Prices of world oil have made astonishing ascents and descents in the last four decades. The price stability that had characterised the world oil market since the post-war era came to an end after 1970 with changes in the international political climate. The 1973 Arab-Israeli war and the Iranian Revolution of 1979 disrupted the market, and caused prices to soar manifolds before the end of the 1970s. Prices reached an all time low in 1986 due to overabundance of supplies following the 1979 crisis. The erratic trend in prices has continued well into the post-Cold War era. The 1990 Gulf crisis brought a new peak in prices, and decline in prices came after 1997 when the Asian financial crisis set in.

The paper reviews the changing patterns of world oil prices through the study of four crises in the oil industry: the 1973 price quadrupling; the 1979 price doubling; the 1986 price decline; and the 1990 price rise. Each of these crises had been triggered by some political development in the oil producing Middle East: the 1973 crisis set in after the Yom Kippur war; the 1979 crisis followed the Islamic upheaval in Iran; the 1986 crisis precipitated in the wake of the Persian Gulf War; and the 1990 crisis came about by the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. This paper seeks to establish the relationship between these political developments in oil exporting countries of the world and subsequent changes wrought in prices and production of world oil.

Background to World Oil: The 50s and 60s

Control of Oil: The Reign of the Majors

The control of oil has two aspects: price stability and access. Price stability does not necessarily mean stable prices; it implies only that prices move smoothly, without drastic jumps, roughly in line with world inflation and towards the cost of alternative sources of energy. Access is defined as the availability of supplies in sufficient quantities over time without major disturbances. (Maull 1981)

Since the end of the World War II until the 1970s, the world of oil was controlled by a consortium of seven very large international oil companies, known as the Seven Sisters[1]. The seven Majors together controlled a large share of world oil through their concessions in the Third World producing areas, notably in the Middle East, which then held over half of world’s known crude oil reserves. The Majors produced, transported, refined, and distributed the bulk of internationally traded oil, and held the technical and commercial know-how needed to explore, develop, and market oil. The Majors run their business successfully by merging the disparate interests of producers and consumers. This they achieved by satisfying demands of both producer and consumer governments through the benefits of growing quantities of oil traded, and by integrating their companies vertically into the structure of market firms.

Throughout the 50s and the 60s, the Majors enjoyed an oligopolitstic[2] status in the international oil market. They established a unified world price structure at levels much above production costs, but low enough to conquer new markets for petroleum products. Overall, the oil market was insulated from politics, and whenever the insulation broke down, the Majors tactfully handled the problems caused by political disturbances. Thus the seven giant international oil companies ensured supplies that world oil demands were thoroughly met with constant, and that access to oil reserves in the host countries was never hindered.

Market Structure of World Oil: Some Contradictions

The oil market boasted stabilized prices throughout the period of 50s and 60s. Price fluctuation, however, was not improbable. The structure of the world oil market contained some inherent contradictions that had high likelihood of putting pressure on the stable prices.

- Though international oil companies controlled most of the trade in crude oil, and their access to oil reserves was also unhindered, this advantageous position was constantly under stress because of political developments in the producer countries. Since major reserves of oil were located within the territories of the Third world countries, access to this oil for the international oil companies rested on the extent to which the host countries were willing to concede their national sovereignty over the oil-rich areas as well as the economic and political issues involving procurement of that oil. As Third world countries emancipated themselves from Western colonial domination and realised complete political and economic independence in the first two decades after the World War II, to trespass their sovereignty became an increasingly tough task.

- Though trade in oil required a certain degree of conformity between interests of producers and consumers, yet there was contrast between the motives driving the international companies into oil exploitation and those driving producer governments into consenting to the exploitation. The Majors had a thoroughly commercial approach to oil projects: they saw oil reserves only as sources of profits. Producer governments however saw oil wells as national treasures, having more than just monetary value. (Adnan al-Janabi 1980) Thus while Majors adopted an unremitting attitude over drilling out oil, owners exercised more reason over the rate at which reserves were emptied.

