To find out more about E-IR essay awards, click here.

Introducing the City to the International Political Economy (IPE)

The London Borough of Hackney was labelled the UK’s most deprived area by a British government survey in 2004 illustrating all 19 wards were in the top 10% of the most deprived nationally (HBC, 2006). The Hackney Financial Evidence Base (2006) stated that “between 56,374 and 62,400 adults…” were in relative poverty or living below 50% of the median income (less than £19,500) (DWP, 2011). An area of dilapidation and depredation notorious for its night-time culture, drugs, and extreme deprivation is juxtaposition to the financial landscape of London. Located six miles away is the Docklands, the main central network contributing to the prosperity of London. The Docklands is an area of great economic success dominating the world economy of finance and banking. The Docklands generates over £565 billion per annum and provides 1.5 million jobs (BIS, 2010). Thus, it is this juxtaposition the paper critically engages with to explore why a technological developed, prosperous and well connected city contains areas of deprivation disconnected from the circuit of wealth.

So why does this concern IPE? IPE is an enquiry into the relationships between the economy and politics exploring how one another influence each other with a particular focus on power (Ravenhill, 2008). These power relationships and political activities occur and impact space and place. For example; the failure of local government to channel funds into sustainable business projects in Hackney projects a particular geography to IPE. IPE would engage with conceptions of unevenness to globalization and decipher this process through units of analysis concerned with not only the politics of states, but the authority of cities and networks which inevitably impact the individual citizen (Sassen, 2006).

Actor-Network Theory (ANT) in IPE

Scholars (see Harvey, 2009 Sassen, 2006 and Massey, 2007) argue the process of economic globalization is to blame for the inequalities existing between cities, but most crucially within cities. Sassen (2006) conceptualises the world economy as a system of intense connections and networks providing a theoretical framework to answer the question:

Explain and explore how political actors within cities harness economic globalization to their advantage?

Sassen’s (2006) Actor-Network Theory (ANT) perspective of IPE in relation to the city aids our understanding towards analysing processes of connections and flows in complex systems. Economic globalization involves a seamless flow of connections of goods, capital, finance and labour constituting to form networks stretched across the globe and operating on local, national, international and global scales (Steger, 2009). Nevertheless, this paper undertakes a ‘glocal’ framework focussing both on those political actors at city-level but also global level to understand how they interact with economic globalization. Political ANT will frame this paper to understand the city as comprising of a series of strategic actors competing against each other to accumulate the benefits of economic globalization. Therefore, the paper can be situated in the broader discipline of neo-realism (see Waltz, 1990).

Scholars including Beaverstock are too focused on dedicating ANT theory onto the world cities and exploring their relationships with the global political economy (see Beaverstock et al, 2002). However, I transpose the ANT framework onto those places existing outside the city to understand their economic political relationships within the city. I shift away from traditional ANT theory to suggest all actors (nodes) are unequal and vast inequalities exist between networks in response to criticisms from John Law. Beaverstock’s ANT analysis is apparent in the following text, but it is used to develop the arguments of Sassen (2006) to explore the inequalities within world cities.

I will argue in the past that Hackney Borough Council (HBC) has failed to become a strategic actor in gaining entrance to the city network against the financial landscape of the London Docklands. Furthermore, I will discuss the local implications of economic globalization on Hackney through the case study of the 2008 Credit Crisis. In the second part of this paper I will explore the future plans for Hackney’s regeneration in the wake of the 2012 Olympic Games through critical analysis with the Hackney: A Host for 2012 report and two semi-structured interviews with two senior officials of HBC to argue how different actors can contribute to the regeneration of the city. Finally I illustrate regeneration as an effective tool in strategically engaging with economic globalization to reduce inequalities within cities.

In conclusion this paper will have presented economic globalization as an uneven process within the city benefitting only those strategic actors engaging with this development. Secondly, regeneration programmes in deprived areas of the city will be essential to gain entrance into the elite networks of the City. Finally, I will illustrate ANT as an effective critical lens that leads political scientists to understanding the complex interactions between IPE and the city, arguing politics can fundamentally drive economics.

