Introduction

While many are aware of the ongoing unstable political, economic, and social crises in the West African state of Guinea-Bissau, theories abound around the root causes of its obstinacy. It seems as if there is, at best, a lukewarm response to these incidents from the international community. Tellingly, in his discussion of the most recent coup, one prominent Guinea-Bissau scholar called for “clear and knowledge-based analysis + prudent action” (personal communication, May 22, 2012, italics mine).[1] While he goes on to clarify “prudence” as “avoiding further confusion”, the word choice also axiomatically evokes sentiments of caution, wariness, and circumspection; this type of call to action concerning Guinea-Bissau is becoming commonplace in diplomatic, development, and academic discourses.[2]

Media headlines reinforce this disavowal: “Forty Spanish vessels no longer fish in Guinea Bissau”, “Falling cashew exports raise hardship”, and “Guinea-Bissau Is Suspended by African Union”.[3] The uninspired global reactions to the 2012 Guinea-Bissau coup d’état are the result of cyclical political unrest leading to stakeholder fatigue and long-term underdevelopment. This argument is not new.[4] However, recent political and economic indications show that what in fact may be taking place in Guinea-Bissau is not so much international apathy toward a seemingly inevitable march to failed statehood, but rather a realignment of partnerships from the West to alternative bilateral and multilateral partners such as BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, Indian, and China). This ongoing shift may be responsible for the internal ripples in that country’s political, economic, and social fabric.

