The demobilisation of combatants during or after conflict is a crucial step towards achieving sustainable peace. Demobilisation is defined as ‘the formal disbanding of military formations and, at the individual level, as the process of releasing combatants from a mobilised state’.[1] When executed, it is part of a sequence of programmes labelled Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR). The former refers to the turn-in of weapons, the latter to the re-absorption of ex-combatants into civilian society. DDR has been an integral part of peace processes around the globe since 1989, when it was first implemented by the United Nations Mission in Central America (ONUKA).

In policy, programming and academic circles, the reintegration stage of DDR generally attracts most attention. It is assumed that reintegration is the most difficult phase and that demobilisation is a relatively unproblematic issue, conceived as a ‘technical exercise of reallocating personnel’.[2] This failure to acknowledge the difficulties and challenges in the demobilisation phase may jeopardise the DDR process and cause a post-conflict rise in crime levels, as ex-combatants turn to illegal activities.[3]

In the past decades, Colombians have become known as ‘serial demobilizers [sic]’[4]. This makes it an appropriate case in point to analyse the difficulties of demobilising combatants. The first section of this essay will briefly discuss the history of demobilisation in the Andean nation. Considering that each group has specific demobilisation challenges, depending on its nature, size and agreements with the government, this essay will then turn to one particularly problematic group in Colombia’s recent demobilisation history: the right-wing paramilitary organisation Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC). The circumstances under which the AUC demobilisation took place will be discussed, followed by an analysis of the three main difficulties: the ongoing conflict, the incoherence of the AUC organisation and the AUC’s connections to criminal organisations. Failure to tackle these issues in the demobilisation process, it will be argued, laid the foundations for the emergence of new criminal groups, Bandas Criminales Emergentes, commonly referred to as BACRIM. The demobilisation of the paramilitaries in Colombia did thus not represent a step forward towards peace, but a side-step towards a new phase in its civil war.

I. History of demobilisation in Colombia

The roots of the Colombian armed conflict lie in La Violencia (1948-53), a period of irregular violent confrontations in small towns and rural areas between supporters of the Liberal and Conservative parties. From this period sprang seven left-wing guerrilla groups, who based their struggle on grievances about inequalities, social marginalisation and the elitist control of political power. Their ultimate goal was the establishment of a socialist state.

The Marxist guerrillas were countered by local right-wing self-defence groups, as the government did not have enough power, resources and legitimacy to control its remote territories. In 1997, these paramilitary groups organised themselves in the AUC.

Five out of seven guerrilla organisations demobilised under peace negotiations between 1989 and 1994.[5] Two groups still continue their armed struggle today: the Fuerzas Armadas Revoluncionarias de Colombia-Ejército del Pueblo (FARC-EP, founded in 1964) and the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN, founded in 1962). Attempts at negotiations for their demobilisation have gone as far as creating a zona de despeje for the FARC-EP in 1998, yet have so far been unsuccessful.

Drug cultivation in Colombia has grown in line with the escalation of the conflict.[6] Particularly after the successful anti-narcotics campaigns of the Bolivian and Peruvian government in the mid 1990s, coca leaf cultivation and cocaine production moved to Colombian soil.[7] 90% of street cocaine in the United States is now Colombian-grown.[8] After the collapse of the drug cartels in the late 1990s, the insurgent groups took control of much of the narcotics industry.[9] The FARC-EP now relies on gramaje, a production tax on drug trafficking and production, for around 60% of its income.[10] The paramilitaries also thrive on revenues from drug production. AUC leader Carlos Castaño in 2000 admitted 70% of AUC income came from drugs.[11]

II. AUC demobilisation

In 2002, the AUC entered exploratory talks about demobilisation with the Colombian government under Alvaro Uribe. By then, it consisted of some 10,000-15,000 combatants.[12]

The incentives for AUC to enter the peace process were five-fold.[13] First of all, tensions within the leadership and competition between different paramilitary blocs undermined the viability of a national paramilitary organisation. Secondly, the public opinion towards the paramilitaries was changing, as their atrocities against civilians became more widely known. Additionally, some paramilitary leaders used the peace process as a way to prevent extradition to the United States on drug trafficking charges. Yet others wanted to gain more political and social influence and, finally, many low-ranking combatants hoped to return to their families.

