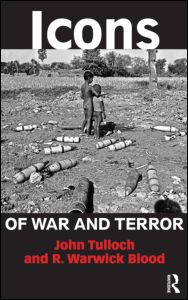

Icons of War and Terror: Media Images in an Age of International Risk

By: John Tulloch and R. Warwick Blood

Routledge, 2012

John Tulloch and Warwick Blood make an interesting team for this study. Tulloch, who has had a significant interest in the cultural politics of the body, was himself the victim of the London bombings of 2005. Tulloch was seriously injured when suicide bomber, Mohammed Sidique Khan, detonated his explosives in an adjacent seat on the London tube.

John Tulloch and Warwick Blood make an interesting team for this study. Tulloch, who has had a significant interest in the cultural politics of the body, was himself the victim of the London bombings of 2005. Tulloch was seriously injured when suicide bomber, Mohammed Sidique Khan, detonated his explosives in an adjacent seat on the London tube.

Seriously injured, Tulloch was visited in hospital by Prince Charles; vision of the injuries and the regal visit became iconic images of the bombings. Through his recovery, Tulloch also became something of a cause celebre, challenging the ideological orthodoxies by which the London bombings have been discussed and explained.

Paradoxically, at the time of the London attacks Tulloch had been working on various studies associated with violence, terrorism and risk. It is perhaps this condition of risk that laid the foundations for this new study, and for his collaboration with Warwick Blood. Blood’s own work on risk, media and human health also represents a significant contribution to the cultural politics of the body. Working with people like Simon Chapman, who has been a thorn in the side of tobacco companies, Blood has been highly critical of the media’s role in promoting risk behaviours that imperil human health.

Whatever the basis of the collaboration, it works very well. The mediated imagery of Tulloch’s own injuries is used as an early example in the book of war iconography. Along with the (in)famous imagery of Neda Soltan’s assassination during the political dissent in Iran in 2009, images of the author’s injuries introduce many of the book’s themes and critical concepts.

In essence, the book examines the ways in which the media construct iconic images of lethal violence, particularly within the context of American global hegemony. While drawing examples from Australia and the United Kingdom, Icons of War and Terror seems especially interested in the colonial project and the ways in which ‘the west’ imposes its interests over developing countries and cultures. In keeping with the authors’ previous studies, this book focuses on the ways in which cultural politics are mobilized by media in the service of particular ideological interests. The authors introduce their book with the death image of Neda Soltan because it:

clearly illustrates how the media are active in constructing icons. In particular, the editorial from Rupert Murdoch’s Australian shows how the making and reporting of ‘a martyr’ is embedded in icon history …These new ‘icons’ and ‘martyrs’ are described in the same terms, ‘battling for democracy’, which the Murdoch press similarly trumpeted in relation to the (old and publicly discredited) Iraq War. (p.5)

The propagation of these icons and martyrs, therefore, isn’t politically neutral but functions within a neo-liberalist ideological framework. Like other notable critics of the corporate media, Tulloch and Blood see the media as both servant and progenitor of these ‘iconic’ systems and the powerful social, economic and military elites that give them force. While the authors generally resist the use of loaded terms like ‘ideology’, there work is clearly critical: the notion of an ‘icon’ seems to have its own political and critical force.

To this end, the propagation of war icons by the media serves the interests of institutional power, including the power of the corporate media itself. The Neda Soltan imagery is delivered across the planet through a media system that is itself socially (and ideologically) ‘iconic’, at least inasmuch as the media are the significant’ conduit of ‘significant’ knowledge about the world. As Tulloch and Blood go on to explore in Icons of War and Terror, this knowledge is fundamentally bound to the promotion of democratic and liberalist values.

There is much to admire in this book. It covers a range of wars that have taken place over the past few decades—Bangladesh, Kosovo, 9/11 and the the Gulf Wars. As noted, the book focuses specifically on the ways in which the corporate media have colluded with ‘western’ political and economic interests to foster a particular conception of global geo-politics and western security needs.