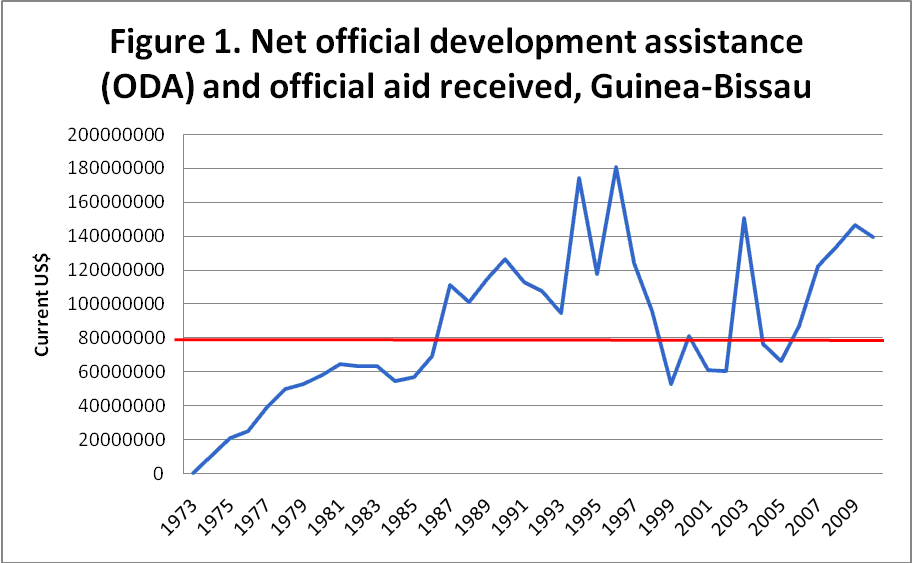

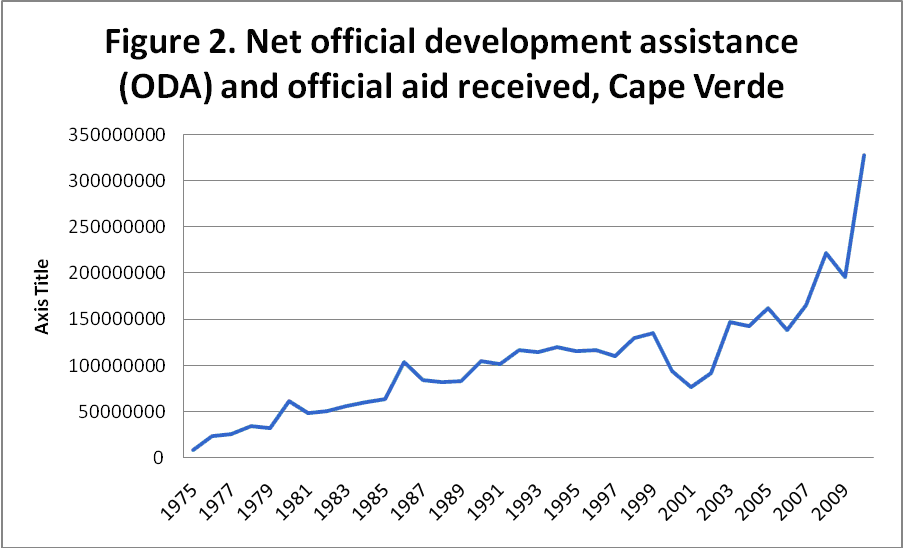

The first task is to demonstrate a lack of international interest in Guinea-Bissau from a Western perspective. It seems reasonable to operationalize “international interests” as development assistance and aid from outside sources, i.e., money. Therefore, one would hypothesize that international interest would be reflected in a steady increase in development assistance and aid over time while stagnation, dramatic shifts, or a decrease in funds would suggest disinterest or inconsistent interest on the part of the Development Assistance Community (DAC).[5] As Figure 1 demonstrates, the average amount of official development assistance (ODA) and aid averaged more than $85 million per year over a 37-year period.[6] During this time, ODA and aid increased over 21 years, decreased for 16 years, and was less than average for 20 years and above average for 18 years. This suggests inconsistent investment in institutional capacity building in Guinea-Bissau on the part of DAC. On the other hand, Guinea-Bissau’s sister republic, Cape Verde, showed a more uniform increase in ODA and aid as would be expected in a country attracting the positive attention of the international community (Fig. 2).[7]

SOURCE: http://data.worldbank.org/country/guinea-bissau, 2012

SOURCE: http://data.worldbank.org/country/guinea-bissau, 2012

SOURCE: http://data.worldbank.org/country/cape-verde, 2012

SOURCE: http://data.worldbank.org/country/cape-verde, 2012

Perseverance or Preservation: Chronic Political Instability

For decades, domestic non-governmental organisations (NGOs), external development programs, and investors in Guinea-Bissau have experienced lackluster results for a variety of reasons including political instability, poor infrastructure, unstable funding, and corruption.[8] Without noticeable returns on investments in the form of profits or measurable improvements in the quality of life and institutional capacity, more and more stakeholders are disavowing themselves from further speculation and state-building exercises in the country. For example, the Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP) mission “EU SSR Guinea-Bissau” in operation since June 2008 terminated operations on September 30, 2010 after constitutional order was unable to be restored following the April 1, 2010 mutiny in which Deputy Chief of Staff António Indjai overthrew army Chief of Staff Zamora Induta and briefly arrested the then-Prime Minister Carlos Gomes Júnior.[9]

The 2012 Guinea-Bissau coup d’état marks the sixth successful ouster of state leadership since independence was declared from Portugal in 1973.[10] No president has successfully served a full mandate. Unsuccessful military putsches in Guinea-Bissau are even more commonplace, with the military constantly meddling in state affairs. “Forças Armadas Revolucionárias do Povo (FARP) is the major locus of power in Guinea-Bissau, operating through the logic of coercion and force, and playing the role of modern kingmaker” (personal communication, May 24, 2012).[11] The April 12, 2012 coup followed the first round of presidential elections slated due to the death of President Malam Bacai Sanhá. The African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC) candidate and former Prime Minister Carlos Gomes “Cadogo” Júnior was the frontrunner; a group of soldiers calling themselves the Military Command toppled the government just two weeks before the second round run-off.[12]

Analysis of the coup showed that Cadogo was largely anathema to the military due to his unpopular stance on Security Sector Reform (SSR) being carried out in partnership with the Angolan MISSANG mission that created geopolitical tension with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).[13] He also aligned with the West to stop drug trafficking through Guinea-Bissau from South America into Europe, which the military is known to be associated with.[14] However, the discord was also related to Cadogo’s thug politicking, economic interests in natural resources, rampant cronyism, and underlying historical and structural problems including an increasing gap between the proletariat and ruling class due to structural adjustment programs (SAPs). These SAPs were implemented largely in the 1990s through privatizing public enterprises, which made a few such as Cadogo quite wealthy, while the majority suffered through severe austerity measures.[15]