- Oil companies made extraordinary incomes because of the large difference between market prices and production costs. Those incomes were a glaring reminder to producer governments that distribution of income between the companies and themselves had to be shifted in their favour. Though producer governments progressively maximized their profits in the 50s and 60s (Adelman 1972: 207-208), national instincts prompted them to take measures to accelerate the process further. When the international companies took counter measures to revert the process, a cartel of oil producing countries was founded in 1960 as a direct response. The Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) was an initiative by producer governments to take greater control of their own oil, and have greater say in matters of production, export, supplies, and prices of their oil in the world market. With the founding of OPEC, the Majors lost their edge in bargaining oil prices. After 1960, it was the producer governments which quoted prices of world oil. (Campbell 2005: 246)

- While West’s dependence on OPEC oil increased throughout the 50s and 60s, its ability to control the politics surrounding the world oil market constantly declined. Thus market structures themselves become increasingly open to challenge. The structure of the oil market was sustained on Western capacity to manoeuvre domestic politics of the producer governments. For example, when the regime of the oil companies was challenged in Iran from 1950 to 1953, it was re-established through direct intervention by the Western powers. [3] But this capacity to politically manipulate oil-rich regions declined throughout the 1960s because of changes in world politics. The rise of Soviet Union as challenger to Western hegemony, the powerful forces of nationalism within the Middle Eastern countries, and the devolution of economic and political power within the Western alliance system, all contributed to the loosening of Western grip over Middle Eastern politics. Meanwhile producer governments tightened control over their resources: through training programs they acquired knowledge and expertise, through changes in terms of cooperation with the Majors and newcomers they developed their own operational capacity; and through OPEC they increasingly coordinated their policies, thus undermining the ability of international oil companies to play off one producer against another. (Maull 1980)

Instability in World Oil: The 70s

Structural Transition in the Oil Market: From 1970-73

By the end of the 60s, the relationship between oil Majors and producer governments had tilted decisively in favour of the latter. However, it was only in the 70s that producer governments became conscious of their leverage in dictating the terms of oil trade. Two changes, enacted in the first three years of this decade, decisively transformed the dynamics of world oil. First, host countries and oil companies negotiated a deal to substantially raise oil prices at the beginning of the decade and only in small, regular intervals thereafter till 1975. (Rouhani 1971) This measure, however, did not reach fruition because revenues per barrel oil for OPEC governments increased in the wake of political unrest in the Middle East stirred by the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, and OPEC governments were unwilling to forgo the new per barrel profit because of which they became disinclined to raise oil prices worldwide.

Second, producer countries felt an increasing desire to control their economic destinies, just as conditions in the oil market change in such a way as to allow them to do so. Perhaps this was no coincidence: the desire may have been all along, but suppressed as long as it looked unattainable. (Chichilinsky and Heal 1984: 48) Producer governments secured sizeable stakein their oilreserves and produce, through negotiated participant agreements and unilateral nationalisation of their oil industries. OPEC oil continued to be managed by the international oil companies, yet now there was direct involvement by OPEC governments – in production, refining, and transport of their oil – through national oil companies.[4] By 1973, the face of world oil had changed beyond recognition from the stabilized prices repute characterising it for almost a century before this.

Quadrupling of Prices: The 1973-74 Oil Crisis

The first modern crisis in world oil raged in 1973, when several Arab members of OPEC placed an embargo on oil exports to the US in response to the latter’s support for Israel in the 1973 Arab-Israeli war. The delicate balance between demands and supplies was disrupted, and prices increased to nearly four times of what they were.[5] Initially, many thought that OPEC had blundered and was pricing itself out of the market. They believed that being a cartel, OPEC had always been unstable, and with the latest quadrupled prices, both OPEC and oil prices were heading towards collapse. (Freedman 1974) Others argued that it was not the OPEC but the US that had blundered: instead of opposing increase in prices, it had actively encouraged one. This could have been due to the covert alliance between Henry Kissinger and the Shah of Iran. (Greenberger 1983: 21-22)

Apart from the claims of blundering behaviour, two theoretical explanations compete to account for the causes of this astounding event. The first explanation argues that OPEC effectively cartelized the world oil market, exploiting its power to raise prices above competition levels by restricting production. (Pindyck 1978) In other words, OPEC monopolised the oil industry, controlled the amount of production, and quoted the prices of oil in the world market. The other explanation argues that OPEC was largely irrelevant as an organisation and that its members acted competitively. The oil market was tight way before the Arab-Israeli war. OPEC’s prices were well below those in the spot market, a freely competitive market in which hardly 10% OPEC oil was traded. (Gately 1984: 1101) The price quadrupling merely reflected a shift in the market conditions in favour of OPEC. This shift was underway since late 1960s, but it came to the fore only in the face of the 1973 crisis: world oil demand had been increasingly rapidly, non-OPEC production was stagnant and extraction costs were increasing, and the demand for OPEC oil surged.

