This is a shortened version of the article ‘Establishing a new Global Economic Council: governance reform at the G20, the IMF and the World Bank‘, which first appeared in Global Policy in May 2012.

—

Whatever the miseries in its wake, the 2008 global economic crisis at least served to persuade the G7 heads of government that they must consult regularly with heads of government of some developing economies. Otherwise, the G7 would be like the captain of a ship who stands at the wheel turning it this way and that – knowing that the wheel is not connected to the rudder.

First convened in November 2008, the G20 leaders soon designated themselves ‘the premier global economic forum’. Now, more than three years later, they claim three major successes in steering the world economy:

- financial regulation, especially the Basel III Accord on bank regulation

- macroeconomic policy coordination through the ‘framework for strong, sustainable and balanced growth’

- governance reforms of the Bretton Woods organizations

If only. Their claims barely survive scrutiny. Martin Wolf of The Financial Times describes the Basel 3 agreement as a ‘mouse’ (Wolf 2010); and 20 distinguished finance professors protested in an open letter to The Financial Times that Basel III is ‘far from sufficient to protect the system from recurring crises’ (Admati et al 2010). On macroeconomic policy coordination, the G20 claims ‘great progress’ in dealing with global imbalances, but ‘semi-paralysis’ is a better description (Chin 2011); or in the slightly more upbeat words of The Financial Times’ Chris Giles, ‘the G20’s progress in reducing global imbalances inches forward at glacial speed’ (Giles 2011). And the results of the governance reforms of the Bretton Woods organizations are so small in scale and scope and distinct from the ‘dramatic improvement’ of global governance claimed by the G20 (see below, and Vestergaard and Wade 2011a). In short, the G20 has proved as far from effective as Greece is from solvency.

The problem is not only that the G20 has had trouble living up to its ambitions. The G20 also fails to meet widely accepted criteria of representational legitimacy. Its members beyond the G7 were selected by the G7 on the basis of no clear criteria. For example, it does not include the 20 largest economies by GDP, and quite a few of the members could not possibly be described by the G20’s own avowed criterion, ‘systemically important’. Moreover, the G20 permanently excludes 90% of the 193 member states of the United Nations, their exclusion softened only a little by the ad hoc inclusion of representatives of some regional organizations as observers. It thus reinforces a trend towards ‘multilateralism-of-the-big’ (MOB), in which the vast majority of nations lose a voice on matters that may affect them crucially, because of the lack of a representational system.

A third problem is that, insofar as the self-elevated G20 takes upon itself the role of ‘the premier global economic forum’, it weakens the existing system of multilateral cooperation in organizations such as the IMF, the World Bank and the United Nations, causing resentment among the staff and among non-G20 member countries (Bosco 2010) – as though the G20 had carried out a ‘coup by stealth’.

Fourth, the G20 is just a ‘talk shop’. There are good reasons to aspire to an apex governance body with some real authority, such as through strategic direction-setting for the Bretton Woods organizations.

This paper describes an alternative economic governance body to replace the G20, which has a firmer constitutional foundation. We recognize that the idea of replacing the G20 with a newly-constituted Global Economic Council is a ‘pie in the sky’, in the absence of any sign that excluded actors might mobilize around an agenda of major reform. But it would be foolish to wait for such signs before debating alternatives. If the G20 proves unable to coordinate major reforms to financial systems and demand generation systems, as we think likely, multi-country financial crises will continue to roil the world economy at a frequency of roughly every five years. They will provide ample opportunity for new governance designs elaborated on the margins to come galloping in to now more sympathetic central venues.

Establishing a global economic council

A promising design for what we call the Global Economic Council (GEC) starts from the existing Bretton Woods system of representation.[1] Whatever one may otherwise think of these organizations in terms of their lending policies, etc., few would disagree that they are reasonably well-functioning multilateral organizations, a crucial public good, and in desperately short supply. A key reason for their relative success is, we argue, the way representation and effectiveness is balanced in their governing bodies. The country constituency system of the Bretton Woods organizations is simply the best model around to ensure input legitimacy (representation) without compromising output legitimacy (effectiveness). For this reason, the Bretton Woods system is a good place to start. However, the Bretton Woods organizations have their own problems which must be addressed. The two main deficiencies of the Bretton Woods system are:

- The absence of a Leaders’ forum, which causes the Bretton Woods organizations to suffer from a lack of ‘political weight’.