The coup resulted in international condemnation led by the United Nations (UN) Security Council and African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council. Guinea-Bissau was suspended from the AU and ECOWAS, shortly to be reinstated in the latter. Eventually, a handpicked National Unity Government made up of a 27-member cabinet under Prime Minister Rui Duarte Barros and Interim President Manuel Serifo Nhamadjo was announced in order to transition back to a civilian government along with the deployment of ECOWAS peacekeeping troops to replace the outgoing MISSANG mission.[16] The European Union (EU) has called for concerted international action between the AU, ECOWAS, the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP), the UN, and the EU to restore constitutional order, continue SSR, and renew the fight against drug trafficking that is plaguing the country.[17] However, with the illegitimate temporary government in place, the country is quickly returning to business as usual, which is not necessarily positive.[18]

A Risky Investment

Guinea-Bissau is a country with few natural resources (principally timber, bauxite, fish, agricultural products). Its GNI per capita terms is one of the lowest in the world ($600), and its International Human Development Index (HDI) is 176th out of 187 countries with comparable data. More than two-thirds of the population lives below the poverty line.[19] The economy depends mainly on fish and cashew nuts as its major exports. Additional investment deterrents in the country include a small population, an unskilled labor force, poor infrastructure, small markets with little foreign capital, population and linguistic heterogeneity, and poor global exposure with negative coverage by the media (e.g. labeled as a Narco-state).[20]

Therefore, two significant economic outcomes from the April 2012 coup in Guinea-Bissau demonstrate the continued Ping-Pong match between international partners and the country’s economic initiatives. First, the EUR 9.2 million annual fisheries agreement between Guinea-Bissau and the EU set to go into effect was suspended on June 16 2012. This three-year deal was abandoned since it became impossible to guarantee the security of the European ships fishing in Guinea-Bissau’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ).[21]The coup is also responsible for halving cashew exports with more than 120,000 tons of cashews awaiting buyers. This is significant because Guinea-Bissau consistently ranks in the top 10 world exporters of raw cashew nuts every year. These exports bring the country more than $60 million annually making up almost 90 percent of the country’s income while the sector employs almost 80 percent of the labor force.[22] Cashew plantations cover nearly half the country and Bissau-Guinean farmers now produce less than half their staple rice needs, opting to trade cashews instead. India, the top importer of raw cashew nuts, has increased domestic production and slashed imports. Increasing insecurity has also made buyers reluctant to travel throughout the country, and those that do are offering very low prices. Food insecurity is on the horizon in Guinea-Bissau with increased borrowing and inflation reaching into all sectors of the economy and pockets of the country’s population.[23]

Is this vicious cycle of military intervention, political ineffectiveness, and economic turmoil expected to continue in the future? Has the international community repudiated this West African enigma? From an American perspective, the U.S. Embassy Operations in Guinea-Bissau were suspended on June 14, 1998 amidst civil war and have not yet resumed, with U.S. foreign policy interests in that country now being administered from Dakar, Senegal.[24] The U.S. Peace Corps followed suit and has not returned, while other U.S.-based development agencies remained a bit longer. For example, it was not until the 2003 coup that Africare phased out their operations in Guinea-Bissau.[25] Put more forcefully, over a 35-year period (1976-2010), the United States sent annually approximately $3.8 million in bilateral aid to Guinea-Bissau totaling approximately $132.6 million. Over those same years, the United States invested more than double in the Republic of Cape Verde (~$282 million), which has one-third the population compared to Guinea-Bissau. In terms of perspective, the United States provided Iraq more than $11 billion in bilateral aid in a single year (2005) and Afghanistan close to $3 billion in 2010 alone.[26]

