A widely held middle class critique of Mexico’s governing institutions is that politicians are accountable only to the private elites and do not respond to middle and lower class needs. Indeed, with a history of oligarchic-type rule and pervasive government corruption, private sector elites have consistently been major players in Mexican politics. Massive privatization enacted through neoliberal reforms have especially empowered the wealthy elites who possess the resources to invest and expand in certain markets, thereby offering them even more privilege in the governing system.

On the other hand, the income convergence and widespread economic growth promised to middle and lower class Mexicans has not been delivered. Moreover, the presidential transition from the Institutional Revolutionary Party (Partido Revolucionario Institucional, or PRI) to the National Action Party (Partido Acción Nacional, or PAN) in 2000, and the more general opening up of democracy at other levels of politics around this time period, have failed to develop institutional practices that are distinct from the old priista regime. In this manner, as the rich corporations and political elite continue to prosper and the income inequality in the country remains the same, middle and lower class Mexicans have grown disenchanted with the way in which democracy is currently functioning in their country.

The present essay considers the impact of the relationship between the political and economic elite on democratic development in Mexico. Divided into three main sections, the first part of the essay establishes the role of big business in Mexican politics today, including a review of 1) the corporate capital gains tax, which has allowed large companies to evade paying taxes and has led to collusion between politicians and businessmen to maintain the system; and 2) the particular effects of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in terms of the opportunities it has provided for large corporations to become even more entrenched in politics and the subsequent consequences for the middle and lower classes. The second section applies institutional theory and the neoliberal model to analyze the aforementioned issues by reviewing the nature of institutions and practices between the government and private sector before and after NAFTA. Finally, the essay explores the development of civil society and democracy in light of the powerful and privileged private sector elite and NAFTA’s economic and social outcomes for the middle and lower classes.

Big Business and the Mexican Government: The Legacy of the 1973 Tax Modification

During the porfiriato in Mexico, it is estimated that around 300 families dominated the country. Former presidential candidate of the Party of the Democratic Revolution (el Partido de la Revolución Democrática), or PRD, Andrés Manual López Obrador (2010) suggests that not much has changed today. In fact, he proposes that around 30 individuals dictate the country for their personal and financial benefit, most being businessman and a few who are drug traffickers, including telecommunications tycoon Carlos Slim, Ricardo Salinas Pliego (brother of ex-president Carlos Salinas de Gotari), and infamous drug trafficker Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán (pp. 43-44).

Statistically speaking, 0.18% of Mexicans make up 42% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) according to information released in May 2011 by the Securities and Exchange Commission (la Comisión Nacional Bancaria y de Valores, or CNBV) and published in the widely respected newspaper La Jornada (González Amador, 2011). The CNBV recorded similar figures in 2000. Moreover, just three specific brokerage firms comprised 30% of the GDP, the first, Inversora Bursátil, owned by Slim (González Amador, 2011). Because so few control so much, large corporations are able to use this financial power in the political realm to influence policy decisions in the Mexican government.

Monterrosa’s (2009) analysis of the Mexican tax code for large corporations demonstrates just how connected these financial powerhouses are to the government, and the collusion that occurs to maintain the current benefits to big business. In 1973, former PRI president Luis Echeverría modified la Ley del Impuesto Sobre la Renta (ISR), or the law of capital gains tax, which taxes the income of individuals and corporations. With the objective of increasing investment and creating employment, Echeverría included special tax regulations for large companies in which they could simply defer tax payments until a later, unspecified date. An additional modification in 1982 allowed groups of companies to pay taxes as if they were one large corporation, promoting the creation of business conglomerates that could also defer tax payments. This law has also encouraged and permitted successful companies to incorporate failing businesses into their tax-paying consolidation; in this way, prosperous companies can deduct the losses of unprofitable businesses in order to document less profit during the fiscal year (Monterrosa, 2009).

Monterrosa (2009) estimates that due to these regulations and loopholes, approximately 400 consolidated companies paid an average of just 1.7% of their profits in corporate taxes in 2008, including Wal-Mart, Telmex, Bimbo, Elecktra, Televisa, Liverpool, and Palacio de Hierro. The 28 largest companies paid approximately 2.1% of their earnings (Monterrosa, 2009). Martinez-Vazquez (2001) reported a similar figure almost a decade earlier; he estimated that 350 consolidate groups, or 5,000 separate companies, were able to avoid paying substantial taxes in 2000. In his words, “tax compliance in the consolidation cases truly becomes voluntary and…tax policy makers unwittingly wrote a blank check to a powerful group of taxpayers” (Martinez-Vazquez, 2001, pp. 3-4). Small and medium businesses, on the other hand, pay 28% of their earnings to the government. Perhaps unsurprisingly, around 500,000 small and medium firms closed in 2009, with some likely making the transition into the informal economy (Monterrosa, 2009).

