As a consequence of overhauling its fundamental ideological structure, the demise of the Soviet Union can be described in its crudest terms as “a case of the therapy killing the patient (Crow, 1995, p48)”. On December 8 1991, the leaders of the Russian Federation, Belarus and Ukraine (the founding members of the USSR) convened secretly at the Belovezhsky Nature Reserve outside Minsk to sign the ‘Belovezhsky Treaty’, burying the former Soviet Union once and for all (Coleman, 1996, p353). As Boris Yeltsin exclaimed soon after, “the USSR, as a subject of international law and geopolitical reality, ceases to exist (Crawshaw, 1992, p223)”.

As co-signatories of the ‘Treaty on the Creation of the USSR’, its dissolution raised questions about the future directions of Ukraine and Belarus. One such question was centred on the abolition of the Soviet national identity and the requirements for a new doctrine of national identification that would unite the newly independent states. As founding members of the USSR and the subsequent Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the processes of reaffirming identity in the post-Soviet era in Belarus and Ukraine have taken their own unique pathways. Unlike a number of other former Soviet republics, neither Ukraine nor Belarus have successfully cemented themselves within the Western or Russian geopolitical code and both straddle the divide of civilizations between Western Europe and Orthodoxy (Allison et al, 2005, p487-88). Huntington’s ‘Clash of Civilizations’ thesis claims that deep divisions are “much more likely to emerge within a cleft country, where large groups belong to different civilizations (1996, p137)”. Ukraine is a state torn “between the Uniate nationalist Ukrainian-speaking west and the Orthodox Russian-speaking east (1996, p138)”. In contrast, geographical positioning has impacted minimally on Belarus, as the encompassing Russian sphere of influence has made it “in effect, part of Russia in all but name (1996, p164)”.

Therefore, as both share similar Soviet histories and now find themselves adapting to post-Soviet autonomy, the subtle differences of identity reaffirmation that exist between Belarus and the Ukraine make the two states compatible for a comparative study. This essay endeavours to examine European and Soviet identities within Belarus and Ukraine whilst geographically locating conflicting identities and acknowledging the reasons for these differences.

Nationalism represents a collective identity, but one that maintains the capability to change under certain conditions. The constructivist Alexander Wendt claims that “identities and interests are constituted by collective meanings that are always in process (1992, p397)”. Alternatively, nationalism is conveyed as an imagined concept by Benedict Anderson who argues that “the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion (1983, p6)”. Belarus has never been able to sustain these required pre-conditions of national consciousness to support the construction of nationalistic ideas or a collective imagined community (Titarenko, 2007, p79). As a common ethno-cultural identity has failed to successfully unite the Belarusian population at any point in history (Kuzio, 2002, no page), discussions on Belarus within this essay are less about identity reaffirmation and more about identity affirmation. Pre-Soviet nationalism in Ukraine was largely confined to the Western regions, where national consciousness developed in the 19th century following conflict in the East Galicia region between ethnic Ukrainians and Poles (Subtelny, 2000, p2). However, for the majority of their history, Ukrainians have fallen under the rule of foreign leadership and “had little opportunity to develop a distinctive high culture, define their common interests, develop a sense of national identity or even delineate their borders (Subtelny, 2000, p2)”. Therefore, Belarus and Ukraine differ substantially from their neighbours in the outer Soviet empire as civil society and national identity have had to be reinvented rather than merely resurrected (Munck, 1994, p361).