Non-Alignment to Re-Alignment

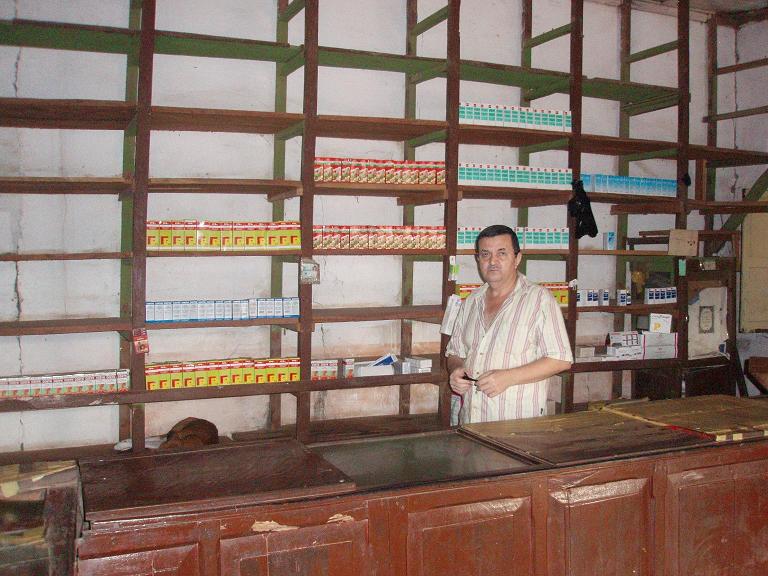

During the struggle for independence the PAIGC, under the leadership of Amilcar Cabral, maintained a policy of non-alignment, accepting assistance from Cuba, China and the Soviet Union as well as Sweden, Scandinavia, and the United States.[27] These sentiments persist with Guinea-Bissau diversifying its international investors, especially during times of crisis. While conducting ethnographic research in 2011 with the merchant class throughout Guinea-Bissau, for example, I found that the majority of shopkeepers were from Guinea Conakry, Senegal, Mauritania, Cote d’Ivoire, China, Lebanon, Libya, Pakistan, and India. These non-Western actors continue to have a significant impact on the country at both the local and national levels.

While the Angolan MISSANG mission aimed at reforming the army withdrew from the country in June 2012 amidst allegations of instigating the coup, Angola remains committed to investing in its CPLP partner. For example, in August 2012, the West African Economic and Monetary Union authorized a loan of 15 billion CFA francs to Guinea-Bissau to complete the deep-water port of Buba. This has allowed for the renegotiation of a bauxite deal with Angola Bauxite. The port at Buba would have the capacity to host three 70-tonne vessels providing for the export of up to three million tons of bauxite per year from Boe.[28] This is the continuation of a mining consortium project begun in 2006 involving companies from Switzerland, Austria, South Africa, and Norway.[29] Therefore, one of the largest private economic initiatives taking place in the country has not been stopped but re-aligned from a Western-centric consortium to interests from China and Angola.

Since the most recent coup in April, Guinea-Bissau has continued to seek new international partners. For example, in September 2012, Iran signed a cooperative Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with Guinea-Bissau to establish and enhance ties in all areas including economy and trade, education, agriculture, natural resources, and fisheries.[30] In addition, Vietnam has stepped in to buy up some of the cashews left behind by the Indian wholesalers who fled after the April coup, to meet export targets to the United States in China.[31]

According to World Trade Organization (WTO) data from 2010, Guinea-Bissau’s major export partners included India (86.6%), Singapore (12.1%), the EU (0.8%), and Panama (0.2%), while they relied on the EU (46.9%), Senegal (40.9%), Thailand (7%), China (2.4%), and Gambia (1.6%) for imports. The figures provided for 2011 showed similar export partners of India (41.5%), Nigeria (33.9%), Brazil (8.7%), and Togo (7.9%) while imports came from Portugal (28.3%), Senegal (15.6%), and China (4.7%).[32] Therefore, just two years before the coup, Guinea-Bissau was already doing a substantial amount of business with non-western countries, and I suspect that these numbers have probably shifted even further after the April coup. To illustrate, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Guinea-Bissau first established diplomatic relations on March 15, 1974. These relations were suspended from May 26, 1990 through April 22, 1998 as Guinea-Bissau embraced Western development initiatives and realigned itself with Taiwan. Since 1998, China has vigorously expanded its political, economic, and development initiatives in the country. These include investing in human resources, the construction of a dam on the Ceba River at a cost of $60 million, assistance in building the deep water port in Buba in cooperation with Angola, and the rehabilitation of the country’s highways. China has also built the national parliament building, rehabilitated the presidential palace damaged during the 1998 civil war, constructed an apartment complex for retired military and their families in Bissau, and constructed a six-story central government building. Other assistance includes direct budget contributions to pay civil servant salary arrears as well as privatized banking partnerships between Macau gaming magnate Stanley Ho’s Geocapital, Angolan Banco Privado Atlântico (BPA) and Guinea-Bissau’s Banco da África Ocidental (BAO). In return, China is gaining not only another international ally, but also rights to fish in Guinea-Bissau’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), and opportunities to drill for potential offshore oil reserves.[33] Even after the coup, China has committed $150 million to install wind turbines in the Bijagos archipelago, as well as solar panels in the south of the country to assist with telecommunications.[34]

