdale collapsed and London reinstated Direct Rule (Coogan 1987, p.446). Sunningdale represented the first real attempt to solve the conflict, directly responding to the very high levels of violence. But unlike before the agreement that came a quarter of a century later, “war fatigue” (Darby and MacGinty 2000, p.63) had not yet fully kicked in and the radicals on either side were keen to continue fighting.

Sinn Féin and Gerry Adams

The Hunger Strikes of 1981 increased the Republican movement’s popularity, and forced Sinn Féin to develop and political and electoral strategy, initiating its transformation “from IRA support group to highly competitive electoral force” (Tonge 2009, p.165). The leadership of Gerry Adams from 1983 pushed it to start participating in elections; Sinn Féin won an (abstentionist) seat in the first Westminster elections it participated in (UU 2011, CAIN 7). By 1986, they dropped the traditional policy of abstentionism towards the Irish Dail in a controversial policy reversal (UU 2011, CAIN 1), leading a small hardline group to splinter off; the Continuity IRA/Republican Sinn Féin. Paradoxically, this was the same issue that led the Provisional camp to split off from the Officials less than twenty years earlier, but “the 1986 decision can be seen as the start of the political process which shaped the eventual peace process” (Tonge 2009, p. 169). Furthermore, the PIRA had by the 1980s adopted a Socialist ideology that resembled that of the original Officials: “our aim [is] to force a British withdrawal from Ireland and to establish a Democratic Socialist Republic” (RAND 2005, p.95)

Sinn Féin, moderated under Gerry Adams, had now evolved into “the solitary representative of republicanism, at the expense of that movement’s military tendencies” (Tonge 2009, p. 165). And it was Sinn Féin, not the Provisional IRA, that acknowledged the necessity of a political settlement and ultimately negotiated the historic compromise alongside the SDLP with the Unionists (Cronin 2009, p.44).

Belfast

After three decades of extreme political violence, a historical agreement was reached in 1998: Belfast. In its creation of a power-sharing assembly it was reminiscent of Sunningdale (UU 2011, CAIN 2), but was wider as it included a cross-community police force, devolution of justice powers, etc. Most importantly, it included the issue of decommissioning of paramilitaries’ weapons. Around the time of Sunningdale, the paramilitaries and violent forces were running the game; but Belfast demonstrates a shift towards political supremacy, which the paramilitary groupings could only accept. Furthermore, Belfast succeeded where Sunningdale failed, in including all political forces; according to a senior Irish official, “we really don’t see that you can have a stable settlement unless Sinn Féin and the Loyalists are present” (Darby and Macginty 2000, p.63) The Provisional IRA, as well as loyalist groups, recognised the necessity of the political settlement and stopped all armed activity for the sake of the population of Northern Ireland; “when the course of human history seems to be changing, removing a sense of timelines from a cause and entering a period of economic, political, and ideological transition […], there are tangible effects on [..] terrorist movements” (Cronin 2009, p.48). “Belfast” succeeded in bridging the gap between the two communities through institutions that they would both recognise: the Unionists were pleased at the continuation of the Union, while “Sinn Féin argued that its constitutional agenda was being advanced” (Cronin 2009, p.48). The agreement was respected by most paramilitary groupings, causing a dramatic de-escalation in violence. Since the 1998 Omagh bombing by republican disidents, 81 people have lost their lives (see Appendix I). While not insignificant, this number demonstrates a massive de-escalation that can be directly attributed to the agreement. In fact, less people have died in the thirteen years since ‘Belfast’ than in a single year of an “acceptable level of violence” (around 100 deaths) in the 1980s (Cronin 2009, p.44). The first elections for the new Stormont took place in 1998, but the power-sharing assembly did not become fully implemented and autonomous until the 2007 St Andrews Agreement (UU 2011, CAIN 8). Sinn Féin and the DUP became the two largest parties, overtaking the historical UU and SDLP, and led the new Northern Ireland Executive (UU 2011, CAIN 7).

Northern Ireland is now arguably fully pacified. The massive deescalation of political violence can be directly attributed to the peace agreement reached at Belfast, of which democratisation was a key component, but not the only one. The difference between the unsuccessful agreement (Sunningdale) and the ultimately successful one (Belfast) is the latter inclusion of paramilitaries within the democratic settlement, through decommissioning and the ceasefire. But perhaps more significantly, war exhaustion from so many years of violence and death was was allowed the success of the final agreement.

