After recent public demonstrations for change in Libya, Muammar Gaddafi took retaliation: “Libya’s government has brought out its supporters to express their loyalty to try to stifle a planned ‘day of rage’” (Black, February, 2011). The need for international action became apparent after alleged aggression against rebels and civilians by the country’s regime. Henceforth, March 19th 2011 is a key date for the civilians of Libya, as it was marked by the United Nations (UN) resolution mandating a mission to enforce a ‘no-fly zone’, to be enforced by the French Air Force and the British Royal Air Force and associates of the international coalition (BBC News, March 19, 2011). Such action was widely welcomed by the rebel camp in Libya. Today, the coalition mission has been taken over by NATO, which has expanded the mission’s mandate. Although additional countries have joined the coalition, others such as Russia and President Dmitry Medvedev argued that such action was not authorized by the UN (The Sunday Times, April 17, 2011).

In the context of the Middle East uprisings of 2011, the Libyan unrest was the only one in which foreign intervention was deemed necessary because of the potential human cost (Bishara, 2011). This paper will attempt to rationalize the theoretical concept, or the reasoning, behind the humanitarian intervention which led France and the UK to enforce the ‘no-fly’ zone mandate. The methodology of this paper can be considered of liberal devise as Moravcsik (1997) discusses in his paper (p.545). Whilst the approach may seem unusual at first, Moravcsik (1997) develops in his article that such a proceeding bares value for the extension of theory; it is a proceeding that has its value for the extension of theories (p.547). By examining the coalition’s reasoning we will review key criteria. By doing so, the paper strives to assess the importance of the reasoning behind the intervention. In other words, this paper is not meant to defend or attack the reasons behind UK’s and France’s action. It is an opportunity to assess the story-line that took place and review it with a theoretical lens. The research question of this paper is therefore as follows:

The rational for enforcing the UNSC mandate 1970/73

As Wendt (1992) concludes in his article, all theories of international relations are based on social theories of the relationship between agency, process, and social structure. With this in mind, the choice of the theory does not matter as much as the study case that is chosen (p.422). Due to the large number of international relations, it seemed that in first instance, Neoliberalism, Neorealism and Normative Theory appeared to be the best suited to rationalize the intervention. The reason is that they are not only contemporary theories, but, each of them offers a rational which demonstrate the diverse conclusion that this case study could have i.e. use of military forces. Highlighting models in political science is a proceeding which scholars have done; quoting from Whang (2010) paper to name a few examples: Ordeshook and Palfrey 1988; Banks 1989; Lupia 1992; Lohmann 1993; Box-Steffensmeier, Arnold, and Zorn 1997; Diermeier and Feddersen 2000; Licaria and Meier 2000; Rogers 2001; Snyder and Ting 2002. This aims to demonstrate that the methodology of this paper is a proceeding which scholars have addressed previously. Whang stats in his paper that a vast number who are focusing on “international relations, implicitly or explicitly, rely on the idea of making it clear in explaining international politics (Schelling 1960; Martin 1993; Morrow 1994; Fearon 1994, 1997; Hall and Franzese 1998; Schultz 1999; Simmons 2000; Gartzke, Li, and Boehmer 2001; Guisinger and Smith 2002; Sartori 2002; Mansfield, Milner, and Rosendorff 2003; Leventoglu and Tarar 2008)” (p.381)[1]. Like Moravcsik (1997), this paper will attempt to address political science from a liberal international relation’s fundamental premise: “they specify the nature of societal actors, the state, and the international system” (Moravcsik, 1997, p.516).

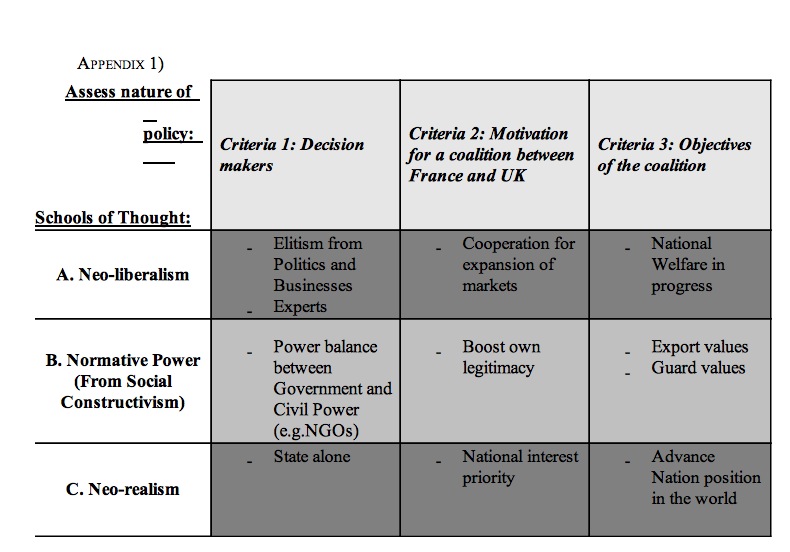

The paper is divided in two main chapters. The first chapter reviews the framework from a theoretical understanding. This chapter will define three different criteria, which will be used throughout the paper. These are ‘Decision makers’, ‘Motivation for a coalition between France and UK’ and ‘Objectives of the coalition’. The selection of these criteria is influenced by the three criteria that Moravcsik (1997) used in his own article. The main difference is that the premises of his criteria are depicted as assumptions, which are same as affirmations. This paper’s criteria are to be understood as tools in order to answer the research question, which translate the world seen through the theoretical lens in question. They will be demonstrated using the theory most suited seems for this study: Normative Power. The second chapter is divided into three sections. Each section focuses on one of the main criteria developed and their respective implication in real life action. Once the above criteria are addressed, the paper will answer the core research question in the conclusion.