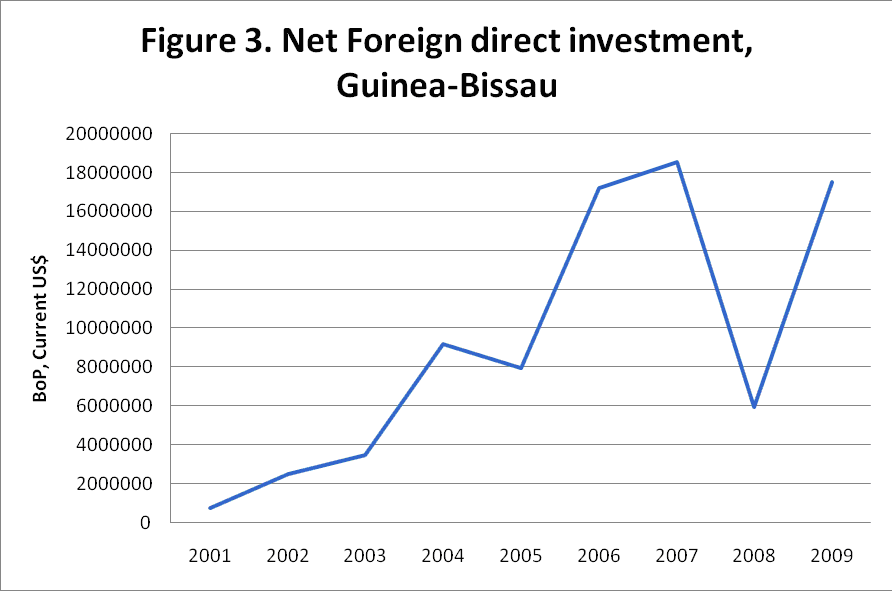

While the 21st century has been a continuation of the missteps of the 20th century so far, the diversification of foreign investment including BRIC nations could help break the cycle. Diverse foreign investment could help usher in the critical element of political stability to allow economic and social institutions to obtain a foothold. Better infrastructure and increased international partners will help alleviate Guinea-Bissau’s susceptibility to the volatility of the cashew market since economic diversification is unlikely. Only time will tell if this spreading of foreign investment into Guinea-Bissau will help it escape the cycle of failed statehood (Fig. 3).[35]

SOURCE:http://data.worldbank.org/country/guinea-bissau, 2012

—

Brandon D. Lundy is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Interim Associate Director of the Ph.D. Program in International Conflict Management at Kennesaw State University. His forthcoming book, Teaching Africa: A Guide to the 21st Century Classroom (Indiana University Press) is scheduled for release in spring 2013.

Image 1. A Chinese storefront in the capital of Bissau, 2011. Photo credit: Brandon D. Lundy

Image 1. A Chinese storefront in the capital of Bissau, 2011. Photo credit: Brandon D. Lundy

Image 2. This Lebanese merchant eventually settled in southern Guinea-Bissau where he took a local wife. He retains his citizenship, while his children are Bissau-Guinean.[i] Photo credit: Brandon D. Lundy

References:

[1] This statement was made during an email exchange about Carlos Cardoso’s analysis of the April 12, 2012 military coup (“Guinea-Bissau: The Real Reason for the Coup d’État”, Pembazuka Press, May 22, 2012, http://pambazuka.org/en/category/features/82234) between Guinea-Bissau scholars including Abel Djassi Amado, Carlos Cardoso, Teresa Almeida Cravo, Rosemary Galli, Toby Green, Peter Karibe Mendy, and Lars Rudebeck.

[2] For example, see Gorjão, Paulo (2010) “Guinea-Bissau: The Inescapable Feeling of Déjà Vu”, IPRIS Policy Brief 2(April):1-8, http://www.ipris.org/?menu=6&page=39; Perdigao, Nayanka (2012) “The challenges in Guinea Bissau: A glass half full”, Consultancy Africa Intelligence, 16 May, http://www.consultancyafrica.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1018:the-challenges-in-guinea-bissau-a-glass-half-full-&catid=60:conflict-terrorism-discussion-papers&Itemid=265; Valentim, Inácio (2009) “Guinea-Bissau: From ashes to uncertainty”, IPRIS Lusophone Countries Bulletin 2(December):4-5, http://www.ipris.org/?menu=6&page=57; Zounmenou, David (2011) “Guinea-Bissau in 2011: Between Stability and Uncertainties” IPRIS Lusophone Countries Bulletin: 2011 Review:21-26, http://www.ipris.org/?menu=6&page=57.