According to Martinez-Vazquez (2001), there are very few tax accountants who even have the capabilities to correctly follow the rules surrounding consolidation taxes or audit corporations’ tax returns, which allows the cycle to continue and frequent tax evasion to persist. Politicians have not attempted to do away with the privileges either; Monterrosa (2009) states that though the federal government has proposed that companies begin to pay their deferred taxes in increments, officials have yet to discuss abolishing the privilege once and for all. In the mean time, large corporations continue deferring tax payments and reporting reduced profit margins by incorporating less successful businesses into their tax-paying consolidations.

Martinez-Vazquez (2001) indicates that what is driving tax efforts to remain at constantly low levels for large corporations are the “negotiated tax burdens agreed upon by the government authorities and the representatives of the private sector” (p. 4). Politicians with business connections protect these corporations and defend their rights to continue deferring their tax payments. To generate more income for the federal government, the solution of the political parties, especially the PRI and PAN, is to raise the value added tax (VAT) on food and medicines (Dávila, 2011). With the VAT already at 16%, many lower class families struggle to purchase basic necessities. In sum, large, protected corporations continue to evade tax payments as they have done for more than three decades while the country remains in a fiscal crisis, and while the lower and middle classes are disproportionally burdened by the tax code.

Monterrosa (2009) puts a face to the collusion between the political and economic elite with the example of the Mexican Treasury of the Chamber of Deputies (la Comisión de Hacienda de la Cámara de Diputados) president Mario Alberto Becerra Pocoroba and the Interamerican Entertainment Corporation (la Corporación Interamericana de Entretenimiento, or CIE). Involved in sports betting, theater productions, musical shows, amusement parks, and the like, CIE is an international multi-million dollar company which owes a recorded $500 million pesos (approximately $49 million USD) in back taxes, and has probably evaded millions more, to the Mexican government. Becerra Pocoroba, known for his defense of companies who elude tax payments, conveniently sits on the board of directors for CIE. Though their debt is public knowledge, CIE’s taxes have yet to be collected and one can assume with confidence that Becerra Pocoroba is personally profiting from the pact. Examples such as this are frequent in Mexican politics and constitute the driving force behind the lack of significant tax reform for corporations.

Private Sector Interests and NAFTA

Though oligarchic-type rule and business interests certainly played a role in the Mexican government long before the neoliberal reforms of the late 1980s and early to mid 1990s, the NAFTA reforms embedded the private sector even deeper into Mexican politics and society. According to López Obrador (2010), former president Salinas de Gotari created a compact group of beneficiaries who would ultimately profit from NAFTA by reducing the role of the state and encouraging privatization. Indeed, Salinas began a massive privatization movement initiating over 900 sales including telecommunications, steel, railroads, airlines, shipbuilding, electricity and natural gas distribution, insurance, and the entire banking system (O’Neil, 2011). The only sectors untouched by the reforms were electricity and oil (Olvera, 2009).

The public goods transferred to private hands as a result of these reforms continued to be in control of this small, oligarchic group throughout the presidencies of Ernesto Zedillo Ponce de León and Vicente Fox Quesada, and still today under Felipe Calderón Hinujosa (López Obrador, 2010, p. 24). A clear example of a well-connected beneficiary of the reforms is Salina’s brother Ricardo Salinas Pliego, now a billionaire, who owns the conglomerate Grupo Salinas that includes Banco Azteca and TV Azteca, among other big-name telecommunications and financial companies (O’Neil, 2011).

It is evident, then, that a major result of NAFTA has been the inclusion of the private sector as an even more privileged member in Mexican politics. Thacker (1998) contends that structural adjustment policies produced a “new, financially-linked private sector elite” (p. 10) and “formalized a powerful coalition between a small number of outward-oriented big business elites and Mexican government technocrats” (Thacker, 1999, p. 72). Large Mexican firms clearly had the most to gain from a more open economy, as they were the actors with the capital and capacity to invest in private export industries.

