1. Introduction

The debate on Civil-Military Cooperation in Post-Taliban Afghanistan dates from the introduction of Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs)[2] model in 2003, with the primary goal to assist the central government in providing security at the sub-national level, facilitating civil-military cooperation and implementing small scale reconstruction projects (Hugh, 2004). In practice, the simultaneous involvement of international civilian actors and military institutions along with increased integration of relief operations into political and military strategies have seriously elevated a series of problematic issues concerning the present Civil-Military Cooperation trend in Post-Taliban Afghanistan (Jenny, 2007).

The armed humanitarian division of international military have continued operating in unsecure Afghan local communities claiming to assist NGHAs mission by providing humanitarian and development assistances. However, NGHAs have consistently expressed their concerns by pointing out a number of negative implications, as a result of military involvement in relief operations (Sedra, 2005). The repeatedly expressed concerns by NGHAs are: undermining of humanitarian principles, overlapping and unsustainability of projects, increasing figures of targeted NGHAs by insurgents and ultimately, limiting the space for humanitarian actors in the local communities (Dziedzic & Seidl, 2003).

This paper focuses on the present approaches of Civil-Military Cooperation in Afghanistan and attempts to answer the following questions:

“How has the present Civil-Military Cooperation approach in Post-Taliban Afghanistan affected the Non-governmental humanitarian agencies in providing humanitarian relief? How can this trend be improved?”

This essay begins by evaluating the role of the military, represented by the PRTs, in delivering humanitarian and development aid in Post-Taliban Afghanistan and highlights a variety of destructive consequences for NGHAs, caused by military involvement in relief operations. In addition, the essay takes a step forward and employs Theory of Shared Responsibility (Blend,1999) and Theory of Regime (Krasner, 1983) to sketch out the possible courses of action for improving Civil-Military Cooperation in post-Taliban Afghanistan in future humanitarian and development joint-efforts.

2. Defining Terminologies and Introducing Actors

For reasons of conciseness of this article and particularity of the context of Post-Taliban Afghanistan, the paper intentionally divides the engaged actors in civil-military cooperation in two general groups: 1, Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs) and 2, Non-governmental Humanitarian Agencies (NGHAs). Each of the groups –in some cases indirectly – encompasses all the international military and non-military actors who are operating in Afghanistan. The term, Non-governmental Humanitarian Agencies (NGHA), which is deliberately used in this paper, encompasses national and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs), International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and humanitarian agencies within the UN system (Sedra, 2005). Likewise, Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs) includes the all the international military forces including NATO, ISAF and coalition Special Forces. Similarly, it includes all other armed institutions operating under structures of PRTs in Afghanistan.

Since the nature of PRTs and NGHAs are remarkably different with each other in terms of organisational structure, operational culture, and their goals and approaches in addressing reconstruction and development in Post-Taliban Afghanistan (Brzoska, 2008), it is essential to separately have a deeper look at both of the actors.

2.1. Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs)

Shortly after the fall of the Taliban regime in late 2001, the coalition forces created a Joint Civil-Military Operations Task Force (CJCMOF) to manage and coordinate the civil-military interactions in Afghanistan (Sedra, 2005). The second step was establishment of Coalition Humanitarian Cells (CHLCS) under the auspices of CJCMOF in several key provinces. The main objective of the CHLCs was to conduct ‘winning hearts and minds’ operations by implementing humanitarian and development programs in Afghanistan. In addition, the political agenda of these cells were obtaining positive publicity for the war efforts in the United States, on the one hand, and securing the support of local Afghan populations, on the other.

Finally, in mid 2002 the need to accelerate the reconstruction and development efforts in Post-Taliban Afghanistan has led the U.S Led Coalition Forces to seek ways of decentralising ISAF at the provincial level. As a result, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) developed the concept of civil-military field units throughout Afghanistan. The concept was supposed to be implemented under the name of Joint Regional Teams (JRTs); however, due to the suggestion of the Afghan President, Hamid Karzai, the teams started operating under the name of Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) in Gardiz province for the first time in 2003 (Dziedzic & Seidl, 2003). At the time of writing this paper, there are 26 PRTs operating across the country. Structurally, PRTs are composed of various military and civilian bodies including diplomats, specialists in economic development and governance and a few representatives of the Afghan government.