In July 2003, the Santa Fe de Ralito agreement was signed, committing the AUC to demobilise entirely by December 2005. Under a second accord in May 2004, it was established that paramilitary leaders would assemble in a designated area while their crimes were investigated. A major bottleneck in the negotiations was the justice provision of the agreement: the paramilitaries wanted to avoid long prison sentences, even for grave human rights abuses. The Ley de Justicia y Paz eventually passed Congress in 2005, setting the maximum penalty for ex-paramilitaries to eight years imprisonment.

The demobilisation programme of the Office of the High Commissioner of Peace consisted of several phases: sensitisation, preparation, concentration, demobilisation, verification and reinsertion.[14] In a period of 15-30 days, combatants were given accommodation, nutrition and medical assistance while their identity cards from the Comité Operativo para la Dejación de Armas (CODA) were issued. When it was verified they were not wanted for crimes, they entered an 18-month reintegration programme, which included training or education and a monthly stipend of US$155.[15] The process received minimal external funding, as it was heavily criticised for a lack of regulation.[16]

When the demobilisation was officially concluded in August 2006, a total of 31,671 paramilitaries had been formally demobilised.[17] There is a large discrepancy between this number and the estimated number of AUC-members before the demobilisation process (10,000-15,000). If the statistics were accurate, it would either mean that every AUC member had demobilised twice, or that non-AUC members were entering the demobilisation process.[18] Poor civilians might have passed themselves off as combatants to benefit from the stipend, as might drug dealers attempting to launder their crimes.[19] Moreover, both the AUC leadership and the Colombian government may have had an interest in advertising inflated numbers: the former for a stronger negotiation position, the latter to showcase successful demobilisation.[20]

The AUC demobilisation has had positive impacts, most notably the improvement of human security in Colombia.[21] Moreover, about 50% of the counter-insurgency operations of the Colombian military are now based on intelligence supplied by demobilised combatants.[22] Notwithstanding these successes, Rozema points out that despite their demobilisation, ‘the militias did not really understand the meaning of peace. They did not receive retraining to enable them to abandon their militarised views of society.’[23] The unaddressed difficulties of the AUC demobilisation and their consequences will now be discussed in further detail.

III. Difficulties of AUC demobilisation

The AUC demobilisation was complicated by the presence of three factors: the ongoing conflict, the incoherence of the AUC group and the relationships between the AUC and criminal organisations, particularly narco-trafficking networks. These three factors, which will be discussed in turn, have not been accounted for in the design of the demobilisation programme. This facilitated the rise of the new criminal groups, BACRIM.

IV.I Ongoing conflict – Security and Longevity

The fact that the AUC demobilisation took place amidst an ongoing conflict presents different types of problems. Fusato identifies ‘security’ and the ‘inclusion of all warring parties’ as two out of five preconditions for successful DDR.[24] Neither of these can be present in an ongoing conflict.

The ‘security vacuum’ that was created with the AUC demobilisation had to be filled by the Colombian state.[25] However, a lack of state legitimacy and resources caused failure to achieve this in remote areas, such as Catatumbo on the Venezuelan border.[26] This is reflected in the increasing demand for private security in Catatumbo.[27] Because the FARC-EP and ELN did not demobilise, there was a fear that the changing power balance would be abused by these guerrillas to reinforce their control over territory.[28]

In addition, the security of ex-AUC members remains problematic. There have been reports of assassinations of demobilised AUC-combatants by the FARC-EP.[29] These issues can only be resolved when all parties to the conflict demobilise at the same time.