[3] FiS (Fish Information & Services), (2012) “Forty Spanish Vessels no longer fish in Guinea Bissau”, European Union (June 18), http://fis.com/fis/worldnews/worldnews.asp?monthyear=6-2012&day=18&id=53098&l=e&country=&special=&ndb=1&df=1, accessed July 5; IRIN (2012a) “Guinea-Bissau: Falling cashew exports raise hardship”, Bissau, 15 August, http://www.irinnews.org/Report/96106/GUINEA-BISSAU-Falling-cashew-exports-raise-hardship, accessed August 29; Reuters (2012a) “Guinea-Bissau Is Suspended by African Union” The New York Times, World Briefing (Africa), April 17, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/18/world/africa/guinea-bissau-is-suspended-by-african-union.html?_r=0.

[4] See for example, Fistein, David (2011) “Guinea-Bissau: How a Successful Social Revolution Can Become an Obstacle to Subsequent State-Building”, International Journal of African Historical Studies 44(3):443-455; Forrest, Joshua B. (2003). Lineages of State Fragility: Rural Civil Society in Guinea-Bissau. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press; Valentim (2009); Zounmenou (2011).

[5] DAC stands for Development Assistance Committee, which is a forum for selected Organization for Economic Co-operation (OECD) member states to discuss issues surrounding aid, development, and poverty reduction in developing countries. It describes itself as being the “venue and voice” of the world’s major donor countries (http://www.oecd.org/dac/).

[6] The World Bank country data for Guinea-Bissau (2012), http://data.worldbank.org/country/guinea-bissau.

[7] The World Bank country data for Cape Verde (2012), http://data.worldbank.org/country/cape-verde.

[8] Boubacar-Sid, Barry, Edward G. E. Creppy, Estanislao Gacitua-Mario, and Quentin Wodon, eds. (2007) “Conflict, Livelihoods, and Poverty in Guinea-Bissau”, World Bank Working Paper No. 88, Washington, DC: The World Bank; Bordonaro, Lorenzo Ibrahim (2009) “Introduction: Guinea-Bissau Today—The Irrelevance of the State and the Permanence of Change”, African Studies Review 52(2):35-45; Gable, Eric (2009) “Conclusion: Guinea-Bissau Yesterday… and Tomorrow”, African Studies Review 52(2):165-179; Thaler, Kai (2009) “Avoiding the Abyss: Finding a Way Forward in Guinea-Bissau”, Portuguese Journal of International Affairs 2(Autumn/Winter):3-14.

[9] Bloching, Sebastian (2010) “EU SSR Guinea-Bissau: Lessons Identified”, European Security Review 52(Novmeber):1-8; ICG (International Crisis Group) (2012) “Beyond Compromise: Reform Prospects in Guinea-Bissau”, Africa Report No. 183, (January 23), Dakar/Brussels, http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/regions/africa/west-africa/guinea-bissau/183-beyond-compromises-reform-prospects-in-guinea-bissau.aspx.

[10] African Elections Database (2012) “Elections in Guinea-Bissau”, http://africanelections.tripod.com/gw.html, accessed July 16.

[11] See also, Gorjão, Paulo, and Pedro Seabra (2012a) “Guinea-Bissau: Can a Failed Military Coup be Successful?” IPRIS Viewpoints 95(May):1-3, http://www.ipris.org/?menu=6&page=52; ICG (International Crisis Group) (2012) “Beyond Turf Wars: Managing the Post-Coup Transition in Guinea-Bissau”, Africa Report No. 190 (17 August), http://www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/Files/africa/west-africa/guinea-bissau/190-beyond-turf-wars-managing-the-post-coup-transition-in-guinea-bissau, accessed September 11; Posthumus, Bram (2012a) “How will West African Posturing Affect Guinea Bissau?: Anger is mounting over perceived external control in Guinea-Bissau”, Think Africa Press (12 June), http://thinkafricapress.com/guinea-bissau/west-african-shenanigans-around-coup-ecowas-angola-gomes; Reuters (2011) “Heroes to villains: army is Bissau’s big problem”, http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/04/05/bissau-military-reform-idUSL6E8F10EV20120405 , accessed April 5, 2012.