The case study research was based on the following resources: relevant academic literature, media articles, and online information, e.g. Harvey (2006) and Manners (2002), or for the use of assessing the criteria in the second chapter, e.g. French Defence and National Security (2008) and Security Council (2011) which is the public transcript for the Mandate UNSC 1970/73 . In addition, I attempted to focus on the media from the Middle-East, e.g. Al Jazeera, instead of the usual Western sources. I believed that a media closest to the culture of the country in question would offer a different view than the ones that we are used to hearing. To counter balance potential subjectivity, the paper has also taken in account western media such as the BBC. My ‘European Studies’ allowed me to adopt a European academic perspective to the issue, analyzing it from a personal and broader standpoint. Naturally, different viewpoints are necessary. Therefore, the collection of various academic and scholarly viewpoints allowed for a more fundamental understanding of the theoretical framework. Their input was essential in order to remain as objective as possible. However, due to, at times, strong subjectivity in some texts, only the fundamental key facts were kept.

I. The theoretical framework

To conduct a successful analysis of the case study, three different theories will be examined. With the aim to demonstrate how these contribute to an understanding of the strategy of the UK and France in Libya. The theories in question are derived from two leading schools of thoughts and one concept; namely, ‘Neoliberalism’, ‘Neorealism’ and ‘Normative Power’ respectively. Since each of the mentioned theories would analyze any situation given from different perspectives, it was necessary identify three essential angles. These are ‘Decision makers’, ‘Motivation for international cooperation’ and ‘Objectives of the coalition’. The first one is an attempt to identify the decision makers and/or organizations that are responsible for the actions taken by the coalition. The second one is an attempt to look at the driving force which motivates France and the UK to work together. The third one is meant to understand the reasons and goals of the intervention. The results driven from these three angles will assess the impact of foreign relations of the coalition community “including the number and strength of the states in can ‘catch’ in its ‘net’ of consensual understanding” (Adler et al., 1992, p.389). Every theory (Baylis et al, 2011) offers a different perspective on those criteria, which is essential to help us understand motivation of the intervention.

This chapter relating to the theoretical framework is influenced by an analysis of the nature of relationships between the EU and China, which I was co-authored with various homologues in an unpublished paper for a University of Maastricht course ‘External Relations of the European Union’(Dorer et al., 2011). The subject matter discussed in the paper is deemed to be relevant as it also has as a goal to analyze the nature of the reasoning which motivated the EU to establish international relations with China. In this case, the focus is on the nature of reasoning of the UK and France towards Libya. The previous paper was an attempt to assess the nature of the relations the EU chose to pursue with China. This paper is attempting to look at the interaction between UK, France and Libya from an academic perspective. Hence, it is not an attempt to critic, but, to attempt to understand the overall motivation and reasoning of France and UK, with the UNSC.

The International Relations Theories

To assess the interpretation of the three criteria, it is helpful to explain and define the three theories. This sub-chapter is meant to highlight the specific understanding of the words ‘Neoliberalism’, ‘Neorealism’, ‘Normative Power’ and their synonyms.

The school of thought known as Neoliberalism is concerned with defending individuals and their rights over the government. The following phrase from Harvey (2007, p.64) summarizes the main aspects of Neoliberal theory and what it defends: “According to the theory, the neoliberal state should favour strong individual private property rights, the rule of law, and the institutions of freely functioning markets and free trade.”

However, the application and theoretical framework of Neoliberalism are not always coherent: “The practice of Neoliberalism has […] evolved in such a way as to depart significantly from the template that theory provides” (ibid.). This complexity arises when the theory is put into practical terms. In other words, it is primarily concerned with the instruments used to help market development. There are times when the government does not support democracy blindly, and situations where it is seen as an undesirable system and attacked: “Governance by majority rule is seen as a potential threat to individual rights and constitutional liberties” (ibid, p.66). In summary, direct democracy is not a perfect system with regard to market priorities. Moreover, sometimes reluctantly, Neoliberals may prefer indirect democracy with only a few actors in society such as experts and elitists holding decision-making power (a definition of this point will follow). Individuals are responsible for their welfare and actions, and a society which is governed by the majority will not function successfully as there is no feeling of unity, except unity in disarray.