Political actors, on the other hand, hoped to regain legitimacy, through economic growth fueled by the private sector to “retain a firm grip on the political infrastructure” (Poitras & Robinson, 1994, p. 7). In addition, the political elite were undoubtedly benefitting from “under the table” deals with the economic elite. The oligopolies and state monopolies that emerged in the 1990s remain connected to political power, and influence economic policy today (O’Neil, 2011).

NAFTA has produced less positive results for small and medium firms. In addition to paying higher taxes than corporations, NAFTA debilitated small and medium businesses by forcing them to depend on high-interest credit (Thacker, 1998). Additionally, special interest groups have impeded policy change regarding business and labor, fostering slow growth and great inequality in certain industries such as telecommunications, electricity, energy, and even bread and tortilla production (O’Neil, 2011). This has left consumers with few options and small and medium businesses with little hope of entering and competing in the market.

Though the NAFTA reforms certainly jumpstarted the dramatic increase in Mexico’s exports from $29.2 billion in 1990, to $189 billion in 2004 (Dawson, 2006), the policies have not generated more revenue for the state in the form of taxes, mainly because the private sector continues to exploit corporate laws. Olvera (2009) points out that when excluding tax revenue from the nationalized oil company Pemex, taxes accumulate to just 11.5% of GDP. This places Mexico as one of the lowest in the Western world in terms of tax systems (Olvera, 2009), only higher than Guatemala’s in the hemisphere (O’Neil, 2011). This figure has remained virtually the same pre- and post-NAFTA, hovering between 9% to 11.5% throughout the 1980s and 1990s as well (Martinez-Vazquez, 2001).

Consequences of NAFTA for the Middle and Lower Classes

To understand democratic development in Mexico, it is also important to highlight the economic and social consequences that structural adjustment policies have had on middle and lower class Mexicans. On one hand, neoliberals cite improvements for working-class Mexicans on several well-being measures since the ratification of NAFTA; for example, most Mexicans now enjoy a longer life expectancy, lower infant mortality, higher literacy rates, and higher completion rates in education (Dawson, 2006). On the other hand, Mexicans have simply not seen the income convergence promised through neoliberal reforms.

Prior to the major overhaul of trade policy and privatization, Salinas enacted a major social spending program to garner support for his administration (Poitras & Robinson, 1994). Through the Program of National Solidarity (el Programa Nacional de Solidaridad, otherwise known as PRONASOL) Salinas channeled around $65 million USD into infrastructure, schools, and basic services (Poitras & Robinson, 1994). The massive expenditure seemed to work for priistas as Mexicans appeared hopeful in response to the government’s spending on infrastructure and social services. However, spending was not sustained over the long term. According to O’Neil (2011), by the early 2000s Mexico was not only far behind other OECD countries, but was one of the last among Latin American countries in investment in infrastructure as a portion of GDP.

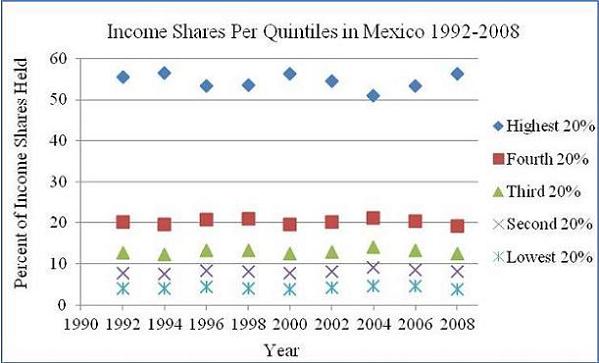

Middle and lower class Mexicans were disappointed once again when neoliberal reforms did not deliver widespread, economic growth across socioeconomic classes. An analysis of income data from the World Bank’s 2010 World Development Indicators clearly demonstrates this. Using income shares per quintiles as the indicator of income inequality from 1992 to 2008, the scatter plot indicates that the percentages have remained at the same levels over the selected time period. In regards to the highest quintile, the top 20% consistently accrued between 50% and 60% of the country’s income.

Smith (1993) actually predicted this potential outcome of NAFTA. He recognized the potential for neoliberal policies to reinforce the structural power of political and economic elites, the original promoters of orthodox market-oriented strategies, and increase class and regional disparities. In cases like Mexico where money has not been invested in infrastructure, but rather in low-labor and high-capital intensive export industries, job opportunities for the middle and lower classes are minimal.

Source: World Bank, 2010

In sum, liberalized, open trade policies and large-scale privatization have benefitted private sector elites and government officials who have worked together to control the domestic monopolies and also the export-production industries that have grown since the 1994 ratification of NAFTA. The working classes have not enjoyed the same privileges or tax breaks and have been burdened by structural adjustment policies. In this way, NAFTA has perpetuated a bifurcated society separated into the “haves” (who have quite a lot) and the “have nots.”