Existing Outside the Network

The London Docklands

The London Docklands has been trading since the Roman era, booming in particular during the industrial revolution and Pax Britannica years (Ravenhill, 2008). However, during the Second World War (WWII) it was bombed heavily during the London Blitz causing destruction of all ports (Ray, 1996). At the time Britain was reliant on loans from the US (Marshall Plan) to restructure its economy. However, due to concerns over “dollar shortages” free trade seized up, inevitably leading to its demise (Gilpin, 2001:217). Post-war Docklands experienced manufacturing declines of 8% per annum between 1975 and 1978 as neoliberalism infiltrated the economies of the Far East, notably, the Asian Tigers (GLC, 1984; Ravenhill, 2008). Due to the monopolised nature of companies operating in the Docklands over 18,500 workers in just over 10 years lost their jobs (GLC, 1983).

Revisiting the ANT framework the Docklands demise was a result on both strategic nodes operating outside the city networks but most importantly, the failure of political actors to respond to economic forces of the manufacturing decline within city networks. The Docklands became disconnected from the rest of the city and the world economy for 13 years. Exogenous economic contributors included America’s role as ‘philanthropist’ sending aid over to Western Europe to prevent Soviet control during the Cold War period, which led to the dollar shortage and a dependency economic culture (Gilpin, 2001). Secondly, the move in the competitive advantage of manufacturing geographically shifted from London to Hong Kong and the other Asian Tigers due the failing and ineffective infrastructure left in post-war Britain. The failure of the Greater London Council (GLC) to redevelop the manufacturing industry in the Docklands and the seizure of national government to lend effectively to local councils or negotiate with foreign officials (Ravenhill, 2008). Thus, the malfunction of inside networks and outside networks led to the destruction of manufacturing in the Docklands as trading systems interconnected such networks together.

Excluding Hackney from the City

Hackney has never recovered from the bombing of the Second World War. Increasing competition from overseas i.e. Asian Tigers which meant between 1971 to 1980 Hackney experienced a 38% decline in its manufacturing industries (Ray, 1996). However, the key focus is the failure of governments and councils to undertake any form of regeneration in the area due to their financial concentration on the Docklands. Hackney currently has a £70 million debt and over 5% of its population in May 2006 was claiming job seekers allowance (JSA) compared to 3% in London and a national average of 2.3% (HBC, 2011). At present, 19.4% of the working population claims work benefits, 7% above the London average with 20% of households having at least £250 arrears and an average debt of £1,700 resulting from outstanding council tax (ONS, 2011; HBC, 2006).

The current situation in Hackney clearly illustrates the extent of juxtaposition against the financial landscape across the City of London. Therefore, Hackney can be understood as financially marginalised due to its failure to embrace regeneration and connect nodes and circuits back into the city and global economy. As Sassen (2006) has argued places like Hackney are the result of the territorial dispersal of economic activities which inevitably leads to the centralization of growth. Events including, the 2008-09 Credit Crisis have challenged a number of projects from being undertaken by HBC to improve the situation. The case of the Credit Crisis has exacerbated and slowed Hackney’s economic progression towards connectivity with the City.

Credit Crisis

In 2008-09 the result of a collapse of subprime mortgages rippled throughout the global economy striking the heart of the City, consequently causing banks to seize lending and an implosion of consumer confidence in financial markets. Those peripheral or external nodes existing outside the networks i.e. Hackney were hit the worst for two reasons. Firstly, their dependency on single markets and failures to diversify due to lack of connections within the city and outside the city networks, thus, when one channel of income was closed off this crippled the node. Secondly, the financial alienation of Hackney meant it was unable to quickly recover using other sources of incomes for support. Lack of connections and failures of economic diversification by the council and the government resulted in sixty-six businesses closures between 2008-09 (Frankish and Roberts, 2009).

In 2010 the local council cut its budget by £44 million in conjunction with loses of £32.8 million due to residents failing to pay council tax. The population became transient as people seek alternative employment in surrounding boroughs (Nieburg, 2011). The most prevalent reason for Hackney’s deprivation is due its financial exclusion from the City. The significant oversee of “social and economic regeneration…” has resulted in Hackney becoming financially marginalised due to its lack of effective infrastructure including, transport, telecommunications and other financial businesses (HBC, 2006:04). Financial transnational corporations (TNCs) are attracted to regenerated areas as they provide confidence and hopes of prosperity to stakeholders (Daniels, 1993). Thus, due to Hackney’s failures to redevelop and rebrand it became alienated from financial networks within the City.

