Introduction

‘The origin of piracy as a criminal offence, in English law, lies in the 1536 acte for the punysshement of pyrotes and robbers at sea’ (Kavanagh, 1999, pp. 129) From this we can instantly see that Britain has a long history of dealing with piracy and, importantly, viewing pirates as criminals. In this paper I will argue that the UK predominantly views pirates as criminals and that the primary means to eradicate a criminal problem is to arrest and prosecute as many as possible in an effort to change a pirate’s risk/benefit analysis. It is important not to oversimplify this discussion as the UK is not a unitary actor but one with many different opinions, priorities and capabilities. ‘According to the Foreign Secretary: The FCO works closely with the Ministry of Defence, the Department for Transport and the Department for International Development on the issue of Somali piracy’ (HoC[1]: Foreign Affairs Committee, 05/01/2012, pp.42). In addition I will take the Royal Navy as distinct from the Ministry of Defence as it had a rather more focused view.

There are currently three naval coalitions in the Gulf of Aden, and the UK at some point has been involved in all of them. They include the US led Combined Joint Task Force-151, the NATO Operation Ocean Shield and the European Union’s EU NAVFOR Atalanta. The UK has been active in securing prosecutions for pirates building up a number of transfer agreements with countries in the region so that the Royal Navy can pass them over. There has been an effort to work with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) on capacity building in and around Somalia. As a nation with a strong maritime history, it would seem the UK feels it has a vocation to provide a lead in the fight against piracy. This was reaffirmed by the Commons Foreign Affairs Committee who said: ‘As a state whose strengths and vulnerabilities are distinctly maritime, the UK should play a leading role in the international response to piracy.’ (HoC: Foreign Affairs Committee, 05/01/2012, pp3). This explains Britain’s efforts to take a lead in counter piracy. For instance EU NAVFOR Atalanta is the first CSDP mission to be under British command, both NATO and EU missions choosing to base their headquarters at Northwood, and the UK Maritime Trade Operation in Dubai, which operates a 24 hour reporting centre to enable swift communication between merchant shipping and naval forces (FCO[2] Naval Operations, 18/08/2011). As I shall discuss, the British lead is important because it is backed up by a heroic narrative whereby the British Royal Navy are sailing off to defend its citizens against cruel pirates in film like style. The dominant understanding of piracy, however, is centred on criminals and prosecutions which I believe can be tied to the British understanding of how to deal with criminals domestically. I will examine how strong the pull is to more land based activities as well as the idea that there is a war against pirates. It would seem that on a basic level the UK acted on its states perception of the piracy threat, however, the closer you get the more confused policy seems to become.

The UK’s Perception of Piracy

In a speech to the chamber of shipping, FCO minister Henry Bellingham stated ‘the turnover of the British shipping industry is worth £10.7Bn of our national GDP’ in an effort to demonstrate why piracy is important to the UK (Bellingham, 12/10/2011). In examining the UK perception of piracy and its importance, whatever other frames are mentioned, the money problem is behind it. This may explain the main tension between a naval approach and the relentless rhetoric stating ‘we have always been clear that the problem of piracy has got to be solved on land’ (Bellingham, 12/10/2011), ‘It has become a truism that the long-term solution to piracy lies on land in Somalia’ (HoC, Foreign Affairs Committee, 05/01/2012, pp4) and ‘…whilst the root causes of piracy lie on land so does the solution.’ (Hague, 23/02/2012). It is stated that for piracy to occur you require economic dislocation from rapid development, recognition of piracy as an available cultural possibility and the opportunity to carry out piracy (Vagg, 1995, pp. 63). In line with this the UK appears to focus specifically on the final factor through naval forces patrolling the Indian Ocean and Gulf of Aden. A second set of conditions that are required for piracy have been identified focusing specifically at the Somali example. They are: the existence of a favourable environment, the prevalence of ungoverned spaces, the existence of weak law enforcement, and the availability of great rewards for piracy while the risks are minimal (Samatar et al, 2010, pp. 1378). The government appears most conscious of the high rewards on offer and seeks to ‘change the perceived risk/reward ratio for pirate activity’ (HoL[3], European Union Committee, 2010, pp. 6). In addition to changing the risk/reward ratio, it is stated that ‘the government is clear that pirates must pay for their actions’ (Bellingham, 2011). This indicates that there is something more than simply making sure that UK trade does not suffer, with the inclusion of justice and moral standards. The UK government could be accused of oversimplifying the issues by creating a ‘bad guy’ image for the pirates, which I will return to with regards to the Royal Navy.

