Introduction

The division of British India into the two independent national states of India and Pakistan left deep scars in the region, yet often this is overlooked with a focus placed on celebrating independence. Drawing on Margaret Bourke-White’s The Great Migration: Five Million Indians Flee for Their Lives (1947), which documented the partition through photographs, allows us to draw out the narratives which compose modern Indian history.

Studies of the partition are divided between a focus on ‘high politics’ and ‘voices from below’. The study of Bourke-White photographic essay showcases how the reticence and reluctance on the part of high politics works to the formation of exclusionary practices and oppression. The high politics focuses on the political negotiations between the British, the Indian Congress and the Muslim League and excluded examining the consequences on individual’s lives. While standing in antithesis to the linear historical narratives of partition, the weaver’s diary (Pandey, 1991) silhouettes the literary writings of the partition. The rhetoric of high politics perpetuates the assumptions of statehood and sovereignty in order to institutionalize ‘power’ and ‘security’. Confining the issues of national borders to macro-level, the high politics represent the single concern. Whereas focusing on micro-level history enables us to counter the omnipresence of the nationalist power to open the space for the working of conflict and violence at the micro-level[ii].

To understand the 1947 Partition it is necessary to engage with the micro-level; which lays emphasis on the literary genres and cinematic representations. Somewhere in the process, the visual documentation of the 1947 Partition (except a number of rereadings[iii]) remains outside the domain of the critical eye. In order to open the discipline of documentary photography to Partition Studies, the paper uses Margaret Bourke-White’s Photographic Essay The Great Migration: Five Million Indians Flee for Their Lives. Working on the idea that the “text” is an open space, the visuals narrate the lived experience of struggle and violence only to critique the pre-conceived notions of nationalism. The semiotic understanding of visual representations locates the decentered subject to raise our attention to the politics between the periphery and center, and works to counter the legitimate truth anchored by political assertion.

The paper provides an alternative understanding of the impact of the 1947 partition by emphasizing the ‘history from below’ as an alternative to the grand narratives. The collection of Bourke-White photographs from Life magazine works as a powerful additional trope to add complexity to the issues of political moral sovereignty.

Bourke-White and the American Century

Margaret Bourke White, along with contemporaries Berenice Abbot and Walker Evans, took the discipline of documentary photography to unscaled heights. The establishment of the New Deal (1933-36) in the United States and the advent of technology challenged America’s mass media. Bourke-White’s documentary photography provided an alternate view to that given by America’s mass media. At the time Life magazine subscribed to an ethos of the “press-that-gives-the people-what-they-want” (quoted in Jessup 1969, 117). The magazine was conceived with carefully crafted strategies of representation: catering to the needs of upper and middle class; redefining national consciousness; and hinting at the growth of consumer realism.When Wendy Kozol hails the magazine as ‘realistic’ (1994, 10), she hints at the discerning strands of realistic consumer forces, which make it a highly political read.

Standing at the cusp of colonialism and modernism, the newly independent state of India is thrown to the challenges of partition. The political function to monitor the appropriate reality has worked to intersperse the historiography of partition with the ideal of a homogenized national culture. It is necessary to move away from the easy teleology of past, present and future and to investigate the paradoxes of individual freedom versus state control[iv]. The visual narratives embedded within the human sufferings challenge political science to confront them. Documentary photography straddles between visual beautification and an uneasy truth. The present paper is conceived with an understanding that the visual collection is able to capture and critique the social environment.

Luce outlines “pictorial journalism”, as, “a new language, difficult as yet unmastered, but incredibly powerful and strangely universal.” (Luce 1936, 1) Life was of interest to its readers not just because of its photographs but because of their juxtaposition with captions. The intensity of the former led to the “graphic ordering of the desire” (Stein, 1992) and the latter proposed to add empirical value to the reality expounded by the photographs. With the aid of captions and camera work, the paper shall discuss eight photographs from the photographic essay. Depending on the context, the photographs will be read individually or juxtaposed against each other.