Conclusions

Existing outside the elite city network has proven to be detrimental to the economic stability of Hackney both in the private sector and public sector. Hackney’s failure to strategically harness economic globalisation during its stages of deindustrialisation meant it became disconnected from the rest of the City both economically and socio-politically. The financial crisis of 2008 has exacerbated such financial alienation from the core of the network and crippled Hackney into economic negativity.

Gaining Entrance to Networks

Thatcher’s Docklands

The Thatcher government (1980s) transformed the Docklands under one of the greatest regeneration schemes in Western Europe to integrate the Docklands back into the world economy. Spending c. £2,100 billion of government funds, the Docklands was about to become the most competitive and specialised area in the world for finance and banking (Brownhill, 1993). The evolution of the Canary Wharf development represented an era of financial neoliberalism, wealth and an embracement of the free-market. The attractiveness of such a development lay in its flexibility and accommodating statue which Thatcher and her government promoted through mass deregulation and privatisation (Imrie et al, 2010). Flexibility allowed the evolution of a multitude of new connections which transmitted over to the financialization of New York and Tokyo but also over to the industrialising Asian Tigers. Infrastructural development including the build of the Docklands Light Rail (DLR) and London City Airport (LCA) stimulated flows of people to Canary Wharf. Transport became important as it could facilitate the flows of people with specialist knowledge of banking and finance to locate at the Docklands in order to generate economic efficiencies and productivity. Subsequently, residential housing was constructed in order to temporarily or permanently house financial migrants. The partnerships between private and state promoted by Thatcher led to the Private Finance Initiatives (PFIs) which are still an effective tool in harnessing globalisation. The regeneration process created over 1.5 million jobs, produced over £565 billion per annum and facilitated 36.7% of world foreign trade (BIS, 2010).

2012 Olympic Package

HBC’s main aim is to “globalise Hackney for the 21st Century…” make it an area of stronger connections through the promotion of financial investment and tourism (Senior Official, 2012). The ‘Multi-Area Agreement’ set in motion by the council and part of a strategic PFI solidified cooperation between the state and private business including Barclay’s Bank and Global Finance. The agreement attempts to reconnect Hackney with the City and the global economy (HBC, 2007). The agreement will not only place Hackney on the ‘Tube Map’ but create 50,000 jobs in local, national and global finance companies funded partly by the competitive networking and technology company, Cisco Systems (Senior Official, 2012). Nevertheless, the project is not only global but operating on a local scale as well to “involve all of the community in the ‘Games’.” (Senior Official, 2012). Subsequently schools will become the foundations in establishing a successful future for Hackney, connecting students with local businesses to give them the opportunity to be part of the games, offering work experiences and internships (HBC, 2012).

The ‘glocal’ framework adopted by the Council is one unrecognised by Sassen, offering a fresh perspective within ANT. Robertson (in Featherstone et al, 1995) redefines globalisation, suggesting equality is maximised within places and between places by focusing state and private resources on different scales to benefit a variety of people. Thus, one of the key predicted impacts reinforced by the Head of Regeneration Delivery at HBC is “involving everyone in the regeneration process to benefit the whole community.” To make Hackney a place of global interest (Senior Official, 2012).