Another aspect of the ongoing conflict, which is brought to the fore by Mats Berdal, is the impact of the longevity of conflict on the success of demobilisation.[30] The logistical and technical challenges of demobilisation are complicated by long-lasting conflict, through destroyed infrastructure, displaced populations and the weakening of public institutions. Additionally, combatants may have spent their entire adult life fighting, making the social army networks the only ones they are familiar with.[31] Indeed, Salvatore Mancuso, an ex-paramilitary leader, claims that many demobilised AUC-members ‘return to – or indeed never left – the only life they know.’[32]

IV.II Incoherence of AUC

Another major difficulty in the demobilisation of the AUC was its incoherence as a group. Rather than a conventional insurgency group with a relatively centralised command structure, the AUC was a loose coalition of groups that cooperated or opposed one another according to their needs.[33]

AUC members included three social groups: old security services of the collapsed drug cartels, regional land-owners and small- and medium-sized drug lords.[34] The latter often “bought” themselves into the AUC organisation by putting down millions of dollars for control of an AUC bloc.[35] These blocs were hence subject to different leaders with different motives, who may or may not benefit from demobilisation.

Various authors have emphasised the importance of sound data about the organisation to be demobilised, to plan programmes according to the specifics of the group.[36] The AUC was perhaps too diverse to design a comprehensive programme that would accommodate the needs of all blocs.

IV.III Criminal ties unaddressed

The risk that demobilised soldiers could threaten the peace process by turning to criminal activities when their expectations of DDR are not met, is widely recognised.[37] What is generally ignored, however, is the impact of pre-existing networks of insurgents and criminal groups on DDR. In the case of the AUC, with their extensive criminal involvement, the aforementioned risk is even more pronounced. In fact, some authors have argued that the AUC was closer to a criminal organisation than an insurgency group.[38]

Rather than just cooperating with criminal organisations, the AUC developed “in-house” criminal abilities to operate in narco-production and trafficking.[39] This transition of the AUC from a guerrilla-fighting organisation to a Mafia-like criminal group could be considered a motive for their demobilisation: the groups could become more flexible and efficient by shedding excess combatants through demobilisation.[40]

The AUC connections to criminal organisations remained unaddressed in the demobilisation. To achieve sustainable peace, however, the complete dismantlement of the networks of insurgents and criminal groups is crucial, alongside measures to prevent their replication or reconstruction.[41]

IV. Emergence of BACRIM – neoparamilitares?

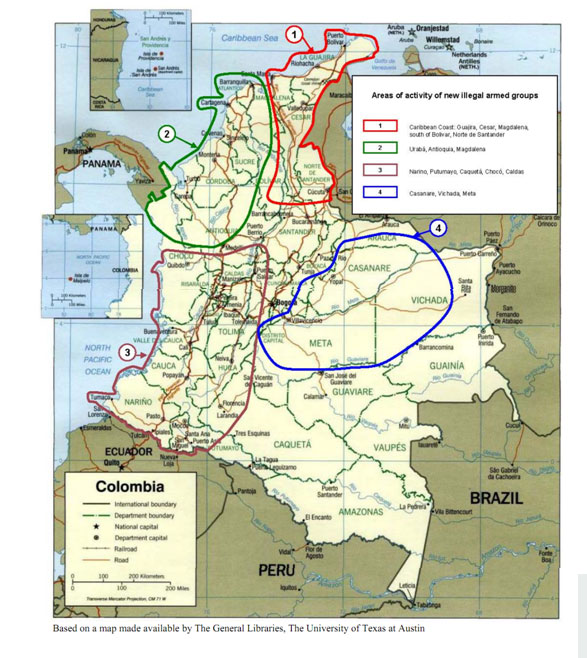

After the AUC demobilisation, reports about the emergence of new criminal groups around Colombia began to surface.[42] The Fundación Ideas para la Paz was one of the first organizations to warn about the rise of what they dubbed a “third generation of paramilitaries.”[43] The overarching desire of these groups, called BACRIM, is to control Colombia’s cocaine production and trade by seeking grip of seaports and border crossings. In February this year, the government under Juan Manuel Santos called the BACRIM ‘the new enemy’ in the civil war.[44]

Little data are available about the BACRIM. The Colombian government has identified 22 new armed groups, whose influence is manifested in four regions.[45] The police have estimated their size at about 7,000 members.[46] Some independent studies, however, have put the numbers as high as 84 groups with 9,078 members.[47] Some of these new groups, like Las Águilas Negras, openly affirm their ties to the AUC and are affiliated with the paramilitary political agenda and military tactics.[48] Others have a purely criminal orientation, and are even believed to cooperate with the FARC-EP and ELN for drug trafficking deals.[49] How many members of the BACRIM are ex-paramilitaries is unclear, although some estimate 17 percent.[50]

