Introduction

Article 45 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, governing the free movement of workers in the EU, has induced considerable debate on the outcome of this right on both the member state and the EU. The main question is whether free movement of labor will have a negative outcome for the participant countries, by causing lower wages and higher unemployment rates in the countries that receive migrants, exhaust sending countries of their much-needed human capital, or lead to a more competitive EU labor market that sees a higher economic growth rate. This paper will focus on underlying drivers of emigration from Estonia, using case-studies done on other Baltic and Eastern European countries because of their comparable communist past and analogous labor markets.[1] Based on the case-studies, the paper will explore whether emigration from Estonia has had a similar effect on the labor market like in other Eastern European countries of the EU.

Firstly, the overall characteristics of the Estonian demographics are presented. A relatively low birth rate, an ageing population and a negative net migration rate describe the country of 1.3 million people. These features are meant to exemplify the declining number of labor force which the future policies will have to take into account besides emigration. Secondly, the composition of Estonian migration and the characteristics of an average Estonian migrant are provided. Thirdly, it is argued that the share of highly-skilled labor in labor outflows has not been large enough to constitute a general “brain drain” in Estonia after the accession to EU. Fourthly, the migration barriers are discussed and it is argued that migration has actually become more open over time as the share of low-skilled migrants has been on the increase – proof that migration has become more egalitarian. Lastly, it is demonstrated that remittance flows to Estonia have been relatively large since 2004, and that despite of the significant loss of its working-age population to other EU member states, this has not considerably affected its domestic labor market.

The conclusions shall establish the main points that came out of the analysis and highlight policy implications for future action which are grounded both in the demographic reality and the emigration rate.

Background

The population decline in Estonia has been a problematic topic that has been raised both in the government and in public debates, as deaths are projected to outnumber births from 2015 onwards.[2] Estonia has already witnessed a 5% population decline in the last ten years – from 1.37 million in 2000 to 1.26 million in 2012 which for a large part has been at the expense of the working-age population,[3] although emigration is not the only factor that has caused the decline in population. I outline the issues in this part of the paper to illuminate the demographic trends in the context of the emigration issue but also to later develop policy implications.

The first among the pressing issues is a low birth rate. This should be, however, seen in a general EU context since while it is true that birth rates are generally quite low in Eastern European countries, the Estonian birth rate is not one of the lowest among EU member states (10.7 in 2010).[4] For instance, in 2010 it was the seventh highest with 11.8 live births per 1000 population as compared to, for example, 8.6 in Latvia, 10.8 in Lithuania and 9.0 in Hungary.[5]There are countries that experience considerably higher birth rates in the EU, such as Sweden (12.3) and Ireland (16.8), but this illustrates the fact that a low birth rate is not specifically an Estonian problem as many other European countries are going through a similar demographic phase.

The second problem is an ageing society. The median age in Estonia is 39.7 years, which compared to the median age of Europe as a whole (40.1) and EU states like Germany (44.3) and Sweden (40.7), can be considered relatively average or even low.[6] However, the share of older population is growing fast and Eurostat projects that the proportion of 55-64 year olds will increase from 17.8% in 2010 to 20.2% by 2025, which would mean that without any policy interference, Estonia’s demographics will be very similar to Western European countries in the future.[7]

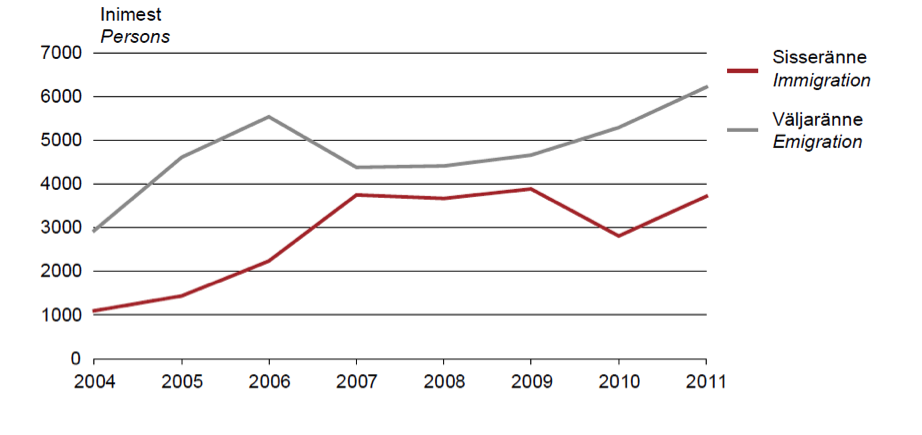

The third reason why the working-age population has been in decline in Estonia is a negative net migration rate. Emigration grew fast after accession to the European Union in 2004, it but stabilized by 2007, similar to the situation in other Eastern and Central European countries which experienced a similar surge after accession.[8] Outflow was the highest in those countries where per capita income was comparatively lower such as Slovakia and Poland.[9] While emigration has been on the increase after the economic crisis, so has immigration – although this is mainly attributed to returning migrants. Even though the labor force is returning now, the Estonian Ministry of Social Affairs has projected that the number of potential working-age emigrants, composed of individuals who express a clear desire to migrate and seek employment abroad in the future, can reach up to 77,000 people, constituting 8.5% of the entire working-age population.[10] This could almost equal the share of the work force that left other EU-8 countries and is worthy of comparison with case studies in other countries. A similar trend was observed in Lithuania where 9% of the work force emigrated to the UK and Ireland during 2004-2007.[11] In the case of Lithuania, emigration actually benefitted the people who did not decide to move. In the next parts of this paper I will see if the same is true for Estonia.