Neoliberalism (Baylis et al, 2011, chapter 8) attempts to understand international cooperation, integration, the promotion of economic exchange and economic liberalization. This view point examines aspects of motivations used to analyze the actions of the coalition in Libya. Overall, the theory argues the need for an international supranational body to oversee the relations between governments.

The second theory discussed in this chapter is Neorealism. According to Stevenson (2007, p.52) “Human beings simply wish to protect and preserve their bodily integrity, and such integrity is threatened by the unpredictability of natural human interaction”. According to Neorealist theorists such as Stevenson, the world is one in which individuals and entities such as institutions or governments only cooperate when they feel there is something to gain. Such a way of thinking is a reminiscent of the understanding of the world during the Cold War, a period in which ‘Realist’ theory predominated. Neorealism can be seen as the evolution of this theory: “Neorealists still claim to be pessimists about human nature, but they seek to move beyond what they understand to be the conceptually vague notion of human nature” (ibid.). If a government cannot take any advantage out of international cooperation, it will not happen. Therefore, cooperation only occurs where national interests are involved. The world is seen as an anarchic environment, in which no value is attached to international institutions and systems. As such, relationships between governments can only take place if such relations are in a government’s national interests. This leads to the commonly accepted outcome of a world in which there is a conflict of power. “Neo-realism: modification of the realist approach, by recognizing economic resources (in addition to military capabilities) are a basis for exercising influence” (Baylis, et al, 2011, p.570). Neorealism portrays any given government as an aggressive entity as they use their military and economic power over other stats.

The third and main theory for this paper is the concept Normative Power (Baylis et al, 2011, chapter 11). Unlike the other two theories, it is not a school of thought. It is a concept which is part of Constructivism, and is used as it forms part of international relations. The school of thought of Constructivism is considered as upholding the ideals of human consciousness. It is a meant to stress idealist understanding and holistic structures (Baylis et al, 2011, p.561). However, for the purposes of this case study, it was decided to only use the concept of normative power from constructivism.

As Manners (2002, p.239) points out: “The concept of normative power is an attempt to refocus analysis away from the empirical emphasis on the EU’s institutions or policies, and towards including cognitive process, with both substantive and symbolic components”. While it is true that this quote is focused on the European perspective, it, nonetheless, offers a clear definition of normative power. It shows that normative power is the ‘power over opinion’, and a means of exporting values and norms by decisions, which are made and followed beyond just simple meetings (ibid.). It draws attention to the “internationalization norms” that a country exports towards another country (Baylis et al, 2011, p.161). When looking at the relationships between the UK, France and Libya, it is true that the theory of normative power may not appear to be related. The means used for international relations is mainly military. However, the case can be made that the intervention of the two European countries is motivated by their respective values and norms as they relate to events in Libya.

In the second chapter, further clarity is offered to demonstrate that neither Neoliberalism nor Neorealism match the case study. This is because bombarding Libya is not related to welfare profit or a contribution to the balance of powers in the world. By the fact that it is a UN decree to attack the military compounds of Gaddafi’s army, it is a lone state’s action as it would be expected in Neorealism, nor a minority, in the sense of elitism and experts. It is a joint decision between governments and civil powers in the UN that highlighted the urgency of actions (Security Council, 2011).

Decision Makers in the Coalition

The first criterion out of the three proposed, is: ‘Decision makers’. The aim is to identify the people and/or organizations that are in command. In other words, each theory looks for distinctive decision makers. Attempting to find who the decision makers in this conflict with Libya are, is the first step to answer the research question.

More than a definition of normative power is needed to identify the decision makers. The scholar Youngs (2004, p.420), offers a clear examination of the criterion of decision makers or ‘actors’:

The stated aim of this work [to export values and norms] has been to highlight the genuine co-constitution of governmental and civil-society actors, within reflective ‘spirals’ of mutual conditioning. In practice, research has focused on how international NGOs succeed in getting normative policies adopted at the government level, with governments then more positively coming to see their own identity and interests in terms of respect for human rights norms.

He argues that the Decision makers are the state, governmental officials and any other civil actors, including NGOs; actors from a normative power’s point of view.

Motivation for a coalition between France and UK

The second criterion is ‘Motivation for a coalition between France and UK’. The three theories and their review demonstrate that each have a different purpose and driver to engage international relations. As a result, the motivations behind the actions of each decision maker, differs as well.

For Normative Power, the motivation for a coalition depicts the imposition of the values and conventions of one country over another by using soft power. “It has become commonplace to suggest that value-oriented policies have both flowed from and served to reinforce the EU’s own identity by purporting to externalize key tenets that, it is contended, define the very essence of the integration project. Talking about values externally can be seen as one factor contributing to efforts to strengthen their vitality internally. (ibid., p.419). Even though Youngs focuses on the case of the EU, the fundamental argument can be applied from any other angle: the motivation for external relations is to enhance a country’s own legitimacy, in this case to EU key players, France and UK.

Objectives of the coalition

Decision makers are identified, motivation for the coalition has been demonstrated, but the overall objective remained unclear for now. The understanding of the common objectives of the coalition aims to offer clarity as to which theory best applies in this case.