Unmaking Domesticity

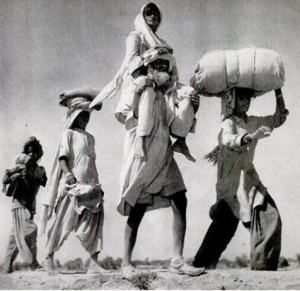

Bourke-White captures the unmaking of domesticity by taking close up photographs of the migrants. The very first photograph (pg.117) attempts to capture the warmth of family relationships, which secures the domesticity. She cleverly captures the refugees making the passage across the Western border looking straight into the camera and allows a child to do the same only to accentuate the pain. The anarchy is encapsulated in her caption “Spindly but determined old Sikh carrying ailing wife sets out on the dangerous journey to India’s Border.” Oblivious to the intricacies of domesticity as a constituent of social reality, the nationalist discourse build the notion of gender roles on the matrix of private chores and public affairs. During Partition, on the larger front of struggle to survive, the gender difference and the spatial dichotomy come to play a feeble role.[v]

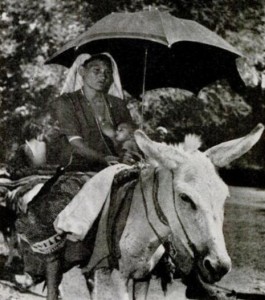

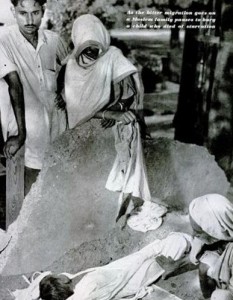

The photograph of a Mother and Child (pg. 123) is a quintessential picture of domesticity. The caption reads, “mother and child are part of caravan 25 days on road. More fortunate than most, woman can ride and has a umbrella for a shade as she feeds her baby.” The act of mother feeding the new born reinforces the belief that the future of any nation lies in the hands of young ones. Nevertheless Bourke-White goes onto draw into question this promise, when she ends her photographic essay with an image, which shows the burial of a new born child (pg.125).

The caption says, “As the bitter migration goes on a Moslem family pauses to bury a child who died of starvation.” It would not be an exaggeration to suggest that the visual narratives reveal the unmaking of domesticity, a palpable symptom of the external forces of political righteousness.

Designing Humane Sensibility

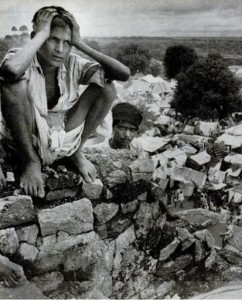

The division of the Indian subcontinent paved the way for the dual spaces of the centre and periphery. Bourke-White works to showcase how the periphery can relocate the logics of the centre. The photograph becomes a performance when the architectural designs accentuate the humane sensibility. The dilapidated walls of Purana Qila (pg.118), which served as a refugee camp in Delhi, situate the viewer in awe of the dislocation and depravity. The situation is punctured with heterogeneity and the wide array of make-shift tents and people engaged in a variety of activities, raises the feeling of antipathy towards the façade of high politics. The aesthetics of depravity is further aggravated when the caption declares, “misery of dispossessed is reflected in the face of this Moslem boy, perched on the wall of Purana Qila fortess in New Delhi. Below him are thousands of his unhappy fellows, who have fled their homes in terror are trying to survive until they can organize a convoy for a long march to Pakistan. In their squalid city of tents and tin-box they have almost no room to sleep and little to eat. They are surrounded by filth and many will die without ever leaving the camp.”

Sighting Agony

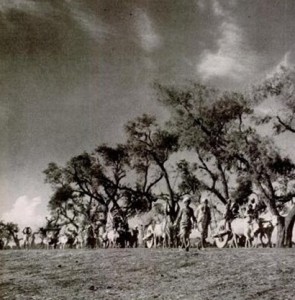

The agonizing landscape becomes a participant in the human vulnerability (pg. 120-121). Bourke’s camera mannerism gives a space to present a just photograph of the large scale wreckage caused by the event, “the emigrant train of crude wooden carts drawn by bullocks creaks across the barren land of the Punjab all day long. In this convoy, starkly silhouetted against the vivid Indian sky are 45,000 uprooted Sikhs on their way to the Ferozepore and Ludhiana district of the eastern Punjab. Unlike the US wagon-train pioneers, hopefully en route to a new land, these migrants have little to look forward to and are losing everything that they cannot carry with them. Despite the presence of an escort of Gurkha soldiers, thousands of sinking bodies along the road constantly remind the travelers that they may never reach safety.” (pg. 120-121) The large framework of her visual narrative does not include an unadorned emphasis on the individualism but the landscape- open sky and dried tress- as an embellishment is a showcase to the pain and suffering of the masses.

Decaying Body

On one hand, the theoretical framework of political discourse mystifies the family relations, on the other hand, it reduces the body, a performance in itself, to another archetypal instance of the hegemonic forces. Tempered by communal violence and abuse, the clinical body becomes the site of power play. The cultivation of fear by the communal sides on the body, which is open to contestation, works to expunge the signs of resistance. In a similar vein, the next set of three photographs (pg.123-124 i-ii), highlights subjugation of the body to decay.