The latter explanation, focusing on the competitive nature of the oil cartel, has two variants. One variant argues that increase in prices was the natural consequence of shift in property rights from oil Majors to producer governments in the late 60s and early 70s. When the Majors owned the oil reserves, they had high discount rates on prices, because they feared expropriation from the oil business. But producers, on acquiring ownership of their reserves, not only had lower discount rates but arrested their production capacity, in order to conserve their reserves. The outcome of the two policies was an inevitable increase in prices. (Johany 1980) Some scholars contest this view, arguing that OPEC countries deliberately cut-back their production to raise prices and get more profits for their oil and that they had less pressure to cheat as higher prices made them financially better. (Adelman 1982: 39)

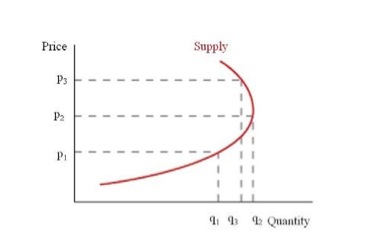

The other variant argues that OPEC behaviour is best understood as a backward-bending supply curve meaning cut backs occur if oil prices rise above a specific level so countries satisfy certain, or “fixed” to be exact, target revenues for their internal investment use. In Table 1, any increase in the price above P2 would result in a cutback in production, as the producer desires a fixed level of revenues. (Al-Qahtani, Balistreri and Dahl 2008) Thus prior to 1973, the relatively low price was determined by the intersection of demand and upward-sloping (lower) portion of the OPEC supply curve. With world economic growth, the demand curve shifted out far enough to intersect the backward-bending (upper) portion of the OPEC supply curve, at a price several times higher than before. (Cremer and Salehi-Isfahani 1980; Tecee 1982)

Table 1. Backward-bending Supply Curve

(Cremer and Saleh-Isfahani 1980, Adelman 1982, Griffin and Tecee 1982)

Source: Al-Qahtani, Ayed, Balistreri, Edward, and Dahl, Carol (March 29, 2008), “Literature Review on Oil Market Modelling and OPEC’s Behaviour”, Division of Economics and Business, Colorado School of Mines, Golden Co. 80401.

The Aftermath of Price Quadrupling: The 1974-78 New Regime

Following the worldwide oil crisis, a new regime established in the international oil market that held for the next four years. This time, world oil came to be dominated by producer governments united in their policies under the oil cartel, OPEC. The Majors continued to play an important role in producing, exporting, and marketing the bulk of OPEC oil, but they no longer exercised control over either production levels or prices. The Majors lost their traditional power of tapping oil in the OPEC territories, but nevertheless, were compensated with extraordinary increase in profits. The producer governments and the international oil companies thus entered into an association of mutual gain.

OPEC became the sole arbiter of world oil prices, and Saudi Arabia became the predominant voice within OPEC. Saudi strategy in the oil business was to keep production levels sufficiently high so as to meet international demand for oil. Saudi Arabia shouldered the burden of adjustment to the slackening demand for OPEC oil. It also exerted considerable pressure on fellow OPEC countries over prices by, implicitly or explicitly, threatening to unleash all its production capacity and flood the market. Saudi government felt a responsibility for, and a growing stake in, the wellbeing of the world economy. The large capital surplus it invested in the West was motivated by this desire to partake in strengthening the international market. Nevertheless, it was also motivated by the realisation that a severe economic depression in the West could economically and politically threaten the cartel members: economically, because it could dry out demand for OPEC oil, and, politically, because it could dramatically change the existing political structure and balance-of-power between East and West. (Dawisha 1980) Saudi Arabia therefore bargained in world oil prices to keep them by and large stabilized.

Saudi Arabia’s preeminent position in OPEC was solidified by certain developments in Middle Eastern politics. After 1973, United States became the leading peacemaker in the Arab-Israeli conflict, which seemed to be, for the first time since the 50s, on the path of resolution. The disengagement agreement following the 1973 war vastly strengthened United States’ position in the Middle East. Egypt became a coveted friend and ally of the United States in the Middle East. Besides American ascendancy in OPEC’s regional politics, Egypt’s cooperation with Saudi Arabia pointed to a shift in the gravity of Middle East towards a conservative moderate centre. Under such a political arrangement, the advantages of Saudi Arabia’s foreign policy – oil, money, Islam and political clout with Washington and Cairo – could be exploited to the full, while its weaknesses – military vulnerability, small population, problems of long term political stability at home – remained peripheral. (Maull 1981)

Market Structure of World Oil: Some New Characteristics

The new regime in world oil was characterised by several features that marked a drastic shift from the market structure that prevailed before the 70s.

