Introduction

A curious dichotomy has emerged between the casualty patterns amongst Coalition counterinsurgent forces in Iraq during Operation Iraqi Freedom and the overwhelmingly American NATO force (ISAF) in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom. While Iraqi Freedom witnessed a four year plateau in 2004-7 of heavy Coalition casualties in both absolute and relative terms (casualties proportional to the number of COIN troops in the theatre of operations, a crucial distinction for my argument) before Coalition casualties declined precipitously to almost residual levels prior to and since America’s formal withdrawal from Iraq, Enduring Freedom has witnessed a dramatic increase in ISAF casualties since 2006-7[1]. How can we explain this divergence?

The disparity in relative casualty trajectories naturally generates explanations focusing on the structural differences between these globalised insurgencies. These differences can roughly be grouped as both endogenous (unique conditions on the ground) and exogenous (the outside, transnational factors affecting COIN efforts, particularly the zeitgeist of US policymaking in the mid-2000s), although substantial interrelation exists. Endogenously, “the insurgency” in Iraq comprised a hodgepodge of ethnically heterogeneous anti-American groups resisting the overwhelmingly American occupation in the urban wilderness (providing US forces with a host of enemy insurgent networks to confront). In Afghanistan, the more homogenously Pashtun (and to a lesser extent Sunni Arab) and rural Taliban/al Qaeda insurgency has made extensive use of the country’s rugged terrain to regroup after Enduring Freedom’s initial onslaught. Critically, this regrouping period was made possible by the externally influenced American decision to devote an overwhelming proportion of its resources to Iraq during the early years of Enduring Freedom, turning Afghanistan into a virtual afterthought until the Taliban began to inflict mounting damage on American forces.

While the above contention possesses an element of truth, I will argue that counterinsurgent casualty rates extend beyond a reflection of the structure of the insurgencies and by extension the COIN effort. Instead, I will argue that Western counterinsurgent casualty rates in Iraq and Afghanistan relative to the number of Western troops in the theatre of operations are epiphenomenal of insurgent success, with higher Western casualties indicative of greater insurgent progress in undermining governmental legitimacy and security. I use the modifier “relative” to dissociate absolute casualty numbers and insurgent triumph, for America’s successful “surge” in 2007 (vis-à-vis promoting Iraqi governmental legitimacy and security) amidst high absolute losses disproves the absolute/insurgent triumph connection. However, the contention that COIN casualty rates are a function of insurgent success raises an ancillary question: Why has the Iraqi insurgency largely dissipated since mid-2007, while the Taliban insurgency has steadily escalated since the end of 2006?

I plan to explain the disparate trajectories of casualties/insurgent success within these globalised insurgencies through a combination of small-n comparison between Iraq and Afghanistan, comparative historical sociology, and Mill’s Method of Difference. To begin my theoretical analysis, I will disaggregate the “insurgent” and “globalised” elements comprising internal conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan. First, I will explicate the conventional, qualitative barometers of insurgent success: tactical innovation derived from strategic interaction; subsequent institutional capacity for learning; and the culminating determinant of insurgent success, the ensuing popular perceptions of physical security and governmental legitimacy.

Next, I will build upon this foundation by situating Western counterinsurgency casualty patterns within comparative theories of “new war” and “new terror,” two paradigms of global conflict which find a synthesis through my examination of globalised insurgency. This section marks a crucial departure from the pre-globalised concepts of insurgent success introduced earlier, illustrating the feedback loops and unforeseen externalities whose ramifications extend far beyond a particular country. Indeed, I will argue that the Western ability (or lack thereof) to disrupt the feedback loop between the local innovations of insurgents employing “new terror” tactics and the globalised, external influxes of combatants, ideas, resources, and other inputs central to “new war” is the primary causal mechanism for determining insurgent success.

While the networks which held together Iraq’s feedback loop attenuated and were largely eradicated through population control, the Taliban’s durability in recent years is a direct product of the stout links within and across networks undertaking the new war and new terror methods of globalised insurgency which are more resistant to population control. These networks prove hardier than their Iraqi counterparts due to their grounding in 1) increasing dissatisfaction with the Afghan government (leading to decreased popular participation in the government) while the Iraqi feedback loops weakened with increased popular satisfaction with government security capabilities and 2) long-standing, pre-globalisation interpersonal connections, a stronger foundation than the globalisation-era marriages of convenience which underpinned the Iraqi insurgent networks. Finally, I will discuss the ramifications of my findings for on-going and future insurgencies from the perspective of comparative political scholars, Western policymakers, and Western public opinion.

Barometers for Insurgent Success

A: Insurgency—Strategic Interaction and Tactical Innovation

The simple military interaction between insurgents and counterinsurgents provides but a fraction of their interface. Instead their interaction resides in the non-kinetic sphere of local histories and contexts. These preconditions for strategic interaction heavily favour the overwhelmingly home-grown insurgent, creating a dynamic of perpetual tactical catch-up by COIN forces. The theoretical literature on the subject underscores this uneven playing field. As Charles Tilly notes, the evolving repertoire of tactics and behaviours within collective action is deeply rooted in indigenous culture and structures,[2] precluding all but the most transient understanding of the environment by outside counterinsurgents[3]. Indeed, the sheer volume of provincial information necessary to process perpetually overwhelms counterinsurgents, who lean on their institutional expertise and resort to heavy-handed military solutions, a response which exacerbates local instability[4].

The disconnect between the intensely parochial nature of civil war (insurgency comprises a subset of civil war) and the centralised struggle of counterinsurgents to create a viable and legitimate national government further disadvantages counterinsurgent forces. Kalyvas’ trenchant observation that civil wars are “welters of complex struggles” rather than the simple binary conflicts espoused in the master narrative of counterinsurgency (pro-government vs. anti-government)[5] illustrates the fundamental gap in understanding between insurgents and counterinsurgents about the enemy they are fighting. This disjuncture undermines the capacity for counterinsurgents to adapt to insurgent tactics and innovation, a critical disadvantage in the battle to best provide security to the local population.

Beyond the advantageous local conditions, successful insurgent movements do not require the coordination and cooperation essential for a viable COIN effort. In game-theoretic terms, insurgents have the clarity of playing a pure conflict game against counterinsurgents to attain their goals, while the COIN apparatus—external military forces, civilian organisations, and local government—must play a cooperation game predicated on a convergent interest which rarely exists amongst disparate and unaffiliated institutions[6].

Despite the seemingly unfettered options available to insurgents operating under pure conflict conditions, the large array of actors within an insurgency complicates the strategic interaction between insurgents and counterinsurgents, with the fluidity of roles amongst both insurgents and counterinsurgents moulding and constraining the tactics and innovations of both sides. As Mia Bloom points out, the insurgent’s community provides the material, support, and hospitable environment necessary to survive. Accordingly, insurgency organisations must make cost/benefit analyses of their variety of tactics to prevent the community shifting from active collaborator to uninvolved or even actively opposed to the insurgency[7]. However, the converse applies to COIN methods, where most of the counterinsurgents’ traditional tactics are prone to alienating an otherwise sympathetic population[8] as well as generating support for the insurgency from external audiences. These conditions inherently limit the military options available to contemporary counterinsurgents far more than the strictures placed on insurgents[9].

The combination of local hindrances and the need for coordinated yet circumspect COIN tactics creates a reactive strategic environment for counterinsurgents, for insurgents perpetually possess the tactical initiative. Accordingly, tactical innovation and creativity originate with insurgents, who initiate the cycle of method and counter-method whereby a tool or technique’s effectiveness is reduced by countermeasures, then refined to bypass the countermeasures and so on[10]. However, counterinsurgents seek victory not through the Sisyphean task of playing catch-up with insurgent innovations, but through adapting their extant means and methods[11]. As the philosophical architect for US COIN David Kilcullen put it, “COIN is at heart an adaptation battle: a struggle to rapidly develop and learn new techniques and apply them before the enemy can evolve in response”[12]. Nonetheless, in this adaptation battle the counterinsurgents must fight on unfamiliar and unfavourable terrain, with every lesson coming at a heavy cost in COIN casualties[13].