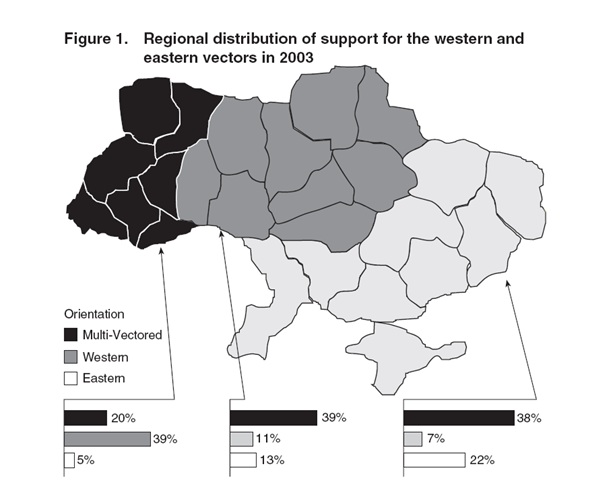

A key issue to address following independence was whether to turn to the West or turn back to the familiarities of the East. Initially it was believed that Belarus would orient itself towards the West as it surrendered its nuclear arsenal (Charnysh, 2008, p65) and initiated a partnership agreement with the European Union. However, following Stanislau Shushkevich’s defeat in 1994 to Alexander Lukashenka, Belarus adopted a Sovietophile ideology with a historiography heavily orientated towards a collective East Slavic identity and the additional presence of institutions representative of the Former Soviet Union (Kuzio, 2001, p170). Similar feelings of nostalgia exist within the Ukraine, but identities are heavily regionalised in comparison to Lukashenka’s authoritarian regime in Belarus. An 11 million strong Russian minority living in Eastern-Southern Ukraine have divided the population between Soviet and Ukrainian identities (figure 1), preventing the development of a cohesive national community. (Nemiria, 2000, p188). Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine has been maintaining a multi-vectored identity at the crossroads of East and West (White et al, 2010, p350).

Figure 1 – Map of Ukraine highlighting the political support for Eastern and Western vectors (Emerson, 2007, p215)

National identity remains weak in Belarus largely due to the continued popularity of Lukashenka and his authoritarian grip over the nation. Described by former US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice in 2005 as “the last remaining true dictatorship in the heart of Europe (CNN, no page)”, the Belarusian government have been “particularly skilful in mobilizing a certain brand of nationalism (Ioffe, 2007, p349)” by relaying contradictory messages to the general public. A strong ally to the Kremlin and extensively reliant on Russian trade, Belarusian national identity has been unable to separate itself from its Soviet past. Ukrainian identity on the other hand has developed sufficiently enough to prevent a return to the paternal Soviet ways, but not enough to mirror the “return-to-Europe” policies seen in the Baltic States. Therefore, whilst Belarusian identity is largely ambivalent and passive, the Ukrainian path to identity reaffirmation remains muddled somewhere between the Belarusian and Baltic policies (Kuzio, 2002, no page).

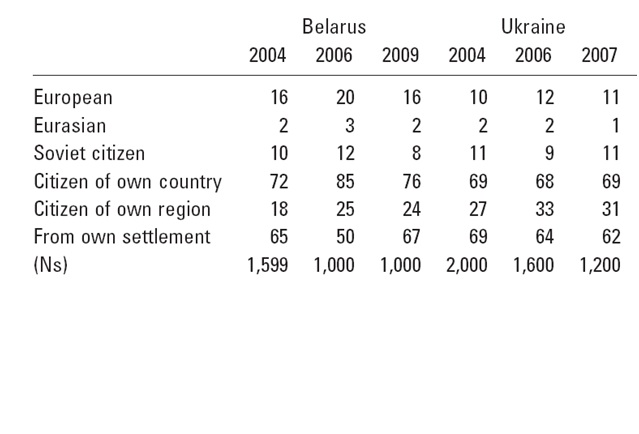

Whilst Belarus and Ukraine adopt unique geopolitical codes, contemporary public opinion towards both a European identity and a Soviet identity are heterogeneous features that highlight distinctions between the populations. Ukraine was the first of the post-Soviet states to declare its interest in joining the European Union in the late 1990s, yet support for accession has been declining over the last decade (Korosteleva and White, 2006, p194). Ukraine was overlooked during the EU expansions in 2004 and 2007 whilst Romania, a state viewed as similarly aligned with the Ukrainian transformation in the eyes of many Ukrainians was included (Wolczuk, 2004, p16). Perhaps surprisingly, there was a stronger sense of being European as a primary or secondary identity in Belarus than in Ukraine (figure 2), even though the frequency of this identity came a long way behind identification with Belarus (White et al, 2010, p352).