- Its voting power systems, which do not adequately recognise the increased economic and political weight of dynamic emerging market economies.

The proposed Global Economic Council and accompanying reforms of country constituencies and voting power systems addresses both these deficiencies.

We see the proposed model as one that is ‘universal’ in the sense that it could, in principle, be adopted as the governance structure for a range of global governance bodies. Hence, we propose the Global Economic Council as a body that has a steering role over the Bretton Woods organizations, as well as deliberates on other issues of global economic governance, much as the G20 has done in recent years. While the Bretton Woods system serves as our model in terms of the constituency system, there is no reason why its mandate should be confined to the mandates of the Bretton Woods organizations.

It is important that the constituencies for the GEC are the same as for the governing bodies of the Bretton Woods organizations. This paves the way for the GEC to exercise some real authority, not least by displacing the G7 states from their continuing role of, as Kemal Dervis says, ‘strongly influenc[ing] the operational management of the Bretton Woods institutions, thereby sidelining the much more ‘global’ Executive Boards and crossing the line between governance and the management of day-to-day operations’ (Dervis 2005: 86). If the Global Economic Council does not take over this ‘steering role’ from the G7, fundamental legitimacy problems would remain: many in developing countries would see the Bretton Woods organizations as still beholden to Western interests, and the new Global Economic Council as merely an extension of the old order, rather than the beginning of a new one.

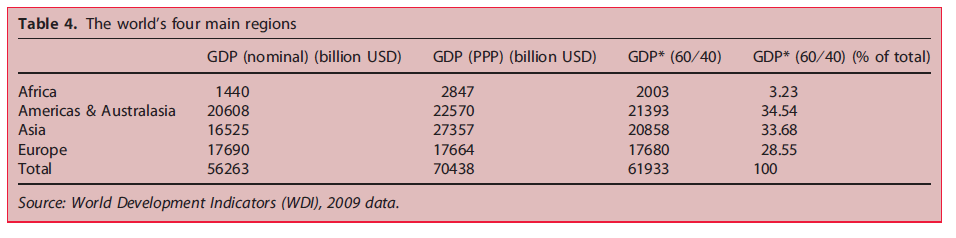

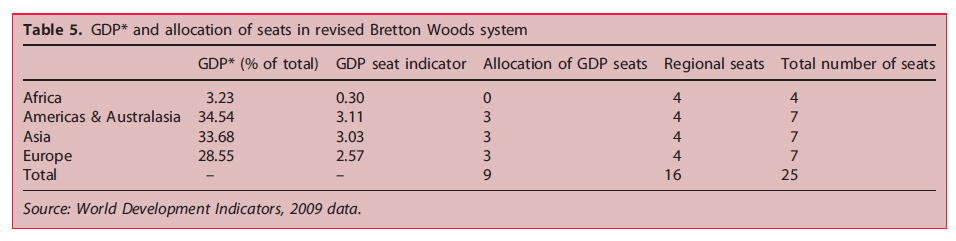

We propose that the GEC should have 25 seats, with 16 seats allocated equally to the world’s four main regions – Africa, Americas, Asia and Europe – and nine seats allocated on the basis of aggregate regional GDP.[2] Table 4 shows the economic weight of these regions by several measures of GDP.

Why 25 members? Why not fewer or more? We suggest 25 seats for several reasons. First, fewer than 20 is not compatible with input legitimacy (some country constituencies would be too large) and more than 30 could easily jeopardize deliberation and, hence, output legitimacy. Second, the country constituencies of the Bretton Woods organizations – which have functioned reasonably well for decades – consist of 24 and 25 seats respectively. Third, in order for regional seats to constitute (roughly) two thirds of total seats, and be divisible by four, there are two options: 16 regional seats and 8-10 GDP seats, or 20 regional seats and 9-11 GDP seats. The former option has the best fit with the stated criteria.

Why should two thirds of seats be regional? Allocating double the amount of seats on a regional basis as compared to seats allocated on GDP basis sends an important signal of the new multipolar order.[3] Why 25, instead of 24 (which would correspond to exactly two thirds)? Because this gives all three regions other than Africa an equal amount of seats (at current levels of GDP), which could be instrumental in getting their support.

With sixteen seats in the council distributed equally among each of these four main regions, and nine additional seats assigned to the four regions in proportion to their share of world GDP, Africa would get four seats and the three other regions seven seats each. See Table 5.