B: Insurgency—Institutional Capacity for Learning

The ability to implement country-wide tactical innovation illustrates a broader capacity for institutional learning amongst the military organisations of insurgents and counterinsurgents, with accreted local wisdom filtering upwards as informal knowledge mixes with formalised doctrine to create a coherent military strategy. This intermingling of informal conduct and routinized behaviour frequently provides initial advantages to insurgents. Institutional learning amongst counterinsurgents must proceed by processing informal learning through the organisation’s extant systems for education[14], with a lag period built into any institutional understanding of an insurgency due to every insurgency’s inherent uniqueness[15]. Moreover, as highly hierarchical and formalised institutions, Western militaries tend to possess a degree of centralisation negatively associated with innovativeness, with a deep-seated devotion to traditional operating procedures[16]. For example, US Army doctrine during Vietnam paid little attention to fighting unconventional warfare against an insurgency due to an entrenched emphasis on fighting set-piece battles against a conventional military force. Accordingly, all informal learning was processed through a formalised system of increasing the effectiveness of US firepower, stifling continuing innovation at the local level and precluding any understanding about the true nature of the enemy and the means to defeat them[17].

Conversely, insurgent organisations acquire greater structure and formality only over time in keeping with the bureaucratisation of social movements[18], removing the initial barriers to the quick dissemination of institutional learning. However, like their COIN counterparts, insurgents also possess ideological constraints to their capacity for institutional learning, with group ambitions determining an insurgency’s core objectives and the means by which these objectives are to be achieved[19].

Despite possessing similar doctrinal constraints, insurgent institutions have an accelerated learning curve due to the accessibility of the “demonstration effect.” As both Martha Crenshaw and Bloom note, insurgent organisations which employ terroristic tactics quickly become familiar with what has worked and what has failed in other circumstances[20], providing strategic templates unavailable to counterinsurgents due to the context-specific undertaking of COIN[21]. In addition, the well-documented operational procedures of Western military forces provides a clear picture for insurgents of the enemy they are facing, whereas counterinsurgents must overcome the fog of war to ascertain the character and composition of an insurgency. Accordingly, insurgents’ local advantages permeate into the broader strategic landscape of an internal war, hamstringing COIN efforts to conceptualize the challenge to their authority and implement a better alternative.

C: Popular Perceptions of Security and Governmental Legitimacy

Despite the importance of strategic interaction and institutional learning, they simply provide interrelated indicators at the local and national level respectively for popular perceptions of security and governmental legitimacy, the ultimate barometer for a successful COIN effort due to the overarching importance of the population in insurgency[22]. As Kalyvas notes, at the local level collaboration with COIN forces vary with perceptions that counterinsurgents are prevailing over the home-grown insurgents (a difficult task as a result of the aforementioned local advantages afforded to insurgents) and thus abler at providing security and maximizing chances of survival amidst the profusion of localised struggles occurring during civil war[23]. The provision of security to the native population—euphemistically known as “winning hearts and minds”—entails counterinsurgents imposing their control over an area to create predictability and normalcy in the authorities’ conduct.

To paraphrase Kilcullen, COIN tactical success stems from establishing an enduring local presence regulating people’s actions through a normative system of rules and sanctions[24], mitigating fears instead of winning any grand ideological battle. Indeed, counterinsurgents’ introduction of local security forces, political reform, and economic benefits in hopes of creating a “trickle-down” effect and gaining an immediate ideological victory to win over the community ignores how the insurgents themselves constitute a significant part of the community, a myopic approach which ignores the need for gradualist governmental and ideological formation and generally results in a protracted insurgency[25].

Thus, at the strategic and nation-wide level, the establishment of a Weberian monopoly on force is a necessary but insufficient condition for COIN success. The insurgents know that their enemy will eventually leave while they will remain, a “longevity advantage” which necessitates that counterinsurgents build an inclusive and predictable government apparatus capable of withstanding insurgent claims to governance[26]. Just as the amalgamation of tactical innovations proves critical to broader institutional learning and capacity to create a coherent strategic doctrine, the long-term construction of local governmental administration and political consolidation is essential to a greater COIN ideological coherence in refuting the various insurgent (and consequently indigenous) bids for governmental legitimacy[27].

Consequently, the military serves as the literal and metaphorical spearhead for any COIN effort, with the administrative apparatus following in its wake. In the “clear, hold, and build” model for COIN espoused by Kilcullen, Hammes, and other COIN scholars, the military must clear and hold territory to make it pliable for imposing a government which the population recognises as most capable of ensuring its security. The difficulty in extricating insurgents from their own communities necessitates large expenditures of blood and treasure amongst counterinsurgents, creating a kaleidoscopic strategic landscape which has only become more confusing for counterinsurgents in the age of the globalised insurgency.

COIN Casualties and the New War/Terror Nexus in Globalised Insurgency

In this section of the work, I will situate the insurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan within Mary Kaldor’s theory of “new war” and the similar yet distinct comparative theory of “new terror” to link the aforementioned classical aspects of insurgency present in Iraq and Afghanistan with the unique aspects of 21st century insurgency, an evolution stemming from the impact of globalisation. Within this coalescence of old and new, I will demonstrate how COIN casualties assume new-found importance as harbingers of larger trends as well as an instrumental significance in its own right, an essential understanding for the correlation between insurgent success and US casualty figures in Iraq and Afghanistan.

A: New War, Globalised Insurgency, and COIN Casualties

Mary Kaldor’s “New and Old Wars” posits that a fundamental schism exists between Cold War-era civil wars and their post-war descendants, with the torrential pace of globalisation accountable for the erosion of the Weberian state during “new wars”[28]. According to Kaldor, a revolution in military affairs has transpired in the social relations of warfare, with previously localised civil conflicts assuming a transnational character (due to global interconnectedness) which blur jus in bello considerations of legitimate use of force as particularist, ascriptive identities become the dominant cleavage between political actors[29]. In a similar vein, Paul Gilbert views new war as a product of identity politics, with (frequently transnational) groups formed around collective identities contesting values instead of any state-based objective such as territory[30].

Based on a synthesis of these ideas, Kaldor and Gilbert seek to cast off the overarching ideological premises of Cold War-era civil war[31] to create a paradigm of war centred on the free-for-all of a world ill-equipped to handle the rapid change of globalisation. However, as renowned sociologist Marcel Mauss observed war is an all-encompassing social phenomenon. Accordingly, to analyse the merits of new war’s variation from classical insurgency (and the consequent ramifications for the import of COIN casualties) one must gauge how much globalisation has altered the world we live in. Is it the revolutionised security environment implied by Kaldor, or the world envisioned by new war detractors such as Kalyvas, where continuities far outweigh new developments?

The swift diffusion of the intangible (information, ideas) and tangible (people, things) made possible by globalisation’s rapid improvements in communications and transportation has undeniably altered the security environment confronting counterinsurgents, creating a far hazier distinction between local actor and external supporter than seen in “old” wars. In this new iteration of warfare, insurgencies now seek to transcend the parochial aspects of their struggle, tailoring their strategic doctrine to match the interests and agendas of distant audiences instead of prioritising sustenance from the local community[32].

Furthermore, the post-Cold War insurgent operational doctrine underscores the potentially superfluous nature of the state in modern civil warfare, an unprecedented phenomenon. For instance, while modern insurgents do conventional fundraising, they also run private charity organisations, businesses, and criminal enterprises to finance their campaigns. By contrast, most classical insurgencies depended overwhelmingly on one or two major sponsors, which counterinsurgents could subject to diplomatic or economic pressure[33]. As contemporary COIN scholars such as Kilcullen recognise, this new, globalised insurgency demands a rethink of traditional COIN, with the application of 1960s techniques transformed to include international counterterrorism strategies[34] to handle a threat which transcends the borders of Iraq and Afghanistan, an assessment directly in line with Kaldor’s claims.