Figure 2 – Table highlighting self identification of Belarusians and Ukrainians. Question asked – “Which of the following do you think of yourself to be first of all? And secondly?” (White et al, 2010, p352).

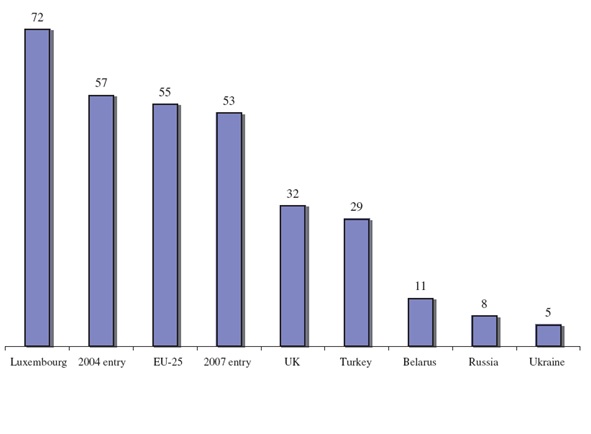

The languishing connection between Belarusians and Ukrainians to Europe is amplified in comparison to the same statistic for Turkey. As a predominantly Asian nation with a large European diaspora, nearly six times as many Turks identified themselves with Europe compared to Ukrainians (figure 3).

Figure 3 – Chart showing the variation across Europe of those declaring a primary or secondary European identity (White et al, 2010, p353).

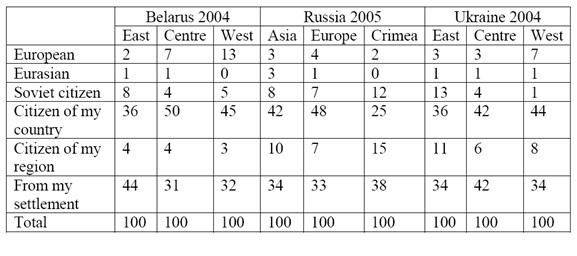

Deconstructing Europeanness in Belarus and Ukraine to the regional scale draws attention to the very pronounced geographical differences that exist. A higher number of people living in Western regions identify themselves with Europe and a larger number of the Eastern populations identify with the Former USSR (figure 4) (Korosteleva and White, 2006, p197).

Figure 4 – Table highlighting self identification by whether people live in the East, West or Centre. Question asked – “Which of the following do you think of yourself to be first of all?” Table also includes statistics for Russia (Korosteleva and White, 2006, p197).

These regional differences can be explained primarily through linguistic processes. As stated by Grigory Ioffe, “language may indeed be viewed as an important agent of nation building (2007, p371)”. The Belarusian language was gradually phased out during the process of Russification and this legacy has continued through discourses of prestige and higher education in association with the Russian language. In Ukraine however, there is a larger linguistic divide amongst the population. There is a large minority of 11 million ethnic Russians living in Ukraine who state Russian as their primary language (Bugajski, 2000, p165). Most of these Russian speakers occupy large parts of Eastern and Southern Ukraine and their presence has influenced the dynamics of Ukrainian-Russian relations (Barrington, 2002, p457). Historically, language has played an integral role in the construction of national identities (see Anderson 1983, Calhoun 1997) and as Duara notes, even when linguistic, religious or racial differences are present, nationalism is often considered to override these identities by way of a superior collective understanding (1996, p161). However, as nationalism has been historically weak in Ukraine, a cohesive identity has failed to unequivocally prevail over linguistic divisions. This was weakened further by the policies of former President Leonid Kuchma, who during his reign devolved greater power to individual regions. His liberal policies were aimed at consolidating a homogenous Ukrainian identity but instead produced contradictory results and led to further regional divisions (Kuzio, 2002, no page).