There are diverging analyses of the nature and origin of the BACRIM. These different analyses coincide with the three aforementioned problems of the AUC demobilization. Some believe that the security vacuum left behind by the demobilisation of the paramilitaries has been filled by the new armed groups. The weak state does not have the wherewithal to enforce the demobilisation agreement and as a result ‘enough bad actors remain to carry the violence forward.’[51]

Others stress that the incoherence of the AUC has caused some groups not to enter the demobilisation process, leading to smaller splinter movements.[52] Additionally, mid-level commanders have taken the opportunity to gain power they did not have under the AUC umbrella.[53] Berdal indeed emphasises that senior officers are a particularly sensitive group to demobilise, for their organisational power, management expertise, wealth and higher expectations.[54]

Yet others argue that the failure of the demobilisation process to remove the ties of ex-combatants to criminal networks, facilitated the rise of the BACRIM.[55] Indeed, both press and officials treat the BACRIM as paramilitaries in a new guise, using terms like ‘las herederas de los paramilitares’[56], ‘neoparamilitarismo’[57], and ‘reparamilitarisation’[58].

At the moment, the BACRIM do not yet hold the same amount of influence as the paramilitaries did. They are smaller, their control less evident and they fight among each other over strategic territories.[59] Yet they are also flexible and dynamic. The main concern of the Santos government is the possibility that the BACRIM will form a new federation that could become a new major belligerent in the Colombian conflict.[60]

V. Conclusion

In 2003, the World Bank warned that a structured DDR process is crucial to decrease the risk of ex-combatants resorting to illegal activities or rejoining insurgent groups to survive.[61] The demobilisation of the paramilitaries in Colombia has proved the veracity of this claim. This essay has demonstrated how the AUC demobilisation was complicated by three factors. The ongoing conflict caused security concerns, as well as problems associated with the effect of long-term fighting on combatants. Incoherence of the paramilitary group impeded the development of a comprehensive program that accommodated the needs of all combatants. Meanwhile, the criminal involvement of the AUC caused a web of social and economic ties that proved hard to unravel. An insufficient awareness of these difficulties in DDR programming, fostered the emergence of the BACRIM, which now pose a new threat to the country’s fragile security situation. The gravity of this threat is yet to be established.

It was beyond the scope of this essay to discuss the “individual” demobilisation that occurred alongside the “collective” demobilisation of the AUC. This work has also omitted the 2006 “parapolitics scandal”, in which multiple members of Congress have been indicted for cooperation with the AUC. Rather, it has tried to show, within the limited space, that from the seeds of AUC demobilisation has not grown peace, but a new type of armed actor in the forest of the Colombian conflict.

Bibliography

Abbott, Edith (1927), ‘The Civil War and the Crime Wave of 1865-70’, Social Service Review, Vol. 1, No. 4,

Alden, Chris (2003) ‘Making Old Soldiers Fade Away: Lessons from the Reintegration of Demobilised Soldiers in Mozambique’, The Journal of Humanitarian Assistance. Available: http://jha.ac/articles/a112.htm [Accessed 15-03-2011].

Álvarez, Pedro Trujillo (2010), Impacto de la percepción y de la realidad de la violencia. Estudio de un caso: Guatemala. Centro de Estudios Hemisféricos de Defensa.

BBC News (17 February 2011a) ‘Profiles: Colombia’s armed groups’. Available: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-11400950 [Accessed 14-03-2011].

BBC News (17 February 2011b) ‘Q&A: Colombia’s civil conflict’. Available: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-12447532 [Accessed 14-03-2011].

Berdal, Mats (1996), ‘Disarmament and Demobilisation after Civil Wars’, Adelphi Papers, Vol. 303, No.

Caramés, Albert, Fisas, Vicenç & Luz, Daniel (2006), ‘Analysis of Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR) programmes existing in the World during 2005’, Escola de Cultura de Pau, Vol., No.