2.2. Non Government Humanitarian Agencies (NGHAs)

The involvement of NGHAs in Afghanistan in delivering humanitarian assistance goes far beyond the collapse of the Taliban regime. The first officially registered non-governmental humanitarian agency in Afghanistan was International Committee of Red Cross (ICRC), which started operating in 1979. According to the figures given by the United States International Grantmaking (USIG), a total number of 4,280 NGHAs are currently operating in Afghanistan. (USIG, 2012)

In general, any national or international non-governmental humanitarian organization operating in armed conflicts or post-conflict contexts are committed to comply with the core humanitarian principles namely: a, Principle of Humanity, meaning that all victims should be treated and respected equally at any circumstances by saving lives and alleviating suffering. b, Principle of Impartiality, meaning that humanitarian assistance should be based on need, and must not be based on race, religion, nationality or political view. c, Principle of Neutrality, meaning that no sides should be taken with any warring parties during or after the armed conflict (Anderson, 1999).

However, it is an internationally accepted principle that NGHAs neither follow any political agendas nor is it supposed to be utilized as a political instrument by any government for any purpose; some argue that that since the end of the cold war, humanitarian aid has increasingly been politicised. A counterargument is always opposed to this by claiming emerge of “new humanitarianism” which aims to assist peace building trends in fragile states by addressing poverty (Brzoska, 2008).

3. Civil Military Cooperation in Post-Taliban Afghanistan

After the fall of Taliban regime, development and humanitarian assistances have been recognized as one of the essential commitments of the international community towards reconstruction and development of Afghanistan. Another aspect of this strategic commitment was launching counterinsurgency and peacekeeping operations to ensure security (Runge, 2009). Therefore, one of the initiatives of the international coalition was introducing the PRT model with the objective of providing security and facilitating humanitarian and development interventions at the provincial level. After this model was successfully implemented in Garzdiz Province in 2003, the PRTs soon expanded and started operating in 26 provinces under the command of North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

Establishment of PRTs in Afghanistan rapidly led to the massive involvement of military, through the PRTs, in delivering humanitarian and development assistances. This humanitarian nature of PRTs raised intense debates concerning Civil-Military Cooperation trend among the humanitarian actors, especially due to the fact that the military humanitarian activities has blurred the line between humanitarian and military actors in the ground and seriously affected the neutral and impartial image of NGHAs among the local Afghan communities. It is worth to mention here that in recent years several civil-military cooperation guidelines have been developed by the UN agencies and other NGHAs to improve the trend but none of these guidelines proved to be effective in improving Civil-Military Cooperation in Post-Taliban Afghanistan. In contrast to what Thomas G. Weis, the author of Military-Civilian Interactions (1999) argues that the main role of military in the humanitarian space is to provide security and logistics. In Afghanistan, the PRTs have conversely accelerated their “winning hearts and minds” operations by launching a huge number of quick-impact programmes, aiming to gain community support. These operations, however, did not adhere to the humanitarian organizations standards, as constantly claimed by NGHAs ((Hugh, 2004).

Surprisingly, it is not only the NGHAs who criticise the PRTs involvement in development and humanitarian affairs, very precise criticisms were made by the Afghan president, Hamid Karzai who mentioned that:

“Afghanistan clearly explained its viewpoint on Provincial Reconstruction Teams and structures parallel to the Afghan government … bodies which are hindering the Afghan government’s development and hindering the governance of Afghanistan” (BBC, 2011).

However, NGHAs are concerned and the Afghan Government is frustrated concerning the deficient civil-military cooperation in Post-Taliban Afghanistan, the United States has officially endorsed – in addition to PRT’s three main areas of responsibilities: security, reconstruction and support to the central government – the principle of military engagement in humanitarian operations in certain circumstances (Runge, 2009). The issue was further publicised last year by International Security Assistance Forces (ISAF) press release emphasising that:

“ISAF is also directly involved in facilitating the development and reconstruction of Afghanistan through Provincial Reconstruction Teams throughout the country” (NATO Annual Report, 2011).