[12] See, A SEMANA (2012) “Military Command blames Angola for last week’s coup”, 17 April, http://asemana.sapo.cv/spip.php?article75206&ak=1 ; BBC News Africa (2012) “Guinea-Bissau: Junta hands back power to civilians”, 23 May, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-18173355; Gorjão, Paulo, and Pedro Seabra (2012b) “Guinea-Bissau: ECOWAS ‘Zero Tolerance’ Principle is Highly Tolerant After All”, Royal African Society, African Arguments, May 9, http://africanarguments.org/2012/05/09/guinea-bissau-ecowas-%e2%80%9czero-tolerance%e2%80%9d-principle-is-highly-tolerant-after-all-by-paulo-gorjao-and-pedro-seabra/; Hatton, Barry (2012) “Guinea-Bissau rambles on, despite coup”, Associated Press, Bissau (May 27), http://bigstory.ap.org/content/guinea-bissau-rambles-despite-coup; Reuters (2012b) “Bissau releases former navy chief held in coup plot”, Reuters Africa, Bissau (June 21), http://af.reuters.com/article/guineaBissauNews/idAFL5E8HLBX020120621, accessed July 10.

[13] Ferreira, Armindo (2012) “As Crises Político-Militares na Guiné-Bissau: Causas, problemas e Soluções”, Journal Expresso das Ilha No. 546 (Especial Guiné-Bissau, 16 May):1-5, http://www.slideshare.net/Cantacunda/as-crises-polticomilitares-na-guinbissau; Herbert, Nelson (2012) MISSANG: Crónica de um Fracas: Os Altos e Baixos de uma Relação Estado a Estado”, Journal Expresso das Ilha No. 546 (Especial Guiné-Bissau, 16 May):6-8, http://www.slideshare.net/Cantacunda/as-crises-polticomilitares-na-guinbissau.

[14] Madeira, Luís Filipe, Stéphane Laurent, and Sílvia Roque (2011) “The international cocaine trade in Guinea-Bissau: current trends and risks”, NOREF (Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre) Working Paper (February), Oslo:1-18, http://www.peacebuilding.no/Regions/Africa/Publications/The-international-cocaine-trade-in-Guinea-Bissau-current-trends-and-risks; Zeidler, Andreas (2011) The State as a Facilitator in the Illicit Global Political Economy: Guinea-Bissau and the Global Cocaine Trade, MA thesis, International Studies at the University of Stellenbosch, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Department of Political Science.

[15] Monteiro, António Isaac, Coordenador (1996) O Programa de Ajustamento Estrutural na Guiné-Bissau: Análise dos efeitos Sócio-Económicos. Bissau: Instituto National de Estudos e Pesquisa (INEP).

[16] Bashir, Misbahu (2012) “Nigeria: Police Deploy 140 Peacekeepers to Guinea-Bissau”, allAfrica.com, 11 June, http://allafrica.com/stories/201206111056.html, accessed July 5.

[17] ICG (2012).

[18] IRIN (2012b) “Analysis: Division and stasis in Guinea-Bissau”, Dakar/Bissau, 18 May, http://www.irinnews.org/Report/95483/Analysis-Division-and-stasis-in-Guinea-Bissau, accessed September 15; Gorjão and Seabra (2012b); Amnesty International (2012) “Guinea-Bissau: Amnesty International’s Concerns Following the Coup in April 2012”, AFR 30/001/2012, http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/info/AFR30/001/2012/en.

[19] The World Bank country data for Guinea-Bissau (2012); UNDP (United Nations Human Development Programme) (2011) “Human Development Report 2011: Sustainability and Equity: A Better Future for All, Guinea-Bissau Country Profile: Human Development Indicators”, http://hdrstats.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/GNB.html, accessed July 17, 2012.

[20] Posthumus, Bram (2012b) “Guinea-Bissau: They Call Guinea Bissau a Narco-State – So What?”, 30 August, http://allafrica.com/stories/201208310855.html, accessed September 11; The World Bank country data for Guinea-Bissau (2012; Transparency International (2012) “Corruption by Country/Territory: Guinea-Bissau”, http://www.transparency.org/country#GNB, accessed September 14.

[21] Fis (2012).