Applying Theory: Governing Institutions before NAFTA and Beyond

Mexican governance has struggled to break from the deeply entrenched corporatism that characterized institutions and the relationship between the private and public sectors under the PRI regime. With a powerful executive branch and weak legislative and judicial branches (Olvera, 2010), the post-revolutionary regime developed into a textbook example of a corporatist state described by Wiarda (2009), as a political system in which there is “not only a hierarchical system of caste and class but also a vertical system of separate, segmented, corporatist estates and professional associations” (p. 5). Regarding the private sector oligarchy, the strong state system incorporated wealthy elites into the political system not only to appease them and maintain control, but also to reap possible economic benefits as well. In this manner, though perhaps some policymakers genuinely believed that passing the 1973 corporate tax modification would stimulate growth, politicians were surely profiting as well.

The PRI’s establishment of the no-reelection policy also held significant consequences for the nature of governing institutions, and the relationship between business and politics. Banning reelection at all levels, the old regime created an extremely high turnover of federal and state deputies, as well as a state of practically permanent elections that still plagues Mexican governance today (Olvera, 2009, 2010). Moreover, in order to maintain their populist image and appeal to the masses, priistas throughout local, federal, and state levels became dependent on the private sector to fund their perpetual campaigns, thereby strengthening the private sector’s role in politics (Olvera, 2009). Prohibiting reelections also fostered an environment in which candidates had little incentive to enact significant change or attempt to fulfill the platforms on which they campaigned, often directed toward the lower and middle classes (O’Neil, 2011). Oftentimes politicians were less concerned with serving their constituents as they were focused on their own personal gains through making partnerships with the powerful, wealthy elite.

The aforementioned institutional problems that the PRI created are still present in Mexican politics, as neither the ratification of NAFTA nor the change of presidential party leadership in 2000 resulted in a significant modification in the nature of the state’s relationship with the elite private sector. As Mexico’s corporatist institutions have historically depended on elites in the private sector to maintain their dictatorship-like control in the country (e.g., through funding for constant campaigns) and for personal gains (e.g., money under-the-table), neoliberal reforms only provided an opening for big businesses to become even more powerful, and to continue to dominate the economic and political realms. Prior to the mid-1990s, stability was maintained through the bargaining of three main groups: the economic elite, the presidency and its state allies, and corporatists and populist groups (Poitras & Robinson, 1994). After NAFTA, however, the first two became the most important players, while the latter played less of a role. Poitras and Robinson (1994) state that since neoliberal reforms, “power within the multi-class coalition has now shifted towards those elites, both public and private, who share a commitment to market economy” (p. 5).

Despite civil society demands and the supposed opening up of democracy with the change in presidential leadership in 2000, the same issues with the corporate tax code and favoritism towards private sector elites remain. Simply stated, the change in political party did not change the institutional structure. In Olvera’s (2010) words, “instead of the emergence of the new political practices that the PAN and the PRD had promised to promote, the PRI’s methods and culture were generalized” (Olvera, 2010, p. 88). Moreover, O’Neil (2011) confirms that the formal and informal rules in Mexican institutions still limit transparency and accountability.

Additionally, the PRI has retained a considerable amount of power even after the transition. Holding the majority of state and municipal governments, the old regime has been able to veto many proposed changes of the new administration (Olvera, 2010). Moreover, even as the PRI has lost power and the PAN and the PRD have gained more local, state, and federal positions, the two parties new to the major political scene are sometimes weakly supported at the local levels and resort to recruiting priistas, which further perpetuates the old regime’s corporatist practices (Olvera, 2010).

In sum, the corporatist nature of the PRI’s institutional practices included a privileged position for economic elite, which was only strengthened by NAFTA. With a strong legacy left for the other two main political parties at all levels of politics, the relationship between the government and private sector will be difficult to change.

Effects on Democratic Development and Civil Society

The prominent role of private business and monopolies in Mexican politics and the economic structural outcomes of NAFTA carry significant social consequences for the country. Though under the neoliberal model the middle class should actually be the driver of democracy, Howard-Hassmann (2005) provides insight into how neoliberal policies can add to the middle class’s disillusionment with democracy. First, according to the optimistic model of neoliberalism that Howard-Hassmann’s (2005) describes, market reform should promote investment in the country (hopefully in sectors like infrastructure), which will provide employment opportunities and increase the size of the middle class. In theory, as the middle class grows larger, citizens will demand rights, ranging from property ownership to human rights, and essentially drive democratic development.