I have mentioned that I take the UK’s dominant perception to be one of a criminal problem but it is useful to be aware of the varying views with the UK as an actor. The Ministry of Defence has set out seven military tasks, three of which demonstrate a commitment to counter piracy. They are a commitment to ‘supporting the civil emergency organisations in times of crisis’, ‘defending our interests by projecting power strategically and through expeditionary operations’, and finally ‘providing security for stabilisation’ (MOD[4] The Strategy for Defence, 2011, pp. 3). All three of these areas can encompass piracy showing it as recognised within military tasks. The second task mentioned links to the idea that ‘the political need to fight piracy has presented a political opportunity for nations to increasing their naval presence in the region to serve other national purposes’ (Willett, 2012, pp.20). Linked to the statement ‘you don’t need to be a big navy to make a difference’ (Willett, 2012, pp.22) it is easy to see why this is a strategically attractive option for the British Royal Navy who, while not being small, is challenged by cuts and opposing operational demands.

While not in the headlines, The Department for Transport (DfT) is involved in everyday counter piracy measures. The DfT view piracy as a security, and a health and safety issue. This can be seen by their ‘Guidance to UK Flagged shipping on Measures to counter Piracy, Armed Robbery and other acts of violence against merchant shipping’ (DfT[5], 2011). The DfT focus far less on the pirates and their activities but instead provide information to assist ‘all UK registered ship owners, companies, ship operators, masters and crews’ (DfT, 2011, pp. 5).

The Department for International Development is the department charged with coming up with a ‘solution on land’. The DFID[6] demonstrates a more humanitarian perception of piracy focussing less on the crimes committed and changing the debate to look at piracy as a symptom of larger problems. They argue that ‘unemployment and extreme poverty….play a key part in young men turning to piracy…’ (DFID world must address failure…, 2012). Although only partly involved in counter piracy activities I will come back to the DFID when looking at activities as there is a possibility the UK may recently be moving further to this position.

I mentioned the idea that the government is simplifying the issues of piracy where pirates are ‘bad guys’ and the Royal Navy are playing the part of the valiant police. I argue that the Royal Navy is developing a heroic narrative and this is displayed in various ways. One recent news article simply finished with “the Crews final comment was: please help.” “And that is what we went in to do” (Royal Navy ‘overwhelming show of force…, 2011). Language of ‘pirate-busting’ (Royal Navy the Knight rides…, 2011) and ‘efforts to strangle the piracy scourge’ (Royal Navy naval force returns…, 2012). These news reports published by the Royal Navy all point to the view that the UK think of themselves as the ‘good guys’ saving poor fishermen and guarding the World Food Programme. The War in Afghanistan, dragging on for over ten years with virtually no positive press may give the Royal Navy an incentive to parade its counter piracy activities as wins. The narrative also provides cover for the more traditional power based reasons for being in the region. But the main issue to note with the heroic narrative is the idea that the Navy will sail in and arrest the ‘bad guy’ fixing the piracy problem forgetting that the solution lies on land as the government has stated.

In an essay directed at the European Union (EU) several reasons have been laid out for why the EU is concerned with piracy, and although not intended, I contend that the list fits the UK as well as its order being quite telling. They are firstly that piracy constitutes a threat to EU citizens, secondly that pirate raids harm maritime trade, next piracy in the horn of Africa constitutes a threat to energy security, fourth is the possibility that pirates would form a link with terrorist groups, fifth is the concern that piracy constitutes a risk to marine environment and lastly, both in this list and in importance, I would argue is that piracy harms Somalia (Germond and Smith, 2009, pp. 580). Now that we have discussed some of the various perceptions the UK holds on piracy and reason for why the UK is interested in piracy I will move on to the UK’s counter piracy activities.