Political parallels and differences

Sinn Féin, PIRA and ETA(pm); dissident Republicans and ETA(m)

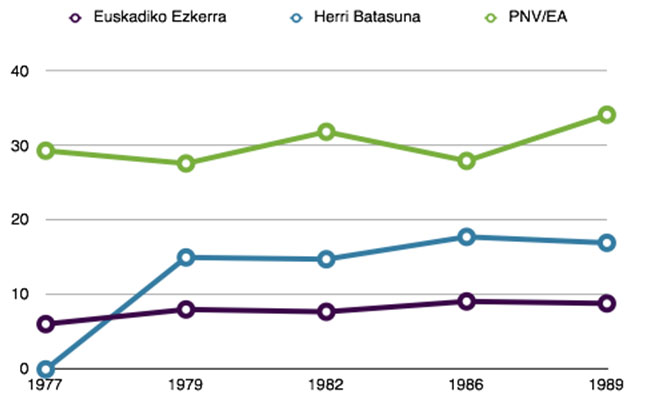

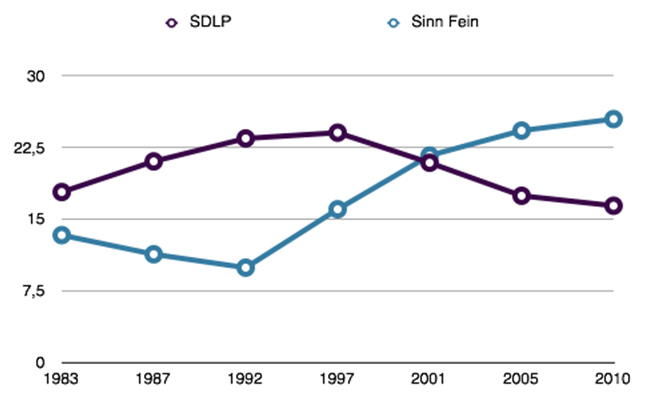

As has been argued throughout this dissertation, it is impossible to detach the final deescalation of violence from the internal transformations that occurred within the abertzale and the Republican movements. Interestingly, there are parellels to be seen between the Republican transformation of the 1980s, and ETA(pm)’s political history. The political development of Euskadiko Ezkerra and its detachment from military organisations mirrors Sinn Féin’s trajectory. On the other hand, the so-called “dissident republicans” (CIRA, PIRA, etc.) rejected their political process (Darby and MacGinty 2000, p.87) just as Herri Batasuna and ETA(m). However, while the so-called “political Republicans” ultimately prevailed over the “dissident Republicans” in Ireland, who only represent around 7 per cent of all nationalists (Tonge 2009, p. 176), the opposite is the case in Euskadi. The “political abertzales”, originally represented by Euskadiko Ezkerra, unfortunately claimed less support than the “military abertzales” of Herri Batasuna, as demonstrated by electoral results (see Appendix III). However, three decades of ETA’s illegitimate terror campaign against established democratic institutions have created a repulsion towards the organisation, which has led to its weakening and impending downfall. Only 3 per cent of Basques claim to even “critically justify” ETA, while 11 per cent agree with its goals but not its means, and 16 per cent claim to previously have supported ETA (Universidad del Pais Vasco 2010, p. 66). As graphically shown by Appendix III, the Good Friday agreement and the end of the PIRA campaign validated Sinn Féin’s political credentials, as it overtook the SDLP as the main Nationalist political party. But the same did not necessary occur with Euskadiko Ezkerra, whose performance remained relatively stable even after the dissolution of ETA(pm) and the finalisation of the democratic transition.