Thus, the concept of normative power is “to defend and export the home country’s values and norms” through international cooperation (Dorer et al, 2011, p.6). As such, the coalition of France and the UK came to existence to export and defend their values and norms under the terms of Normative Power

To summarize the theoretical framework

The three criteria have revisited by applying normative theory lens. To demonstrate that the intervention of France and the UK falls under normative power, we have pointed to the power balance between the government and the civil-power for the decision that was taken.

This should fulfil the first criterion, ‘Decision makers’. The second criterion, ‘Motivation for a coalition between France and UK’, again from a Normative Power’s point of view, it is to boost one’s own legitimacy. The third criterion titled ‘Objectives of the coalition’; the personal and/or organization that the decision makers represent must attempt to export their values and upholding them. Defining the three criteria as above allows us to evaluate the applicability of the theories in realistic situations and contexts. From an academic understanding, the case study offers insight into the reasoning used by France and the UK to intervene in Libya.

II. The ‘no-fly zone’ mandate

This chapter will investigate the three criteria described above, and apply them against reality. It is sub-divided into three sections. Unlike Whang (2010) or Hage (2011), this paper did not attempt to analyze the political field and its implication from a theoretical mathematical perspective. Yet, it does agree with the fact that “the similarity of states’ foreign policy position is a standard variable in the quantitative, dyadic analysis of international relations” (Hage, 2011, p.1). The first section looks at who is responsible, and is named ‘Decision makers’ in accordance with the first criterion. Next follows a section focusing on the nature of the international cooperation to intervene in Libya, looking at reasons why the actors became involved, named ‘Motivation for a coalition between France and UK’. The final section will shed light on the main aim that the decision makers wish to accomplish, and is named ‘Objectives of the coalition’.

Decision makers in the Coalition

On March 19th 2011, the United Nation Security Council (UNSC) in New York convened a meeting which started at 6:25pm and closed at 7.20pm (Security Council, 2011). During this meeting, a new mandate to intervene in Libya was agreed upon. When discussing of ‘Decision makers’, it is to be seeking the actual people or organization which are responsible. In order to demonstrate who is in command, a clear overview will be provided of what took place during the process of the mandate authorizing military action against Libya. Following this, an analysis of the countries or organizations that took the lead in enforcing the aforementioned mandate will be used to demonstrate the key decision makers in this regard.

The new mandate was to protect against alleged civilian attacks taking place in Libya:

“France had been working assiduously with the United Kingdom, the United States and other members of the international community calling for means to protect the civil population. Those efforts had let to the elaboration of the current resolution, which authorized the Arab League and that Member States wishing to do so to take all the measures to protect the areas that were being threatened by Qadhafi regime” (ibid.).

Already from the beginning, the French and the British were prepared to take action in order to tackle the Libyan crisis. At the end of the long and difficult meeting, Mandate 1970/73 was voted for and passed (ibid.), more commonly known as a ‘no-fly zone’ mandate (Friedman, 2011, p.1). The following quote gives a brief understanding of the mandate: “To create the ‘no-fly’ zone, the Council allowed member states to act ‘nationally or through regional organization […] to take all necessary measure to enforce compliance with the ban on flights’” (Prashad, 2011). The phrase ‘all necessary measures’ is the most significant part. It enables any country taking part in enforcing the mandate to use military or other means to ensure the goal of the mandate (ibid.). In a press conference with officials of the UK army, they reasoned that the use of armed forces was necessary due to their mission: “What the UN has authorized is a no-fly zone and ‘all necessary measures’ to protect civilians” (UK Ministry of Defence, March 2011).

However, passing the mandate alone was not enough and further action was now required. At this point there is a need to examine who took the action and what reporting requirements did those actors have? France and the United States, closely followed by the UK, took immediate military action in order to enforce the UNSC mandate: “The UK prime minister later confirmed British planes were also in action, while US had fired its first Cruise missiles. […] The French plane fired the first shot in Libya at 1645 GMT and destroyed its target, according to a military spokesman” (BBC News, March 19th, 2011). By flexing their military muscles at such an early stage, France, the UK and the USA constituted the main actors in the intervention. “This operation is currently under the US command with high-profile France and UK involvement, as well as close co-ordination with a range of other countries, including Arab states” (UK Ministry of Defence, March 2011). This means that the heads of these countries (the Presidents of France and the USA and the Prime Minister of the UK) were the key decision-makers. There is no clear proof of civilian involvement in the action besides the freezing of some assets of Gaddafi (Security Council, 2011). However, the countries would have not been able to legitimize their actions without the UN consent which “provided the legal basis for [the enforcement of the ‘no-fly’ zone] action” (UK Ministry of Defence, March 2011).

Motivation for a coalition between France and UK

Whenever a country decides to take international action, it is usually not based on altruistic. As mentioned above, this subchapter investigates exactly what motivated the coalition of France and the UK to enforce the UNSC mandate 1970/73. Investigation points to two main reasons. The first one is a question of using direct military action to maintain the balance of power. The second argues that the coalition is only intervening in order to gain economic advantage through control of some share of Libyan oil.