Castells, Manuel (18 September 2001) ‘La guerra red’, El Pais. Available: http://www.elpais.com/articulo/opinion/guerra/red/elpepiopi/20010918elpepiopi_8/Tes [Accessed 17-03-2011].

Collier, Paul (1994), ‘Demobilization and Insecurity: A Study in the Economics of the Transition from War to Peace’, Journal of International Development, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 343-351

Comisión Colombiana de Juristas (2008) ‘Neoparamilitarismo y nuevas masacres’, Boletín No 29. Available: http://www.coljuristas.org/Portals/0/Bolet%C3%ADn%20No%2029%20sept%202008.pdf [Accessed 19-03-2011].

Forero, Juan (5 September 2007) ‘New Chapter in Drug Trade. In Wake of Colombia’s U.S.-Backed Disarmament Process, Ex-Paramilitary Fighters Regroup Into Criminal Gangs’, The Washington Post. Available: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/09/04/AR2007090402018.html [Accessed 10-03-2011].

Fundación Ideas para la Paz (12 August 2005) ‘La tercera generación’, Siguiendo el conflicto: hechos y análisis de la semana, Número 25. Available: http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:http://www.ideaspaz.org/publicaciones/download/boletin_conflicto25.pdf [Accessed 170-03-2011].

Fundación Seguridad & Democracia (2004), La Desmovilización del Bloque Bananero de las AUC.

Fusato, Massimo (2003) ‘Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration of Ex-Combatants’. Available: www.beyondintractability.org [Accessed 10-03-2011].

Guáqueta, Alexandra (2003), ‘The Colombian Conflict: Political and Economic Dimensions’, in Ballentine, Karen and Sherman, Jake ed., The Political Economy of Armed Conflict. Beyond Greed & Grievance, (London: Lynne Rienner Publishers), pp. 73-106

Guáqueta, Alexandra (2007), ‘The way back in: Reintegrating illegal armed groups in Colombia then and now’, Conflict, Security & Development, Vol. 7, No. 3, pp. 417-456

Guáqueta, Alexandra & Arias, Gerson (2009), Impactos de los programas de desmovilización y reinserción sobre la sostenibilidad de la paz: el caso de Colombia.

Guha-Sapir, D. & Panhuis, W. van (2002), Mortality Risks in Recent Civil Conflicts: A Comparative Analysis (Brussels: CRED)

Hansen, Art & Tavares, David (1999), ‘Why Angolan Soldiers Worry about Demobilisation and Reintegration’, in Black, Richard and Koser, Khalid ed., The End of the Refugee Cycle? Refugee Repatriation and Reconstruction, (New York: Berghahn Books), pp.

Harris, Caleb (12 March 2007) ‘Paramilitaries reemerge in pockets of Colombia’, The Christian Science Monitor. Available: http://www.csmonitor.com/2007/0312/p04s01-woam.html [Accessed 10-03-2011].

Hitchcock, Nicky (2004), ‘Disarmament, demobilisation & reintegration: The case of Angola’, Peacekeeping, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 36-40

Human Rights Watch (3 February 2010) ‘Paramilitaries’ Heirs’. Available: http://www.hrw.org/en/node/88058/section/9 [Accessed 20-03-2011].

International Crisis Group (10 May 2007), Colombia’s New Armed Groups. Latin America Report No. 20.

Koth, Markus (2005), ‘To End a War: Demobilization and Reintegration of Paramilitaries in Colombia’, Bonn International Center for Conversion, Vol., No.

Marriage, Zoë (2007), ‘Flip-flop rebel, dollar soldier: demobilisation in the Democratic Republic of Congo’, Conflict, Security & Development, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 281-309

Muggah, Robert (2005), ‘No Magic Bullet: A Critical Perspective on Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) and Weapons Reduction in Post-conflict Contexts’, The Round Table, Vol. 94, No. 379, pp. 239-252

Porch, Douglas & Rasmussen, María José (2008), ‘Demobilization of Paramilitaries in Colombia: Transformation or Transition?’, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, Vol. 31, No. pp. 520-540

Posada, Cristina Villegas de (2009), ‘Motives for the Enlistment and Demobilization of Illegal Armed Combatants in Colombia’, Peace and Conflict, Vol. 15, No. pp. 263-280

Reuters (27 August 2007) ‘Nine Colombians Killed in Suspected Rebel Massacre’. Available: http://www.reuters.com/article/2007/08/27/us-colombia-rebels-idUSN2740173220070827 [Accessed 19-03-2011].