The UK’s Counter Piracy Activities

To examine the UK’s counter piracy activities I have divided the discussion by looking separately at the Department for Transport based initiatives, Naval Based activities, initiatives directed at the prosecution of pirates and finally any land based activities. Although there is inevitably going to be some overlap, there will be merit in identifying which of these areas are favoured before I move on to examine if there are any inconsistencies between perceptions of piracy and activities.

Transport Based

The DfT has developed ‘guidance to UK flagged shipping on measures to counter piracy, armed robbery and other acts of violence against merchant shipping’ in 2011. This includes some basic information on ‘the importance of taking action to deter such acts and advises on how to deal with them should they occur’ (DfT guidance to…., 2011, pp 5). The DfT also play a quasi-regulatory role with regard to armed guards stating ‘shipping companies that decide to use armed guards…must refer and adhere to the government’s interim guidance to UK flagged shipping on the use of armed guards…’ (DfT guidance to…., 2011, pp. 34). The DfT is responsible for the ‘United Kingdom National Maritime Security Programme’ ‘to provide a comprehensive protective security regime for UK ships and ports’ (DfT brief overview of…, 2008). The DfT regulates the International Ship and Port Facility Security (ISPS) code which was created post 9/11. The National Maritime Security Committee is used for consultation with the maritime industry (DfT brief overview of…, 2008). The DfT contributes with other departments to contingency plans and responses to maritime security alerts and incidents (DfT brief overview of…, 2008). From these measures we can see that the DfT have a low key but very important role in regulating and advising maritime security for UK shipping.

Naval Based

There are currently three multinational task forces to counter piracy in the Gulf of Aden and off the coast of Somalia. The Royal Navy states that their ‘purpose is to deter, disrupt and suppress piracy and protect ships going about their lawful business, securing freedom of the seas for all nations.’ (Royal Navy, Counter Piracy) In addition to the multinational task forces, national navies also act unilaterally. To coordinate these efforts in 2008 the Shared Awareness and Deconfliction (SHADE) mechanism was established to improve coordination and minimise duplication (Hoc, Foreign Affairs Committee, 2012, pp. 29). Further to this, UN resolution 1851 called for the establishment of the UN Contact Group on Piracy off the Coast of Somalia (CGPCS). The contact group has five working groups and the UK chairs Working Group 1. Working Group 1 works ‘improving naval operational co-ordination and building the judicial, penal and maritime capacity of regional states to ensure they are better equipped to tackle piracy’ (FCO, International Response, 18/08/2011)

The European Union’s EUNAVFOR Operation Atalanta is the first ever EU Naval operation. Its original mandate was for one year from December 2008, but was extended in 2009 and 2010 to 2012 and looks likely to be extended further (Hoc, Foreign Affairs Committee, 2012, pp. 28). EUNAVFOR Atalanta’s main tasks are to escort merchant shipping vessels carrying aid for the World Food Programme as well as vessels of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), protect vulnerable shipping in the Gulf of Aden and Indian Ocean, and lastly to monitor fishing activity off the coast of Somalia. (EUNAVFOR Somalia, 31/01/2011). Member states can contribute to the operation in a number of ways including navy vessels, maritime patrol and reconnaissance aircrafts, Vessels Protection Detachment teams as well as providing staff for the headquarters. The force usually consists of four to seven surface combat vessels and one to two auxiliary ships. (EUNAVFOR Somalia, mission, pp. 2). The Mission claims to be utilising a comprehensive approach with an EU Training Mission in Uganda, support to AMISOM, giving Development aid from the EDF and Humanitarian aid from ECHO. (EUNAVFOR Somalia, mission, 31/01/2011). This approach has, however, been criticised as not comprehensive with ‘a piecemeal approach…still prevalent’ and secondly that the EU has placed too much emphasis on military means with the dangers that come with becoming embroiled in a civil conflict (Petretto and Ehrhart, 22/03/2012). These criticisms are important as they are echoed in the UK approach which has a challenge to coordinate all the different departments and may be guilty of prioritising military means. The British have had some reservations about CSDP missions in general and were lukewarm to Atalanta. NATO, however, was becoming overstretched in Afghanistan and thus ‘it was still preferable to doing nothing or- even worse- allowing the French to take the lead in a high-profile multinational anti-piracy operation that clearly affected British shipping interests.’ (Petretto and Ehrhart, 22/03/2012). Once agreed the UK’s role was enhanced when it was decided that the operation would be commanded by a British rear admiral and that the headquarters would be located at Northwood in the UK (Petretto and Ehrhart, 22/03/2012).