Few efforts for a diplomatic solution between the foreign powers and Gaddafi’s regime were made. As Marwan Bishara (MB) highlighted on his show entitled ‘Empire’ on the Aljazeera television station in May 2011: “MB: [T]hen Europe got involved and France, in particular, rushed to war. Not even any serious attempt at diplomacy” (Bishara, May 2011). He goes on to say that this attitude was unusual, since usually “you give them ultimatum, you do this or we do that. Not even an attempt” (ibid.). However, on the same programme, Alvaro De Vasconcelos (ADV) responded, saying that the situation was urgent because of the threat of a massacre taking place if no immediate action was taken: “ADV: “Benghazi, a city of one million people, and in front of Benghazi, the Gaddafi tanks” (ibid.). This interaction demonstrates the necessity of taking direct military action in order to enforce the ‘no-fly’ zone mandate.

The necessity to enforce the ‘no-fly’ zone meant that countries with strong military capabilities needed to take action. “ADV: It is not Europe that is making the intervention in Libya. […] It is France and Great Britain. […] [T]he two most well-prepared militaries of the European states. And France has this tradition of military intervention” (ibid.). Mr. De Vasconcelos argues that it is not a world or western coalition, rather that it is one of all the important historical military countries of the western world, especially in Europe, that took the initiative to protect civilians from the threat to their lives that may have occurred. To a certain extent, this demonstrates an action taken to enforce the balance of power. Regarding the national security of France, it is written: “Today threats and natural risks have taken on a global dimension: war, proliferation, terrorism […]. All of these threats must be faced by an effective and legitimate international security system. France considers, therefore, that it is essential to reinforce international institutions to act in favour of peace and international security” (French Defence and National Security, 2008). The UK can be seen as adopting a similar position on foreign policy, evidenced by an article published by Herald de Paris on the national security of the UK in 2010: “The strategy highlights clear national security priorities: counter terrorism, cyber security, international military crisis” (Herald de Paris, October 18th, 2010). These national guidelines for international action and cooperation legitimize the position of power held by France in relation to other countries. Moreover, it credits France with offering support and legitimacy to international and supranational organizations such as the United Nation.

However, some argue that the reason for intervening in the civil war in Libya is due to economic reasons. “The historical record clearly establishes that an external regime change intervention based on mixed motives – even when accompanied with claims of humanitarianism – usually privileges the strategic and economic interests of intervener” (Abu-Rish & Bali, 2011). This quote shows that national interests rather than a good-hearted intention to assist the Libyan people may be behind the action taken in Libya. This opinion is supported by the views of Marwan Bishara on the Aljazeera television show ‘Empire’, who questioned whether the intervention was motivated by economic profit: “MB: The man they want to get rid of was until recently the man they were propping up. You see Muammar Gaddafi has long been portrayed in the west as an erratic eccentric oddball. But when you take a closer look at Britain’s own policy towards Libya, factor in vast commercial interests and a huge dose of crude oil, well it takes eccentricity to a whole new level” (Bishara, May 2011).

At present, however, as many articles and sources demonstrate, one reason for not adopting this viewpoint is that the mandate does not allow any foreign occupation of Libyan land: “Lebanon’s speaker stresses that the [Mandate 1970/73] would not result in the occupation of ‘one inch’ of Libyan territory by foreign forces” (Security Council, 2011). Nonetheless, it is possible to give credit to the economic motivation theory if it is taken into account that part of the duties of foreign forces is to ensure that there is little to no disturbance to oil production which could impact the world economy, however it is perceived as a weak argument overall: “Granted, the world can cope with a disruption of exports from Libya. But what has brought us to $100-a-barrel oil again – and set people on the edge – is the possibility that the uprising that toppled autocrats in Egypt and Tunisia might spread to other OPEC nations in the Middle East” (Mouawad & Krauss, February 2011). This quote demonstrates that the intervention in Libya could be an attempt to ensure that the current disruption taking place does not result in any worst-case scenario in terms of oil supplies. However, it is hard to offer real credit to this theory: “The West had already derived the bulk of Libyan oil contracts […]. Few advantages are able to be gained from the ousting of Gaddafi. What perhaps runs through the DNA of powerful nations is that a protracted civil war in Libya would harm the ability to transit the oil that sits under its soil, and so dangerously harm the ‘way of life’ of those who matter” (Prashad, March 2011). The quote only strengthens the fragility of the argument that economic profit was the main factor in the intervention in Libya’s internal problems.

Objectives of the coalition

Having discussed the decision makers and motivations, the overall goal now needs to be clarified. As such, it is essential to look at two different approaches. The first one discusses the main national goal for taking action in Libya. The second one investigates the main goal that the UNSC agreed upon in Mandate 1970/73. It is not enough just to know who took part and what motivated them to do so, and for this reason this subchapter relating to the aims of the foreign powers in taking action against Gaddafi’s regime represents a primary focus of the paper.

