Migration has become an eye-catching issue in the era of globalization. According to the World Migration Report 2010 (IOM, 2010), the scale of international replacement is astonishing. The number of international migrants, estimated to be 214 million in 2010, is at a record high; they account for 3.1 percent of the world’s population. The pace of the enlargement of migration has increased dramatically during the last few decades. It is reckoned that if the rate of migration continues at the same pace as during the last two decades, the total sum of international migrants will hit as many as 405 million by 2050. One key economic concern regarding international migration is the issue of remittances, to which particular attention should be paid. Remittances in 2009 were estimated to be around USD 414 billion, with developing countries receiving USD 316 billion. This number is the first recorded decline since 1985, due to the global economic crisis, but it remains above the levels prior to 2007 (ibid.).

There are some new trends and characteristics in recent international migration, the foremost of which is, of course, the unprecedented growth in both type and speed. There is a wider diversification in ethnic and cultural groups, while the numbers of female, youth and child, and illegal immigrants have grown; the circulation of temporary migration has also sped up (IOM, 2010). Specifically, the USA remains the number one destination for migrants. Compared to 43 percent in 1990, 57 percent of migrants lived in high-income countries in 2008, making up 10 percent of the total population of those countries. Most countries regard their level of immigration at present to be “satisfactory” (UN DESA, 2009).

Holding more than half of the world’s population, Asia is crucial in the discussion of global migration. In line with the development of global migration, Asia sees similar trends. One important evolution of Asian international migration is the diversification in type, among which overseas contract workers have become the biggest group (Hugo, 2004). The Philippines may be one of the countries most affected by global labour migration, with more than 1.4 million Filipinos hired abroad in 2009 alone (POEA, 2010a). The Filipino phenomenon can be attributed to strong policy support and government involvement. This essay will examine the case of the Philippines, addressing the government policy of exporting labour. In doing so, the focus is on legal mechanisms operating within officially recognized institutions.

The article is structured in the following way. At the outset, it is a compendium of migration in the Philippines, illustrating the situation at the present moment. Following that is a section that aims to explain the phenomenon of the upswing in migration, focusing on investigating the culture of migration in the Philippines. Third, labour export policy will be explored in search of underlying motivations for the government to embrace such a strategy. Finally, criticisms of the migration policy are reviewed, discussing merits as well as weaknesses, and the potential risks for implementing this approach.

Migration in the Philippines

As stated above, being one of the top 10 emigration countries in the world, the development of migration in the Philippines is associated with the larger picture of world trends. There are some similar features by and large; the dramatic explosion in scale, the diversification in destinations, increasing concerns regarding undocumented migration, the growing tide of female migrants, and so on. However, there are also some unique characteristics that are not shared by other major emigrant countries. The most distinctive feature is the proliferation of nonpermanent job-oriented migrants, or, in Hugo’s (2004) words, the “overseas contract workers.” Along with it, protection of the overseas workers raises great concerns. The economy in the Philippines depends heavily on remittances. The intensive involvement of government in emigration plays a crucial role. In other words, the Philippines has become an exporter, and its goods are its citizens.

These circumstances contribute to the current migration situation in the Philippines. CFO (2010) estimated that as of December 2009, there were around 8.6 million Filipinos working or residing outside the Philippines, or more than 10 percent of its population. Among them, roughly 4.1 million were permanent migrants, 3.8 million were temporary, and another 0.66 million were irregulars. They lived in 214 countries, with the US, Saudi Arabia, Canada, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Australia, Malaysia, Japan, the UK, Hong Kong, and Singapore listed as the top 10 destinations.

With specific regard to the exportation of labour, according to POEA (2010b), even during the difficult global recession, the Philippines still saw a successful year in 2009, demonstrating the country is a substantial provider to the world labour market. In this single year, which saw 15.1 percent year-on-year growth, there was an unprecedented 1.4 million overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) sent abroad. They arrived in more than 190 destinations. Notably, Filipino seafarers make up 23 percent of the world total.