The pessimistic model, however, seems to be more accurate in Mexico’s case. Instead of channeling money into sectors such as infrastructure to create more jobs, in this situation “hot money” is invested in highly profitable sectors such as energy and oil (Howard-Hassmann, 2005). However, these investments are not necessarily initiated with long-term development in mind, and money may leave as quickly as it arrived in times of economic crisis or instability. In these cases, the middle class does not grow or become empowered. People become more disenchanted with their so-called democratic government, which does not seem to represent them, but protects private sector corporations and their investments.

Therefore, instead of creating great employment opportunities and wealth that trickles down, market reform has only benefited certain sectors and the wealthy elite in Mexico. Coupled with the fact that corporations continue to evade tax payments and the weakened state cannot provide quality social services, it is easy to understand why many Mexicans may arrive at the conclusion that the state only caters to important domestic and international players and does not act with their interests in mind. Furthermore, as no significant changes have emerged in the past two PAN presidencies, middle and lower class Mexicans have become more and more unsatisfied with the results of the democratic system and some remain without hope for change with any of the three major political parties.

In spite of the obvious faults of the political parties in the country, some scholars also cite the lack of civil society as a principle reason that democratic development in Mexico has not evolved in a more satisfactory manner. Villa Aguilera (2010), for example, proposes that the problems with Mexican democracy are not just institutional, but also stem from the lack of new forms of organization and citizen participation. From this perspective, citizens need to organize in more effective ways and participate more in the electoral process to promote democratic development.

This explanation, however, fails to recognize that the proper avenues to channel civil society’s unrest may not be effectively developed in Mexico. Civil society is certainly alive; citizens organize through a plethora of nongovernmental organizations to voice their concerns and discontent. In fact, in O’Neil’s (2011) opinion, the burgeoning civil society in Mexico may not be as strong as other parts of the region, but the “number, plurality, and vibrancy of civil society organizations, networks, and alliances is unprecedented” (p. 3). Similarly, Olvera (2010) credits civil society for major accomplishments in the country’s democratic development such as the founding and active participation of the Federal Electoral Institute (el Instituto Federal Electoral, or IFE) and Federal Institute for Access to Information (el Instituto Federal de Acceso a la Información, or IFAI). Additionally, social movements have emerged in opposition to the corporatist political parties, most notably the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (el Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, or EZLN) though smaller movements have also formed.

The problem is not a lack of civil society, but rather in the manner in which politicians receive it. Unfortunately, many political authorities do not take actors in public spaces seriously (Olvera, 2009). If concerns are addressed, they are dealt with in a corporatist, decentralized manner, as politicians negotiate with each organization or individual union instead of addressing larger systemic issues. Clientelism, paternalism, and favoritism are the “daily practices” between civil actors and government, and political parties have essentially substituted centralized corporatism with a decentralized form (Olvera, 2009).

In terms of specific political parties, the right-winged PAN and center-right PRI (the only parties that have controlled the country at the national level) have traditionally separated politics and civil society (Olvera, 2010). Surprisingly, the leftist PRD has also had limited success in fostering a productive relationship between civil society and government (Olvera, 2010). Again, considering the embedded practices of the PRI, even if an administration attempted to open up new public spaces on a larger scale, Olvera (2010) argues that the effort would be challenged by “the government’s programmatic and political limitations and civil society’s lack of concrete proposals and political strength” (p. 98). Because of this, Olvera (2010) contends that the only way to create a new relationship between civil society and the state is through a simultaneous reconstruction of prominent civil society actors and a true leftist party that share a common political goal.

Despite these obstacles, people continue to believe in democratic institutions. For example, the EZLN-led movement, “The Other Campaign,” called for an abstention in 2006 to protest the current political party options for the Mexican people, but was not a rejection of democracy itself (Olvera, 2010). Similarly, a common practice of the middle class is to go to the polls to cancel their votes. In this manner, though a significant proportion of middle and lower class Mexicans are seemingly disappointed with the options presented to them, these types of practices demonstrate support and hope for a democracy that has not yet been achieved in the country.

Conclusion

The corporatist tradition that lives on in governing institutions today is observable through the elite private sector’s substantial role in Mexican politics. Empowered by NAFTA and boasting the financial power to sway policies in their favor, the oligarchic business class appears to be the most important constituency for politicians. A lack of change to the long-established corporate capital gains tax that easily permits corporate tax evasion demonstrates the institutional challenges in modifying policy, and the potential corruption that occurs to keep such lax regulations in place.