4. The NGHAs perspective on PRTs

In order to assess the present civil-military cooperation trend in Post-Taliban Afghanistan, it is very essential to examine the perception of NGHAs on the involvement of PRTs in delivering aid. As discussed above, the establishment of PRTs in Afghanistan has seriously increased the discontent of the NGHAs operating in Afghanistan under the international humanitarian principles. One of the commentaries made by NGHAs and further supported by ICRC is the issue of blurring line between the responsibilities of military and NGHAs in most of the local Afghan communities. The ICRC, while criticising this trend, described the “blurring line” phenomenon as follows:

“The distinction between humanitarian, political and military action becomes blurred when armed forces are perceived as being humanitarian actors, when civilians are embedded into military structures, and when the impression is created that humanitarian organizations and their personnel are merely tools within integrated approaches to conflict management” (Rana, 2004, p. 586).

In another scenario, the simultaneous dropping of bombs and aid packages by the US military in 2001, which were later justified as military relief operations, is another instance showing how has the line between responsibility and identity of military and civilian humanitarian actors been blurred. This situation manifests that the civil-military cooperation has been affected and weakened from the very beginning, after the international community and coalition forces intervened in Afghanistan.

Furthermore, the uncoordinated humanitarian interventions, launched and implemented by PRTs, have contributed in endangering the lives of NGHAs aid workers in many ways. The civilian divisions of military teams, for instance, have made it difficult to physically distinguish the military personal from the aid workers. This ambiguity has led the insurgents to target NGHAs staff, quite frequently assuming them as military. Similarly, when the UN Under-Secretary General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, John Holmes, visited Afghanistan in June 2008, he expressed:

“I agree that there has been and there is to some extent a blurring of lines between military operations and, for example, humanitarian assistance by the PRTs. I think it is very important that PRTs do not involve themselves in humanitarian assistance unless there is absolutely no other alternative for security reasons” (Runge, 2009).

However, such emphasis never proved effective for convincing PRTs to terminate their relief operations.

At this point, the essay outlines four specific areas where NGHAs have increasingly suffered from the instrumentalisation of humanitarian aid by the military, on the one hand, and the blurred line of responsibilities between civilian and military actors, on the other. The below sub-sections discuss how the current military approach towards the civil-military cooperation trend and the military involvement in development and humanitarian activities undermined the humanitarian principles, overlapped the implemented projects, fuelled the violence and finally reduced the space for humanitarian actors in most of the Afghan local communities to operate.

4.1. Undermining humanitarian principles

Humanitarian aid is based on the principles drawn in the humanitarian code of conduct in which all NGHAs are committed to act accordingly. The essence of these principles – Humanity, Neutrality and Impartiality – is to deliver humanitarian assistance to the vulnerable and needy population regardless of race, ethnic, nationality and political background. Since the PRTs are deployed in Afghanistan for a military and political purpose, therefore; they cannot be perceived as humanitarian actors. The humanitarian actors expressed their concerns continuously about the issue. Save the Children Fund, for instance, declared the humanitarian involvement of military as: “inappropriate and contrary to the fundamental humanitarian principles of independence and impartiality” (Hugh, 2004). Some may argue that the military occupying power has a mandate to ensure the safety and security of the civilian population or NGHAs in the unstable and unsecure environments based on International Humanitarian Law and the 4th Geneva Convention. This never means that the occupying military power can deliver humanitarian aid directly, nor it can legally justify involvement of military in relief operations. In contrast, the present military involvement in delivering humanitarian and development assistance is in violation of international humanitarian principles.

In another instance, a press release by NATO/ISAF on December 2007, declared that: “Humanitarian assistance operations are helping both the people of Afghanistan and coalition forces to fight the global war on terror” (ISAF, 2007). The integration of humanitarian assistances with a political agenda of war on terror has significantly undermined the principle of neutrality of NGHAs among the local Afghan population. Moreover, according to Donini (2009, p.2) ICRC is the only international organization that is able to operate neutrally, impartially and independently on both sides of the warring parties. However, thousands of NGHAs are operating in Afghanistan after the fall of Taliban.

4.2. Overlapping interventions

In principle, the roles and responsibilities of PRTs and NGHAs are sharply different, however; in practice these responsibilities are extremely blurred. Under this circumstance, development and humanitarian actors have expressed their concerns about the overlapping of certain implemented projects in the field (Hugh, 2004).