- Producer governments acquired total control of their crude oil reserves, production levels, and depletion rates. Levels of production rested on decisions of OPEC governments, which in turn depended on the dynamics of OPEC’s regional politics. Thus internal political developments of Middle Eastern countries had immense bearing on the health of the world oil market.

- Prices were consensus based: they were determined after consultation and coordination among all OPEC members. (Mikdashi 1976) Bargaining in prices was most decisively influenced by the leading OPEC countries, which between 1974 and 1979, were the four largest Gulf oil producers – Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq and Kuwait.

- Saudi Arabia enjoyed a predominant position within OPEC. This status was acquired on account of its huge resource base, high production capacity, and ability to absorb the financial consequences of fairly wide fluctuations in export levels. Saudi Arabia’s take on prices was crucial in determining prices of world oil.

- The new regime functioned well because of a concurrence of favourable developments in Middle Eastern politics: domestic stability; regional dominance of the Cairo-Riyadh and Cairo-Tehran-Riyadh axes; and progress on the resolution of the Palestinian crisis. Since market equilibrium was achieved through such a delicate balance of political conditions, any change in the latter heralded adverse changes for world oil.

Table 2. Trends in Crude Oil Ownership 1950-1979a

| 1950 | 1957 | 1966 | 1970 | 1979 | |

Seven Majors |

98.2 % | 89% | 78.2% | 68.9% | 23.9% |

| Other International Oil Companies | 1.8% | 11% | 21.8% | 22.7% | 7.4% |

| Producing Country National Oil Companies | ** | ** | ** | 8.4% | 68.7% |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

aExcluding ownership of crude oil supplies in the United States and the Communist countries

**Negligible

Sources: Adelman, Morris A. (1972), “The World Petroleum Market”, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 80-81. Cited in Levy, Brian (Winter 1982), “World Oil Marketing in Transition”, International Organisation, 36 (1): 117.

The Doubling of Prices: The 1979-80 Oil Crisis

In 1979, when the Islamic Revolution disrupted Iran’s production, oil prices doubled and panic ceased the world market. The international oil industry was crisis struck, a second time in the same decade. A parallel development of much consequence was the Egypt-Israel peace treaty following the 1978 Camp David Accords. It led to the disintegration of previous patterns of political cooperation in the Middle East, and formation of new alliances. The two political events debilitated Saudi Arabia’s strategic dominance in the Middle East, and thereby to a considerable extent within the OPEC.

The 1979-80 oil crisis essentially reflected the fragmentation that had come to internally characterise the oil market and the political structure surrounding it. The net result of market disintegration was huge increase in prices and a highly diffused price structure. Confronted with tempting opportunities to increase revenues, OPEC governments decreed unilateral price increases which led to rattling escalation in the overall OPEC price structure. Cohesion and cooperation among OPEC members was reduced to a consensual ‘price range’, which was rather a camouflage for gross disagreement over prices. Even Saudi Arabia’s attempts to break the ascent of prices came to nothing. It too was ultimately forced to go along with the OPEC majority.

There are two theoretical explanations for increase in prices during 1979-80. The first view argues that OPEC consciously exploited the Iranian disruptions to extract still greater profits from the already tight market. In a decisive move, Saudi Arabia pulled back its production levels thus leaving enormous quantities of demand unmet. This restricted production was the precise cause of price doubling, not the Iranian Revolution. (Adelman 1982: 55) This explanation is consistent with the dominant producer theory of OPEC (Griffin and Tecee 1982): Saudi Arabia sets the price, it allows other OPEC members to produce what they wish, and acts as the ‘swing producer’, varying its own output to absorb demand and supply fluctuations so as to defend the price. (Gately 1984: 1103) A variant of the first view argues that increase in prices was engineered by Saudi Arabia, but the country’s oil policy – its reluctance to assert leadership within OPEC – was dictated by more complex political constraints it was facing at this time. (Moran 1982: 110) The second view argues that OPEC was irrelevant as an organisation, and that prices rose because of the underlying demand and supply conditions. OPEC discipline had broken down, and international oil market was in mayhem: producer governments kept hiking their oil prices and consumer governments kept stockpiling in speculation of future scarcity. (Stobaugh and Yergin 1980)