The Crimean region of Ukraine in particular contains a strong ethnic Russian community ideologically aligned to that of Belarus. National identity has been weak and unable to successfully re-affirm itself in Belarus and South-Eastern Ukraine due to a scarcity of structures capable of uniting the populations through popular mobilisation. Following the fall of the iron curtain, participation in civil society across all post-communist states has remained low (Howard, 2002, p161). Civil society is defined as “a form of societal self-organization which allows for co-operation with the state whilst enabling individualism (Hall, 1998, p32)”. Howard bases his explanation for low levels of participation upon three assumptions. Firstly, the USSR forcibly eradicated any independent group activities and instead constructed mandatory state controlled organizations. This in turn has produced a “deep, lasting, and negative effect of people’s mistrust of communist organizations and their membership today (2002, p162)”. Secondly, the private network of friends that developed under communism has remained intact and a mentality has emerged whereby people feel less comfortable expressing themselves freely with people outside of this closely knit network (2002, p162). Finally, Howard comments on how post-communist citizens have become disenchanted with the new political and economic systems initiated since independence. This despondency “has only increased the demobilization and withdrawal from public activities in the years since the collapse of communism (2002, p163)”.

In Belarus there has been little nationalist opposition to Lukashenka’s authoritarian regime since coming to power in 1994. The government has been thoroughly disciplined to prevent the development of civil society organizations (CSO’s), repressing the mechanisms that enable “pluralism of social opinion (Eke and Kuzio, 2000, p539)” to be conveyed to the internal structures of state power. Attempts were made from 1997 onwards to suppress the progressive role of NGOs in Belarus by imposing abnormally large fines for supposed financial irregularities. The consequence of CSO suppression has been the loss of one of the “institutional manifestations of the nation (Shils, 1995, p111)”, without which the functional processes of existing as a nation come into question. Combining this with the dominant Soviet-Belarusian identity, the extent to which Belarus can be defined as a modern nation is open to debate.

A further reflection of Belarusian identity can be found in the South-Eastern regions of Ukraine where civil society is also weak. On the whole, Ukrainian civil society is adequately developed (Kuts, 2001, p5), but the inability to collectively re-affirm national identity has caused an uneven distribution of CSOs. As Czarnota claims, “without state capacity and national integration, Ukraine is unlikely to be able to build a robust civil society (1997, p99)”. Without a strong civil society in place, mobilization for political change had remained modest until the Orange Revolution in 2004. However, as discussed in the following section, the passive features of the CSO deprived and industrial East have hindered Ukrainian national identity as it struggles internally between the forces of Western democratisation and Soviet authoritarianism.

Identifying the differences in 21st century ‘revolutionary’ events in both Ukraine and Belarus accentuate the contrasting progress of national identification reaffirmation in the post-Soviet era. The Orange Revolution in Ukraine in 2004 “came as a result of interaction between various factors, the most important being the role of civil society, national identity, the nature of political institutions and the modes of external pressure (Nemyria, 2005, p53)”. Following allegations of electoral fraud and corruption, Ukraine finally saw the rise of a powerful civic movement that marked a turning point in post-Soviet Eastern Europe, provoking a “seismic shift Westwards in the geopolitics of the region (Karatnycky, 2005, p35)”. Support for the Orange movement was primarily located in the same Western-Central regions that had called for democratization during the latter stages of Soviet rule. Arel (2005) identifies the distinct national identity found in the Western and Central regions as well as the ambiguities and low mobilisation found in the East (p6). The strength of identity particularly in the Galicia region underpinned the revolutionary process (p5). Furthermore, the role of Kyiv in the revolutionary movement is not to be underestimated as it provided “logistics, finances, local political support and tolerance on the part of its inhabitants whose city centre was blocked for 17 days (Kuzio, 2010, p292)”. The pro-Western Orange Revolution in 2004 exposed the developing maturity of national identity in Ukraine, but also highlighted the divide that persists between East and West.

The Orange Revolution laid the foundations for the failed attempt of Belarusian dissidents to stage their own colour revolution in 2006. This movement, dubbed the ‘Jeans Revolution’, amplified the continued vacancy of a strong collective national identity. Whilst support was initially large, it quickly faded and Lukashenka was able to restore order. As outlined by Markus (2010), there was little chance of any success from the outset due to the unfavourable pre-revolutionary conditions (p118). High levels of political repression against civil societies and protesters were combined with state media obstruction, lack of cohesion, limited material support and large swathes of support for Lukashenka (p118). This significantly contrasted the pre-conditions of the Orange Revolution whereby a sense of national identity had for some time been gaining momentum in the Western and Central regions of Ukraine.