An assessment conducted by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) on Security of ADB Projects in Afghanistan in 2007 revealed a couple of substantial PRT interventions that contradict Article 32.4 of the United Nations Guideline for Civil-Military Cooperation. Here, the paper quotes some of the ADB assessment findings:

“Some PRTs include projects linked to health care, education, water supply or waste clearance, in this, there is an overlap with NGO programmes” (Marsden & Arnold, 2007; p.30)

“There is some evidence that some PRTs have provided cash to power holders or individual villagers in an effort to win influence” (Marsden & Arnold, 2005; p.31).

“Some PRTs, including those led by Spain and Italy, use military personnel for development work” (Marsden & Arnold, 2007, p.30).

As a result of PRT’s constant intrusions without respecting the enacted civil-military cooperation guidelines, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Aid (UNOCHA) described the increasing influence of military in humanitarian activities as follows:

“In NATO and elsewhere there has been an evolution of the doctrine of military–civilian operations, with an increasing tendency for military forces being used to support the delivery of humanitarian aid, and sometimes even to provide this aid directly (Barry and Jefferys,2001, p. 1).

Moreover, another critique against the PRTs involvement in the development and humanitarian sphere is their unprofessionalism. The military actors are not well-trained to implement complex cross-cutting and mutually reinforcing projects at the community level. This awkwardness is bolded in the areas of rebuilding the political institutions and effectively engaging with civil society actors (Jenny, 2007).

4.3. Fuelling violence

Increased violence against humanitarian aid workers is another consequence of the current ineffective civil-military cooperation in Post-Taliban Afghanistan. In the list of fragile countries where the level of violence against aid workers is enormously high, Afghanistan is positioned in third place. Relief operations by PRTs notably raised acts of violence against NGHAs. In 2004, for instance, five employee of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) were targeted and killed by insurgent. As a result, MSF evacuated its staff and stopped operating in Afghanistan. Moreover, an assessment conducted by the German Institute for International and Security Affairs, revealed that the security environment in northern provinces of Afghanistan has deteriorated and level of violence against aid workers has increased since the deployment of the German Military (Lange, 2008). It is noteworthy that the northern provinces of Afghanistan were considered highly secured regions after the fall of Taliban regime.

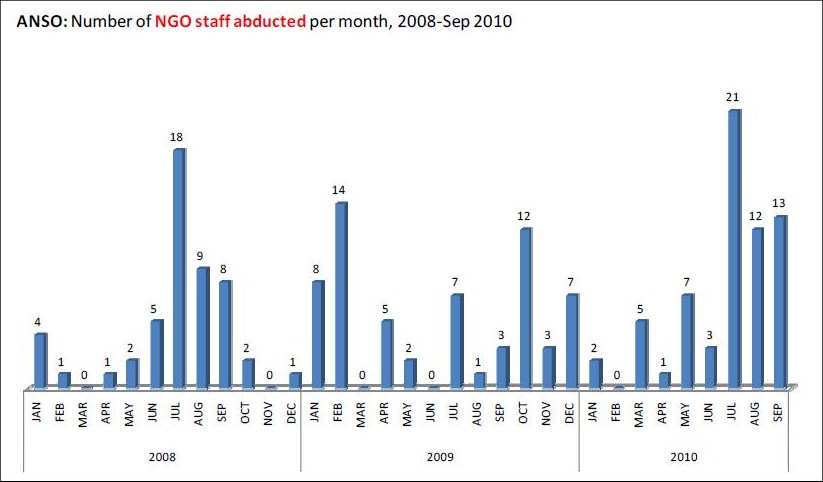

Appendix one is produced by Afghanistan NGO Security Organization (ANSO) which shows a 60% increase in the abduction of aid workers over the year 2009 (ANSO Annual Report, 2011). According to the Afghanistan NGO Safety Office (ANSO) the increased nature of insurgents’ attacks on NGHAs, are functionally linked with a misperception that NGHAs have political and military agendas (Cornish & Glad, 2008). Such views were strongly publicised by the various international high officials like Colin Powell, the former US Secretary of States, who said: “NGOs are the force multiplier” (Runge, 2007). Ultimately, the consequences of such publications were the death of 1500 civilians who were targeted by different insurgency attacks in 2010. Furthermore, a report by UNAMA contrasts the level of violence in 2001 with the level of violence in 2007. According to the report, in 2001 only 3 suicide attacks were carried out in Afghanistan, while after five years of international military presence in Afghanistan, this figure increased 53 times. In other words, 160 suicide bombing attacks were conducted by insurgents in 2006 (UNAMA, 2007).