NATO launched Operation Ocean Shield in August 2009 and succeeded two shorted counter piracy operations, Operation Allied Provider from October to December 2008 and Operation Allied Protector from March to August 2009 (NATO, Counter-piracy operations, 09/02/2012). Its main focus is counter piracy activities at sea but also contributes to capacity building efforts for regional states wishing to act against piracy (HoC, Foreign Affairs Committee, 2012, pp. 28). This winter NATO has had a ‘surge’ against piracy with the Royal Navy having disrupted the actions of seven pirate groups, freeing 43 sailors held hostage and handing over 36 suspects for prosecution. (Royal Navy, Navy’s surge…, 15/02/2012)

The third operation in counter piracy is the Combined Joint Task Force 151 (CTF-151) launched in January 2009 as a US led multinational force. (Hoc, Foreign Affairs Committee, 2012, pp. 28) The CTF-151 works ‘actively to deter, disrupt and suppress piracy’. The Royal Navy acting under NATO, in conjunction with the CTF-151 launched a mission to rescue hostages held on the Italian ship the MV Montecristo on 11th October. With the crew taking safety in the citadel, the Royal Navy launched a Lynx to hover overhead with snipers while Royal Marines proceeded to board the ship before the pirates surrendered (Townsley, The MV Montecristo…..). This is important as it shows a growing willingness to use force to arrest pirates and free hostages. Further to the liberation of the hostages, later in the same week the HMS Somerset acting under the CTF-151 stopped a suspected pirate mothership thought to have been used to launch the attack on the MV Montecristo whilst also freeing 20 Pakistani fishermen (Royal Navy, Navy strikes third.., 20/10/2011). This would signal growing success in the naval operations which corresponds with the fact that while the number of attacks in 2010 remained consistent with the previous year, the number of attacks that had been prevented went up by 70% (HoL, European Union Committee, 14/04/2010, pp. 14). This kind of hostage rescue operation was explicitly advocated by the Chandlers who were kidnapped on 23rd October 2009 with the Royal Navy acting more cautiously than in the case of the Montecristo (HoC: Foreign Affairs Committee, 05/01/2012, pp17). There are worries however that this signals an escalation in the violence involved with piracy. This was demonstrated recently when a Danish warship open fired on a pirate mothership to prevent it from fleeing. There were 18 hostages on the boat and two of them died (Los Angeles times, 28/02/2012). The use of force seems to be a constant tension within the UK with some arguing for more interventions but the Foreign Affairs Committee concluded ‘the cautious approach to military operations when hostages are involved is appropriate and agree that protecting the safety of hostages is paramount. However, if the use of violence against hostages continues to increase this may change the balance of risk in favour of military intervention in the future.’ (HoC: Foreign Affairs Committee, 05/01/2012, pp34). This statement gives us a clear willingness to increase the use of force if the treatment of hostages changes.

Prosecution Based

In the communiqué from the London Conference on Somalia it was stated that ‘there will be no impunity for piracy. We called for greater development of judicial capacity to prosecute and detain those behind piracy.’ (FCO, London conference on Somalia, 23/02/2012). The international law on piracy is laid out in articles 100 to 107 of the UN Convention on the Laws of the Sea (UNCLOS). Article 105 states ‘On the high seas, or in any place outside the jurisdiction of any State, every State may seize a pirate ship or aircraft, or a ship or aircraft taken by piracy and under the control of pirates, and arrest the persons and seize the property on board’. (Treves, 2009, pp. 401-402) This has been extended by Security Council resolutions to permit counter piracy actions within Somali waters.