Ronderos, Juan G. (2005), ‘The War on Drugs and the Military: the case of Colombia’, in Beare, Margaret E. ed., Critical Reflections on Transnational Organized Crime, Money Laundering, and Corruption, (Toronto: Toronto University Press), pp. 205-236

Rozema, Ralph (2008), ‘Urban DDR-processes: paramilitaries and criminal networks in Medellín, Colombia’, Journal of Latin American Studies, Vol. 40, No. pp. 423-452

Saab, Bilal Y. & Taylor, Alexandra W. (2009), ‘Criminality and Armed Groups: A Comparative Study of FARC and Paramilitary Groups in Colombia’, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, Vol. 32, No. 6, pp. 455-475

Salazar, Hernando (17 February 2011) ‘Las Bacrim asustan a Colombia’, BBC Mundo, . Available: http://www.bbc.co.uk/mundo/noticias/2011/02/110217_colombia_bacrim_ao.shtml [Accessed 14-03-2011].

Sanín, Francisco Gutiérrez (2008), ‘Telling the Difference: Guerrillas and Paramilitaries in the Colombian War’, Politics & Society, Vol. 36, No. 1, pp. 3-34

Serrano, Mónica & Toro, María Celia (2002), ‘From Drug Trafficking to Transnational Crime in Latin America’, in Berdal, Mats and Serrano, Mónica ed., Transnational Organized Crime & International Security), pp. 155-182

Sida (May 2008), Maras and Youth Gangs, Community and Police in Central America. Summary of a regional and multidisciplinary study.

Stankovic, Tatjana & Torjesen, Stina (2010), Fresh Insights on Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration: A Survey for Practicioners. NUPI.

The Economist (21 October 2004) ‘Colombia’s paramilitaries and drug lords: Lording it over Colombia’, The Economist. Available: http://www.economist.com/node/3317964 [Accessed 20-03-2011].

Theidon, Kimberly (2007), ‘Transitional subjects: the disarmament, demobilization and reintegration of former combatants in Colombia’, International Journal of Transitional Justice, Vol. 1, No. pp. 66-90

Tilly, Charles (1985), ‘War Making and State Making as Organized Crime’, in Evans, Peter, Rueschemeyer, Dietrich and Skocpol, Theda ed., Bringing the State Back In, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp.

Appendix I – Map of Colombia, areas of new armed group activity

Source: International Crisis Group, (10 May 2007), p. 29

[1] Berdal (1996), p. 39

[2] Marriage (2007), p. 292

[3] A so-called ‘crime wave’ after conflict has been recorded as early as the Napoleonic Wars (Abbott (1927)). Tilly (1985), p. 173, also describes how historically, ‘demobilized ships became pirate vessels,

demobilized troops bandits’. Guha-Sapir and Panhuis (2002) point out that after the peace processes in El Salvador and Guatemala, criminality and social violence rose above pre-war rates. Banditry also peaked after the civil wars in Liberia (Stankovic and Torjesen (2010)) and Mozambique (Alden (2003)). Collier (1994) found that demobilised Ugandan soldiers without access to land were 100 times more likely to commit a crime than the average Ugandan citizen.

[4] Porch and Rasmussen (2008), p. 521

[5] Although none have survived as a political party today, Guáqueta (2007) has argued they underwent a relatively successful political integration.

[6] Guáqueta (2003), p. 79

[7] Serrano and Toro (2002), p. 163-4

[8] BBC News (17 February 2011b)

[9] Ronderos (2005), p. 220

[10] Saab and Taylor (2009), p. 463-465.