4.4. Reducing Humanitarian space

The increased level of violence, discussed above, is a restricting factor for the presence of NGHAs in most of the local Afghan communities. Humanitarian actors need “Humanitarian Space” (Runge, 2007) in the conflict affected areas to independently and impartially identify conflict victims to assist them. This humanitarian space is getting limited, especially when PRTs interfere in providing aid by wearing civilian uniforms and driving unmarked vehicles in the local communities. This humanitarian nature of the military posed another serious threat to the security of NGHAs since there is no distinguishing indicator left between them and the PRTs. MSF, for instance, was among those NGHAs that found itself in an eroded humanitarian space. The justification given by MSF, after evacuating its staff and stopping all its operations in Afghanistan, was increased level of violence against their employees as a consequence of military involvement in providing humanitarian aid in the ground. In another instance, a UK quartered NGO left its projects and withdrew from Kamdesh District because a US armed team visited the community without informing the local authorities in advance and prior consultation with the NGO (Afghanistan Group, 2008, p. 22).

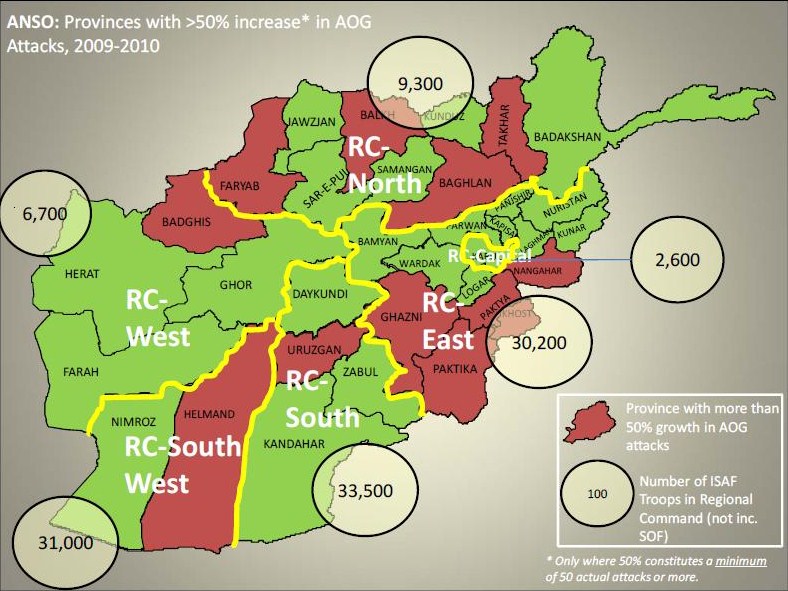

In appendix two, the figures shown in the circles are the total number of armed NATO forces in each province. Regions that are coloured in red means a 50% of growth in Armed Opposition Groups (AOG) attacks. It is interesting to see in Herat Province, for instance, the number of NATO forces is fewer – 6,700 forces – compared to Helmand – 31,000 forces – but still the level of violence in Helmand had a 50% growth over the year 2009. This shows that the presence of military in the local Afghan communities have contributed to the growth of violence.

To condemn the erosion of humanitarian space in Afghanistan, The Agency Coordinating Body for Afghan Relief (ACBAR) released a statement in 2007, mentioning that:

“Humanitarian actors are increasingly unable to provide adequate protection and assistance to displaced people and other populations at risk in the south and east of Afghanistan due to the significant deterioration in the security situation. Humanitarian space and humanitarian access continues to be seriously limited” (ACBAR, 2007).

Moreover, existence of great insecurity against the NGHAs significantly decreased the possibilities of accessing the needy population in most of the Afghan communities. Studies carried out by UNHCR and ICRC demonstrates that large part of the country is inaccessible by NGHAs. UNHCR claimed that in 2008, they only had access to 55% of the country and ICRC declared that the humanitarian access situation was the worst in the last 27 years in Afghanistan in 2008 (Norton-Tylor, 2008).