In terms of remittances received from OFWs, the number amounted to a historical USD 17.3 billion, an unexpected 5.6 percent increase compared with 2008, and which accounted for 10.8 percent of the country’s GDP (ibid.). This proportion is impressively high compared with the 1.9 percent of GDP for all developing countries, and 5.4 percent of GDP for the group of low-income countries in 2009 (the World Bank, 2010).

Culture of Migration in the Philippines

From the statistics in the last section, it is obvious that migration has become a prevalent phenomenon in Filipinos’ lives. The Philippines can even be seen as having a culture of migration. In a survey from 2002, one in five adult respondents said they would like to migrate. The percentage increased in surveys carried out by Pulse Asia in 2005, which reported figures of 26 percent and 33 percent in July and October respectively. Interestingly, this is a common view, not only among adults, but also shared by children, as 47 percent of children aged 10 to 12 admitted their desire to work abroad in the future, in a nationwide survey carried out in 2003 (Asis, 2006).

The history of migration in the Philippines can be traced back centuries, with immigration and emigration within the region. Due to American control from 1898 until the mid 1900’s, “international migration” for Filipinos meant movement to the United States for much of the twentieth century. The first group of Filipino workers arrived in Hawaii in 1906, and more followed, expanding to California, Washington, Oregon, and Alaska. Most were single men. They took positions in agriculture, fisheries, and low-wage services such as restaurant and domestic work. It is reckoned that the total sum in the USA amounted to 150,000 between 1907 and 1930, most of whom were in Hawaii (Asis, 2006).

However, a “culture of migration” emerged only in the last 30 years, with the stimulus of the government encouraging people to work abroad. In 1934, the Tydings-Mcduffie Law (or the Philippines Independence Act) started to impose immigration quotas on Filipinos moving to the USA, which caused a dramatic decline in the number of migrants. The Second World War stalled migration to a greater extent. After the independence of the Philippines in July 1946, the situation recovered gradually.

The rapid upswing of migration started in the 1970s, which was pushed by high demand for labour in the oil-rich Gulf countries. Approved in 1974, the Labour Code of the Philippines established a governmental framework for overseas employment. Since then, international labour migration has become a long-lasting government policy. Facilitated by organized institutions and policies, the system of working abroad was ameliorated and became more convenient. Because of limited employment opportunities and significant differential wages, Filipinos strove to obtain a position in the world labour market despite high risks and uncertainties, as the national Economic Development Plan in 2001 stated that overseas employment is a “legitimate option for the country’s work force” (as cited in O’Neil, 2004).

Having personally benefited from the remittances sent by relatives or seeing the successful cases of others, working abroad has become an attractive option for most Filipinos. Although triggered by the government, the economic incentives later worked as a primary impetus for forming a migration culture.

Labour Export as a Government Strategy

This section will illustrate in the detail the government’s strategy of exporting labour, examining the supporting policies and institutions.

A Brief on the Labour Export Strategy

In the last three decades, labour export has been a way for the government to deal with high unemployment rates. Migrant workers are valued such that the “Baygong Bayani” (modern-day hero) is awarded to 20 outstanding Filipinos working abroad on Migrant Workers Day, the 7th of June every year. A sophisticated system has been developed to promote and regulate labour emigration.