[11] International Crisis Group (10 May 2007), p. 4

[12] Posada (2009), p. 265

[13] Rozema (2008), pp. 429-430

[14] Koth (2005), p. 26

[15] Caramés, Fisas and Luz (2006), p. 23

[16] Koth (2005), p. 27. The law meant to regulate the DDR process passed two years after demobilisation began.

[17] Porch and Rasmussen (2008), p. 528

[18] Ibid., p. 528

[19] In 2003, the High Commissioner for Peace said that only 30% of the 855 people demobilised as combatants of the Bloque Cacique Nutibara were actually paramilitaries. The majority belonged gangs and criminal bands. Ibid., p. 528

[20] Saab and Taylor (2009), p. 460

[21] Despite regional differences, the AUC demobilisation caused an average 16.04% homicide reduction, 12.39% theft reduction and 15.38% assault reduction (Porch and Rasmussen (2008), p. 530)

[22] Ibid., p. 530

[23] Rozema (2008), p. 434

[24] Fusato (2003). A political agreement, a comprehensive approach and sufficient funds are the three remaining preconditions.

[25] Koth (2005), p. 6

[26] The same is true for urban centres, that are often controlled by gangs or ´mafias´ (Theidon (2007))

[27] Fundación Seguridad & Democracia (2004), p. 4

[28] Koth (2005), p. 32

[29] Reuters (27 August 2007). Earlier demobilisations saw similar patterns. Out of 5,000 demobilised guerrillas between 1989 and 1994, 1,000 were assassinated (Guáqueta (2007), p. 418)

[30] Berdal (1996), p. 14

[31] Ibid., p. 17

[32] Quoted in Porch and Rasmussen (2008), p. 531

[33] Guáqueta and Arias (2009), p. 38

[34] Sanín (2008)

[35] The Economist (21 October 2004)

[36] Berdal (1996), p. 45; Hansen and Tavares (1999), p. 204; Collier (1994), p. 344

[37] Koth (2005), p. 38; Hansen and Tavares (1999), p. 207; Hitchcock (2004), p. 38

[38] Saab and Taylor (2009), p. 462. Whereas criminal groups are motivated by profit, insurgents pursue political goals. Evidence that the AUC had reduced political motives emerged in the demobilisation negotiations, when the AUC did not demand political reintegration but low sentencing for their crimes.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Koth (2005), p. 38

[41] Castells (18 September 2001)

[42] Similar patterns of increased criminal organisations can be observed after the peace processes in Central American countries such as El Salvador, Nicaragua and Guatemala. Álvarez (2010), Sida (May 2008)

[43] Fundación Ideas para la Paz (12 August 2005)

[44] Salazar (17 February 2011), BBC News (17 February 2011a)

[45] International Crisis Group (10 May 2007), p. 6; see Appendix I

[46] Salazar (17 February 2011)

[47] International Crisis Group (10 May 2007), p. 6

[48] Harris (12 March 2007)

[49] Salazar (17 February 2011)

[50] Porch and Rasmussen (2008), p. 463

[51] Ibid., p. 521

[52] Examples are blocs under “Martin Llanos” in Casanare and under “René” in Antioquia (International Crisis Group (10 May 2007), p. 5)

[53] Forero (5 September 2007)

[54] Berdal (1996), p. 48

[55] Koth (2005), p. 38; Rozema (2008), p. 444

[56] Human Rights Watch (3 February 2010)

[57] Comisión Colombiana de Juristas (2008)

[58] Porch and Rasmussen (2008), p. 530

[59] International Crisis Group (10 May 2007), p. 6

[60] Ibid., p. i

[61] World Bank report quoted in Muggah (2005)

—

Written by: Maite Vermeulen

Written at: King’s College London

Written for: Preeti Patel

Date written: March 2011

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Why Are Feminist Theorists in International Relations so Critical of UNSCR 1325?

- Has the US Learned from Its Experience in the Vietnam War?

- The Crime-Conflict Nexus: Connecting Cause and Effect

- Commemorating Srebrenica: The “Inadequate” Truth of the Female Victim Experience

- Double Agency? On the Role of LTTE and FARC Female Fighters in War and Peace

- To What Extent Can History Be Used to Predict the Future in Colombia?