Tim Bale wrote of the “etiology of an obsession”. Tony Blair called it a “virus” and said that “the right have got it bad”. Euroscepticism is a disease and, on this analogy, it could kill the Conservative Party. Bale extended the metaphor by describing the Commons rebellions against the Maastricht Treaty in 1992-93 as the “gateway drug” to the Tories’ addiction to the hard stuff of wanting to leave the European Union altogether.

It is a lovely line, and it certainly captures something of the way that Conservatives find themselves divided on Europe – again – despite themselves. But I do not think that it is accurate or fair to imply that the party is in the grip of an irrational impulse.

It may look as if the Tory party is moving rapidly towards more extreme Euroscepticism. In the later years of John Major’s government, he had to plead with his MPs not to rule out the UK’s ever adopting the euro. The definition of a Eurosceptic then was someone who said that they would never agree to joining the eurozone. As the 1997 election approached, it became more and more difficult to maintain collective ministerial responsibility, and to prevent members of the government putting absolute opposition to the euro in their election addresses.

Compare that with the situation now, when one Tory Cabinet minister – Michael Gove – had his private comments that Britain should leave the EU if it cannot change to a purely trading relationship splashed on the front page of the Mail on Sunday. There was no response from the Prime Minister, and no “clarification” from Gove. From enforcing party discipline on policy towards a proposal unlikely ever to be made, the Tories have given up enforcing discipline on the much more fundamental question of the UK’s membership of the EU. Eurosceptic today refers to those people, who used to be a tiny minority, who say that Britain would be “Better Off Out”.

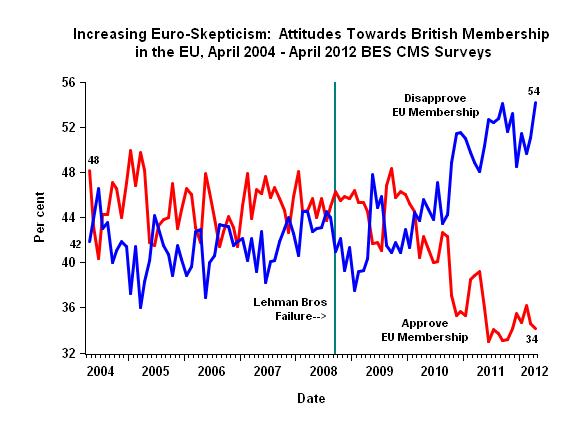

This intensification of hostility towards EU integration has taken place, however, not in some isolated experimentation tank, but in response to changes in Europe. Look at what has happened to British public opinion since the euro crisis became serious – coincidentally at the moment the coalition government was formed in this country.

Source: The British Election Study at the University of Essex

This may not be a particularly considered response. Much of it is probably no more sophisticated than the feeling that the euro has turned out to be a bad idea, an added layer of complication on a deep recession, and something with which we should have nothing to do.

But it is not definitely a wrong response. If the euro survives, it will only be because Germany has managed to create a political union of the eurozone, a union that would have a single budget policy. That is something that the UK would not be part of for the foreseeable future, and it is hard to imagine that the British people would want to be part of it for quite a lot of the unforeseeable future either. The question of what the EU is and what the UK’s relation to it and to its single market is, therefore, a good one to ask, even if it is too early to know how it should be answered.

Indeed, even Blair, who last week repeated his belief in the UK’s European “destiny”, warned against dismissing the Eurosceptic case out of hand. He could imagine Britain outside the EU: “We could create an economy that could operate effectively in the global market,” he said, but we should not want to.

He made the one really persuasive case for staying in the EU and therefore in the single market: that we could not be guaranteed access to it if we left.

“I am very dubious that other European countries would allow Britain to operate like some offshore centre at the edge of Europe, free from Europe’s responsibilities but participating fully in its opportunities. Any one of those countries within Europe could say no – or non – and no would therefore be the likely answer. We want to think long and hard before we put ourselves in that position”.

That is true for now, I think. But who is to say, if there is an enhanced core union of the EU in five years time that the interests of the countries in the outer ring would not be rather different?

It could be said, therefore, that the Conservative Party is not falling victim to a form of madness, but that it is adjusting its proper scepticism about the EU to the challenges of the future. It could be that it is not mad, merely ahead of its time.

—

John Rentoul is chief political commentator for The Independent on Sunday @JohnRentoul

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- We Unhappy Few: The Conservative Party Leadership Race

- Brexit and the 2019 European Elections

- ‘A Union that Strives for More’: Von der Leyen’s All-inclusive EU Narrative

- Influential but Indifferent? Assessing the Role of the Public in European Politics

- The ‘European (Union) Identity’: An Overview

- The British Labour Party after Brexit