It is imperative to locate how the politically saturated images of human pain are the voices of decadence and violence which necessitate a need to exploit the popular perspectives on aesthetics. The photograph (pg.123) includes the caption, “abandoned at roadside because they were unable to keep up with caravan, this aged Moslem couple and their four grandchildren have little hope of survival. The children father was killed by Sikh. Their mother was stricken with cholera and sent ahead by the truck in the hope that she might find medical care.” The almost crimpled naked body, a displacement of the concerns of beauty and etiquettes, changes into a formative pathological and criminal scene.

Both the communal sides play with the art of disciplining the body to detriment of the other. Embarking on the dramatic style, Bourke-White takes the close shots of skeletons lying half buried against the convoy of Moslems (pg. 124.i). The photograph comes with the caption, “The dead from a previous Moslem convoy lie rotting at the roadside next to the whitened bones of their buffaloes and bullocks, while another convoy marches past apathetically on the way from East to West Punjab. Here, marked by the bones and bodies, was the scene of a bloody attack by the Sikhs.” Interestingly, this particular photograph, as the caption suggest, can be read as an extension of the photograph on p. 121.

The aesthetics of depravity strip the body back to its bones and flesh. Bourke- White reinforces the anarchical tendencies when she captures the vultures feeding mutilated bodies against the background of untamed landscape (pg.124. ii). “The Vultures descend to tear at the bodies of four Moslem pilgrims who were murdered and left lying in a flooded field only 6 miles outside of Amritsar. Death has become so commonplace in this area that the harried emigrants seldom even turn to look at the spectacle of vultures or dogs feasting on human flesh.”

The fluid body at the disposal of communal ethos is not just a simple inscription of violence but a living archive that is home to the memory of violence.[vi] The political identity of the body (Scarry, 1985), when read within the parameters of aesthetics of depravity, once again reminds us of the irregular state practices.

Conclusion

Taking a cue from Stange on photography praxis, this paper has avoided reading the photographs as the final confirmation and has allowed the photographs to be, “the more truthful revelation of ambiguity” (Stange 1994:86). The ambivalence de-emphasizes the sovereignty of the political-economy structures. The hierarchy between the viewer and the subject of photograph evokes a romanticized view of the marginal. It is further argued that the temporary state of emotional outburst acts as the moment of social catharsis, where the viewer is led to gradual distancing from the horrors of violence. However, the idea of the paper is not conceived to address Sicily’s postulations, nonetheless with postcolonial choices the paper allows us to closely scrutinize the normalcy of the absolute truth.

The paper is an endevour to inaugurate the documentary photography on partition to the larger discipline of Partition Studies. Within the given array of literary writings and cinematic representations on the Partition, the visual representations can be read as an extension of language on struggle, violence and resistance. The visual narrative with the larger framework defined by unknown faces and anonymity stands at a distance from the literary texts, in the sense, latter tends to build a relationship while moving from self of the reader to the private life of the literary character. On the other side, the visual narratives are the slippage from private self of the viewer to the public domain of the photographic subject, which leads through the shared emotional anxiety.

Under the umbrella of visual economy, aesthetics of depravity and spectatorship the consumption of the image serves to disrupt the dominant social and political relationships.The attempt to deconstruct the visual narratives, as commentaries on both the cause and effect of historical events, raises a counter-voice to the celebratory account of certain victorious concept and power: the nation state and bureaucratic rationalism. (Pandey 1994, 214). The photographs showcase the interplay between the illuminated self and darkened realities. The visual space torn between the aesthetic of depravity and its implementation underpins the uneasy social reality.

The aim of the paper is not to establish concrete answers but to move towards what Partha Chaterjee (2012, 48) declares the “rise to prominence of the non-canonical and unsophisticated varieties of printed material [in the present case this is visual material] that the focus shifted away from intellectual or high literary history to the historical construction of national-popular which demanded entirely different principles of literary and aesthetic judgments.” The trimmed borders, once assembled by the authority, commodify the truth only to destabilize the ordered world. The visual representations are a conflict zone between the binaries of emancipation and surveillance; and beauty and depravity. These reconfigure the disenfranchised that are otherwise hallmarks of servility to the political elites. Questioning the disciplinary modes of governance, the image invites the viewer to transcend the rhetorical immediacy. The exercise is an endevour to contribute to the understanding of pluralistic identity of a decentered subject, which derails the motives of larger good propelled by the nationalists.