Despite the significant changes wrought on insurgents’ strategic operating principles by globalisation, the sheer volume of commonalities between Cold War-era and post-Cold War insurgencies renders the revolution trumpeted by Kaldor and other new war theorists merely an evolution for counterinsurgent strategists. Critically, the privatisation of war cited by new war theorists—where state actors can be circumvented by non-state actors as the primary contestants in an insurgency—implies insurgencies can avoid the state-level politics of popular legitimacy inherent within the public sphere by ruling simply through a programme of “fear and hatred”[35], an assertion unsupported on theoretical or empirical grounds. As Kalyvas discovered in his exhaustive study of insurgencies and civil conflicts preceding and following the Cold War, insurgencies remained a competition for government where the outcome was established by penetrating society and regulating people’s actions through a normative system of rules and sanctions. These structures create predictability and order, establishing a presence that causes people to feel safe and makes them flock to your side[36]—in short, a fundamentally political contest for popular legitimacy at the state level stemming from aggregations of locally recognised authority.

Moreover, pragmatic considerations matter more in internal conflict than the values-based judgments presumed by new war theorists such as Kaldor and Gilbert[37], with local support following the stronger side in the insurgency[38]. Although globalisation has altered the guiding strategic principles for insurgents in the post-Cold War era, the core strategic philosophy amongst counterinsurgents—that insurgency is a political competition between insurgents and counterinsurgents for governance based on an amalgamation of localised conflicts between the two sides—remain in place to shape the operating principles for counterinsurgents, a dichotomy which has created major implications for COIN casualties in the age of the globalised insurgency.

The disjuncture between globalisation’s impact on insurgent and counterinsurgent strategic doctrine has made COIN casualties matter differently for each side’s notions of progress and success. For insurgents, COIN casualties directly amplify and validate the worthiness of their efforts amidst both the global and local audience. The reporting of COIN casualties in the global media enables a diffusion of consciousness-raising amongst external onlookers, permitting insurgents to market themselves and their causes[39]. At the local level, COIN casualties demonstrate to the uncommitted members of the resident population that the insurgents possess a mobilized and potent support base amongst the population, leaving the counterinsurgents unable to protect themselves, let alone the native community[40].

Conversely, COIN casualties possess a more indirect impact for the counterinsurgents beyond the obvious costs in blood and treasure, although the ancillary setback for the COIN effort redounds to the insurgent’s aforementioned advantages. As Feaver, Gelpi, and Reifler discovered, amongst Western publics the tolerance for enduring casualties depends on beliefs about whether the United States was right to become involved in combat and whether or not the operations are likely to succeed instead of casualty totals, with rising casualties affecting public opinion only as a function of reshaping the outlooks on the likelihood of COIN success[41]. Instead, as mentioned earlier COIN casualties embody a lesson learned in the unceasing struggle for counterinsurgents to adapt to local conditions and the broader strategic environment[42]. Thus, compared to the zero-sum nature of COIN casualties in classical insurgency, COIN casualties in globalised insurgency not only subtract from the COIN effort but multiply instead of merely add to the utility of insurgent operations, giving COIN casualties far greater import than initially meets the eye.

B: New Terror, Globalised Insurgency, and COIN Casualties

While new war theory focuses on a more holistic overview of the strategic landscape, the “new terror” espoused by globalisation scholars such as Niranjan Dass, Adrian Guelke, and David Martin Jones emphasises the operational aspects of globalised insurgency, where terroristic methods designed for global shock value such as suicide bombing coincide with more conventional insurgent tactics. In particular, new terror scholars extend Kaldor et al’s de-emphasis of state combatants within a civil conflict by highlighting the role of tactically autonomous and decentralised networks perpetrating attacks on COIN forces and other targets[43].

These networks extend from the interpersonal realm to the technological arena, a phenomenon encapsulated by the new terror concept of “netwar.” According to David Martin Jones, netwar involves “measures short of traditional war, in which the protagonists are likely to consist of dispersed, small groups who communicate, coordinate, and conduct their campaigns in an inter-netted manner, without a precise central command[44],” tantamount to undertaking new war at the micro-level. Similar to new war’s impact on insurgent strategy (and the more residual impact on counterinsurgents’ need to continually adapt), the confluence of new terror’s transformations of insurgent structure, operating procedures, and arsenal of new tactical choices have transformed the tactical landscape for insurgents. In particular, new terror has compounded the salience of COIN casualties for determining insurgent success in the age of the globalised insurgency.

New terror has provided insurgents with a template for asymmetric warfare in the globalised era, mitigating counterinsurgents’ vast superiorities in resources and technical sophistication by employing globalised technologies to orchestrate insurgency logistics and operations as well as terror attacks by exogenous organisations. With a geographical and temporal diffusion of networks, new terror has enabled coordinated as well as autonomous tactics amongst insurgents and their terrorist allies. As Niranjan Dass observed, the emergence of globalised technologies such as the Internet has substantially increased the scope and complexity of the information that can be shared, allowing participants to have rich exchanges about their common foe without requiring them to be located in close proximity[45].

Accordingly, while insurgencies inherently rely upon asymmetric warfare to counteract their conventional inferiority, the establishment of dispersed and self-sufficient networks to carry out attacks have made it highly difficult for Western COIN forces to comprehensively confront an insurgency[46]. With the advent of new terror, “insurgency” now provides a blanket label to all these networks contesting the external imposition of a new government. Thus, the networks’ disparate ideological underpinnings (and by extension their operating procedures and choice of tactics) obstruct the construction of a comprehensive tactical approach by counterinsurgents to ameliorate the already-steep learning curve, underscoring the multiplier effect in the insurgents’ favour seen in the broader tableau of new war[47].

New terror’s capacity for quick dissemination of tactics and information across networks has amplified the potency of tactics employed by insurgents and terrorists alike against COIN forces and the local population, particularly the potency of the bombing attack. Although the use of bombs themselves demonstrates a measure of tactical conservativeness, globalisation has enhanced the sophistication of bomb-making to offset the lack of novelty, with transportation advances enhancing the reach of new terror bombing throughout a polity[48]. As alluded to in new war’s capacity for raising external consciousness at the broader, more abstract level, new terror’s particularly lethal tactics allow the perpetrators an easy means of gaining attention for their personal network/agenda, with the Internet offering far more direct control of the network’s message to the public[49]. On the COIN side, counterinsurgents have had to counter the tactical intelligence accruing amongst insurgents through the painstaking dismantling of insurgent/terrorist networks, a resource-intensive process which also yields an inordinate amount of human and financial costs[50].

Taken together, new war and new terror’s refashioning of contemporary insurgency in the age of globalisation blends the external inputs of networked resources and personnel into the contested polity with the internal outputs of propaganda via attacks on COIN forces and their governmental allies and the subsequent COIN response. This dynamic feedback loop has moulded the contours of the insurgency in Iraq and Afghanistan, with US COIN progress (or lack thereof) in establishing the legitimacy of the Iraqi and Afghan governments directly relating to the American military’s ability to tactically adapt and learn as an institution about the intricacies of globalised insurgency.

Section 4: Empirical Analyses of the Iraq and Afghanistan Insurgencies

To reiterate my argument outlined in the Introduction, I hope to demonstrate that the divergent Western casualty patterns in the Iraq and Afghanistan insurgencies are a direct function of insurgent success in controlling the local population and undermining the incumbent government’s legitimacy while promulgating their own governance across the polity in their respective conflicts. The causal mechanism for insurgent success derives from the Western ability (or lack thereof) to disrupt the feedback loop between the local innovations of insurgents employing “new terror” tactics and the globalised, external influxes of combatants, ideas, resources, and other inputs central to “new war.” This feedback loop generates self-perpetuating and fast-paced tactical innovation and institutional learning within and across insurgent networks, infusing any understanding of conventional barometers of insurgent progress.

Most importantly, the continued viability of the new war/terror feedback loop casts doubt on popular perceptions of governmental legitimacy and ability to provide local security. Accordingly, the examination of the qualified success of Coalition forces in Iraq will illustrate the severe disruption of the new war/new terror feedback loop through classical COIN methods of population control to interrupt the interpersonal flow of networked ideas and resources within and across groups, reducing Coalition casualties precipitously. Conversely, the Afghanistan section will highlight how the failure of ISAF forces to control networks amongst the Afghan population (both on the borders and within populated areas) has led to minimal disruption of the new war/new terror feedback loop in recent years, allowing the insurgency to expand and generating a ballooning of ISAF fatalities.