Social aspects

Despite similarities in political development, Northern Irish and Basque society differ greatly. Northern Ireland is a society entrenched by sectarian divisions (Keating 2001, p.184), of which the mutually exclusive British and Irish identities are a key issue. In 1968, only 15 per cent of Catholics labelled themselves as British, while only 4 per cent were a result of mixed marriages (Keating 2001, p.185). While there exists a variety of political options, the vast majority belong to one of two camps (2001, p.188). Democratisation in Northern Ireland, in the form of the various attempts and ultimately successful Good Friday Agreement, was seen as necessary to bridge the gap between the two communities with a power-sharing assembly, pacify the region and end political violence, and ensure equality and socio-economic rights. The democratic process was specific to Northern Ireland and responded to a local issue, was not part of a United Kingdom-wide transformation. Furthermore, democratisation was only a component of the wider “peace process”. On the other hand, in the Basque Country the division is one of political opinion, where identity is only a minor factor: 87% of those living in the region think of themselves as Basques, but 64% also think of themselves as Spanish (UPV 2010), demonstrating an overlap between the two identities. Obviously, ‘Spanish-ness’ is more common within the Spain-wide parties, and ‘Basque-ness’ within the Nationalist parties, but the distinctions is blurry when half of PNV-voters, the major representative of Basque nationalist opinion, see themselves as ‘equally Basque an Spanish’ (UPV 2010). Democratisation in the Basque Country was interlinked with the much wider process of Spanish political Transition. The Basque Country achieved further devolution, like Catalonia, but this was not as a result of ETA’s violence but of non-violent Basque desires for autonomy, a consensus accepted and encouraged by the Spain-wide parties as well. ETA rejected this consensus, and showed it by with an increase in its violence after 1980. The progressive reduction in the number of ETA victims (Appendix I) is a result of ETA’s weakening as an organisation, due to social rejection and “moral outrage” (USIP 1999, p.3) at the attacks and continued violence which has deprived it from societal legitimacy from which strength is ultimately derived; “public opinion is important because it strongly affects the amount of financial and operational support the terrorists enjoy” (USIP 1999, p.4).

Conclusion

This dissertations has answered the question through a close analysis of the political movements that created ETA and the Provisional IRA, tracing their internal development and ideological transformation, while rejecting the thesis that they can be analysed within some sort of worldwide pattern of terrorism, and argued that their existence (and demise), however influenced by foreign ideology, is a result of purely domestic processes as “terrorism is inseparable from its historical, political, and societal context” (Cronin 2009, p.199). Using a definition appropriate to the processes analysed here, this analysis has also determined that at their emergence these two organisations can not so easily be called “terrorist” because they responded to a situation where democracy was not in place. But ultimately, once democracy is achieved terrorism loses support progressively which illegitimises the group and creates its downfall: “marginalisation form their constituency is the death-knell for modern groups” (Cronin 2009 p.203).

ETA was born as a Basque nationalist organisation that sought to fight the Franco regime, but throughout the political process, more moderate factions split off, leaving an organisation of radicals only committed to the use of military action. But democratisation did not end ETA, because ETA rejected democratisation. Instead, the already-marginalised and radicalised ETA continued to strike against the newborn democracy. Its members represent a very small minority of Basques, but a determined one. While democratisation has not ended political violence in the Basque Country, it has delegitimised ETA, which due to societal pressure and rejection has become an extremely weak organisation, and whose future prospects are grim.

The Provisional IRA emerged as part of a wider movement to fight Unionist hegemony, through an Irish Republican ideology while advocating a United Ireland. However, similarly to ETA(pm), one can point out a political transformation within the Republican movement, and more significantly Gerry Adams’s Sinn Féin, that demonstrates its acceptance of political processes in motion and a reversal of some past policies. Unlike ETA, the PIRA accepted and recognised the necessity of the peace process, of which democratisation was a key component of. By Woodworth’s definition it is difficult to class the Provisional IRA at its emergence as a terrorist organisation because democracy was not necessarily in place, but once an agreement was reached which ensured a democratic compromise, the Provisionals stood down. The splinter factions which rejected ‘Belfast’, such the Continuity IRA and the Real IRA, can be compared to the post-1982 ETA, not only for their rejection of the democratic process, but for their current extremely marginal social support. They continue to exist and to strike, but this militant Irish republicanism “lacks a mandate” (Patterson 2011) and societal legitimacy for the simple reason that legitimate democratic institutions are now in place, which allow the people of Northern Ireland to determine their future.