Hyperpluralism[6] in World Oil: The 80s

The Aftermath of Price Doubling: The 1980-83 Decline in Demand

Following two crises in world oil, by 1980, prices had increased to fivefold of what they used to be in 1973. As the decade progressed, the world’s oil demand started falling dramatically. Total world oil demand fell by 20 percent, while OPEC oil demand fell way more sharply than it had in the aftermath of the 1973-74 price quadrupling.[7] The decline in OPEC oil demand is attributable to several factors. Part of this drop was due to the worldwide recession of 1981-83, during which the world economy languished, still unrecovered from the 1979-80 price shock. Another cause was increase in energy conservation, achieved by consumer countries in response to rise in prices and interruption in supplies throughout the 70s. In Western industrialised countries, between 1973 and 1984, the ratio of energy consumed in relation to Gross National Product fell by 19 percent. (Flavin 1985: 42-43) In addition to increased efficiency of energy consumption, there was also increase in use of alternative energy sources. Between 1973 and 1984, the use of coal, natural gas, nuclear power, and renewable energy resources increased greatly, while oil’s share of world energy use fell from 41 percent to 35 percent. (BP 1986)

Another explanation for diminishing demand in OPEC oil was expansion in non-OPEC production. (Georgiou 1987: 297) In 1974-75, following the price quadrupling crisis, OPEC oil demand had dropped by 15 percent. But the drop in 1980-83 was more than triple that figure, the enormous difference being partly because ofincrease in non-OPEC supply. Between 1975 and 1985, non-OPEC countries increased their share of world total oil production from 48 percent to 71 percent, with most of the increase coming from Mexico, the North Sea and the Soviet Union. (International Energy Agency 2005) Increase in non-OPEC supply had two main effects. First, non-OPEC countries were setting their own prices which were more responsive to market conditions and hence more competitive. Second, the number of crude oil producers increased significantly prompting dramatic adjustments in supply and demand patterns. The new suppliers, who ended up with more crude oil than required by contract buyers, secured the sale of all their production by undercutting OPEC prices in the spot market. The buyers, who became more diverse, were attracted by the competitive prices on offer since they were below the long-term contract prices. (Fattouh 2007: 4)

In 1980, another war shook the Middle East, this time between Iran and Iraq. Better known as the first Persian Gulf War, it lasted for eight long years during which it knocked out more OPEC production that had the 1979 political disturbance in Iran. But timing had much consequence for how the war impacted the oil industry. In 1980, stockpiles were at historic highs because of the previous crises in prices and productions, demand for OPEC oil was falling because of continued efforts to conserve fuel and use alternative energy sources, (Rose 2004: 436) spare capacity among OPEC producers was much, and therefore variation in prices was minimal.

Downturn in Prices: The 1986 Oil Glut

One of the major factors causing overabundance of world oil was OPECs inability to limit its production sufficiently to support a given price level. Between 1979 and 1982, demand for OPEC oil dropped by 40 percent, consequently all members decreased production by at least 20 percent. Nearly all OPEC members bore the brunt of limiting production, although certain members made larger cuts: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Libya reducing output by 65 percent, 60 percent, and 50 percent respectively. Yet even with this drop in output, prices continued to fall. This put pressure on producers to make up for falling revenues by increasing their output.

Eventually, towards the end of 1985, Saudi Arabia announced that in riposte to other OPEC members’ repeated violations of their respective production quotas, it would no longer play the role of ‘swing producer’ and would instead attempt to increase its share of world oil by selling oil at whatever prices the market would bear. As OPEC abandoned all production and pricing agreements, OPEC output rose by 25 percent, between 1985 and 1986.[8] (Gately 1986: 241-242) Of course, this only added to the world oil glut, causing oil prices to fall below $10 a barrel, which in real terms is lower than the $3 per barrel price that prevailed before the 1973 price shock. (Georgiou 1987: 298)

Market Structure of World Oil: The Retreat of the Oil Cartel

The fall in prices and OPEC’s failure to regulate the world oil market, reflected an underlying shift in the international oil regime.