The UNODC[7] counter piracy programme has been in place since May 2011, with two related aims. Firstly, to support regional piracy prosecutions and secondly, to support additional prison capacity in Somalia through the piracy prisoner transfer programme (UNODC, Counter Piracy Programme…, 2011, pp. 1). The UK has confirmed that it will make a further donation this year to the UNODC of £2 ¼ million to support work in Mauritius, the Seychelles, Tanzania and Somalia (Bellingham, 2011).

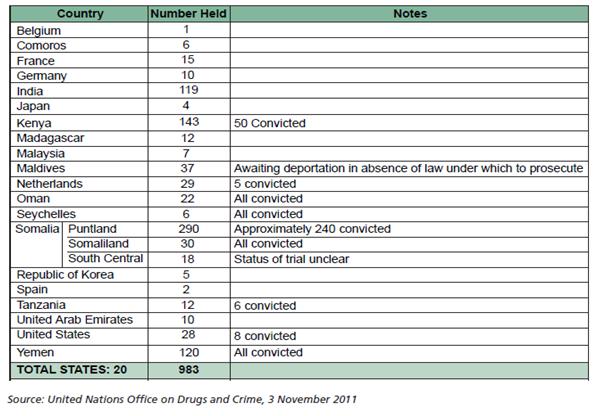

Unlike land based efforts which we will see are largely based around donations with regard to prosecutions the UK has made some unilateral efforts. The UK signed a MOU[8] with Kenya for the transfer of pirates for prosecution in December 2008 and another with the Seychelles in July 2009 (FCO, prisoner transfers, 16/08/2011). An example of this was demonstrated recently when the RFA Victoria arrested 14 pirates on a hijacked dhow before handing them over to the Seychelles for prosecution (Royal Navy, pirates face justice…2012). Further to this, at the London conference on Somalia it was announced that a MOU with Tanzania had been signed and an agreement with Mauritius would follow later this year (FCO, Somalia conference sees important…, 23/02/2012). With prison capacity work continuing, in a new move the UK has also pushed for post-sentence transfers back to Somalia with Somaliland signing an agreement with the Seychelles and Puntland showing interest. The Foreign Affairs Committee, as well as the HoL European Union Committee, have criticised the government for failing to track ransom money and letting ‘kingpins’ get away, with the Minister admitting ‘it is fair to say that we were possibly slow to look at this area as a priority’ (HoC, Foreign Affairs Committee, 2012, pp. 59). This looks set to change with William Hague announcing ‘the UK is to provide the director and fund the construction of the new Regional Anti-Piracy Prosecutions Intelligence Co-ordination Centre (RAPPIC) based in the Seychelles’ (FCO, International Community Targets Kingpins, 21/02/2012). The RAPPIC will be used to turn intelligence into useable evidence which has been a big problem for the Navy with hostages being unwilling to testify, the need to catch pirates in the act and the general difficulty in telling the difference between pirates and fishermen (HoC, Foreign Affairs Committee, 2012, pp. 45). From these new measures we can see a substantial shift away from disrupting pirate activities to prosecuting pirates. The UK appears to be taking a lead in finding new and novel ways to tackle the issues that arise when attempting to prosecute pirates. However, the Kenyan agreement has run in to difficulties with the Kenyan government who are ‘unhappy with the lack of support provided for prosecuting and holding pirates’ (Hoc Foreign Affairs Committee, 2012, pp. 51) It may also be asked if the Naval operations, coupled together with the huge diplomatic effort involved in constructing these agreements, are worth it when you look at the number of pirates detained. The table below shows firstly the low number held but also the fact that a number of other states have prosecuted pirates domestically, while the UK has refused so far to do so.