As concluded by the United States Institute of Peace, “political violence by itself can rarely achieve its aims, but it can sometimes do so in conjunction with less violent political action” (1999, p.1). Inversely, democratisation on its own does not bring down political violence. But it ultimately achieves something that anti-terrorist policing cannot, by rotundly removing any claim of legitimacy that these groups may have had. Democracy legitimates the institutions through popular suffrage, while it rejects groups that attempt to bypass those democratic processes through the use of violent action that does not require being voted for.

Bibliography:

ABC (2010) Especial ETA. Available from: http://www.abc.es/especiales/eta/historia/index.asp [accessed 18 may 2011].

Apter, D.E. (1997) ‘Political Violence in Analytical Perspective’, in D.E. Apter. (ed.) The Legitimisation of Violence. London: Macmillan, pp.1-27.

Bloomfield, D. (1997) Peacemaking Strategies in Northern Ireland: Building Complementarity in Conflict Management Theory. London: Macmillan.

Coogan, T. P. (1987). The IRA. 3rd ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

COVITE (2010) Víctimas Mortales del Terrorismo. Available from: http://www.covite.org/covite_balancedolor.php [accessed 2 may 2011].

Cronin, A.K. (2009) How Terrorism Ends: Understanding the Decline and Demise of Terrorist Campaigns. Princeton UP.

Darby, J. and MacGinty, R. (2000) ‘Northern Ireland: Long, Cold Peace’, in J.Darby and R.MacGinty (ed) The Management of Peace Processes. London: Macmillan.

Darby, J. (2001) ‘Contemporary Peace Processes. Profile: Northern Ireland’, in J. Darby (ed) Effects of Violence on Peace Processes. Washington DC.: US Institute of Peace, pp.15-25.

El Pais (1981). El Rey defiende en Guernica la democracia y las instituciones vascas. Available from: http://www.elpais.com/articulo/espana/JUAN_CARLOS_I/_REY/PAIS_VASCO/ESPANA/PAIS_VASCO/HERRI_BATASUNA_/HB/PAIS_VASCO/PARLAMENTO_HASTA_2001/Rey/defiende/Guernica/democracia/instituciones/tradicionales/vascas/elpepiesp/19810205elpepinac_2/Tes [accessed 19 may 2011].

García de Cortázar, F. (2005). El Nacionalismo Vasco. (s.l): Biblioteca Historia 16.

The Guardian (2010) Deaths in the Northern Ireland Conflict since 1969. Available from: http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/datablog/2010/jun/10/deaths-in-northern-ireland-conflict-data [accessed 20 april 2011].

Fernández Soldevilla, G. (2007) ‘El nacionalismo vasco radical ante la transición española’, Historia contemporánea, 35, pp. 817-844. Available from: http://www.paralalibertad.org/descargas/Nacmo_radical_Transicion.doc [accessed 20 april 2011].

Hanley, B. and Millar, S. (2010) ‘The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Worker’s Party’, Irish Political Studies, 25(3), pp.457-471.

Irvin, C. and Rae, J. (2001) ‘Violence and Its Implications. Profile: Spain and the Basque Country’, in J. Darby (ed) Effects of Violence on Peace Processes. Washington D.C: US Institute of Peace, pp.77-85.

Keating, M. (2001), ‘Case Study: Northern Ireland and the Basque Country’, in J. McGarry (ed), Northern Ireland and the Divided World: Post-Agreement Northern Ireland in Comparative Perspective. Oxford UP, pp.181-206.

Loughlin, J. (2003) ‘New Contexts for Political Solutions: Redefining Minority Nationalisms in Northern Ireland, the Basque Country and Corsica’, in J.Darby and R.MacGinty (ed) Contemporary Peacemaking: Conflict, Violence, and Peace Processes. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.38-48.

Mees, L. (2003). Nationalism, Violence, and Democracy: The Basque Clash of Identities. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Partido Nacionalista Vasco (1995). Ponencia Politica: Asamblea General 1995. Available from: http://www.eaj-pnv.eu/documentos/documentos/751.pdf [accessed 20 april 2011].

Patterson, G. (2011). The IRA is a tradition, not an army. It hasn’t gone away. The Guardian (online) 26 April. Available at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/apr/26/ira-tradition-army-martin-mcguinness [accessed 30 April 2011].