The book recognizes the importance of ‘the image’ and the ways in which images become etched in the public imaginary. With reference to Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others, Tulloch and Blood write incisively about the images that were generated around the Kosovo conflict. Kosovo was not simply a bloody conflict between warring parties, but an exercise in propaganda, a means by which the global news industry told a story that would ingratiate the strategic interests and cultural imperialism of first world powers.

Not surprisingly, Icons of War and Terror devotes an entire chapter to the Abu Ghraib photographs. Abu Ghraib, we recall, was the prison expropriated by the invading Coalition forces in Iraq in 2003. Global attention was drawn to the prison when in April 2004 Sixty Minutes II ran a story about prisoner abuse. The story presented a series of photographs that had been taken by US reservists who had been appointed as prison wardens.

Western and Arabic critics of the Coalition invasion and occupation of Iraq regarded the photographs as particularly heinous. Not only did the images expose the brutal abuse of the prisoners, but they came to represent the inhumanity and absurdity of the whole war project.

Tulloch and Blood’s analysis of the photographs, and their political context, acknowledges the complex ways in which war ‘icons’ may be read by different audiences. However, the final thrust of their discussion—in accordance with their own critical objectives—locates these variable interpretations within a fairly straightforward critical model.

For Tulloch and Blood, however, the Abu Ghraib photographs were ‘iconic’ inasmuch as they ultimately distilled debates about the Iraq War. Paradoxically, while appearing to fortify the anti-war arguments, the photographs were ultimately re-appropriated by the supporters of the Iraq invasion, and presented as merely aberrant. As aberrations, the photographs could be condemned by the US government, and the perpetrators of the war crime could be punished accordingly. Order was restored by associating the photographs with deviant behaviour and deviant military personnel. The conservative, corporate media seems to have supported this position.

Tulloch and Blood take us through some of the diverse analyses of the Abu Ghraib photographs. But the discussion is never fully synthesized or reconciled with the overall objectives of the book. For all its strengths, I confess to feeling a little let down by the discussion on the Abu Ghraib photographs—particularly in terms of the question of the warden-photographers’ agency and the ethical-political issues it entailed.

Specifically, the analysis of Abu Ghraib sets up a series of positions, but there is little detailed explanation of how these positions can be reconciled with the framework that Icons of War and Terror has adopted. My own study of the photographs alerted me to the complexity of this case. It also alerted me to the problematics of ‘representation’, and the ways in which the ‘right to represent’ becomes blurred, as all things, in war.

This is not simply a case of the ‘first casualty’ principle, or whose truth is privileged in the extreme conditions of lethal violence. Important as these questions are, I am equally concerned about the ways in which the story of Abu Ghraib became so contorted and sexualized within the first world media. For me, this is also at issue with photos like the death of Neda Soltan and its appropriation for the visual pleasure of first world audiences.

The wardens of Abu Ghraib were playing with an image industry that they didn’t understand. In many respects, they were indeed ‘doing their job’, following orders, consigning themselves to the great US war machinery. Simultaneously, they were participating in a pleasure industry, the great mediasphere to which we are all condemned. While there is no doubt that the inmates at Abu Ghraib were tortured and traumatized, this was the torture of the global mediasphere as much as an exercise of warfare and extreme violence. To this end, the wardens at Abu Ghraib were victims, as much as perpetrators, of a system of violence that is predicated on differentials of pleasure.

The wardens sought to secure themselves in an extremely violent and largely absurd human situation. Given the ubiquity and epistemological force of the global media, it should not surprise us that they turned to ‘mediation’ in order to secure and stabilize their sense of self—and the pleasures that were their national birthright.

This intermingling of pleasure and violence is not addressed in any detail by Icons of War and Terror. However, this limitation doesn’t compromise the significance or force of the study. I found Icons of War and Terror extremely worthwhile. It was very readable and an intelligent analysis of complex problems. It is certainly a book that should be coupled with Susan Sontag’s work and the range of other quality analyses of the current incarnation of warfare and lethal violence.

—

Jeff Lewis is Professor of Media and Cultural Politics at RMIT University. He is author of Language Wars, Crisis in the Global Mediasphere, and Global Media Apocalypse.