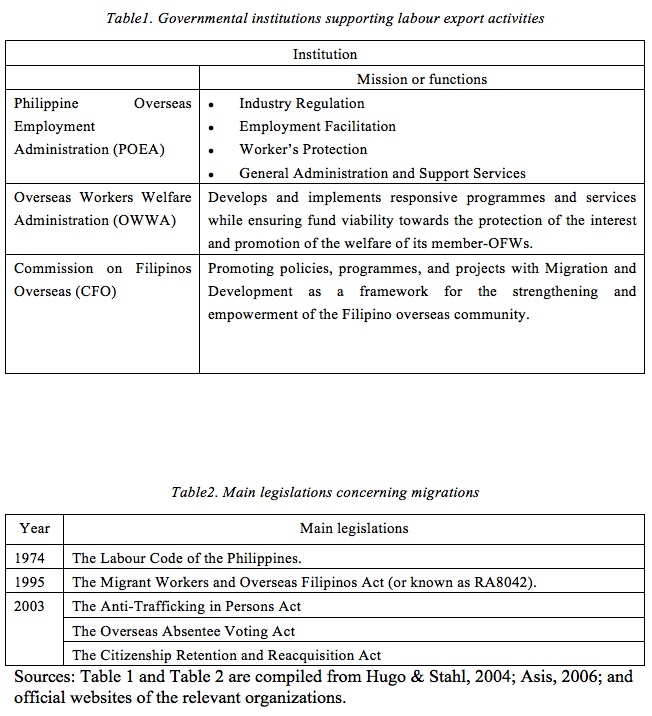

The Arab Oil Boycott in 1973 brought great benefits to the Gulf countries and sped up development in massive infrastructure. Therefore, a large labour force was needed to fulfill the construction boom. The Philippines, meanwhile, was in trouble with high unemployment, poor economic development, political instability, and low wages. Together, the factors of demand and supply urged the Filipino dictatorship to export workers. This was supposed to be a temporary solution, and once the country recovered, governmental intervention would be withdrawn (Asis, 2006). However, the continuing demand in the world labour market and stagnancy in domestic development turned the transition policy into a survival strategy. The establishment of democracy in 1986 did not change the economic situation or the outflow of migrant workers. Nonetheless, the government defined its goal clearly, stating that “Migration should be promoted, but only for temporary work via regulated channels” (O’Neil, 2004). Therefore, it is actually an employment-driven strategy. The specific governmental regimes involved in labour export are listed in Table 1 and Table 2.

How is Labour Exported?

The operation of exporting labour comprises both public and private sectors. Migrant workers can receive a set of comprehensive services throughout the stages of migration, from recruitment and pre-departure orientation, to return and remigration.

The national government has made efforts to promote the “Filipino workers” brand globally, and to protect workers’ rights. The POEA assumes responsibilities in managing and regulating processes, as well as providing services, before workers leave the country. It is also the main governmental agency involved in the recruiting process. However, migrant workers put through it only make up a very small proportion of the total. The OWWA is responsible for workers’ welfare while they are working abroad. The CFO specializes in covering permanent emigrants.

Private recruiters serving as middlemen, currently, have a much more fundamental role in Filipino labour exports. Since the government handed over the function of recruiting and matching workers to private recruiters in 1976, the recruiting industry has thrived, growing considerably from 44 agencies in 1974 to 3,168 agencies in 2007 (de los Reyes, n.d.). People looking for jobs abroad pay “placement fees” for the services of recruitment agencies. However, excessive fees are always charged, constituting one of the most common types of violations against migrant workers’ rights.

Both the public and the private components are required to work legally. Whether workers are recruited by the POEA or recruiting agencies, they are nonetheless under the authority of the Philippine government.

Rethinking the Labour Export Strategy: To Export or Not to Export?

This section will analyze the advantages and risks of the strategy and identify possible government responses to the issue.

Benefits of Exporting Labour

As mentioned before, the primary reason for the adoption of the labour export policy was to address a high unemployment rate. Therefore, the most straightforward benefit of the policy is providing an alternative to the domestic labour market. The rapidly growing population generates great pressure on the demand side, while the weak national economy could not offer sufficient job opportunities. Although initiated as a stop-gap solution, the outcomes were so positive that the policy continues today. This policy, thus, undoubtedly contributes substantially to the country’s stability.

At first, strengthening the country’s balance of payments was also a concern. As declared by then-dictator President Ferdinand Marcos, “if these problems are met or at least partially solved by contract migration, we [can] expect an increase in national savings and investment levels” (as cited in Oishi, 2005:63). Labour is not different from other exported goods, as they are all meant to garner foreign earnings.