Instead of tweaking the existing Bretton Woods constituencies, what would they look like if rethought from the beginning? What new principles should guide the allocation of chairs within regions to apply to both the Bretton Woods organizations and the new GEC?

Allocation of seats within regions

Within the four main regions, assignment of states to chairs should be based on the following six steps.

First, governments within each region negotiate to form constituencies, with a minimum of three and a maximum of 17 countries in each. Size restrictions are needed to balance the interests of big powers (US, China, etc.) in limiting the number of countries in their constituency, with the general interest in limiting the average and maximum size of the remaining constituencies.[4]

Second, constituency size falls into two categories: ‘narrow’ ones (three countries) and ‘broad’ ones (five to 17). For each narrow constituency, there must be at least two broad ones. This criterion means that there can be no more than two narrow constituencies in Asia, Europe and Americas+, and only one in Africa.

Third, the first round of the ‘election’ invites nominations for narrow constituencies. Which of the nominated groups get the region’s one (Africa) or two (Americas+, Asia, Europe) narrow country constituency seats is established on the criteria of biggest aggregate GDP.

Fourth, the second round of the election invites nominations for ‘broad’ constituencies. After the narrow constituencies are accounted for, the remainder of a region’s seats minus one are now allocated among the nominees on the basis of biggest aggregate GDP. In Asia, Europe and Americas+, this means that four seats are allocated to the four biggest of the nominated ‘broad’ constituencies. In Africa, two seats are allocated to the two largest of the nominated ‘broad’ constituencies.

Fifth, country constituencies which did not get ‘elected’ in this second round of the process are now grouped into the final seat of each region, reserved for this purpose.

Sixth, all countries within a constituency may put forward candidates for the chair. The chair is chosen in an election with votes allocated to constituency countries in line with relative GDP. Constituencies would be obliged, however, to institute a mechanism of rotation to ensure consultation and dialogue within the group. Each constituency would have one executive director and one or two deputy directors, and could decide internally whether there should be rotation at both levels or only at deputy level. This flexibility in rotation modalities allows large economic powers – such as the US, Japan and China – to be permanently in the chair of their constituency, but still in consultation with and to a degree answerable to at least two other states.[5]

At periodic intervals (say, every five years) new negotiations for constituencies should be held.

Europe

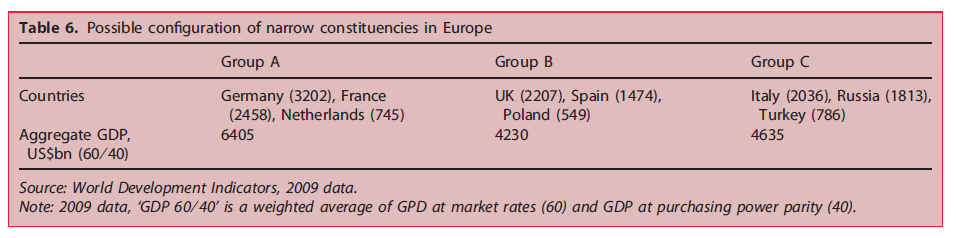

To illustrate how the election would work, consider the case of Europe. In the first round, when countries compete for the narrow constituency seats available for their region, several different three-country alliances might nominate themselves.[6] Suppose there are three, as shown in Table 6.

Germany, France and the Netherlands would win one of the two European narrow seats, while the UK, Spain and Poland would see themselves marginally defeated by Italy, Russia and Turkey. Obviously, the process of negotiating these alliances and the ‘election’ would, for all practical purposes, be one and the same thing. In the example given, the UK would be aware that the alliance proposed here might prove too weak if Italy, Russia and Turkey were to team up – and would therefore try to form a stronger alliance. It could, for instance, attempt to seduce Italy. But if Group A and Group C had already formed, there would be little the UK could do to ensure membership of a narrow seat. Of course, this could happen to any of the big European powers, depending on how the negotiation process unfolds.