Independence from the Soviet Union has led to both similarities and differences in the reinvention of national identities in Belarus and Ukraine. Identity in the Ukraine has been sharply polarised whereby more people identify themselves as either ‘strongly east’ or ‘strongly west’ (White et al, 2010, P361). National consciousness in Belarus has remained weak due to the strong affiliation with Russia and the role of the Lukashenka administration in suffocating any alternative movements. Whilst similar weaknesses are present in Eastern-Southern Ukraine, a well developed national identity in other regions has blocked the potential rise of a Belarusian style authoritarian government. The establishment of a strong civil society in its eastern and central regions has been one of the successes of an independent Ukraine, a success that is starkly contrasted in Belarus. However, the 2006 demonstrations have given hope that a national identity is quietly under construction in Belarus (Titarenko, 2007, p89) and that the ‘culture wars’ will intensify when Lukashenka’s government is replaced (Ioffe, 2007, p368). Belarusian identity is still within its infancy due to the strong Russian influences and the active role of the Belarusian government to prevent the rise of civil society organizations. In contrast, Ukrainian identity has developed sufficiently enough to separate itself from Russian influences. However, a new Western orientated identity in Ukraine is not a foregone conclusion as the Russian dominated east continues to obstruct the potential for a collective identity.

References

Allison, R. et al (2005) ‘Belarus between East and West’. Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics. 21(4):487-511.

Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined communities: reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London: Verso.

Arel, D. (2005) ‘The “Orange Revolution”: Analysis and Implications of the 2004 Presidential Election in Ukraine’. Third Annual Stasiuk-Cambridge Lecture on Contemporary Ukraine. http://www.ukrainianstudies.uottawa.ca/pdf/Arel_Cambridge.pdf (Last accessed 2/11/2010)

Barrington, L. (2002) ‘Examining rival theories of demographic influences on political support: The power of regional, ethnic, and linguistic divisions in Ukraine’. European Journal of Political Research. 41:455-491.

Bugajski, J. (2000) ‘Ethnic Relations and Regional Problems in Independent Ukraine’ . In Wolchik, S. and Zviglyanich, V. Ukraine, The search for a national identity. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

Calhoun, C. (1997) Nationalism. Buckinghamshire: Open University Press.

Charnysh, V (2008) Russia and Ukrainian denuclearisation: Foreign policy under Boris Yeltsin. http://charnysh.net/Documents/Charnysh_Volha_HonorsProject.pdf (Last accessed 2/11/2010).

CNN (2005) Rice: Belarus is dictatorship. http://edition.cnn.com/2005/WORLD/europe/04/20/rice.belarus/ (Last accessed 2/11/2010).

Coleman, F. (1996) The decline and fall of the Soviet empire: Forty years that shook the world, from Stalin to Yeltsin. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Crawshaw, S. (1992) Goodbye to the USSR: The collapse of Soviet Power. London: Bloomsbury.

Crow, S. (1995) ‘“New thinking” and the collapse of the Soviet bloc’. In Tolz, V. and Elliot, I. The demise of the USSR. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Czarnota, A. (1997) ‘Constitutional Nationalism, Citizenship and Hope for Civil Society in Eastern Europe’. In Pavkovic, A., Kosharsky, H. and Czarnota, A. Nationalism and Postcommunism. A collection of Essays. Aldershot: Dartmouth.

Duara, P. (1996) ‘Historicizing National Identity, or Who Imagines What and When’. In Eley, G. and Suny, R. Becoming National. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Eke, S. and Kuzio,T. (2000) ‘Sultanism in Eastern Europe. The Socio-Political Roots of Authoritarian Populism in Belarus’. Europe-Asia Studies. 52(3):523-547.