The Future for Hackney

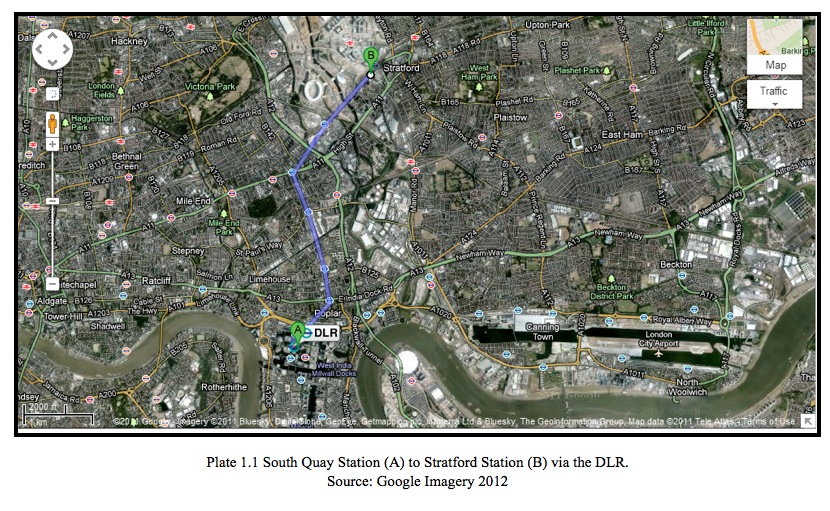

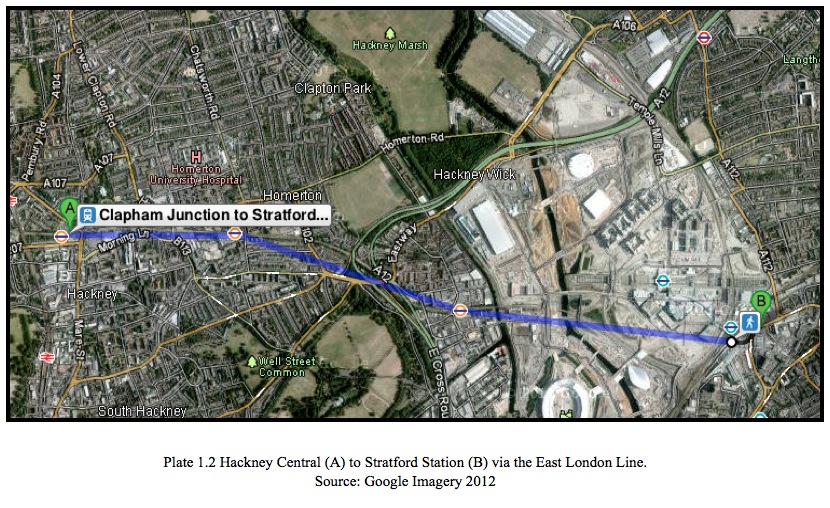

PFIs are an effective way of harnessing economic globalization, reinstating state control over economic forces. One of the major parts of the regeneration package is the construction of an extension on the East London Line and major investments on the Northern Line to link Hackney to the ‘Tube’ network. The establishment of the DLR caused regeneration waves across Stratford and Newham (Florio and Edwards, 2001). Stratford has seen the increase in new affordable housing, community sports and cultural facilities, and better transport as a result of its connections with the DLR (BIS, 2010). Transport systems allow social mobility across local, national, and global boundaries thus, crystallize the importance of PFIs. Plate 1.1 displays the connection between South Quay, Docklands and Stratford, East London illustrating the importance of transport in aiding Hackney to become part of the network city (Plate 1.2). Subsequently, the rail connections will fulfill the vision by Mayor Pipe of Hackney to become a global hub (HBC, 2012).

Job creation is another major consequence of the Council working with Olympic contractors, financial TNCs and Cisco Systems. It is estimated from the projections provided from the semi-structured interviews and the data of the report that almost 150,000 jobs will be created across Hackney and its surrounding areas (Senior Official, 2012; HBC, 2007). Nevertheless, one senior official of regeneration for Hackney believes job creation will divulge into a ‘domino effect’ nationally and globally via various strategic political actors and private organisations (Senior Official, 2012). Employment growth leads to gentrification through the implementation of PFIs enabling people to reconnect to elite networks of the City of London. The reconnection process occurs mostly between growing businesses become large enough to trade with organisations in the City of London. Therefore, out of job creation, business development and enlargement can be seen in the recent examples of Stratford but also of the older illustration of the Docklands (see, Daniels, 1993).

Evaluations

It is important to note the sources used to evaluate Hackney’s predicted successes were based on material provided by HBC and therefore, statistical and discourse analysis of primary sources may be subject to a particular perspective. Denscombe (2008) highlights the subjective nature of using qualitative data. Thus, this paper has attempted to also use statistics from both HBC and the government to strengthen confidence in the data collected. Finally, I recognise the constraints on using the ANT framework as a ‘modelled’ approach and failing to take into account the complexity of decisions humans have to make (see Bijker, 1992). However, as outlined this research has focused on political actors as units of analysis and predict how economic globalisation can be harnessed by politics.