[22] Hindustan Times (2012) “How India ruined an African country”, August 28, http://www.hindustantimes.com/world-news/Africa/How-India-ruined-an-African-country/Article1-920390.aspx, accessed September 11; IRIN (2012c) “Guinea-Bissau: Falling cashew exports raise hardship”, Bissau, 15 August, http://www.irinnews.org/Report/96106/GUINEA-BISSAU-Falling-cashew-exports-raise-hardship, accessed September 11; Lundy, Brandon D. (2012) “Playing the Market: How the cashew “commodityscape” is redefining Guinea-Bissau’s countryside”, Culture, Agriculture, Food and Environment (CAFÉ): The Journal of Culture & Agriculture 34(1):33-51; macauhub (2012a) “Guinea Bissau faces problems distributing cashew nut production”, August 22, http://www.macauhub.com.mo/en/2012/08/22/guinea-bissau-faces-problems-distributing-cashew-nut-production/, accessed September 11; Reuters (2012c) “Guinea Bissau coup set to halve cashew production – UN”, July 26, http://af.reuters.com/article/guineaBissauNews/idAFL2E8IQI5420120726, accessed September 12.

[23] IRIN (2012a)

[24] United States Department of State (1998) “Guinea: U.S. Suspends Embassy Operations in Guinea-Bissau”, June 16, http://allafrica.com/stories/199806160146.html, accessed September 12, 2012.

[25] See Africare – Guinea-Bissau, http://www.africare.org/our-work/where-we-work/guinea-bissau/index.php.

[26] The World Bank country data for Afghanistan (2012), http://data.worldbank.org/country/afghanistan; The World Bank country data for Cape Verde (2012); The World Bank country data for Guinea-Bissau (2012); The World Bank country data for Iraq (2012), http://data.worldbank.org/country/iraq.

[27] Chabal, Patrick (2003) Amilcar Cabral: Revolutionary Leadership and People’s War. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, Pp. 83-89.

[28] Reuters (2012d) “Bissau government to review Angola Bauxite deal, calls it unfair”, August 23, http://af.reuters.com/article/guineaBissauNews/idAFL6E8JNHFM20120823, accessed September 12.

[29] macauhub (2006) “International consortium to mine for phosphates in Guinea Bissau”, September 27, http://www.macauhub.com.mo/en/2006/09/27/1795/, accessed September 11, 2012.

[30] Tehran Times (2012) “Iran signs cooperation deal with Guinea-Bissau”, Tehran, 4 September, http://tehrantimes.com/politics/101221-iran-signs-cooperation-deal-with-guinea-bissau, accessed September 11.

[31] Vietnam News Agency (2012) “Viet Nam plans to import 357,000 tonnes of cashews”, HCM City, August 21, http://vietnamnews.vnagency.com.vn/Economy/229039/viet-nam-plans-to-import-357000-tonnes-of-cashews.html, accessed September 11.

[32] For International Trade Statistics, see the World Trade Organization yearly reports, http://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/its_e.htm .

[33] Chinese Foreign Ministry (2006) “Guinea-Bissau”, October 10, http://www.china.org.cn/english/features/focac/183519.htm; Horta, Loro (2010) “Guinea-Bissau: China Sees a Risk Worth Taking”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, http://csis.org/story/guinea-bissau-china-sees-risk-worth-taking, accessed November 6; macauhub (2007) “Stanley Ho’s Geocapital enters Guinea-Bissau finance sector”, July 23, http://www.macauhub.com.mo/en/2007/07/23/3413/; macauhub (2010a) “Macau to host forum on China’s cooperation with Portuguese language countries in November”, October 19, http://www.macauhub.com.mo/en/2010/10/19/9973/; macauhub (2010b) “Banks from Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde sign cooperation agreement”, October 18, http://www.macauhub.com.mo/en/2010/10/18/9971/; macauhub (2011) “China to finance reconstruction of Guinea-Bissau’s Palace of the Republic”, October 26, http://www.macauhub.com.mo/en/2011/10/26/china-to-finance-reconstruction-of-guinea-bissau%E2%80%99s-palace-of-the-republic/.

[34] Macauhub (2012b) “China to fund installation of wind energy in Guinea Bissau”, August 31, http://www.macauhub.com.mo/en/2012/08/31/china-to-fund-installation-of-wind-energy-in-guinea-bissau/, accessed September 11.

[35] The World Bank country data for Guinea-Bissau (2012).

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Pragmatism over Morals?

- Opinion – The US-China Tech Hegemony Contest: A Threat to the Neoliberal World Order

- Contested Multilateralism as Credible Signalling: Why the AIIB Cooperates with the World Bank

- Opinion – Taiwan Could Be to China What Canada Is to the US

- Opinion – China’s Role in Mediating Middle East Crises

- Why the West Needs to Stop its Moralising against China