Emerson, M. (2007) ‘Ukraine and the European Union’. In Hamilton D. and Mangott, G. The New Eastern Europe: Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova. Washington, DC: Center for Transatlantic Relations.

Hall, J. (1998) ‘The Nature of Civil Society’. Society. 35:32-41.

Howard, M. (2002) ‘The weakness of post communist civil society’. Journal of Democracy 13(1):157-169.

Huntington, S. (1996) The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Ioffe, G. (2007) ‘Culture Wars, Soul-Searching, and Belarusian Identity. East European Politics and Societies. 21(2):348-381.

Karatnycky, A. (2005) ‘Ukraine’s Orange Revolution’. Foreign Affairs. 84(2):35-52.

Korosteleva, J. and White, S. (2006) ‘‘Feeling European’: The view from Belarus, Russia and Ukraine’. Contemporary Politics. 12(2): 193-205.

Kuts, S (2001) ‘Deepening the Roots of Civil Society in Ukraine. Findings From an Innovative and Participatory Assessment Project on the Health of Ukrainian Civil Society’. CIVICUS Index on Civil Society Occasional Paper Series. 1(10):1-28.

Kuzio, T. (2001) ‘Transition in post-Communist states: Triple or quadruple?’ Politics. 21(3)168-177

Kuzio, T. (2002) ‘National identity and democratic transition in post-Soviet Ukraine and Belarus: A theoretical and comparative perspective (part 1)’. RFE/RL East European Perspectives. 4(15).

Kuzio, T. (2002) ‘National identity and democratic transition in post-Soviet Ukraine and Belarus: A theoretical and comparative perspective (part 2)’. RFE/RL East European Perspectives. 4(16).

Kuzio, T. (2010) ‘Nationalism, identity and civil society in Ukraine: Understanding the Orange Revolution’. Communist and Post-Communist Studies. 43(3):285-296.

Markus, U. (2010) ‘Belarus’. In O’Beachain, D. and Polese, A. The Colour Revolutions in the Former Soviet Republic: Successes and Failures. Abingdon: Routledge.

Munck, G. (1994) ‘Democratic transitions in comparative perspective’. Comparative Politics. 26(3):355-375.

Nemiria, G (2000) ‘Regionalism: An underestimated Dimension of State-building’. In Wolchik, S. and Zviglyanich, V. Ukraine, The search for a national identity. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

Nemyria, H. (2005) ‘The Orange Revolution: explaining the unexpected’. In Emerson, M. Democratisation in the European Neighbourhood. Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies.

Shils, E. (1995) ‘Nation, Nationality, Nationalism and Civil Society’. Nations and Nationalism. 1(1):93-118

Subtelny, O. (2000) ‘Introduction: The Ambiguities of National Identity: The Case of Ukraine’. In Wolchik, S. and Zviglyanich, V. Ukraine, The search for a national identity. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

Titarenko, L. (2007) ‘Post-Soviet national identity: Belarusian approaches and paradoxes’. Filosofija Sociologija. 18(4):79-90.

Wendt, A. (1992) ‘Anarchy is what states make of it: The social construction of power politics’. International Organization. 46(2):391-425.

White, S. et al (2010) ‘Belarus, Ukraine and Russia: East or West?’ The British Journal of Politics and International relations. 12(344-367).

Wolczuk, K. (2004) ‘Integration without Europeanisation: Ukraine and its Policy towards the European Union’. EU Working Papers. RSCAS No. 2004/15

—

Written by: Lewis Green

Written at: University of Sheffield

Written for: Professor Paul White

Date written: October 2010

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Political Use of Soviet Nostalgia to Develop a Russian National Identity

- “The Women in White” – Protesting for a Peaceful Political Emancipation in Belarus

- Understanding Power in Counterinsurgency: A Case Study of the Soviet-Afghanistan War

- Identity in International Conflicts: A Case Study of the Cuban Missile Crisis

- Recreating a Nation’s Identity Through Symbolism: A Chinese Case Study

- Was There a Soviet-led Menace to Global Stability and Freedom in the Late 1940s?