Remittances are the second largest source of foreign funding, following foreign direct investment (Ratha, 2005: 20). As Hugo and Stahl (2004) conclude, remittances have fundamental significance with respect to the development of the economies of origin. Even though the majority of remittances flow to consumption, a great part remains invested directly in production. The multiplier effects also enlarge the impact of remittances consumed to promote development. At the micro level, remittances are the most important benefit individual families receive from the policy. The economic benefits help to improve the living standards of migrant workers’ relatives and eliminate poverty.

Unexpectedly, the policy also helps curb gender inequality in the Philippines. In the early days, men dominated the outflow of the labour force. However, more and more Filipinas have since joined the flow, and data shows that women have outnumbered men, as newly hired land-based workers through legal means since 1992 (Asis, 2006). The overturn can be attributed to the difficult domestic employment situation for females and the development of new demand in the global labour market. Employment situations for females are more difficult at home than for their male counterparts. At the same time, there is an increased demand for female workers and a decline for male workers (Semyonov & Gorodzeisky, 2005). Having achieved economic independence, Filipinas are more likely to make their voices heard.

There are other relatively tiny or controversial benefits of exporting labour; to provide training and skills for migrant workers that may prove useful after they return; to strengthen bilateral relations, which might in turn help with national development; and to alleviate disparate development in regions.

The Cost of Exporting Labour

There are, of course, numerous drawbacks to exporting labour. The foremost concern is the so-called “brain drain,” which refers to the loss of people with specific skills, high education, and training, who are needed for domestic development. For example, some argue that the Philippines lost a great number of the country’s best science graduates through emigration, and in 1992 alone, professional, managerial, technical, or administrative workers constituted 12 percent of all Filipino emigrants to the USA (Hugo, 2004). Then-Health Secretary Juan Flavier commented that the majority of medical graduates from the University of the Philippines in 1990 were in search of employment abroad, disregarding the lack of doctors in the country’s rural areas (as cited in Hugo, 2004:97). More ironically, because of the high demand for nurses in the global market, many Filipino doctors also switch to become nurses so as to have a better chance at employment (Asis, 2006).

Others are worried about the difficulties of protecting workers’ rights aboard. Migrants are in danger of rights encroachment. According to Asis (2006), “excessive placement fees, contract substitution, nonpayment or delayed wages, and difficult working and living conditions are common problems encountered by migrant workers, including legal ones.” The home country has no direct legitimacy in protecting workers, leaving them vulnerable. Despite some attempts to collaborate with destinations, the coverage is sporadic at best. Female workers working in “private” contexts like domestic service and entertainment are at particular risk.

Nonetheless, there is another crucial cost that might be easily ignored, the potential nonfeasance of government in development. In the case of the Philippines, the labour export policy only addresses the symptoms, but not the root causes. After years of implementing the policy, the factors shaping poor economic performance and the high unemployment rate have yet to be improved. Therefore the successes of the policy, extended the temporary policy and turned it into a survival strategy. Also, because of the global labour market, politicians do not have a sense of urgency in making progress.

Consequently, worries of national dependency are raised. The great reliance on the global market and remittances, or a lack of autonomous domestic economic strength, makes the Philippines vulnerable to external conditions that are out of its control. An evident example would be the Gulf War in 1990, which affected many sending countries, including the Philippines (Hugo & Stahl, 2004). Some Filipinos even regard this reliance as a source of “national shame” (ibid.).

In regard to remittances, there are also contentions. The perception that remittances reduce regional disparities assumes that they flow back home as a whole. As a matter of fact, the original disparities in poverty characterize chances of migration. As a result, a handful of districts usually benefit more from remittances than others. This may exacerbate inequalities among regions (Skeldon, 2008). Remittances usually flow directly to the micro-levels of families and individuals. In the Philippines, most of them are used to meet survival needs (food, better living standards), or reinvested into migration (education and training for better chances at working abroad). Placing remittances into investments is relatively limited. Skeldon (2008) points out that governmental interference to urge more usage of remittances for investment is likely to be counterproductive, and attempts at regulations or management of development-oriented usage fail to meet intended goals. Thus, the promotional effect of remittance on sustainable economic development is questionable.