5. Theorising Civil-Military Cooperation in Post-Taliban Context: A key for improving

The Theory of Shared Responsibility, posed by Douglas L. Bland (1999) argues that Civil-Military Cooperation can effectively be improved by sharing responsibilities between civilian and military actors. Theory of Regime, which Bland (1999) borrowed from International Relations, provides a conceptual framework and strong instrument to arrange and maintain the shared responsibilities between the civilian and military actors. Theory of regime emphasises an evolved regime of norms, principles, rule and decision making procedures in order to restrict the actors to respect the rule of the game and operate within the limits of their responsibilities. Considering the results of above analysis on the present Civil-Military Cooperation trend in Afghanistan and its harmful implications on NGHAs activities, at this point, the paper takes a step forward, and utilizes Theory of Shared Responsibility (Blend, 1999) and Theory of Regime (Krasner, 1983) to sketch out the potential courses of action for improving Civil-Military Cooperation in the future humanitarian and development joint-efforts in Post-Taliban Afghanistan.

In order to address the legitimate concerns – as discussed above – of the NGHAs, caused by a deficient civil-military cooperation approach and a blurred line of responsibilities among the actors, the study strongly suggests a clear division of responsibilities between PRTs, represented by military, and NGHAs. To restrict the PRTs and NGHAs to operate according to their sharply distinguished roles, this paper recommends that a series of legitimate principles – accepted by both sides – should be enacted and reinforced by a third party from the top, preferably by a joint committee of humanitarian and military divisions of the United Nations (UN).

Considering the context of Post-Taliban Afghanistan, the study suggests that PRTs should restrict their role into two main areas: First, PRTs should concentrate in providing security in unsecure communities rather than delivering humanitarian or development aid in stable areas. It is frequently observed that presence of PRTs in stable communities has deteriorated the security situation rather than improving it. Secondly, PRTs engagement in humanitarianism should be transformed into a logistical backup only in humanitarian catastrophes or disasters. It is an obvious fact that in Post-Taliban Afghanistan, NGHA are in a better position to deliver humanitarian aid than the PRTs. Most importantly, PRTs should immediately terminate and handover their interventions in the areas of education, water and food aid to NGHAs (Sedra, 2005).

The Civil-Military Cooperation model, proposed above, will allow NGHAs to access the conflict victims on time and effectively deliver the assistances to the affected communities. Moreover, this approach will contribute in enhancing community participation in delivering aid and will mitigate the hostilities, mistrust and suspicion between the local Afghan communities and international society.

In order to encourage civil-military academics and practitioners in dedicating their future research to finding alternatives and effective ways for improving the civil-military cooperation trend in Post-Taliban Afghanistan, the study ends up this section by quoting a short but meaningful sentence by Mary Anderson, the author of DO NO HARM: “…the range and variety of ways should be identified, in which international assistance worsens the situation rather than relief” (Anderson, 1999).

6. Conclusion

The essay sought to examine the Civil-Military Cooperation trend in Post-Taliban Afghanistan. The results of this study revealed that Non-governmental humanitarian agencies (NGHAs) are increasingly suffering from the present deficient Civil-Military Cooperation approach that was caused by enormous engagement of the military in relief operations, a blurred line of responsibilities between civilian and military actors and finally the instrumentalisation of humanitarian and development assistances in the favour of political and military purposes in Afghanistan.

To formulate its recommendations, the essay employed Theory of Shared Responsibility (Blend, 1999) and Theory of Regime (Krasner, 1983) and proposed a clear division of responsibilities between the civilian and military actors. Moreover, immediate termination of the present military relief operations in the areas of education, water and food aid, and handing them over to NGHAs was another recommendation suggested in this paper for improving Civil-Military Cooperation in Post-Taliban Afghanistan.

Appendix 1:

Appendix 2:

Bibliography

Anderson. M. B. (1999). Do No Harm: How Aid Can Support Peace or War. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers

BBC. (2011). 8 February 2011. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-south-asia-12400045 (Accessed 9 February 2012)

Blend. G.L. (1999). A unified theory of Civil-Military Relations. Armed Forces and Societies. Available at: http://afs.sagepub.com/content/26/1/7(Accessed 29 January 2012)

Brzoska. M. & Ehrhart. H. (2008). Civil-military cooperation in post-conflict rehabilitation and reconstruction. Development and Peace Foundation. Available at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/sede/dv/sede260410studyehrhart_/sede260410studyehrhart_en.pdf (Accessed 29 January 2012)