In order to be able to suggest the clear aims of France and the UK, it is necessary to look directly at public statements from the leaders of both countries. Official documents such as national security strategies only shed light on the motivations for actions against Gaddafi’s regime, as demonstrated in the above sub-chapter. The French President Nicolas Sarkozy, declared: “In Libya, the civilian population, which is demanding nothing more than the right to choose their own destiny, is in mortal danger. […] It is our duty to respond to their anguished appeal” (BBC News, March 19th 2011). In this way, the leader of the French nation seems to declare that the objectives of the coalition is to protect the right to freedom of the citizens of Libya. This could be construed as an attempt to export French values and norms to Libya. From a logical perspective, it is hard to believe that the French government is going to act according to values and norms that differ from their national ones. The leaders and associates of the coalition met in Paris in March 2011 and discussed how they would enforce the ‘no-fly’ zone mandate: “French President Nicolas Sarkozy emerged from a meeting of leaders to read the toughly-worded joint declaration. ‘Arab people have chosen to free themselves,’ he said. ‘It is our duty to respond to their anguished appeal’” (Kennedy, March 19th 2011). This demonstrates the coherent position of the nations present, such as the UK, to support the goals declared by the French president.

Throughout the UNSC meeting of March 19, 2011, there are three distinct goals highlighted as the targets of the mandate. The first demands an immediate “ceasefire in Libya, including an end to the current attacks against the civilians” (Security Council, 2011). It is a direct order to Gaddafi’s regime to end their alleged violent containment strategies against their opponents. The second objective of the mandate is to protect the civilians or, to put it in the terms of the official mandate: “to take all necessary measures to protect civilians under threat of attack in the country” (ibid.). The first and second targets of the mandate put any foreign forces enforcing it in a neutral camp which does little more than suppress the military actions of both sides. A third goal is needed in order to assure that the coalition would move against Gaddafi: “[The UNSC] further demanded that Libyan authorities comply with their obligations under international law” (ibid.). Since Gaddafi’s actions essentially constitute an attack on his own civilians, the objective meant that France, the UK and any other associates of the coalition would end up opposing the oppressive regime of Gaddafi.

III. Conclusion

This paper initially developed three criteria and looked at how they are perceived by normative power theories. “Constructing theories according to different suppositions alters the appearance of whole fields of inquiry. A new theory draws attention to new objects of inquiry, interchanges causes and effects, and addresses different world” (Waltz, 1990, p.32). The paper is looking at the facts through the theoretical lenses of normative power in the first chapter. The next chapter was an investigation of the actual meaning of the criteria, which are not based on theoretical fact but instead on real-life actions.

Throughout the development process, the paper has attempted to move towards a favorable position by which to answer to the research question. As such, it is important to assess the criteria one more time and its meanings (See Appendix 1).

The first Criterion is about ‘Decision makers’. With Normative Power, it is essential that the decision making positions are well balanced between Civil Power and Government. The second chapter demonstrated that it was mainly the heads of states, a small minority, which has taken the decisions. Furthermore, they did so through a civil organization: the United Nations (UN). The Second criterion is to boost the Coalition’s legitimacy as ‘Motivation for a coalition between France and UK’. The motivation for a coalition between France and UK was to intervene to protect against the threat of a massacre of civilians. It is against French and UK foreign policy and world position not to take any such action. As such, the analysis suggests that this is one aspect of ensuring a balance of power since to some extend it was an attempt for the two countries to affirm their world military position. Moreover, even though the argument for economic profit as motivation for intervention alone can be seen as weak, in part it was also to ensure that little to no disruption could take place in the world market for oil. In the end, as it is described in the third criterion, as ‘Objectives of the coalition’, it is to export values and to guard them. The final criterion is to protect the civilians, ensure that the international laws are respected and to curb the aggressive action of the Gaddafi’s regime and possibly remove Gaddafi from power.

As demonstrated so far (see Appendix 1), the nature of enforcing Mandate 1970/73 is mainly related to the concept of normative power, indicating that France and the UK are attempting to export their respective norms and values to Libya. As this paper has demonstrated, the foreign policy of France and the UK is a complex mix of different approaches. Through the case study in this paper it can seen that the coalition has adopted a common position. This is due to a combination of different factors. Henceforth, the interests and the choices of France and the UK to act as a union do influence the nature of their foreign policy. As shown in the previous chapter, France and the UK are acting through defending and exporting their norms and values in Libya, whether in regard to the motivations (burden sharing) or to the ultimate goal (shown by statements by each country’s leading figure).

There appears to be no indication that the intervention was an attempt to improve national welfare. However, it could be argued that the intervention was made in an attempt to extend markets through cooperation due to the priority of protecting the Libyan oil supply and preventing its removal from Libya. In respect to Neorealism, one may argue that France and the UK are attempting to improve their position in the world, especially in the Arab world, as demonstrated by the attempts to work with Arabic nations through the creation of the terms of the ‘no-fly’ zone. However, it is questionable if both countries are attempting to do so for their own self-interest as there is no real direct gain from an economic or territorial viewpoint. In fact, the intervention seems to only achieve high expenses for using military weapons and a delicate relationship with the Arab world which to a certain extent did not change much.