- When the Majors had controlled the oil market, they held crude oil inventories as buffers against short run fluctuations in demand and supply, whereby their grip over the market could be increased. In times of falling prices, the Majors would add to their inventories, taking oil off the market, thus helping prices to firm up. In times of rising prices, they would draw oil from their stocks and place it on the market, thus relieving pressure on prices. After the 1979-80 prices doubling, however, the Majors began to slowly draw from their oil inventories till they were no longer effective against shocks in the short run. Far from stabilizing the market, the international oil companies exacerbated its cyclical movements: when a glut seemed imminent, they tended to shy away from buying crude oil and instead drew down their inventories, adding to the downward pressure on spot prices and heightening the glut. Producer governments encouraged this trend through creation of national reserves, which though meant to stabilize the supplies during crises, ended up restricting release of the surpluses to counteract market swings. Thus OPEC felt an ever increasing burden of regulating the market. (Georgiou 1987: 301)

- OPEC’s position was further weakened by the establishment of a new price structure – the “netback” agreements announced by Saudi Arabia in 1985. In the new arrangement, crude oil prices were made to depend on prices of products obtained from crude oil, i.e. sale of oil derivatives determined the sale of oil in the spot market. Such an arrangement favoured the buyer at the cost of the seller, because it was the seller who absorbed the adverse price movements that occurred in-between the times of sale of oil and that of its products. This is why the 1986 decline in prices was more precipitous than warranted: an increase of merely 5 percent in world oil supply led to a 60 percent drop in prices. (Amuzegar 1986: 15) OPEC therefore became even more vulnerable to price fluctuations.

- Following the 1986 crisis, Saudi Arabia designed a new OPEC agreement to fix prices, and coordinate and reduce OPEC production accordingly. The mechanism seemed successful at first since prices rose in the spot market. But no sooner had they risen, than they fell because supplies were constantly in excess. This was evidence that certain OPEC members were persisting in overproduction and that oil companies were drawing down the inventories they had built up when oil prices fell to an all time low in early 1986. Despite prices firming up afterwards, the market was still far from long-term stability.

- Towards the end of the 1970s, OPEC producers advanced into downstream activities, such as refining of oil, production of petrochemicals, transport of oil and oil products, and, even retailing of final products to consumers. This marked a departure from OPECs traditional status in the oil market, as one of crude oil supplier – rest of the industry being left to the care of oil companies – to one with expanded activities, responsible for the workings of the overall market. When setting crude oil prices, they had to now take into account product prices and refinery margins. In the short run, this added yet another factor to OPECs already complicated task of regulating prices. Consequently it accentuated oil market instability.

The lesser developments in the market combined to produce a structural shift – the burden of regulating world oil moved from the international oil companies to OPEC. But the change came about at a time when increasing non-OPEC production and declining world oil consumption pushed the market beyond OPEC control, and made it difficult for OPEC to shoulder this burden. In the short run, the market was assailed by greater volatility and instability, and prices became susceptible to sliding further than to scaling.

Blood and Oil: The 90s

Low Prices and High Politics: The 1990-91 Oil Crisis

Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait at the very beginning of the 90s was an astonishing show of the lengths to which states were willing to militarily engage in pursuit of oil. The Gulf crisis which broke out in August 1990 was, to a large extent, a conflict about controlling oil, dictating prices, and amassing revenues. Apart from the broader political and regional objectives of Saddam Hussein, the most immediate and critical intent for invading Kuwait was to rescue Iraq from the economic calamity that was threatening its political regime.

Excruciatingly low prices in world oil throughout the 80s had limited the flow of revenues to Iraq. Compensation for low revenues could come about only through increase in production. But expansion in production capabilities was unaffordable for the Iraqi government in the late 80s. Crazed by the need to augment revenues, Iraq demanded OPEC members to lay down stringent production policies that would readily raise prices. Discord arose at once with Kuwait and UAE, as the two were singled out as law-breakers, whose unbridled production caused havoc in the market in the first half of 1990. (Marbo 1994: 242) Kuwait had apparently favoured low oil prices, and in the short run, it had managed to recompense the loss in revenues caused by low prices, through enormous increase in production.

The rationale for supporting low prices lay in the equation that decreased prices would increase demands, and secure, if not raise, the share of oil in world energy consumption. This would in turn arrest the trend of exploring alternative energy sources and implementing energy conservation measures. More importantly, this would contribute to the expansion of the world economy; economic growth being the most powerful index of increase in demand for oil. (Marbo 1994: 245) Saddam saw low prices as highly detrimental to Iraq’s interests. To evade being economically sidelined by the low price band-wagon, he coerced his military might against Kuwait. In response to Iraq’s aggression, an embargo on dealing in all exports from both Iraq and occupied Kuwait was imposed almost immediately causing prices to peak after an entire decade of lying low.

Market Structure of World Oil: The Demise of OPEC

The Gulf crisis left OPEC further hollowed than it had been in the 80s. Indeed, the cartelization efforts of the previous decade had come to little more than nothing. Decision-making on prices circumvented consensus and policies on production levels remained unimplemented. Apart from the damage already done by the immediate crisis, two changes in the course of the 90s further undermined OPEC’s role in world oil.