A: Iraq—Rise and Fall of Coalition Casualties

A brief historical overview of the Iraq counterinsurgency illustrates a strong correspondence between Coalition casualty figures (relative to troop numbers) and the success of Coalition forces in providing local security and transferring authority to a legitimate Iraqi government. Although the Iraqi insurgency developed slowly in mid-2003 as the “honeymoon period” for Coalition forces gradually receded, from 2004-2006 the Iraqi insurgency claimed an average of 2 Coalition deaths a day from hostile-related causes[51]. These figures mirror Iraq’s broader security and legitimacy woes symptomatic of the nexus between new war and new terror: rampant suicide terror attacks against Iraqi governmental forces and civilians, sectarian strife, and widespread lack of participation in the transitional Iraqi government as shadow governments amongst networks of both Sunni insurgents and Shi’a militias across Iraq[52].

However, following a bloody April-May 2007 in the wake of the US “surge” in troops, Coalition casualties dramatically subsided to 14 for the month of December 2007, the lowest total since February 2004[53]. Concurrently, security across Iraq improved dramatically as the increased US troop presence applied its newfound strength and institutional knowledge of COIN (epitomised in the US Army’s new Field Manual 3-24 or FM 3-24), paving the way for the US’ formal handover of security to the Iraqi government in 2009[54]. In short, the broad pattern of COIN casualties in Iraq tells two stories: 1) the actualisation of new war and new terror’s full potential for subverting the state by insurgents from 2004-6 (and consequently impacting conventional barometers for insurgent success) and 2) the opposite effect of institutional learning amongst counterinsurgents on mitigating the influence of the new terror/new war loop, enabling the US-led Coalition to snatch success—albeit a qualified one—from the jaws of failure in Iraq.

New War in Iraq and the Escalation of COIN Casualties

The initial success enjoyed by Sunni insurgents from 2004-2006 (and to a lesser extent in the latter half of 2003 and early months of 2007) stemmed from a stark divide between insurgents and counterinsurgents in their cognisance and learning of the full import of globalised insurgency, a concept inextricably wedded to new war. On the insurgent side, Sunni insurrectionists took full advantage of their ascriptive ties to Salafist communities within Fallujah and the broader Gulf to establish a base of operations in the city in 2004.

Bolstered by inflows of funding from non-state entities such as regional charities and local merchants and a steady stream of fighters from neighbouring countries, the secular Sunni and Salafist insurgents forged a durable opposition to Coalition governance which spread across Iraq in the wake of American sweeps of Fallujah in April and November 2004[55]. In addition, insurgents took full advantage of the global media during the first half of the Iraq insurgency to frame the conflict as one of Sunnis resisting the depravities and atrocities of the foreign occupiers. This monopolisation of the master narrative encouraged foreign recruits to join the insurgency for any number of personal motivations[56], creating a force multiplier for the insurgents which Coalition forces could not match in the early stages of the insurgency.

Amongst the counterinsurgents, the insurgents’ success in operating under the innovative strategic principles of new war from 2004-2006 points to an exceptionally slow lag time amongst Coalition forces in learning about and understanding the true nature of their opponents. The swift takeover of Iraq in 2003 corroborated the conventional understandings of warfare pervasive amongst US military strategists, who envisioned contemporary combat as a high-tech contest amongst states, a far cry from the Sunni insurgency’s true character as a sub-national uprising employing widely available global technology to sustain itself[57].

Beyond institutional resistance to new strategic doctrines, this fundamental misunderstanding of the insurgency permeated into how Coalition forces (particularly the US) interpreted and framed the connections between local and global dynamics of the insurgency, conflating new war’s globalised components with the Global War on Terror, where the enemy is similarly trans-national in appearance but highly divergent in their respective goals. For much of 2004, US forces considered insurgents fringe terrorist elements from outside the country and the last shreds of regime loyalists, ignoring the extent of localised opposition to the Coalition utilising new war as a blueprint for struggle instead of the end itself[58]. Accordingly, the disparity between Sunni insurgents’ and the Coalition’s understandings of the transformative potential of globalisation in conducting an insurgency led to major early successes for Sunni insurgents controlling much of the Sunni Triangle (and the Shi’as amongst their own population centres), with grievous costs inflicted on the Coalition as they sought to assert the legitimacy of the transitional Iraqi government.

The largely static annual rate of Coalition fatalities at 4 per 1,000 troops deployed in theatre from 2004-2006[59] (with a high absolute number of casualties) confirms the inability of Coalition troops to generate any significant progress in protecting themselves, a telling indicator of the Coalition’s failure to safeguard Iraqi communities due to the sheer number of “soft targets” amongst the local population. Indeed, this period featured a wave of suicide bombings, civilian kidnappings, assassinations, and executions of Iraqi hostages[60], hardly reassuring Iraqi local leaders about the merits of supporting the Coalition COIN effort.

The Coalition’s inability to deliver security points to a broader failure to provide a viable alternative to the sectarian shadow governments resisting the Coalition presence, for as Kalyvas mentioned earlier the outcomes of civil struggles are a product of which side can offer a more compelling sense of security and normalcy. For example, in late 2004 US forces made a concerted effort to win the “hearts and minds” of Shi’a residents in Sadr City in Baghdad by providing civil services such as waste disposal. However, they made little headway against the Mahdi Army since the Mahdists protected the population with regular policing, with US troops incurring heavy losses in this futile struggle[61]. Thus, COIN casualty rates from 2004-2006 proved emblematic of larger problems in defeating the insurgency, with the insurgents successfully disrupting and undermining Coalition efforts to restore Iraqi governance through a better understanding of the strategic landscape in the age of the globalised insurgency.

New Terror in Iraq 2004-2006

While insurgents’ institutional learning of how to conduct a globalised insurgency trickled downwards into their operations from 2004-2006, the dissemination of tactical insights and innovations within and across networks opposed to the Coalition and its Iraqi allies (both within and outside Iraq[62]) enabled deadlier attacks on Coalition forces. These attacks subsequently garnered global publicity and spread recruitment propaganda in a grassroots nourishment of the insurgents’ new war effort. The evolution of the improvised explosive device (IED)’s potency and ubiquity epitomises the importance of new terror’s networked methods in Iraq. In 2004, IEDs accounted for 26% of the combat deaths suffered by US COIN forces. However, by the first 6 months of 2005 IEDs accounted for close to 55% of combat deaths, a testament to insurgent adaptability[63]. Moreover, insurgents realised from their respective experiences that mixing crude and sophisticated IEDs in their attacks provided the best way to confound Coalition tactical adjustments[64], empowering diffuse and decentralised networks to inflict damage on Coalition forces with the minimal means at their disposure.

The Coalition’s tactical uncertainty from 2004-2006 was compounded by the sheer multiplicity of networks opposing the occupation of Iraq. Although these challengers were frequently lumped into the category of insurgents, opponents also included separatists, terrorist extremists, militias, and criminals[65], with the overlap between categories as well as the frequent merging, dissolution, and rebranding of their respective networks obscuring their identity and how best to defeat them. Thus, despite the inchoate organisational structure of the forces arrayed against the Coalition they possessed a coherent sense of how to inflict casualties on Coalition forces, leaving the Coalition to chase after a savvy, chimeric foe.

The fluctuating nature of Coalition casualties on a month-by-month basis points to what Hoffman described as an asymmetry between presumed Coalition forces’ successes and improvements compared with growing insurgent lethality[66]. In the Darwinian world of insurgency, US forces quickly killed most of the “dumb” ones in the insurgency’s incipiency in mid-2003. While this bloody trial-and-error improved insurgents’ techniques and tactics, their proficiency also increased as a result of the role of former military personnel who increasingly opted for the path of violence out of nationalistic and religious reasons[67], a testament to new terror’s disparate networks providing any number of cassus belli to the disaffected.