—

Dilpreet Bhullar is an MPhil. Research Scholar at the Department of Modern Indian Languages and Literary Studies, University of Delhi. While sharing keen interests in Post-Colonial Studies, Visual Ethnography and Cultural History, she works at the Visual Arts Gallery, India Habitat Centre, New Delhi.

Endnotes

[i] The proceedings of the paper were presented at the International Congress of Bengal Studies, held in December, 2011, Dhaka. A special thanks to Prof. Alok Bhalla and, Dr. Amitava Chakraborty, General Secretary of International Studies of Bengal Studies. Images Courtesy: Life Archive, 3.November 1947.

[ii] For further discussion on the study of conflict in the sociological terms see Croissant Aurel, and Christopher Trinn, Culture, Identity and Conflict in Asian and South Asian, International Cultural forum South Asian.

[iii] Khushwant Singh’s Train to Pakistan, New Delhi: Roli Books, 2006; Witness to Life and Freedom: Margret Bourke-White in India and Pakistan, New Delhi: Roli Books, 2010 have documented photographs from Bourke-White’s essay.

[iv] See Emile Durkheim’s The Rules of Sociological Method. 1938, The Free Press, New York.

[v] My argument is not evasive to the struggles of women and other gender sensitive issues which are dealt within Partition Studies. However, my present line of argument sketches the experience of loss, irrespective of gender discrimination, on the both sides of border.

[vi] Deepti Misra’s discussion on the novel What the Body Remembers in the essay The Violence of Memory: Renarrating Partition Violence in Shauna Singh Baldwin’s What the Body Remembers shows the woman body as subordinate to the patriarchy.

References:

- Chatterjee, Partha (2012), “After Subaltern Studies”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol

XLV11, No. 35, p. 44-49.

- Durkheim Emile (1938). The Rules of Sociological Method. New York: The Free Press.

- Elaine Scarry (1985). The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Guy Debord (1970). Spectacle of Society, MIT Press, Cambridge.

- Gyanendra Pandey (1994), “The Prose of Otherness”, Subaltern Studies V111, New Delhi, Oxford University Press.

- Hemmings, Clare (2005) Invoking affect: cultural theory and the ontological turn. Cultural studies, 19 (5). pp. 548-567.

- John Jessup (1969). The Ideas of Henry Luce, Atheneum, New York.

- Life Magazine, 3 Nov 1947, Margaret Bourke-White’s The Great Migration: Five Million Indians Flee for Their Lives 117-125.

- Margrate Bourke White, available at http://www.gallerym.com/artist.cfm?ID=17, site accessed on 21 July 2012.

- Maren Stange (1992), Symbols of Ideal Life: Social Documentary Photography in America, 1890- 1950, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Michael Denning (1998). The Cultural Front The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century, London, Verso.

- Pandey, Gyanendra (1991), “In Defence of the Fragment: Writing about Hindu-Muslim Riots in India Today,” Economic and Political Weekly p. 559-572.

- Siscly, Ingrid (2003), “Between the Eyes” in David Levi Strauss, Essays on Photography and Politics, Aperture, New York, p.5.

- Stein, Sally (1992), “The Graphic Ordering of Desire: Modernization of a Middle Class Women’s Magazine 1919-1939” in Richard Bolton (edt) Contest of Meaning Critical Histories of Photography, MIT, Cambridge, p.145-161.

- Robert Vanderlan (2012). Intellectual Incorporated: Politics, Art, and Ideas inside Henry Luce’s Media Empire. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

- Wendy Kozol (1994). Life’s America: Family and Nation in Postwar Photojournalism, Temple University Press, Philadelphia.

- Misri, Deepti (2011), “The Violence of Memory: Renarrating Partition Violence in Shauna Singh Baldwin’s What the Body Remembers”, available at http://wgst.colorado.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/, site accessed on 22 July 2012.

- Tagg, John (2003), Melancholy Realism: Walker Evans’s Resistance to Meaning, available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/20107300, site accessed on 26 Oct 2011.

- Vials, Chris (2006), “The Popular Front in the American Century: “Life” Magazine, Margaret Bourke-White, and Consumer Realism, 1936-1941”, available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/20770947, site accessed on 3 Nov. 2011.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- From Militancy to Stone Pelting: The Vicissitudes of the Kashmiri Freedom Movement

- 75 Years Post-Independence, India’s Tryst with Fear

- Opinion – Pakistan Hatred Sells in Modi’s India

- Opinion – The Aam Aadmi Party’s Effect on Indian Politics

- Psychological Othering in South Asia: Root Causes and Pathways for an Enduring Solution

- Opinion – Opposition Strategy and Perspective in India’s 2024 Elections