Land Based

‘In 2010, the UK Government set up the British Office for Somalia, based out of the British High Commission in Nairobi,’ and on 2nd February 2012 the British announced its first ambassador to Somalia for 21 years, with an embassy opening when possible (FCO, UK Diplomatic Relations…, 02/02/2012). The UK supports the establishment of the UN Political Office for Somalia in an effort to engage with the local politics. Further to this the UK supports AMISOM with approximately £27.3 million over this financial year (HoC: Foreign Affairs Committee, 05/01/2012, pp 63). In March 2011 the DFID announced it was to increase its aid to Somalia to £63 million per year while the FCO has provided over £6 million in the last year to support counter piracy capacity building programmes. (HoC: Foreign Affairs Committee, 05/01/2012, pp3). In October 2011 Henry Bellingham announced that the government was to commit £2 million to ‘community engagement and economic development in coastal regions’. (Bellingham, 2011) Interestingly, Bellingham also stated that the government was working with industry to attempt to bring them in to the fold with regard to land based development (Bellingham, 2011). Although this sounds like quite a progressive policy, so far it is just a good idea and nothing more. But under the DFID there are some more concrete plans to tackle the causes of piracy. The DFID states that ‘aid projects focused on resolving local conflict and strengthening the police are expected to double next year’, as well as, stating that ‘job creation and economic development will also double, creating 45,000 jobs across Somalia by 2015.’ (DFID, World must address…, 30/01/2012) This has a clearer focus and was announced shortly before the London Conference on Somalia held on 23rd February 2012. On the 22nd of February 2012 Andrew Mitchell, the International Development Secretary, announced the creation of the International Stability Fund to be led by Britain to ‘help create jobs, agree local peace deals and set up police, courts and basic services in areas where there is less fighting’ (DFID, UK leads efforts… 22/02/2012). These recent developments could be seen as a trend towards a more land based approach. However it is far too early to tell if they are purely rhetorical or a genuine change.

Consistencies Between Perceptions and Activities

I noted before that the UK’s main perception of piracy appears to be of a criminal problem that requires prosecutions. Following this frame, it would appear that the UK is acting relatively consistently. Although arguably low numbers have been prosecuted, the UK has made an effort to establish procedures for the effective prosecution and detention of pirates. The FCO has stated that it is ‘working to ensure pirates can be detained and prosecuted, that the proceeds from piracy are pursued and stopped, and that the shipping industry is able to conduct its business as safely as possible.’ (FCO, Piracy, 2011). The recent establishment of the RAPPIC display the government fulfilling its stated commitment ransom payments. The Royal Navy’s recent assertiveness in dealing with pirates also shows the UK’s willingness to act against pirates for prosecutions. But as I stated the number detained have been low and this may point to the main disadvantage of the UK’s approach. The UK is pursuing a policing approach with the Navy arresting pirates in the act and organising transfer agreements and capacity building projects to ensure pirates are brought to justice. This ‘tough on crime’ approach can be linked to a traditional British approach to crime in the UK. New labour claimed to change British policy to a policy of ‘tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime’ (Labour Party, 1997, pp.348) but whether this was achieved in the UK it is not for discussion here. What is clear is that with regard to piracy the UK are tough on crime in the Indian Ocean but failing to be tough on the causes of crime in Somalia. The main problem with this approach of being ‘tough on crime’ is that after pushing pirate activities out of the Gulf of Aden and into the wider Indian Ocean it is near impossible to police. In 2011 I could have finished this evaluation here with a damning verdict on the UK’s ‘tough on crime’ approach. Yet in 2012 there does seem to be a change of tactic with hostage rescue missions (tougher on crime if you will) and a higher engagement with Somalia itself with visits from William Hague to promises of donations for important programmes. It is much too early to tell if these are simply grand statements made for the benefit of the London conference on Somalia but definitely progression to watch.

Conclusion

In this essay while examining the UK’s role in counter piracy it has been important to note the differing perspectives and actions of actors that come under the umbrella of the UK. However, I have stated that the UK’s dominant perspective is of a law enforcement role which has been carried out more and more effectively building up transfer agreements, supporting capacity building projects and the recent establishment of the RAPPIC show real intent on this front. My second conclusion is that while the UK is acting consistently with its main perspective on piracy, it has so far failed with regard to a land based solution. I noted that there have been recent developments and promises by the government, noteably the inclusion of British industry on land. The effectiveness of these measures will have to be the subject of a further essay when these policies can be scrutinised more fully. I noted some criticism of the European Union’s comprehensive approach with an emphasis on military means and a piecemeal approach when it came to land based activities (Petretto and Ehrhart, 22/03/2012). If the UK is viewed, as I believe it should be, not as a unitary actor but as a group of opposing actors then this criticism can be said of the UK as well. The main issue is whether the London Conference on Somalia is a signal towards a more coherent, comprehensive approach or further hollow rhetoric of a land based solution.