In the long term, it can be seen that coalitions created by the UN may become a tool more actively used for humanitarian interventions while respecting the international law. Nonetheless, it may not always include France and UK. With new global powers, a new type of coalition may take place which would not presuppose that it would be in a normative power conditions like the case of this paper.

The paper primary focused on the French and UK perspective, looking at the deliberate choices made concerning the type of policy and instruments used against Libya. It would be interesting to study the role and motivations of the US in the intervention, and to attempt to assess whether the intervention was indeed necessary. Though the reaction of the Gaddafi Regime is mentioned, it is not analyzed separately as an influencing variable. It would thus be of great interest to further research these aspects in light of the findings of this paper.

Bibliography

Adler, E. & Haas, P. (1992). Conclusion: epistemic communities, world order, and the creation of a reflective research program. In: Winter. International Organization [Volume 46 (1), pp. 367-390].

Atwater, M. (1996). Social constructivism : Infusion into the multicultural science education research agenda. In Journal of Research in Science Teaching [Volume 33 , pp. 821–837].

Al Jazeera (March 18th, 2011). Middle East; Implementing the no-fly zone: United Nations Security Council voted in favour of a no-fly zone over Libya. Retrieved April 15th, 2011, from http://english.aljazeera.net/video/middleeast/2011/03/20113187402340926.html

Bali, A. & Abu-Rish, Z. (March 20th, 2011). Opinion: The drawbacks of intervention in Libya. In Al Jazeera. Retrieved March 29th, 2011, from http://english.aljazeera.net/indepth/opinion/2011/03/201132093458329910.html

Baylis, J., Smith, S. & Owens, P. (2011). The Globalization of Word Politics: An introduction to international relations. Fifth Edition. Oxford University Press

BBC News (March 19th, 2011). Libya: French plane fires on military vehicle. Retrieved March 25th, 2011, from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-12795971

Black, I. (February 17th, 2011). Libya’s day of rage met by bullets and loyalists. In The Guardian. Retrieved March 25th, 2011, from http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/feb/17/libya-day-of-rage-unrest

Bishara, M. (May 19th, 2011). Empire: Transcript: Europe and the Arab revolutions. In Al Jazeera.. Retrieved, March 25th, 2011, from http://english.aljazeera.net/programmes/empire/2011/05/201152513943444770.html

Booth, K. (2007). Theory of World Security. Cambridge University Press, New York, USA

Chomsky, N. (1999). Profit over People : Neoliberalism and Global Order. A Seven Stories Press First Edition. New York, USA

Cini, M. & Borragan, N. (2010). European Union Politics. 3rd edition. Oxford University Press, New York, USA

Dorer, L., den Kamp, F., Goffard, C., Geenen, L., & Lohman, P., (2011). EU policies towards China: does the nature matter? An insight into human rights, biodiversity and CO2 emissions in China. Paper presented at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences of Maastricht University blog ‘External Relations of the European Union’, Maastricht, The Netherlands

Dougherty, J. & Pfaltzgraff, R. (1997). Contending Theories of International Relations: A Comprehensive Survey. London, UK.

Elman, M. (1995). The Foreign Policies of Small States : Challenging Neorealism in Its Own Backyard. In British Journal of Political Science [Volume 25, pp. 171-217].

Ernest, P. (1998). Social Constructivism as a Philosophy of Mathematics. In Book Reviews. University of New York Press, USA

French Defence and National Security. (2008). French White Paper on Defence and National Security. France’s official Defence and National Security. Paris, France

Friedman, G. (2011). Libya, the West and the Narrative of Democracy. Afgazad press.

Forde, S. (1995). International Realism and the Science of Politics : Thucydides, Machiavelli, and Neorealism. In International Studies Quartely [pp. 141-160]. University of North Texas

Giroux, H. (2004). The Terror of Neoliberalism : Authoritarianism and the Eclipse of Democracy. Paradigm Publisher, USA

Hage, F. (2011). Choice of Circumstance?Adjusting Measures of Foreign Policy Similarity for Chance Agreement. Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for Political Methodology.

Harvey, D. (2007). A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford University Press

Hacking, I. (1999). The social construction of what?”. President and Fellows of Harvard College, USA

Held, D. (1980). Introduction to critical theory : Horkheimer to Habermas. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, USA

Herald de Paris (October 18th, 2010). National Security Strategy. Retrieved March 25th, 2011 from http://www.heralddeparis.com/national-security-strategy/111631

International The News(March 20th, 2011). France, US, UK launch attacks on Libya. Retrieved April 15th, 2011, from http://www.thenews.com.pk/TodaysPrintDetail.aspx?ID=4743&Cat=13&dt=3/20/2011

Jones, R. (1999). Security, Strategy, and Critical Theory. Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc.