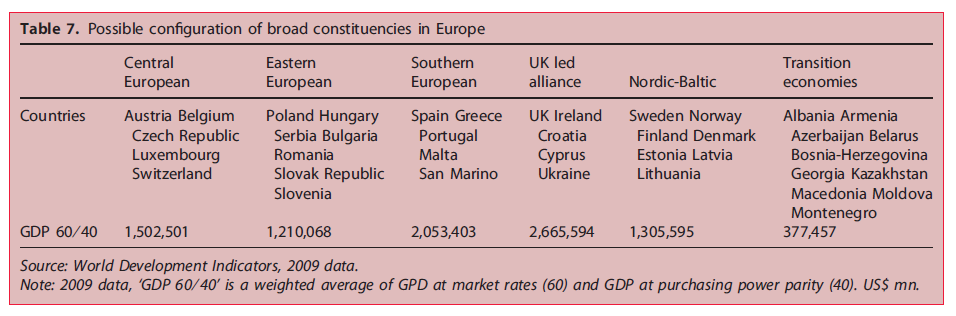

After the election of two narrow seats, alliances would be formed in competition for the four broad seats (five to 17 countries) to be allocated in the second round (see Table 7). The Nordic-Baltic countries might nominate themselves for a broad seat, in competition with, say, five other alliances: a Central European alliance; an Eastern European alliance; a Southern European alliance; an alliance formed around the UK; and an alliance of European transition economies.

In the second round, the four largest of these six broad constituencies would be elected, and the two defeated constituencies would be grouped in a shared constituency in the third and final round to take up the last European seat. At current levels of GDP, the four largest of these six constituencies would be the UK-led, the Southern European, the Central European and the Nordic-Baltic constituencies – and hence the Transition- and Eastern European constituencies would be grouped into the seventh and last European constituency.

Conclusion

Defenders of the G20 dismiss the kind of proposals made here as mere ‘formalistic recipes’ and ‘conceptual thinking’ (Cooper 2011: 208). Their own proposals for G20 reform take the existing full members as given and add on guest representatives from some regional organizations in order to overcome the ‘representational gap’. They are the hunters in the Swahili proverb: ‘Until the lions have their own historians, tales of hunting will always glorify the hunters’.

We argue that the G20 scores low on both effectiveness and legitimacy, in substantial part because it has no – or almost no – representation of the 174 member-states of the United Nations which are not invited to participate. The basic problems are: (1) the current membership of the G20 was selected on the basis of no explicit criteria; (2) there is no mechanism for adding and dropping countries as relative economic weight changes over time; and (3) there is no mechanism of universal representation, such that all states are incorporated into a representational structure.

We have argued that a Global Economic Council should be established, based on a constituency system as known from the Bretton Woods organizations (the World Bank and the IMF). But instead of tweaking the existing Bretton Woods constituencies, country constituencies should be rethought from the beginning.

We propose that both the Bretton Woods governing bodies and the Global Economic Council should comprise 25 country constituencies, and that the world should be divided into four main regions (Africa, the Americas and Australasia, Asia, and Europe). The seats should be allocated so as (1) to ensure significant representation of all the main regions, and (2) differentiation between regions on the basis of their aggregate GDPs.

The major advantages of the proposed reconfiguration of global economic governance are that:

(1) It would embed a leaders’ council within the institutional framework of the existing Bretton Woods organizations, while at the same time bringing the latter up to date; resulting in congruence between the structure of the pinnacle agenda-setting body and the more operational bodies over which it has stewardship.

(2) It would reconfigure the current country constituencies, so that all chairs represent at least three and no more than 17 member countries.

(3) It would give long-term durability to global economic governance, because the system responds to the rise and fall of nations and regions through a transparent, automatically updated system of weighted voting (based on GDP), while ensuring at the same time a certain level of inter-regional legitimacy and stability by means of the proposed balanced allocation of chairs to all the world’s regions.

We have laid out an organizational model which allows a better balance between established and rising powers, a more durable way of changing the governing balance as the economic balance changes, and a full institutionalization of the principle of universal representation. The G7 states themselves are no more likely to push in this direction than turkeys are to vote for Christmas, but that should not stop others from advocating along these lines.

—

Dr. Jakob Vestergaard is Senior Researcher and Head of Research Unit on Global Economy, Regulation, and Development at the Danish Institute for International Studies, Copenhagen, Denmark. He is the author of Discipline in the Global Economy? International Finance and the End of Liberalism (Routledge, 2008).

Prof. Robert H. Wade is a Professor of Political Economy and Development at the London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK.

Bibliography

Admati, A. R., et al. (2010) ‘Healthy banking is the goal, not profitable banks’, Financial Times, 9 November. Available from: http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/63fa6b9e-eb8e-11df-bbb5-0144feab49a.html#axzz1kGdcAKwY [Accessed 23 January 2012].