Although monthly fluctuations in Coalition casualty rates from 2004-2006 illustrate target-hardening amongst the counterinsurgent forces, it also reiterates the fundamental vulnerability of soft targets such as the civilian population to the growing lethality of bombing campaigns waged by networks of Sunni insurgents, their terrorist allies, and Shi’a militias. According to an Associated Press report, the year 2006 featured 3,000 more terror attacks in Iraq than 2005, with 5,800 more civilian deaths[68]. These grim tolls point to an abject lack of Coalition success in stemming the tide of attacks made possible by the advent of new terror on both Coalition forces and the local population they were entrusted to protect, precluding Coalition progress according to any barometer of success.

The Coalition’s struggles to deal with the networked approach of new terror from 2004-6 goes beyond the counterinsurgent’s customary lag time and initial disadvantages vis-à-vis tactical innovation against an indigenous opponent with superior human intelligence. Instead, the Coalition’s difficulty coping with new terror points to a flawed approach to tactical innovation in confronting the insurgent networks, where the Coalition sought to kill the hydra of anti-Coalition resistance by lopping off one head at a time and dismantling every individual network. The cells which comprise an insurgent network are highly decentralised; they often don’t know their leaders or their sources of finance.

Taken in combination with their bypassing of Coalition intelligence collection through low-tech methods[69], Coalition forces spent much of 2004-2006 in a never-ending quest to piece together intelligence on enemies with few formal links between one another. The Coalition’s initial tactics for interdicting network connections as well as the broader new war/new terror feedback loop underscores the Coalition’s initial ignorance of the nexuses amongst insurgent networks. During this early period of insurgency, Coalition forces (particularly the US) emphasised heavy-handed sweeps of the population for suspected insurgents[70], an approach which ignored how control of local populations provides the true means to sever insurgent networks from one another. To paraphrase Kaldor, Coalition forces from 2004-2006 sought to use out-dated tactics to fight a foe employing qualitatively new forms of organisation, attack, and communication, with grievous human costs for the counterinsurgents.

The Surge in Troops and Decline in Casualties

The COIN developments within the town of Qabr Abed serves as a microcosm for the trajectory of COIN casualties before, during, and after the surge, albeit 2 years prior to the surge itself. Coalition forces switched their operating procedures away from “search and destroy” targeting of insurgent networks to co-opting the local population’s support (a shift seen en masse in 2007 with the creation of the Sunni Awakening militias), removing the insurgents’ nearby sources of aid. Prior to Coalition occupation of Qabr Abed in November 2004, the city was run by Sunni extremists who compelled the population’s complicity on fear of death[71]. However, the permanent presence of Coalition troops within the village slowly shifted control of the population (and by extension its support) away from the insurgents and towards Coalition forces. Although Coalition casualties were initially high as the insurgents sought to dislodge the counterinsurgents, by July 2005 the collaboration of the population on security matters had shifted dramatically due to residents’ newly acquired confidence in the superior security proffered by the Coalition, with not a single counterinsurgent dying in the previous 5 months[72]. By safeguarding the population’s security, Coalition troops removed insurgents’ leverage over the community and by extension created safer condition for themselves, yielding a template for future success in Iraq.

The surge in US forces during the first half of 2007 marked the culmination of a profound development in institutional learning amongst Coalition forces. Taken together with the publishing of FM 3-24, these tectonic shifts in US COIN strategic doctrine institutionalised the aggregations of tactical insights discerned at the junior officer level in hotspots such as Qabr Abed[73]. Its overriding premise was to mirror the networked warfare conducted by insurgents, with battalions blending specialised units of infantry, armour, engineers, and other branches to rapidly disseminate information and ideas and undertake a range of counter-network operations[74]. At the strategic level, while the Coalition only gradually came to grips with the new war/new terror evolution in insurgent doctrine, they eventually realized that population control—through a continued presence amongst the local population and better sealing of the borders—remained as relevant in winning an insurgency as it had prior to globalisation. In short, the surge of US troops in Iraq in 2007 and subsequent decline of casualties points to more than the mere efficacy of population control, illustrating the precariousness of Iraqi insurgent networks born in the globalised crucible of Coalition occupation of Iraq.

As the “COIN-dinistas” advocating population control came to realise, a permanent presence amongst the population would transpose Coalition networks and linkages with the local community over the externally networked ties critical to sustaining new war, with these new linkages acquiring strength and durability as Sunnis sought succour and protection from their Shi’a foes amidst a bloody sectarian conflict. Indeed, for many Sunni insurgents not motivated by religious concerns the creation of new linkages with Coalition forces by 2007 provided a far better alternative than maintaining the frayed alliance with unsavoury religious extremists, where networks had originally forged out of little more than shared enmity with Coalition forces. Moreover, a continued presence amongst the local populace strikes at the primary weakness of new terror’s amorphous networked structure by providing a consistent and normalised security presence, generating increased local support which soon acquires its own momentum as the population shifts to support the safer side. The accretion of momentum in favour of the Coalition increasingly turned insurgent strongholds into pacified areas of tentative government support, driving down Coalition casualties and marking the formal end to Coalition occupation in 2009 as a tentative success.

B: The Curious Case of COIN Casualty Patterns in Afghanistan

A counterintuitive pattern in ISAF casualties has emerged in Afghanistan. Despite the institutional overhaul of US military operating procedures (the primary actor in COIN efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan) and ever-increasing troop numbers available to combat the insurgency and control the population, casualty rates have risen precipitously in recent years, with a nearly nine-fold increase in absolute hostile-related ISAF fatalities from 2005-2010[75]. This rise in casualties has been accompanied by a breakdown in nationwide security and a collapse of the always-tenuous central control. Indeed, with Iraq long providing a lightning rod for global jihadist funding and recruits and Taliban power shattered in the wake of the NATO invasion in 2001, how has Iraq emerged from its struggle as a fragile triumph for installing a popularly accepted government somewhat able to provide security to its people while the prospects for COIN victory in Afghanistan according to the same criteria appear so dim?

Although a number of structural factors—Western resources devoted to each conflict, rural vs. urban insurgency, and the salience of sectarian cleavages in derailing a united front against Western occupation, to name a few—contributed to the disparities in casualty patterns, these factors are a direct function of the Taliban’s resurgence and subsequent achievements (and emergence of their allies the Pakistani Taliban and Haqqani Network[76]). Instead, the Taliban’s resurrection stems from two overlapping explanations for insurgent success alluded to in the Introduction: 1) the abject failure of the Karzai government to establish security and a stable, predictable pattern of governance for the people[77], the most critical determinant in the success or failure of a COIN operation and 2) the Taliban’s creation of deeper and more robust networks than those encountered in Iraq, with extant traditional networks of commerce, taxation, and kinship harnessed to the undertaking of globalised insurgency.

Governance Failure in Afghanistan

Afghan governance since the fall of the Taliban in 2001 has exemplified Schelling’s game-theoretical model about the pitfalls of undertaking a cooperative effort amongst disparate institutions with unique institutional interests. Contrary to the Iraqi government’s gradual accretion of legitimacy through its increased ability to provide security to the local population, the Afghan government initially witnessed large-scale popular participation which abated as the divergent objectives of promoting development and increasing security have worked at cross-purposes. As a result, the unwieldy collaboration of Karzai’s government, NATO/ISAF, and NGO’s failed to meet popular expectations on either front as even the residual levels of Afghan insurgency proved disruptive[78].

At the confluence of development and security, seemingly capricious and iniquitous governmental policies have undermined perceptions of the government as impartial arbiters of local life, a distrust which permeates into the security sphere. For example, unfair crop eradication policies have tended to benefit rich landowners and tribal federations close to the provincial and federal power structures, driving many poor and powerless farmers in the southern poppy belt to join the Taliban to protect their livelihoods and general well-being[79]. Moreover, these imbalances frequently appeared to have a disproportionate effect on Pashtuns[80], progressively alienating the insurgency’s core ethnic constituency[81] from government participation in marked contrast to the efforts by the Coalition and the Iraqi government to make the political process more inclusive. Thus, the accumulation of these inconsistent and destabilising governmental policies left the loyalties of Pashtun-dominated local populations undecided in the years preceding the Taliban et al’s full-fledged resurgence, a balance which ultimately tipped towards the insurgency due to their more consistent and reliable delivery of security.