Joseph, S. & NYE, Jr. (1988). Neorealism and Neoliberalism. In Review Articles. Trustees of Princeton University

Keohane, R. (1987). Alliances, Threats, and the Uses of Neoralism. In Book Review : The Origins of Alliances by Stephen M. Walt [pp. 321]. Cornell University Press

Kratochwil, F. (1993). The embarrasment of changes : neo-realism as the science of Realpolitik without politics. In Review of International Studies [Volume 19, pp. 63-80]. British International Studies Association

Krause, K. (1998). Critical Theory and Security Studies : The Research Programme of ‘Critical Security Studies’. In Cooperation and Conflict [Volume 33 pp. 298-333]. SAGE Journals online. Retrieved April 15th, 2011, from http://cac.sagepub.com/content/33/3/298.short

Kukla, A. (1999) Social Constructivism and The Philosophy of Science. Routledege Ed. New York and London

Linklater, A. (2007). Critical theory and world politics : Citizenship, sovereitgnty and humanity. Routledge, New York, USA

Manners, I. (2002). Normative Power Europe: A Contradiction in Terms?. Journal of Common Market Studies [Volume 40 (2), pp .235-258].

Merco Press: South Atlantic News Agency (March 20th, 2011). US, UK and France begin bombing Libyan military targets following UN resolution. Retrieved April 15th, 2011, from http://en.mercopress.com/2011/03/20/us-uk-and-france-begin-bombing-libyan-military-targets-following-un-resolution

Mouawad, J. & Krauss, C. (2011). Tremors from Libya Contribute to Oil Price Cycles. The New York Times Press. Retrieved March 25th, 2011, from http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/28/business/global/28oil.html

Ministry of Defence. (March 19th, 2011). Libya: operation ELLAMY: Questions and Answer. In Defence: factsheet. United Kingdom’s official statement. Retrieved April 19th, 2011, from http://www.mod.uk/DefenceInternet/FactSheets/MilitaryOperations/LibyaOperationEllamyQuestionsAndAnswers.htm

Moravcsik, Andrew (1997) Taking Preferences Seriously: A Liberal Theory of International Politics. In International Organization, [Volume 51 (4), pp. 516-533].

Ong, A. (2006). Neoliberalism as exception : Mutations in Citizenship and Sovereignty. Duke University Press, USA

Prashad, V. (2011) Intervening in Libya. Znet press

Security Council. (2011). Security Council approves ‘no-fly zone’ over Libya, authorizing ‘all necessary measures’ to protect civilians, by vote of 10 in favour with 5 abstentions. In Depanrtment of Public Information. News and Media Division. New York. Retrieved March 29th, 2011, from http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2011/sc10200.doc.htm

Shimko, K. (1992). Realism, Neorealism, and American Liberalism. In The Review of Politics [Volume 54, pp. 281-301]. University of Notre Dame

Stevenson, W. (2007).What’s “Realistic”?. In The realist tradition and contemporary international relations [pp. 51-80]. Louisiana State University Press, USA

Sjursen, H. (2006). The EU as a ‘normative’ power: how can this be? Journal of European Public Policy [Volume 13 (2), 235-251].

The Sunday Times (April 17th, 2011). NATO exceeding Security Council Mandate: Russia. Retrieved March 25th, 2011, from http://sundaytimes.lk/110417/Timestwo/t2_08.html

Touraine, A. (1998). Beyond Neoliberalism. Cambridge, UK

Youngs, R. (2004). Normative Dynamics and Strategic Interests in the EU’s External Identity. In Journal of Common Market [Volume 42 (2), pp.415-435]. University of Portsmouth

Watt, N., Hopkins, N., & Traynor, I. (March 23rd, 2011). Nato to take control in Libya after US, UK and France reach agreement. In The Guardian. Newspaper. Retrieved April 15th, 2011, from http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/mar/22/libya-nato-us-france-uk

Wendt, A.,(1992). Anarchy is What States Make of It: The Social Construction of Power Politics. In International Organization [Volume 46 (1), pp. 391-425].

Whang, T. (2010). Empirical Implications of Signaling Models: Estimation of Belief Updating in International Crisis Bargaining. In Political Analysis [Volume 18, pp. 381-402]. Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for Political Methodology

[1] It is useful to emphasize that this paper does not seek a general theory of international politics. On the contrary, as have Adler and Haas (1992) expanded in their methodology of their article Conclusion: epistemic communities, world order, and the creation of a reflective research program”, this paper will specify a precise number of restrictions through which logic is feasible. A reaction shall take place and based upon it, and collective meaning, to develop a sensible “our methodology and substantive propositions about a reflective research program” (Adler et al. 1992. p.2).

—

Written by: Pierce Noah Sebastian Lohman

Written at: Maastricht University, Faculty of Art and Social Sciences

Written for: Bachelor Paper 1

Date written: January – June 2011

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Obama and ‘Learning’ in Foreign Policy: Military Intervention in Libya and Syria

- Egypt’s Security Paradox in Libya

- To What Extent Was the NATO Intervention in Libya a Humanitarian Intervention?

- The Limitations and Capabilities of the United Nations in Modern Conflict

- A Critical Analysis of Libya’s State-Building Challenges Post-Revolution

- Climate Security in the United States and Australia: A Human Security Critique