Conclusions

The case studies illustrated throughout this report engage with the crux of the ANT framework of competition between nodes in the network and advocating only those actors strategically competing will receive the successes from other networks and the global economy (Sassen, 2006). Broadening the geographical scale, ANT theorists can transpose this argument onto the divide between the North and South of England. The scale can be widened further through Wallerstein’s (2004) World Systems theory projecting the unevenness of economic globalisation between the global North and South. For example, Britain and the West’s role of strategically undertaking colonialism to expand under the ‘law of capitalist imperialism’ to create new markets, which were divided up to compete with each other to benefit the West due to cheaper factors of production (Gilpin, 2001). Secondly, both the Docklands and Hackney provide a justification to argue regeneration programmes in deprived areas can reconnect nodes to important networks within and outside the city. Transport connections, ‘financialisation’, and social reforms are crucial to steering places out of stagnant economic waters, sailing towards a growth and prosperity. Regeneration is also a route towards economic sustainability within the city’s networks as schemes usually require the diversification of income streams/money flowing in. For example, Hackney not only is reliant on foreign direct investment from financial TNCs but has promoted itself as a global place for tourism and residency.

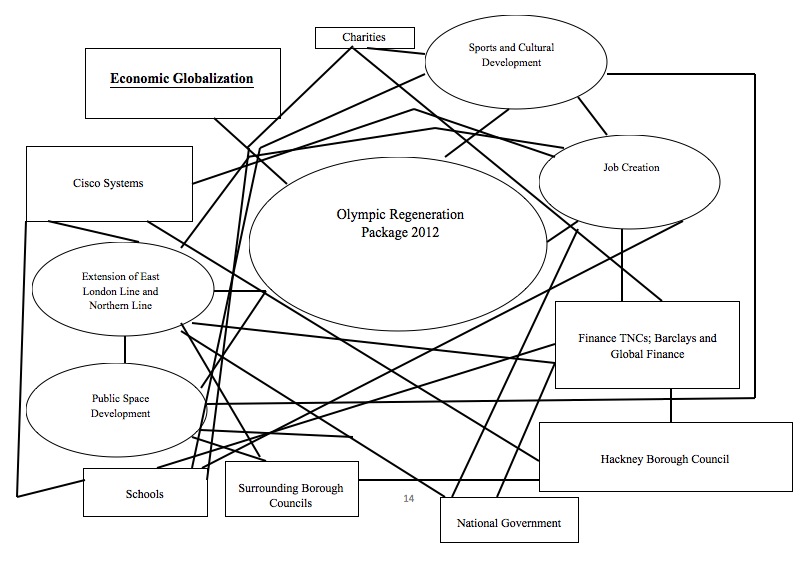

Finally, ANT theory has demonstrated to be an effective critical lens that deciphers some of the complexities within the IPE of the city. Appendices C (Page 13) attempts to visualise this report by illustrating some of the key nodes operating within this particular network to engage successfully with economic globalisation through policies of the 2012 Olympic regeneration package. ANT breaks-down the complex connections, processes and networks operating within the global economy and within cities. It has proven to simplify some of the key debates over economics and politics to illustrate political actors can use economic forces to their advantage.

Bibliography

Beaverstock, J. Doel, M. Hubbard, P. And Taylor, P. (2002) Attending to the World: Competition, Cooperation and Connectivity in the World City Network, Global Networks, 2(2), 111-132.

BIS (Department for Business, Innovation and Skills). (2010) Understanding Local Growth, http://www.bis.gov.uk/assets/biscore/economics-and-statistics/docs/u/10-1226-understanding-local-growth [Accessed, 06/02/2012].

Bijker, W. (1992) Shaping Technology/Building Society: Studies of Sociotechnical Change, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Massachusetts.

Brownhill, S. (1993) Developing London’s Docklands: Another Great Planning Disaster? Paul Chapman Publishing Ltd, London.

Daniels, P. (1993) Extending the Boundary of the City of London? The Development of Canary Wharf. Environment and Planning A 25(4). 539-552.