On the other end of the spectrum are the middle and lower classes. Not having experienced widespread the economic growth and income convergence that was expected to occur following neoliberal reforms, people of this socioeconomic status have good reason to be disappointed in government policies. As the institutions and practices of the old regime have mostly continued despite the so-called democratic transition in 2000, the lower and middle classes have a right to be disillusioned with democracy. Unfortunately, channeling discontent through civil society actors and organizations has resulted in limited changes in the democratic development of the nation as well.

In O’Neil’s (2011) words, “it is unrealistic to expect a country to turn instantly from a closed corporatist economic system to an open competitive market, or from an authoritarian one-party state to a truly open, competitive, and inclusive democracy.” While this is certainly true, it seems that time and patience has run out for many Mexicans. With the 2012 presidential elections quickly approaching, Mexicans will undoubtedly search for a candidate offering a clear alternative from the past, but may be disappointed yet again when long-standing institutional practices constrain a true break from the corporatist model that has characterized the post-revolutionary state for decades.

References

Dávila, I. (2011, February 6). Innecesarios, más impuestos para obtener mayores recursos, afirma López Obrador. La Jornada. Retrieved from http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2011/02/06/index.php?section=politica&article=013n1pol

Dawson, A.S. (2006). First world dreams: Mexico since 1989. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

González Amador, R. (2011, May 11.). 0.18% de mexicanos concentran 42% del PIB. La Jornada. Retrieved from http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2011/05/11/index.php?section=economia&article=024n1eco

Howard-Hassmann, R.E. (2005). The second-great transformation: Human rights leapfrogging in the era of globalization. Human Rights Quarterly, 27(1), 1-40.

López Obrador, A.M. (2010). La mafia que se adueñó de México… y el 2012. Mexico City: Grijalbo Mondadori.

Martinez-Vazquez, J. (2001). Mexico: An evaluation of the main features of the tax system (Andrew Young School of Policy Studies Working Paper 01-12). Retrieved from http://aysps.gsu.edu/isp/2001_wp.html.

Monterrosa, F. (2009). El verdadero hoyo fiscal: 400 grandes empresas (casi) no pagan impuestos. Revista Emeequis, 195, 22-30.

Olvera, A.J. (2010). The elusive democracy: Political parties, democratic institutions, and civil society in Mexico. Latin American Research Review, Special Issue, 79-103.

Olvera, A.J. (2009). Sociedad civil, sociedad política y democracia en el México contemporáneo. Revista de Estudios e Pesquisas Sobre las Américas, 1, 1-15.

O’Neil, S.K. (2011). Mexico: Development and democracy at a crossroads. Council on Foreign Relations Expert Brief. Retrived from http://www.cfr.org/mexico/mexico-development-democracy-crossroads/p24089.

Poitras, G. & Robinson, R. (1994). The politics of NAFTA. Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs, 36(1), 1-35.

Smith, W.C. (1993). Neoliberal restructuring and scenarios of democratic consolidation in Latin America. Studies in Comparative International Development, 28(2), 3-21.

Thacker, S.C. (1998). Big business, the state, and free trade in Mexico: Interests, structure, and political access. Paper presented at the 1998 meeting of the Latin American Studies Association, Chicago, Illinois, September 24-26.

Thacker, S.C. (1999). NAFTA coalitions and the political viability of neoliberalism in Mexico. Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs, 42(1), 57-89.

Villa Aguilera, M. (2010). México, democratización de espuma: Sin participación ni representación. Estudios Políticos, 20(9), 11-28.

Wiarda, H.J. (2009). The political sociology of a concept: Corporatism and the “distinct tradition.” The Americas, 66(1), 81-106.

The World Bank. (2010). World development indicators [Data file]. Retrieved from from http://data.worldbank.org/.

—

Written by: Shaye Worthman

Written at: Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver

Written for: Dr. Lynn Holland

Date written: May 2011

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Development and Authoritarianism: China’s Political Culture and Economic Reforms

- Wind Energy in Mexico: Who Benefits?

- Piracy in the Southern Gulf of Mexico: Upcoming Piracy Cluster or Outlier?

- Populism and Extractivism in Mexico and Brazil: Progress or Power Consolidation?

- The Role of Global Governance in Curtailing Mexican Cartel Violence

- Racism and the Politics of Fear at the US-Mexico Border