Cornish. S. & Glad. M. (2008). Civil-Military Relations: No room for humanitarianism in comprehensive approaches. The Norwegian Atlantic Committee. Available at: http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/C312D751A2DA554F852575B300577460-care-civil-military-jan09.pdf (Accessed 2 February 2012)

Dziedzic. M. & seidl. C. (2003). Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs) and military relations with international non-governmental organizations in Afghanistan. United States Institute of Peace. Available at: http://www.usip.org/publications/provincial-reconstruction-teams-military-relations-international-and-nongovernmental-organ (Accessed 02 February 2012)

Hugh. G. (2004). Provincial reconstruction teams and humanitarian-military relations in Afghanistan. Save The Children-UK. Available at: http://www.savethechildren.org.uk/resources/online-library/provincial-reconstruction-teams-and-humanitarian-military-relations-in-afghanistan (Accessed 05 February 2012)

Jenny. J. (2007). Civil-Military Cooperation in complex emergencies: Findings ways to make it work. European Security. Available at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09662830108407492#preview (Accessed 05 February 2012)

Krasner. D. (1983). Structural Causes and Regime Consequences: Regimes as Intervening Variables. In International Regimes, NY: Cornell University Press.

Krasner. S. D. (1983). International regimes. Ithaca. NY: Cornell University Press. Available at: http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=WIYKBNM5zagC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false (Accessed 25 January 2012)

Marsden. P. & Arnold. F. (2007). An assessment of security of Asian Development Bank projects in Afghanistan. Asian Development Bank (ADB). Available at: http://www.adb.org/Documents/Assessments/Other-Assessments/AFG/Conflict-and-Security-Assessment.pdf (Accessed 04 February 2012)

Norton-Tylor. R. (2008). Afghanistan’s refugee crises ‘ignored’. 13 February 2008. The Guardian. Available at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/feb/13/afghanistan (Accessed 03 February 2012)

ODI. (2006). Humanitarian Policy Group Briefing Paper. September 24, 2006. Available at: http://www.odi.org.uk/work/programmes/humanitarian-policy-group/activities-resources.asp (Accessed 20 January 2012)

Rana. R. (2004). Contemprory Challenges in the civil-military relationship: Complimentarity or Incompatibility?. IRRC. Available at: http://www.icrc.org/eng/assets/files/other/irrc_855_rana.pdf (Accessed 03 February 2012)

Runge. P. (2009). The provincial reconstruction teams in Afghanistan: Role model for civil-military relations?. INTERNATIONALES KONVERSIONSZENTRUM BONN. Available at: http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/reliefweb_pdf/briefingkit-a298f807bf479dff36042d74a3f61c0f.pdf (Accessed 02 February 2012)

Sedra. M. (2005). Civil-Military Relations in Afghanistan: The provincial reconstruction teams debate. The Canadian Institute of Strategic Studies. Available at: http://www.opencanada.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/SD-126-Sedra.pdf (Accessed 02 February 2012)

The ACBAR Annual Report. (2007). Afghanistan: NGO Voices. Available at: http://reliefweb.int/taxonomy/term/409 (Accessed 25 January 2012)

The ANSO Report. (2011). The Afghanistan NGO Safety Office. Available at: http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/The%20ANSO%20Report%20%2816-30%20June%202011%29.pdf (Accessed 05 February 2012)

UNAMA Annual Report. (2011). Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict. Available at: http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/AF/UNAMA_Feb2012.pdf (Accessed 08 February 2012)

Weiss. T.G. (1999). Military-Civilian Interactions: Intervening in humanitarian crises. New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

[1] For more information about NGHAs, please refer to page six of this document or click to: Non Government Humanitarian Agencies (NGHAs)

[2] For more information about PRTs, please refer to page six of this document or click to: Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs)

—

Written by: Ramin Shirzay

Written at: The University of York

Written for: Post-war recovery studies

Date written: 02/2012

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Beyond Good and Evil: The Sources of US Strategy in Post-Invasion Afghanistan

- A Critical Analysis of Libya’s State-Building Challenges Post-Revolution

- No Peace Without Justice: The Denial of Transitional Justice in Post-2001 Afghanistan

- The Impact of the Rise of Islamic Extremism on Civil-Military Relations in Indonesia

- A Critical Analysis of The Exclusion of the State in Terrorism Studies

- “In sight of surrender”: Critical Analysis of the 2022 Sanction Regime on Russia