Amongst the Pashtun populations of Afghanistan, the Taliban’s ability to administer an efficient and consistent, if harsh, brand of justice and security under Sharia law vastly exceeds the mercurial and often predatory behaviour of the local police in government-held areas. As a Helmand resident succinctly put it, “security is 100% under Taliban. There are no robbers in the whole district. Justice is very effective[82].” With many Pashtuns wishing to be left alone and yearning for the security necessary to live without fear[83], Taliban governance fulfilled this simple request. As a result, the disaffection of Pashtun communities provided the node of popular support necessary for the linkage between new war’s strategic and logistical inputs and new terror’s networked innovation and cooperation across insurgent groups in Afghanistan.

Unlike the hastily created networks and connections in Iraq arising from broad opposition to Coalition occupation and based in large part on ascriptive ethnic identities (and only to a lesser extent on tribal lines due to the weakening of tribal elders’ control over young men wishing to join criminal gangs or the insurgency[84]), the Taliban-led resurgence blossomed over years of particular and deep-seated grievances at a variety of local levels of identification. This opposition to the Karzai government and its NATO backers culminated with concerted popular resistance in a society with a long tradition of resisting external occupation[85] and whose very functioning is predicated on interpersonal ties, the ideal environment for the creation of a hardy new war/terror feedback loop.

Globalisation and Afghan Insurgency: The Paradoxical Forging of Resilient Networks

Globalisation has had perverse effects on the perpetration of new war by the Taliban and its assorted allies. At the upper echelons of financing, logistics, and manpower, the Taliban has greatly benefited in recent years from reactivating its transnational links, with globalisation providing an impetus for tailoring traditional networks to Pakistan and the Gulf States to suit the demands of insurgency. The most globalised and most impenetrable source of funding for the Taliban stems from the drug trade. According to Gretchen Peters, 98% of Afghanistan’s poppy crop in 2008 was cultivated in the insurgent-dominated south and southwest, part of a symbiotic relationship with international drug traffickers where the Taliban received weapons and funding for their operations in exchange for protection and military muscle[86].

In addition, the Taliban’s collected revenue from protecting drug shipments and traditional taxations of both poppy farmers and other citizens is well-ensconced within the transnational credit network of hawala, a traditional, interpersonal, and completely unregulated informal economy extending between Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the UAE[87]. This merging of pre-globalised financial networks with the globalised market in arms, outside donations, and other supplies[88] is ideally suited for undertaking new war, creating an ephemeral, international operational apparatus based on interpersonal relationships which even the most sophisticated COIN technologies struggle to disrupt.

Conversely, at the ground level of Taliban opposition the insurgency provides an outlet for religious conservatives to oppose the globalisation epitomised by NATO occupation and its attendant inculcation of Western values[89], catalysing the construction of uncompromising, religiously motivated resistance networks. Although the concerted efforts by Taliban propagandists to replicate the early public relations success of the Sunni insurgents in Iraq have not fared nearly as well at the global level[90], the composition and attitudes of the Taliban insurgency on the ground nonetheless points to the Taliban’s fruitful creation of multinational networks blending local grievances with regional religious concerns to jointly combat Western moral influence in Afghanistan.

Taliban messages target a number of different audiences through its own input as well as contact with the mainstream media. However, the crux of Taliban communications seeks to recruit the local populations most disaffected with governmental rule yet maintain an umbrella of Islamic opposition to the dangers of Western cosmopolitanism on traditional Afghan society, a highly compelling sales pitch[91]. In short, the sheer number of ordinary insurgents from both Afghan and international backgrounds who feel compelled to fight against Western moral corruption in defence of Islam—an issue with little room for compromise[92]–in reaction to the years of Western influence in Afghanistan once again blends tradition with the vicissitudes of globalisation, yielding a new war infrastructure far more durable than the temporary networks of common interest arrayed against Coalition forces in Iraq.

New Terror and the Afghan Insurgency

Unlike the new terror linkages in Iraq sprung by a globalised backlash against the invasion of Iraq (creating an unwieldy web of cooperation between disparate groups such as ex-Ba’athists, religious extremists both Sunni and Shi’a, and disgruntled former soldiers[93]), the networks which emerged with the rebirth of the Taliban insurgency piggyback globalised methods of connectivity and cooperation onto traditional interpersonal networks. As a result, the insurgency forged in Afghanistan proved equally as amorphous and yet far less riven by internal divisions than its Iraqi counterpart.

The composition of the insurgent networks in Loya Paktia province epitomises how long-standing local ties of clan and tribe have fused with international organisations to create systems of close cooperation in southern and eastern Afghanistan, the heartland of Afghanistan’s insurgency. There are two regional networks led by the Haqqani and the Mansur families, with the Haqqanis nurturing deep ties to communities in the Gulf, Pakistani tribal areas and the Pakistani government itself along the Afghan-Pakistani border[94]. Besides them, there are Taliban groups acting independently from these two networks, led directly by the Taliban Supreme Council or by individual influential commanders in Quetta and operating throughout Afghanistan. Furthermore, separate structures of Hizb-e Islami (a separate country-wide insurgent network with international connections) have an insular operational base in Loya Paktia as well[95].

Like Iraq at the height of its insurgency, fault lines persist along tribal cleavages[96]. However, contrary to the exacerbation of tribal tensions in the Iraq insurgency networks by secular/religious schisms and sectarian divides the Afghan networks largely dampen tribal rifts with a distinctive geographical distribution, with Hizb-e Islami networks being dominant in strongly tribal areas and Taliban networks stronger in less tribal parts of the region[97]. With a strong foundation of personal ties which span generations underpinning these networks[98], the disparate insurgency systems in Loya Paktia and elsewhere transcend the outmoded forms of resistance which characterised the Taliban’s initial resistance in 2001, harnessing globalisation to yield a new terror infrastructure far more resistant to ISAF pressure.

The flow of manpower and technology from insurgents in Iraq made possible by globalisation has made the Taliban and affiliates’ new terror networks stronger than their Iraqi counterparts due to the vastly accelerated learning curve of tactical innovation and adaptation. Once again, IEDs encapsulate the quick dissemination of novel tactics across networks. In 2005, al-Qaeda sent a team of instructors from Iraq to pass on the latest techniques in fighting Western forces, particularly the highly effective IED[99]. Although the Taliban resurgence was still in its infancy, bomb attacks have risen steadily since, as new innovations diffuse within and across networks. Most recently, Afghan insurgents planted an astounding 14,661 IEDs last year, a three-fold increase from 2008 and a leading source of the dramatic rise in ISAF fatalities in recent years[100].

The decentralised and multinational command structure only amplifies the strength of Afghan new terror networks compared to those of Iraq. While Iraq’s command and control systems for new terror networks were almost entirely located within major Iraqi urban centres, Afghan networks enjoy rear bases in Pakistan’s hinterlands which include training and logistics support systems, political and religious leadership headquarters, a recruitment centre for full-time fighters, and a point of contact for external sponsors and financial backers[101]. As Kilcullen later noted in Counterinsurgency, ISAF is locked in an adaptation battle against a rapidly evolving insurgency that has repeatedly absorbed and adapted to past efforts to defeat it, including at least two enduring major troop surges and three changes of strategy[102]. This stands in stark contrast to the short-term troop surges in Iraq to provide security during the 2006 elections[103] and the 2007 troop surge which accompanied the overhaul of US COIN strategy. By intertwining the evolved insurgency techniques afforded by globalisation with long-standing community ties, the Taliban-led insurgency has made the nexus of the new war/new terror feedback loop—the local population, particularly amongst Pashtuns—far more impervious to ISAF population control methods than the Iraqi node, problematizing ISAF efforts to interdict this self-perpetuating feedback loop.