Bibliography

Bellingham. H, 12/10/2011, Tackling piracy: UK Government response, http://www.fco.gov.uk/en/news/latest-news/?view=Speech&id=668575182 (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Department for International Development, 22/02/2012, UK leads efforts to bring stability to Somalia, available at http://www.dfid.gov.uk/News/Latest-news/2012/UK-leads-efforts-to-bring-stability-to-Somalia/ , (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Department for International Development, 30/01/2012, World must address failure in Somalia, available at http://www.dfid.gov.uk/News/Latest-news/2012/World-must-address-failure-in-Somalia/ , (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Department for Transport, November 2011, Guidance to UK Flagged Shipping on Measures to Counter Piracy, Armed Robbery and Other Acts of Violence Against Merchant Shipping. Available at http://assets.dft.gov.uk/publications/measures-to-counter-piracy/measures-to-counter-piracy.pdf, (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Department for Transport,14/05/2008, Brief overview of the United Kingdom National Maritime Security Programme, publication type: report, available at http://www.dft.gov.uk/publications/uk-national-maritime-security-programme/ , (accessed, 31/03/2012)

EU NAVFOR Somalia, (no date cited), Mission, http://www.eunavfor.eu/about-us/mission/ , (accessed, 31/03/2012)

EU NAVFOR Somalia, 31/01/2011, EU NAVFOR welcomes the Royal Navy Frigate HMS RICHMOND , published in News by EU NAVFOR Public Affairs Office, http://www.eunavfor.eu/2011/01/eu-navfor-welcomes-the-royal-navyfrigate-hms-richmond/ (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Foreign and Commonwealth Office, 02/02/2012, UK Diplomatic Relations with the Republic of Somalia, http://ukinsomalia.fco.gov.uk/en/about-us/working-with-somalia/uk-diplomatic-relations, (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Foreign and Commonwealth Office, 16/08/2011, Prisoner Transfer Agreements, http://www.fco.gov.uk/en/global-issues/piracy/prisoners , (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Foreign and Commonwealth Office, 18/08/2011, Naval Operations, http://www.fco.gov.uk/en/global-issues/piracy/naval-operations, (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Foreign and Commonwealth Office, 18/08/2011, The International Response to Piracy http://www.fco.gov.uk/en/global-issues/piracy/international-response , (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Foreign and Commonwealth Office, 2011, piracy, http://www.fco.gov.uk/en/global-issues/piracy/ , (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Foreign and Commonwealth Office, 21/02/2012, International Community Targets Pirate Kingpins, http://www.fco.gov.uk/en/news/latestnews/?view=News&id=73304882 , (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Foreign and Commonwealth Office, 23/02/2012, London Conference on Somalia: Communique,http://www.fco.gov.uk/en/news/latestnews/?id=727627582&view=PressS (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Foreign and Commonwealth Office, 23/02/2012, Somali conference sees important new action on piracy, http://www.fco.gov.uk/en/news/latestnews/?view=News&id=734552282 , (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Germond, B, and Smith, M. 2009. Re-Thinking European Security Interests and the ESDP: Explaining the EU’s Anti-Piracy Operation. Contemporary Security Policy 30 (3): 573-593.

Hague. W, 23/02/2012, Foreign Secretary speech ahead of the London Conference on Somalia, http://www.fco.gov.uk/en/news/latestnews/?view=Speech&id=733712482 , (accessed, 31/03/2012)

House of Commons: Foreign Affairs Committee, 05/01/2012, Piracy off the coast of Somalia, London: The Stationery Office Limited, HC 1318

House of Lords: European Union Committee, 14/04/2010 Combating Somali Piracy: the EU’s Naval Operation Atalanta: Report with Evidence, London: The Stationery Office Limited, HL Paper 103

Kavanagh, John, (1999) Law of Contemporary Sea Piracy, The Australian International Law journal.