- The Gulf crisis disturbed the output distribution between OPEC members. Saudi Arabia and UAE had managed to increase their production significantly throughout the 80s, and continued to do so even during the 1990 crisis. After the crisis was brought under control, the market required them to limit output levels in order to accommodate Kuwait back into the industry without upsetting prices. However, both countries were unwilling to restrict production and this disregard for OPEC, rendered the cartel policies on production quotas ineffective.

- The Gulf crisis made OPEC members politically much more dependent on US and Western powers. Experiencing the 1990 war, OPEC countries recognized the enormous threat that regional rivalry posed to their national security and to the oil business at large. With US’s spectacular show of military prowess in liberating Kuwait, Arab members of OPEC in particular came to look upon US as the guarantor of regional peace. Relying on external powers to resolve regional disputes prevented OPEC members from acting as a cartel during the rest of the 90s decade. OPEC was unforthcoming in taking any conspicuous measure to administer prices or limit production.

References

Adelman, Morris A. (1972), “The World Petroleum Market”, Baltimore: John Hopkins Press.

Adelman, Morris A. (1982), OPEC as a Cartel, in Griffin, James M. and Teece, David J., eds. (1982), “OPEC Behaviour and World Oil Prices”, London: George Allen and Unwin, 37-63.

Ahrari, Mohammed E., “OPEC and the Hyperpluralism of the Oil Market in the 1980s”, International Affairs, 61 (2): 263-277.

Al – Janabi, Adnan (Summer 1980), “The Supply of OPEC Oil in the 1980s”, OPEC Review, 8-26.

Al-Qahtani, Ayed, Balistreri, Edward, and Dahl, Carol (March 29, 2008), “Literature Review on Oil Market Modelling and OPEC’s Behaviour”, Division of Economics and Business, Colorado School of Mines, Golden Co. 80401.

Amuzegar, Johangir (July-August 1986), “Cheap Oil: Whose Trojan Horse”, OPEC Bulletin, 15.

Bobrow, Davis B. and Kudrle, Robert T. (March 1976), “Theory, Policy and Resource

Cartels: The Case of OPEC”, Journal of Conflict Resolution, 20 (1), 3-56.

BP Statistical Review of World Energy (June 1986), London.

Campbell, Colin John (2005), “Oil Crisis”, Multi-science Publishing Co. Ltd., Essex, UK, Chapter 11.

Chichilinksy, Graciela and Heal, Geoffery (Spring 1984), “The World Oil Market, Past and Future”, Columbia Journal of World Business, 47-52.

Cremer, Jacques and Salehi-Isfahai, Djavad (1980), “Competitive Pricing in the World Oil Market: How Important is OPEC”, Mimeo U. of Pennsylvania.

Dahl, Robert A. and Lindblom, Charles E. (1953), “Politics, Economics and Welfare”, New York: Harper & Row.

Dawisha, Adeed (1980), “Saudi Arabia’s Search for Security”, Adelphi Papers, 158: 27-30.

Doran, Charles F. (February 1980), “OPEC Structure and Cohesion: Exploring the Determinants of Cartel Policy”, The Journal of Politics, 42 (1), 82-101.

Dye, Thomas R. (1966), “Politics, Economics and the Public”, Chicago: Rand McNally.

Edwards, Corwin D. (1944), “Economic and Political Aspects of International Cartels”, prepared for Subcommittee on War Mobilization of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs, Washington DC: US Government Printing Office, 11.

Fattouh, Bassam (March 2007), “OPEC Pricing Power: The Need for a New Perspective”; Oxford Institute of Energy Studies, Registered Charity, No. 286084.

Flavin, Christopher (July 1985), “World Oil: Coping with the Dangers of Success”, Worldwatch Paper 66, Washington DC, 6-7.

Freedman, Milton (March 4, 1974), Newsweek.

Gately, Dermot (September 1984), “A Ten-Year Retrospective: OPEC and the World Oil Market”, Journal of Economic Literature, 22 (3): 1100-1114.

Georgiou, George C. (Spring 1987), “Oil Market Instability and a New OPEC”, World Policy Journal, 4 (2) : 295-312.

Greenberger, Martin, ed. (1983), “Caught Unawares: The Energy Decade in Retrospect”, Cambridge, MA: Balinger.

Levy, Brian (Winter 1982), “World Oil Marketing in Transition”, International Organisation, 36 (1): 113-133.