To Export or Not to Export?

It is a dilemma that this strategy, with all its potential risks, has become a survival tactic that cannot substantially fuel the Philippine economy, but rather undermines or constrains substantial development to some extent. On the other hand, if the Philippines cannot improve its economic capacity, it cannot abandon the strategy. Despite the controversies, it is unlikely that there will be an end to the labour export strategy in the near future.

First of all, ordinary people do benefit from working overseas. It is undeniable that remittances alleviate poverty and increase well-being at a micro-level. For most individuals, the practical benefits they can acquire are much closer and more significant than larger national development or social improvement. Therefore, the strategy has strong support from citizens.

Second, the action of exporting labour is closely linked with the pace of globalization. The labour export strategy is only feasible in a globalizing context, with integration of world economies and markets. Generally speaking, globalization represents a growing integration of national economies, along with a diffusion of social, cultural, and political norms and practices all over the world. In the economic sphere, Emmerij indicates that “globalization is reflected in the increasing acceptance of free markets and private enterprise as the principal mechanisms for promoting economic activities” (1997:27). The overall process of globalization is a result of numerous factors, namely, expansion of capitalism and the rapid progress of technology. Globalization is a phenomenon driven mainly by the private sector (ibid.).

Although the government provides overarching guidance and legislation, the private labour export industry, comprising middlemen like recruiters, agencies, and lawyers, plays a crucial role in delivering and operating government policies. The industry not only profits from facilitating emigration, but also constitutes a vital component of the domestic labour market and absorbs a great deal of the labour force. Thus, the lobbying power of private industry should be taken into account when changing migration policies. In addition, the capacity to absorb the labour force and alleviate the domestic unemployment rate by industry itself, also requires policy-makers to be prudent in any consideration of policy changes.

Finally, the government itself is not willing to change. Besides the great economic costs, there are huge political costs to be considered as well. Exporting labour is a shortcut to addressing the unemployment problem, which is much easier to do than making substantial improvements to the economy. The short-sighted concern of pursuing re-election contributes to the prevention of radical changes being made to the strategy. Politicians would like to release the pressures of unemployment and maintain a stable society during their tenures.

Conclusion

Migration has recently become a hot topic in academia. However, much attention on governmental involvement in the migration process has concentrated on government attempts to control immigration, and less so on policies and programmes promoting emigration (Hugo & Stahl, 2004). The experiences of government efforts to shape population outflow in Asian countries demonstrate that state power is highly relevant in the scale and composition of emigration. Labour export policy has been adopted by many Southeast Asian countries, of which the Philippines is the most typical one.

The labour export strategy is stimulated by the process of globalization. The current tide of migration dates back to the 1970s, when demand for labour in the Gulf countries thrived. Being a leading emigration country, the variety and scale of Filipino migrants is impressive. The country relies highly on remittances received from migrant workers. The promotion of labour export contributes fundamentally to the generation of migration culture, which in turn motivates people to work abroad. Although initiated as a stop-gap policy, the labour export policy has turned out to be a survival strategy after years of development. The Philippine government has developed a set of sophisticated mechanisms to promote labour export, comprising public-private cooperation. Private recruiters are at the center of operating the emigration process.

There are benefits and risks regarding the strategy. It helps to solve the problem of high unemployment rates and enhances the national balance of payment. Remittances make up the second largest source of foreign funds in the Philippines. Gender equality is also promoted by labour export, because more Filipinas have become migrant workers. However, critics have pointed out the various costs of the strategy. The “brain drain” is still the foremost concern. Protection of migrant workers’ rights also draws great attention. The benefits may generate inertia and lead to potential nonfeasance of government, hindering the country from solving deeply rooted problems thoroughly and developing a substantial domestic economy. The great reliance on the global market makes the country vulnerable to external shocks. Remittances have not compensated for the social costs as people thought they might.

Despite these debates, however, the labour export strategy will be preserved and even enhanced in the foreseeable future. Opposition from ordinary citizens, related industry, and the government itself, combine to prevent radical policy changes on this issue.