Denscombe, M. (2008) The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects. Open University Press, Berkshire.

DWP (Department for Work and Pensions). (2006) Households Below Average Income, http://research.dwp.gov.uk/asd/index.php?page=hbai_arc#hbai [Accessed, 06/02/2012].

Florio, S. And Edwards, M (2001) Urban Regeneration in Stratford. In Stubbs, M. Planning, Practice and Research. 16(2). 121-144.

Frankish, J. And Roberts, R. (2011) Measuring Business Activity in the UK. Warwick Business School, Warwick.

Gilpin, R. (2001) Global Political Economy: Understanding the International Economic Order, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

GLC (Greater London Council). (1983), The East London File, GLC, London.

(1984), Housing and Employment in London’s Docklands, GLC, London.

Google Imagery, (2012) Hackney Central Station to Stratford via East London Line, http://g.co/maps/jj87h, [Accessed, 08/03/2012].

Google Imagery, (2012) South Quay to Stratford via DLR, http://g.co/maps/k8jkn, [Accessed, 08/03/2012].

Harvey, D. (2009) Social Justice and the City, University of Georgia Press, Georgia, 50-94.

HBC (Hackney Borough Council). (2006) Hackney Financial Exclusion Evidence Base, Hackney Financial Inclusion Steering Group, London.

(2007) Hackney: A Host for 2012, Hackney Borough Council, London.

(2011) Employment and Unemployment Figures for Hackney, http://www.hackney.gov.uk/xp-factsandfigures-employment.htm [Accessed, 06/02/2012].

(2012) London Olympic and Paralympics Games, Hackney Borough Council Online, http://www.hackney.gov.uk/x-olympics.htm [Accessed, 06/03/2012].

Law, J. And Hassard, J. (1999) Actor Network Theory and After, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 01-15 and 74-90.

Massey, D. (2007) World City, Polity Press, Cambridge, 95-149.

Nieburg, O. (2011) Council Fails to Collect £30m in Tax Bills, Hackney Post, http://hackneypost.co.uk/2011/03/24/council-fails-to-collect-30m-in-tax-bills/#more-5203 [Accessed, 15/02/2012].

ONS (Office of National Statistics). (2011) Annual Population Survey, Quarterly Release, ONS, London.

Ravenhill, J. (2008) Global Political Economy, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 03-95.

Ray, J. (1996) The Night Blitz: 1940-1941, Cassell Military, London.

Robertson, R. (1995) Glocalization: Time-Space and Homogeneity-Heterogeneity, in Featherstone, M. Lash, S. And Robertson, R. Global Modernities, SAGE Publications, London.

Sassen, S. (2006) Cities in a World Economy, Sage Publications, Chicago.

Senior Officials (2012) Semi-Structured Interview with Head of Regeneration Delivery Conducted Monday 5th March & Tuesday 6th March 2012, Hackney Borough Council, London.

Swyngedouw, E. (2003) Globalization or ‘Glocalization’? Networks, Territories and Rescaling. Oxford University, Oxford.

Steger, M.B. (2009) Globalization: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Wallerstein, I. (2004) World Systems Analysis: An Introduction, Duke University Press, North Carolina.

Waltz, K. (1990) Realist Thought and Neorealist Theory, Journal of International Affairs, 44(1), 21-37.

The author would like to thank Ben O’Loughlin and John Abraham for acknowledging the potential of this student essay to be submitted as an online academic journal; Hackney Borough Council for providing a wealth of primary literature through the two senior officials referred to in this report; fellow classmates for their constructive criticisms and sustained encouragement over the course of developing this research; and finally, family and friends for their ongoing support and belief.

—

Written by: Connor Lattimer

Written at: Royal Holloway, University of London

Written for: Ben O’Loughlin

Date written: March 2012

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Harnessing Alterity to Address the Obstacles of the Democratic Peace Theory

- Iceland and the Vatican City: Small State Agency in International Politics

- Soviet Legacies and the Consolidation of Economic Rentierism in Kazakhstan

- Are You a Realist in Disguise? A Critical Analysis of Economic Nationalism

- Malaysian Language Policy: The Impact of Globalization and Ethnic Nationalism

- Ideology and Economic Policy in European Social Democracy c.1890-2010