Labour Party, 1997, Labour Part general election manifesto 1997: new Labour: because Britain deserves better in Dale. I (ed), 1999, Labour Party General election Manifestos, 1900-1997, Routeledge, Oxford

Los Angeles times, February 28, 2012, Two hostages killed as Danish warship fires on Somali pirates available at http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/world_now/2012/02/two-hostages-killed-as-danish-warship-opens-fire-on-somali-pirate-boat.html (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Ministry of Defence, October 2011 The Strategy for Defence, Published by the Ministry of Defence UK available at http://www.mod.uk/NR/rdonlyres/0A42D98D-99B0-4939-863598E172EBCADC/0/stategy_for_defence_oct2011.pdf (accessed, 31/03/2012)

NATO, 09/02/2012, Counter-piracy operations, http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/topics_48815.htm , (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Petretto, K. and Ehrhart, H. 22/03/2012, The EU and Somalia – Counter-Piracy and the Question of a Comprehensive Approach, http://piracy-studies.org/2012/the-eu-and-somalia-counter-piracy-andthe-question-of-a-comprehensive-approach/ , (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Royal navy, (no date given), Counter Piracy , available at http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/Operations/Maritime-Security/Counter-Piracy (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Royal Navy, 13/10/2011 Navy’s “Overwhelming show of force” led to pirate take-down , http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/News-and-Events/LatestNews/2011/October/13/111013-Fort-Victoria-pirate-northwood (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Royal navy, 15/02/2012, Navy’s surge against piracy scourge ends after making ‘a real impact’ available at http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/News-and-Events/Latest-News/2012/February/15/120215-GF-Fort-Vic-Piracy (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Royal navy, 20/01/2012, Naval force returns hijacked dhow to its owner, available at http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/News-and-Events/Latest-News/2012/January/20/120120-Dhow-Return (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Royal navy, 23/12/2011, The Knight Rides Alongside The Fort , available at http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/News-and-Events/Latest-News/2011/December/23/111223-Knight-and-Fort-Vic (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Royal navy, 31/01/2012, Pirates captured by Navy to face justice in Seychelles, available at http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/News-and-Events/Latest-News/2012/January/31/120131-Pirates-Face-Justice (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Royal navy, Navy strikes third major blow in a week against pirates. 20/10/2011, available at http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/News-and-Events/Latest-News/2011/October/20/111020-Third-Major-Blow (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Samatar, Abdi Ismail, Mark Lindberg, and Basil Mahayni. 2010. The Dialectics of Piracy in Somalia: the rich versus the poor. Third World Quarterly 31 (8): 1377-1394.

Townsley. S, (no Date given), The MV Montecristo operation – a promising step in the right direction? RUSI.org, available at http://www.rusi.org/analysis/commentary/ref:C4EB157D0AC0B6/, (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Treves, T. 2009. Piracy, Law of the Sea, and Use of Force: Developments off the Coast of Somalia. European Journal of International Law 20 (2): 399-414.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Counter-Piracy Programme: Support to the Trial and Related Treatment of Piracy Suspects, Issue Seven: September/October 2011, Printing: UNON, Publishing Services Section, Nairobi, available at http://www.unodc.org/easternafrica/en/piracy/index.html , (accessed, 31/03/2012)

Vagg, J. 1995. Rough Seas? Contemporary Piracy in South East Asia. British Journal of Criminology 35 (1): 63-80.

Willett, L. 2012. Pirates and Power Politics. Naval Presense and Grand Strategy in the Horn of Africa. RUSI Journal 156 (6): 20-25.

[1] House of Commons

[2] Foreign and commonwealth Office

[3] House of Lords

[4] Ministry of Defence

[5] Department for Transport

[6] Department for International Development

[7] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

[8] Memorandum of Understanding

—

Written by: Jack Hansen

Written at: Cardiff University

Written for: Dr Christian Bueger

Date Written: April 2012

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Piracy in the Southern Gulf of Mexico: Upcoming Piracy Cluster or Outlier?

- The Future Challenges Facing Europe as a Global Actor

- EU Migration Policy: The EU as a Questionable Actor and a Realist Power

- Human Rights Law as a Control on the Exercise of Power in the UK

- Queer Asylum Seekers as a Threat to the State: An Analysis of UK Border Controls

- US Counter-Terrorism and Right-Wing Fundamentalism