RAND (2005). Aptitude for Destruction Volume 2: Case Studies of Organizational Leanings in Five Terrorist Groups, pp.93-138. Available from: http://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/2005/RAND_MG332.pdf [accessed 20 april 2011].

Rapoport, D.C. (2004). ‘The Four Waves of Modern Terrorism’, in Cronin, A.K. (ed) Attacking Terrorism: elements of a grand strategy. Georgetown UP.

Spain, Basque Government (1979) Estatuto de Autonomía para el País Vasco. Available from: http://www.euskadi.net/r33-2288/es/contenidos/informacion/estatuto_guernica/es_455/adjuntos/estatuto_ley.pdf [accessed 10 may 2011].

Spain, Basque Government (2011) Resultados electorales en Euskadi. Available from: http://www.euskadi.net/emaitzak/indice_c.htm [accessed 12 may 2011].

Spain, Ministry of Interior (2011). Victimas de ETA. Available from: http://www.mir.es/DGRIS/Terrorismo_de_ETA/ultimas_victimas/p12b-esp.htm [accessed 12 may 2011].

Tonge, J. (2009). ‘Republican Paramilitaries and the Peace Process’, in Barton, B. and Roche, P.J. (ed.) The Northern Ireland Question: the Peace Process and the Belfast Agreement. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Turk, A.T. (2004) ‘Sociology of Terrorism’, Annual Review of Terrorism, 30(2004), pp.217-286.

United States Institute of Peace (1999), How Terrorism Ends: Special Report. Available from: http://www.usip.org/publications/how-terrorism-ends [accessed 12 may 2011].

Universidad del Pais Vasco (2010). Euskobarómetro: Noviembre 2010. Available from: http://alweb.ehu.es/euskobarometro/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=98&Itemid=118 [accessed 18 may 2011].

University of Ulster. Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN). Available from: http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/ [accessed 15 april 2011].

1. Abstentionism – http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/abstentionism/chron.htm

2. Belfast Agreement – http://www.cain.ulst.ac.uk/events/peace/docs/agreement.htm

3. Bloody Sunday – http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/events/bsunday/sum.htm

4. Constitutional Proposals – http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/cmd5259.htm

5. Decommissioning – http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/events/peace/decommission.htm

6. Population and vital statistics – http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/ni/popul.htm

7. Results of Elections – http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/politics/election/elect.htm

8. St Andrews Agreement Timeline – http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/nistandrewsact221106.pdf

9. The Sunningdale Agreement – http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/events/sunningdale/chron.htm

Woodworth, P. (2001). Dirty War, Clean Hands: ETA, the GAL and Spanish Democracy. Cork UP.

Appendix I: Deaths in the Conflicts

Appendix II: Splits within the Republican and abertzale movements

ETA: Source: (García de Cortazar 2005, ch. 7 Fernandez Soldevilla 2007)

V Assembly: 1967

VI Assembly: 1970

2nd VI Assembly: 1974

IRA: Source:(Coogan, T.P. 1987, University of Ulster, CAIN)

colour coding represents the equivalent military/political wings

Provisional split: 1969

INLA split: 1974

Continuity split: 1986

“Real” split: 1997

(‘Good Friday Agreement’: PIRA and INLA ceasefire): 1998

Appendix III: Electoral performance of Basque and Irish Nationalist parties

Basque Country: Source: Basque Government 2011.

Performance of Nationalist parties in Spanish general elections, as percentage of Basque vote

Northern Ireland: Source: University of Ulster, CAIN 7.

Performance of Nationalist parties in UK general elections, as percentage of Northern Irish vote

—

Written by: Roberto Robles Fumarola

Written at: University of Sussex

Written for: Dr. Shane Brighton

Date written: May 2011

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Political Violence and Terrorism in Cyberspace

- Violence and Political Order: Galtung, Arendt and Anderson on the Nation-State

- Taiwan’s Democratisation and China’s Quest for Cross-Strait Reunification

- How Effective is Terrorism in Exerting Political Influence: The Case of Hamas?

- “The Women in White” – Protesting for a Peaceful Political Emancipation in Belarus

- Havoc to Hope: Electoral Violence in the Kenya 2022 General Election