References:

- Asis, M. (2006). The Philippines’ culture of migration. Migration Information Source. Migration Policy Institute. Available at http://www.migrationinformation.org/USFocus/display.cfm?ID=364 [accessed 17 February 2011].

- CFO (2010). Stock estimate of overseas Filipinos. Commission on Filipinos Overseas (CFO). Available at http://www.cfo.gov.ph/pdf/statistics/Stock%202009.pdf [accessed on 17 February 2011].

- de los Reyes, J. (n.d.). Are OFWs falling through the cracks?: Between unwieldy regulation and the middle men of migration. Focus on the Global South- Philippine Programme. Available at http://focusweb.org/philippines/content/view/224/52/ [accessed 17 February 2011].

- Emmerij, L. (1997). Development thinking and practice: introductory essay and policy conclusion. In Emmerij, L. (ed.) Economic and Social Development into the XXI Century. Washington: The Inter-American Bank, pp. 3-38.

- Hugo, G. (2004). International migration in the Asia-pacific region: emerging trends and issues. In Massey, D. and Taylor, J.E. (eds.). International Migration: Prospects and Policies in a Globalized context. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hugo, G. & Stahl, C. (2004). Labour export strategies in Asia. In Massey, D. and Taylor, J.E. (eds.). International Migration: Prospects and Policies in a Globalized context. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- IOM (2010). World migration report 2010: the future of migration: building capacities for change. International Organization for Migration (IOM). Available at http://publications.iom.int/bookstore/free/WMR_2010_ENGLISH.pdf [accessed 17 February 2011].

- Oishi, N. (2005).Women in motion: globalization, state policies, and labour migration in Asia. California: Stanford University Press.

- O’Neil, K. (2004). Labour export as government policy: the case of the Philippines. Migration Information Source. Migration Policy Institute. Available at http://www.migrationinformation.org/Feature/display.cfm?ID=191 [accessed 17 February 2011].

- POEA (2010a). Overseas employment statistics. Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA). http://www.poea.gov.ph/stats/2009_OFW%20Statistics.pdf [accessed 17 February 2011].

- POEA (2010b). POEA annual report 2009. Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA). Available at http://www.poea.gov.ph/ar/ar2009.pdf [accessed 17 February 2011].

- Ratha, D. (2005). Workers’ remittances: an important and stable source of external development finance. In Maimbo, S.M. and Ratha, D. (eds.). Remittances: Development Impact and Future Prospects. Washington, DC: World Bank, pp. 19-51.

- Skeldon, R. (2008). International migration as a tool in development policy: a passing phase? Population and Development Review, 34(1), pp. 1-18.

- Semyonov, M. & Gorodzeisky, A. (2005). Labour migration, remittances and household income: a comparison between Filipino and Filipina overseas workers. International Migration Review, 39(1), pp.45-68.

- The World Bank (2010). Issue brief: migration and remittances. Available at http://siteresources.worldbank.org/TOPICS/Resources/214970-1288877981391/Annual_Meetings_Report_DEC_IB_MigrationAndRemittances_Update24Sep10.pdf [accessed 17 February 2011].

- UN DESA. (2009). Trends in total migrant stock: the 2008 revision. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). Available at http://www.un.org/esa/population/migration/UN_MigStock_2008.pdf [accessed 17 February 2011].

—

Written by: Feina Cai

Written at: Institut Barcelona d’Estudis Internacionals (IBEI)

Written for: Professor Juan Diez Medrano

Date written: 02/2011

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Friend or Foe? Explaining the Philippines’ China Policy in the South China Sea

- Recreating a Nation’s Identity Through Symbolism: A Chinese Case Study

- The Race for the Arctic: A Neorealist Case Study of Russia and the United States

- Identity in International Conflicts: A Case Study of the Cuban Missile Crisis

- Water Crisis or What are Crises? A Case Study of India-Bangladesh Relations

- Understanding Power in Counterinsurgency: A Case Study of the Soviet-Afghanistan War