Bosco, D. (2010) ‘Who’s afraid of the G20? ’ The Multilateralist, 28 September. Available from: http://bosco.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2010/09/28/does_the_g_20_need_a_secretariat [Accessed 23 January 2012].

Chin, G. (2011) ‘Global imbalances: Beyond the ‘‘MAP’’ and G20 stovepiping’, CIGI Commentaries. Toronto: Centre for International Governance Innovation.

Commission on Global Governance (1995) Our global neighbourhood.New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Cooper, A. (2011) ‘The G20 and its regional critics: the search for inclusion’, Global Policy (forthcoming).

Dervis, K. (2005) A better globalization. Legitimacy, governance and reform. Center for Global Development, Washington DC.

Giles, C. (2011) ‘Dark outlook piles pressure on leaders’, G20 Summit, Financial Times, 3 November. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/a85142c4-ffef-11e0-ba79-00144feabdc0.html [Accessed 22 January 2012].

Ocampo, J.A. (2010) ‘Rethinking global economic and social governance’, Journal of Globalization and Development, 1 (1).

Stiglitz, J., et al. (2009) ‘Report of the Commission of Experts of the President of the United States General Assembly on Reforms of the International Monetary and Financial System’. New York, NY: United Nations.

ul Haq, M. (1995) An economic security council. IDS Bulletin, 26 (4):20–27

Vestergaard, J. and Wade, R. (2011a) ‘Adjusting to multipolarity in the World Bank: ducking and diving, wriggling and squirming’. DIIS Working Paper, 2011: 24. Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies.

Vestergaard, J. and Wade, R. (2011c) ‘The new Global Economic Council: governance reform at the G20, the IMF and the World Bank’. DIIS Working Paper, 2011: 25, Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies.

Wolf, M. (2010) ‘Basel: the mouse that did not roar’, Financial Times, 14 September. Available from: http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/966b5e88-c034-11df-b77d-00144feab49a.html#axzz1kGdcAKwY [Accessed 23 November 2012].

Zedillo, E., et al. (2001) Report of the High-Level Panel on Financing for Development. New York, NY: United Nations.

[1] For other literature on the idea of an apex global economic governance body, see Dervis (2005), Ocampo (2010), and ul Haq (1995). For high-level endorsements, see the Commission on Global Governance (1995), the Zedillo Commission (2001), and the Stiglitz Committee (2009).

[2] We divide the world into these four regions to achieve homogeneity of size, both in terms of population and in terms of GDP. We start from the five world regions used in UN classifications: Africa, Americas, Asia, Europe and Oceania. The latter of these regions we split and integrate in two of the other regions: Australasia (Australia, New Zealand, New Guinea and neighbouring islands) with the Americas, and the rest of Oceania with Asia. In this way we arrive at four regions that are relatively homogenous in terms of GDP (except Africa) and population (except Asia).

[3] Organizationally, the Global Economic Council should have four regional headquarters – one for each of the four world regions – with hosting of summits rotating between them. This would reinforce the symbolically important signal that the Global Economic Council marks a new era of genuinely multipolar global economic governance – rather than just the continuation of the old system, in new guises.

[4] For more on the logic of the size constraints of country constituencies, see Vestergaard and Wade (2011c: 16-21).

[5] In polarized country constituencies, comprised of large countries together with small countries, the larger countries could choose to rotate the directorship while the smaller countries rotate at the deputy level.

[6] In Asia, the obvious major candidates for the two narrow constituencies would be China and Japan, but if India, South Korea and Indonesia were to make an alliance they would be a strong contender; Japan would find it hard to build as strong an alliance. In the Americas, the alliance formed by the US would get one of the narrow constituencies (irrespective of which two countries joined the US). A South American alliance (Brazil, Mexico, Argentina) and an Anglo-American alliance (Australia, Canada, New Zealand) might form in competition for the second narrow constituency. At current levels of GDP, the South-American alliance would win. Seeing this, Australia and Canada would then have to decide whether to form a joint broad constituency, two separate broad constituencies, or persuade the US to form a strong constituency consisting of the US, Canada and Australia.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Low-Cost Institutions: The New Kids on the Global Governance Block

- Global Governance: Political and Economic Governance

- Global Governance and COVID-19: The Implications of Fragmentation and Inequality

- Opinion – Coronavirus and the Need for Global Governance

- Rebranding China’s Global Role: Xi Jinping at the World Economic Forum

- How NGOs Shape Global Governance