Marbo, Robert E. (Winter 1975-76), “OPEC after the Oil Revolution”, Millennium 4, 191-199.

Marbo, Robert (Spring 1994), “The Impact of the Gulf Crisis on World Oil and OPEC”, International Journal, 49 (2) After the Gulf War, 241-252.

Moran, Theodore H. (Winter 1976-77), “Why Oil Prices Go Up: The Future OPEC Wants Them”, Foreign Policy, 25, 58-77.

Maull, Hanns W. (Spring 1981), “The Control of Oil”, International Journal, 36 (2): 273-293.

Maull, Hanns W. (1980), “Europe and World Energy”, University of Sussex, London, Chapter 9.

Mikdashi, Zuhayr, The OPEC Process, in Raymond Vernon edited, “The Oil Crisis”, New York, 203-216.

Mohnfeld, J. H. (August 1980), “Changing Patterns of Trade”, Petroleum Economist, 329-332.

Moran, Theodore, Modelling OPEC Behaviour: Economic and Political Alternatives, in Griffin, James M. and Teece, David J., eds. (1982), “OPEC Behaviour and World Oil Prices”, London: George Allen and Unwin, 37-63.

Pindyck, Robert S. (May 1978), “Gains to producers from the Cartelization of Exhaustible Oil”, Review of Economic Statistics, 60 (2): 238-251.

Rose, Euclid A. (Spring 2003), “OPEC’s Dominance of the Global Oil Market: The Rise of the World’s Dependency on Oil”, Middle East Journal, 58 (3): 424-443.

Rouhani, Faud (1971), “A History of OPEC”, Praeger, New York, 15-25.

Smith, James L. (Summer 2009), “World Oil: Market or Mayhem?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23 (3): 145-164.

Snider, Delbert A. (1967), “Introduction to International Economics”, Homewood III. : Richard D. Irwin, 252-255.

Stobaugh, Robert and Yergin, Daniel eds. (1980), “Energy Future”, New York: Ballantine Books.

[1] Exxon, Gulf, Socal, Mobil, Texaco, Royal Dutch Shell, and British Petroleum.

[2] Spot Market is that in which produce is traded for immediate delivery. It differs from Future Market in which delivery is made at a future date.

[3] In 1951, Iranian Prime minister Mohammed Mossadegh nationalized Iran’s oil industry to protect it from the exploitative British-owned Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC). To restore their share of Iranian oil, Britain and US plotted a coup d’état to overthrew the Mossadegh government, and established a puppet autocracy of the Shah. This also ended the possibility of Iran’s alliance with Soviet Union.

[4] Direct exports by OPEC national oil companies increased from 0 to 5 % between 1970 and 1973 to reach an estimated 50 % in 1980. (Mohnfeld 1980)

[5] Oil prices soared from $12 in October 1973 to $53 per barrel in four months. (Smith 2009: 145)

[6] “Hyperpluralism describes an extreme form of pluralism of the oil market. For instance, until the late 1970s, 80-90 per cent of OPEC exports were purchased by major oil companies. This virtual monopoly was so drastically altered in the 1980s that each petroleum-exporting country was transacting with 20-40 customers, including previous concessionaires, American independents, and oil companies from Japan, Western Europe, and the Third World countries. Similarly, the list of sellers, in addition to OPEC, included non-OPEC members such as the United Kingdom, Norway, Mexico, the Soviet Union, China, Egypt, Malaysia; and minor African states.” (Ahrari 1986).

[7] Between 1979 and 1983, however, demand for world oil fell from its 1979 peak of 65 million barrels per day by around 10 percent. For OPEC, this fall-off was even more serious than these figures suggest; from a 1979 peak of 31 million barrels per day, world demand for OPEC oil has fallen almost 50 percent. (Flavin 1985: 6-7)

[8] The increase between August 1985 and July 1986 was 4 million barrels per day. (Georgiou 1987: 298)

—

Written by: Ms. Aparajita Goswami

Written at: Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India

Written for: Dr. Jayati Srivastava

Date written: April 2011

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Conceptualising Europe’s Market Power: EU Geostrategic Goals Through Economic Means

- The (Un)intended Effects of the United Nations on the Libyan Civil War Oil Economy

- Casting Light on EU Governance: Reflection and Foresight in an Era of Crises

- Institutionalised and Ideological Racism in the French Labour Market

- Water Crisis or What are Crises? A Case Study of India-Bangladesh Relations

- To Reform the World or to Close the System? International Law and World-making