Conclusion

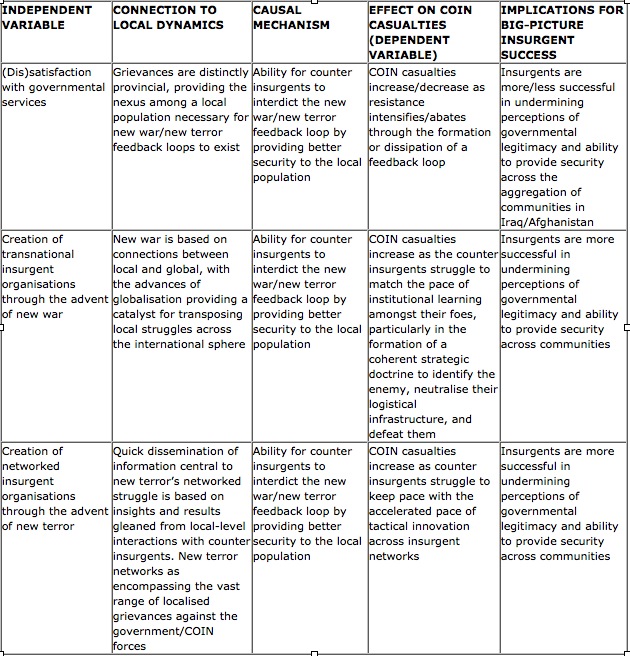

Although this work has traced the trajectories of the Iraq and Afghan insurgencies in broad strokes due to the exigencies of space, it nonetheless possesses one overarching trope inspired by the work of Kalyvas: the dynamics of localised struggle, connectivity, and contestation are the most critical component of these insurgencies, infusing meaning into understanding the big picture. To illustrate my point, a chart which process-traces my argument shows a clear progression from localised independent variables, a causal mechanism which mediates between these localised forces and the master cleavage within each insurgency, and the dependent variable of COIN casualties, a quantitative bellwether for the qualitative criteria of success for insurgents:

This utilisation of COIN casualty rates as an indicator of insurgent success provides comparative political scholars with a tool to surmount the oft-cited sui generis nature of insurgencies and draw connections within and across cases. With so many facets of insurgent success gauged by qualitative and highly transient criteria (popular perceptions, institutional learning, et cetera), casualty rate patterns provide a quantitative, substantive criterion for scholars to track as a starting point for subsequent research into globalised insurgencies (even determining the origins of globalised insurgency itself). For example, my framework for analysing the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan through the lens of casualty trajectories could easily apply to COIN undertakings such as Russian operations in Chechnya during the late 1990s and arguably to Turkish efforts against the Kurds, although some further disaggregation (e.g. Western vs. non-Western counterinsurgents) may be necessary to suit the particular research interests of the scholar.

Finally, COIN casualty patterns such as those in Iraq and Afghanistan provide Western policymakers and their voting publics with a tangible means to make informed decisions about policy choices in the undertaking of counterinsurgency operations. Although Western publics are not casualty-phobic and presently pay little attention to body counts in absolute terms as the ultimate barometer for success[104], they are wary of supporting wars with low prospects for ultimate triumph, and casualty rates and patterns can help them formulate more nuanced policy opinions[105]. Casualty patterns enable a holistic overview of counterinsurgent success over the medium and long term, allowing Western societies to confront the implications of Iraq’s mitigated threat and the Taliban’s recent resurgence through the ballot box and the policy initiative and make the decision best suited for saving lives.

Works Cited

Associated Press. “Terror Attacks Worldwide Rose 25% in ‘06.” 30 April 2007.

Azarbaijani-Moghaddam, Sippi. “Northern Exposure for the Taliban.” Decoding the New Taliban: Insights from the Afghan Field. Columbia UP, 2009.

Bloom, Mia. Dying to Kill. 2005.

Bob, Clifford. The Marketing of Rebellion. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Cloud, David. “US to Send 2 Battalions to Iraq to Help to Protect Vote.” New York Times, 24 August 2005.

Coghlan, Tom. “The Taliban in Helmand.” Decoding the New Taliban: Insights from the Afghan Field. Columbia UP, 2009.

Cordesman, Anthony. “The Developing Iraqi Insurgency—Status at End 2004.” Center for Strategic and International Studies Working Draft, 2004.

Dass, Niranjan. Globalization of Terror: A Threat to Global Economy. MD Publications, 2008.

Dolnik, Adam. Understanding Terrorist Innovation—Technology, Tactics, and Global Trends. Contemporary Terrorism Studies: Routledge, 2009.

Dunn, Peter. The American Army: The Vietnam War, 1965-1973. Armed Forces and Modern Counterinsurgency. Ed. Pimlott, Ian F.W. Beckett and John. Sydney: Croom Helm, 1985.

Fall, Bernard. “The Theory and Practices of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency.” Naval War College Review, April 1965 issue.

Gelpi, Christopher, Peter Feaver, and Jason Reifler. Paying the Human Costs of War. Princeton University Press, 2009.

Gilbert, Paul. New Terror, New Wars. Georgetown University Press, 2003.

Guelke, Adrian. The New Age of Terrorism and the International Political System. I.B. Tauris and Company, 2008.

Hashim, Ahmed. Insurgency and Counterinsurgency in Iraq. Cornell University Press, 2005.

Hammes, Thomas. “Countering Evolved Insurgent Networks.” Military Review 86.5 (2006).

Harmon, Christopher C. “Illustrations of “Learning” in Counterinsurgency.” Comparative Strategy 11.1 (2007): 29-48

Hoffman, Bruce. Insurgency and Counterinsurgency in Iraq. RAND Corporation, 2004.

Howard, Michael. “Foreign Fighters Leaving Iraq to Export Terrorism, Warns Minister.” The Guardian, 3 October 2005.

Jones, David Martin. Globalization and the New Terror. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2004.

Kaldor, Mary. “New and Old Wars.” Stanford University Press: 2nd Edition, 2006.

Kalyvas, Stathis. “New and Old Wars: A Valid Distinction?” World Politics 54.1 (2001) 99-118.

Kalyvas, Stathis. The Logic of Violence in Civil War. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Kilcullen, David. Counterinsurgency. London: Hurst and Company, 2010.

Kilcullen, David. “Taliban and Counterinsurgency in Kunar.” Decoding the New Taliban: Insights from the Afghan Field. Columbia UP, 2009.

Millen, Raymond A. The Political Context Behind Successful Revolutionary Movements. Nova Science Publishers Inc, 2010.

Nathan, Joanna. “Reading the Taliban.” Decoding the New Taliban: Insights from the Afghan Field. Columbia UP, 2009.

Ollivant, Douglas, and Eric Chewning. “Producing Victory—Rethinking Conventional Forces in COIN Operations.” Military Review (2006) 50-59.

Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom Casualties: http://icasualties.org/

Oppel, Richard. “By Courting Sunnis, GI’s See Security Rise in a Sinister Town.” New York Times, 17 July 2005.

Oppenheimer, Martin. The Urban Guerrilla. Chicago: Quadrangle, 1969.

Peters, Gretchen. “The Taliban and the Opium Trade.” Decoding the New Taliban: Insights from the Afghan Field. Columbia UP, 2009.

Petraeus, David. The Surge of Ideas. Speech at AEI Annual Dinner, 6 May 2010. http://www.aei.org/speech/100142.

Pirnie, Bruce and Edward O’Connell. Counterinsurgency in Iraq 2003-2006. RAND Corporation, 2008.

Ruttig, Thomas. “Loya Paktia’s Insurgency.” Decoding the New Taliban: Insights from the Afghan Field. Columbia UP, 2009.

Schelling, Thomas. The Strategy of Conflict. Second ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1960.

Smith, Graeme. “What Kandahar’s Taliban Say.” Decoding the New Taliban: Insights from the Afghan Field. Columbia UP, 2009.

Talbot, Steven and Paddy O’Toole. “Fighting for Knowledge: Developing Learning Systems in the Australian Army.” Armed Forces and Society 37.1 (2011): 42-67.

Tilly, Charles. Regimes and Repertoires. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

Trives, Sebastien. “Roots of the Insurgency in the Southeast.” Decoding the New Taliban: Insights from the Afghan Field. Columbia UP, 2009.

Whitlock, Craig. “Number of U.S. casualties from roadside bombs in Afghanistan skyrocketed from 2009 to 2010.” Washington Post, 25 January 2011.

[1] “Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom Casualties.” http://icasualties.org. Accessed 1 August.

[2] Tilly, Charles. Regimes and Repertoires, 2006. Page 35.

[3] Kilcullen, David. Counterinsurgency, 2010. Page 3.

[4] Ibid, Page 54.

[5] Kalyvas, Stathis. The Logic of Violence in Civil War, 2006. Pages 365-371.

[6] Schelling, Thomas. The Strategy of Conflict, 1960. Page 86.

[7] Bloom, Mia. Dying to Kill, 2005. Page 80.

[8] Ibid, Page 82.

[9] Bob, Clifford. The Marketing of Rebellion, 2005. Pages 14-15.

[10] Jones, David Martin. Globalization and the New Terror, 2004. Page 79.

[11] Dolnik, Adam. Understanding Terrorist Innovation—Technology, Tactics, and Global Trends, 2009. Page 5.

[12] Kilcullen, Page 2.

[13] Ibid, Page 3.

[14] Talbot, Steven and Paddy O’Toole. “Fighting for Knowledge: Developing Learning Systems in the Australian Army,” 2011. Pages 42-43.

[15] Kilcullen, Pages 2-3.

[16] Dolnik, Page 17.

[17] Dunn, Peter. The American Army: The Vietnam War, 1965-1973, 1985. Pages 85-95.

[18] Oppenheimer, Martin. The Urban Guerrilla, 1969. Page 22.

[19] Dolnik, Page 14.

[20] Bloom, Page 83.

[21] Harmon, Christopher C. “Illustrations of ‘Learning’ in Counterinsurgency,” 2007. Page 29.

[22] Hammes, Thomas. “Countering Evolved Insurgent Networks,” 2006.

[23] Kalyvas, Pages 119-124.

[24] Kilcullen, Page 159.

[25] Millen, Raymond A. The Political Context Behind Successful Revolutionary Movements, 2010. Pages 39-40.

[26] Kilcullen, Page 12. Also Hammes.

[27] Fall, Bernard. “The Theory and Practices of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency,” 1965. Also Kalyvas, Pages 218-219 and Hammes.

[28] Kaldor, Mary. New and Old Wars, 2006. Pages 2-8.

[29] Ibid, Pages 2-7.

[30] Gilbert, Paul. New Terror, New Wars, 2003. Pages 3-13.

[31] Kalyvas, Stathis. “New and Old Wars: A Valid Distinction?” 2001. Pages 99-100.

[32] Bob, Pages 4-5.

[33] Hammes.

[34] Kilcullen, Page192.

[35] Kaldor, Page 9.

[36] Kalyvas 2006, Chapter 11. Also Kalyvas 2001, Pages 100-109.

[37] Kaldor, Pages 10-11. Gilbert, Page 11.

[38] Kilcullen, Page 151.

[39] Bob, Pages 23 and 178.

[40] Bloom, Page 77.

[41] Gelpi, Christopher, Peter Feaver, and Jason Reifler. Paying the Human Costs of War, 2009. Page 2.

[42] Kilcullen, Page 3.

[43] Dass, Niranjan. Globalization of Terror: A Threat to Global Economy, 2008. Page 3.

[44] Jones, Page 20.

[45] Dass, Page 6. Also Jones, Page 164.

[46] Jones, Page 130.

[47] Guelke, Adrian. The New Age of Terrorism and the International Political System, 2008. Page 189.

[48] Jones, Pages 79-80.

[49] Dass, Page 10.

[50] Kilcullen, Page 4.

[51] “Operation Iraqi Freedom—Fatalities by Year and Month”. http://icasualties.org. Accessed 19 August.

[52] Pirnie, Bruce and Edward O’Connell. Counterinsurgency in Iraq 2003-2006, 2008. Also Hashim, Ahmed. Insurgency and Counterinsurgency in Iraq, 2005. Page 35.

[53] http://icasualties.org, accessed 19 August.

[54] Petraeus, David. The Surge of Ideas, 2010. http://www.aei.org/speech/100142.

[55] Hashim, Ahmed. Insurgency and Counterinsurgency in Iraq, 2005. Pages 37-46.

[56] Pirnie and O’Connell, Page 30.

[57] Kaldor, Pages 150-154.

[58] Cordesman, Anthony. “The Developing Iraqi Insurgency—Status at End 2004,” 2004. Page 2.

[59] http://icasualties.org for the casualty figures, accessed 20 August. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/ops/iraq_orbat_es.htm for Coalition troop sizes, accessed 20 August.

[60] Hashim, Page 35.

[61] Ibid, Pages 263-264.

[62] Cordesman, Page 14.

[63] Hashim, Page 191.

[64] Cordesman, Page 7.

[65] Pirnie and O’Connell, Page XIV.

[66] Hoffman, Page 15.

[67] Hashim, Page 33.

[68] Associated Press. “Terror Attacks Worldwide Rose 25% in ‘06”. 30 April 2007. Retrieved 21 August.

[69] Kaldor, Page 163.

[70] Hoffman, Bruce. Insurgency and Counterinsurgency in Iraq, 2004. Page 6.

[71] Oppel, Richard. “By Courting Sunnis, GI’s See Security Rise in a Sinister Town”. 17 July 2005. Retrieved 1 August. Page 1.

[72] Ibid, Page 2.

[73] Petraeus Speech.

[74] Ollivant, Douglas, and Eric Chewning. “Producing Victory—Rethinking Conventional Forces in COIN Operations,” 2006.

[75] http://icasualties.org for the casualty figures, accessed 25 August.

[76] Ruttig, Thomas. “Loya Paktia’s Insurgency”. Page 76.

[77] Trives, Sebastien. “Roots of the Insurgency in the Southeast”. Page 94.

[78] Ibid, Page 94.

[79] Peters, Gretchen. “The Taliban and the Opium Trade”. Page 12.

[80] Coghlan, Tom. “The Taliban in Helmand”. Pages 132-133.

[81] Ruttig, Page 86. Also Trives, Page 89.

[82] Coghlan, Page 140.

[83] Ibid, Page 133.

[84] Hashim, Pages 106-107.

[85] Azarbaijani-Moghaddam, Sippi. “Northern Exposure for the Taliban”. Page 250.

[86] Peters, Page 16.

[87] Ibid, Page 18.

[88] Ibid, Page 18.

[89] Smith, Graeme. “What Kandahar’s Taliban Say”. Page 209.

[90] Nathan, Joanna. “Reading the Taliban”. Page 34.

[91] Ibid, Pages 24-25. Also Smith, Pages 208-209.

[92] Smith, Page 209.

[93] Pirnie and O’Connell, Pages XIV-XV.

[94] Ruttig, Pages 75-77.

[95] Ibid, Page 59.

[96] IbId, Page 72.

[97] Trives, Page 89.

[98] Azarbaijani-Moghaddam, Page 250. Also Ruttig, Page 74.

[99] Howard, Michael. “Foreign Fighters Leaving Iraq to Export Terrorism, Warns Minister”. 3 October 2005. Retrieved 1 August. Page 1.

[100] Whitlock, Craig. “Number of U.S. casualties from roadside bombs in Afghanistan skyrocketed from 2009 to 2010”. 25 January 2011. Retrieved 1 August. Pages 1-2.

[101] Kilcullen, David. “Taliban and Counterinsurgency in Kunar”. Page 239.

[102] Kilcullen, “Counterinsurgency,” Page 51.

[103] Cloud, David. “US to Send 2 Battalions to Iraq to Help to Protect Vote”. 24 August 2005. Retrieved 1 August. Page 1.

[104] Gelpi, Feaver, and Reifler. Page 200.

[105] Ibid, Page 236.

–

Written by: David Rublin

Written at: London School of Economics and Political Science

Date written: September 2011

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Compassionate Warfare, a Hard Promise to Keep: COIN in Iraq and Afghanistan

- Incumbents vs Insurgents: Counter Insurgency’s Normative Reliance on Brute Force

- Power-sharing in Iraq as a Model for Afghanistan?

- Understanding Power in Counterinsurgency: A Case Study of the Soviet-Afghanistan War

- A Lineage of White Insurgency: US Capitol Attack and the Lost Cause

- Beyond Good and Evil: The Sources of US Strategy in Post-Invasion Afghanistan