Estonian Emigration

Emigration from Estonia after the beginning of the economic crisis was primarily induced by lower wages, higher unemployment, a decline in job security and the lower chance of finding a job that was up to the worker’s expectations.[12] According to research done by Randveer and Rõõm in 2009, the typical Estonian emigrant in 2007 was male, 15-34 years old, a blue-collar worker and had most likely been previously working at a private sector enterprise.[13] This should not, however, be taken as a typical phenomenon throughout Estonian migration, as 2007 was an extraordinary year. Statistics Estonia has estimated that most migrants after the accession to EU in 2004 have been women and people with higher skills.[14] The most popular destination countries for Estonian emigrants in 2004-2007 were Finland, the United Kingdom, Ireland and Sweden.[15] Finland was most popular with an average annual migration rate of 2,449 persons, an outcome that can be attributed to the opening of the labor market to the Estonian work force in 2006.[16] Other factors that contributed favorably were a similar language and culture, and the pre-existence of a notable Estonian diaspora in Finland, making it easier for workers to move and settle there. In 2006 about 19,000 Estonians lived in Finland, a significant increase since 1990 when the community consisted only of 1,000 individuals.[17]

The UK, Ireland and Sweden were the second, third and fourth most preferred destinations for Estonian immigrants, mainly due to the fact that these countries were the first to open their labor markets for foreign workers after 2004.[18] Because of this these countries were also the most preferred by migrants from other Baltic countries.[19] Other member states such as Germany remained closed right after the accession and did not allow unrestricted access immediately to its labor market. For the UK and Ireland, language most likely played the most significant role in the choice of migration since English is relatively well know among Estonians, compared to other EU languages. As the Swedish language is not as typical among the Estonian labor force, emigration to Sweden was presumably motivated by other major factors such as geographical proximity and the relatively large wage difference. The per capita Gross National Income (PPP) in 2011 was $21,270 in Estonia, whereas in Sweden it was $42,350.[20]

The national census of 2011, reported that about 25,000 Estonian inhabitants currently work in other countries, constituting about 4.4% of the whole work force.[21] Based on projections made by Statistic Estonia, the Ministry of Social Affairs and Eurostat, it can be argued that Estonia will most likely remain a net emigration country in the coming decades with emigration greater than immigration. Moreover, it can be a considerable share of 8.5% of the working-age population that will move out to other EU member states in the next decades. The question remains whether this will have a positive or a negative effect on Estonian development, starting with the issue of barriers to migration, moving to the question of “brain drain” and finally to the effect of remittances.

Graph 1. Estonian emigration, immigration and net migration 2004-2011[22]

Have Barriers to Migration Increased or Decreased?

Firstly, I will analyze the issue if migration has become more or less egalitarian and whether it has allowed people with increasingly different skills to move from Estonia. Here one should consider that migrants need a considerable amount of capital for migration in order to travel, settle, and insure themselves against any possible risks. It is not always the poorest who migrate and the lack of a certain amount of resources can be a direct barrier to migration. Similarly the ones that usually migrate have already higher social capital than the average in the receiving country.[23] This was also the case in Estonia where emigration in the post-2004 period consisted of a large number of highly skilled people which, according to Randveer and Rõõm, was a sign that the poorest in the society did not have the resources to pay for migration.[24] This corresponds with the line of thought that highly skilled people also have on average more resources than low-skilled workers, causing a situation where the resource restriction for low-skilled workers is higher than for high-skilled workers since wealthier people with more human capital are better insured against future complications in the receiving country. The reality that economic problems are very likely to occur can be seen in the 2008 economic crisis. This was the case when the economic situation turned rapidly against newly arrived migrants.

However, it is important to note is that while a large share of all Baltic pre-accession migrants were predominantly highly educated workers, this decreased after the 2004 enlargement of the European Union.[25] Thus, the share of low-skilled Estonian migrants increased in the overall outflow. One explanation is that while previously low-skilled workers had high migration barriers since employers preferred high-skilled workers, this became less of a factor after Estonia’s accession to the EU allowed the free movement of any kind of workers. The right to migration extended to a wider share of Estonian population, evolving into a more equal process that affected people with more heterogeneous skills. Emigration from Estonia has thus become more egalitarian but, since generally it still consists of a large share of workers with higher skills, does this pose any structurally negative problems for the labor market such as “brain drain”?

Brain Drain

“Brain drain” occurs when a country loses a large part of its high-skilled work force due to emigration. Developing countries are known to suffer most from this as the large wage gap can cause emigration among well-educated citizens. This causes a decrease in the sending country’s human capital and its ability to develop as the labor market becomes considerably deprived. “Brain drain” has been associated with areas such as Africa and the Caribbean, where a large portion of the high-skilled labor force has migrated to either the US or Canada.

The effect of “brain drain” has been an issue of constant debate. According to authors like Kapur and McHale, the receiving countries are doing a disservice to less developed countries by trying to attract high-skilled labor, as this is detrimental for the labor markets and development of the sending countries.[26] With this line of thought, labor markets in less developed countries would become even more saturated with low-skilled labor – a hindrance to advancement. Other authors like claim that it does not actually play a large role if one would take the whole world into perspective. For instance, Hein de Haas points out that that in reality high-skilled labor makes up only a fraction of the total migration and so it is harmful only on certain occasions.[27] We must look at specific case-studies in order to understand whether “brain drain” has actually been taking place in Estonia.

Anniste, Tammaru et. al., while studying the migrants’ educational level, found that migration had not significantly changed the skill composition of the Estonian labor market and, moreover, had not caused a significant “brain drain”.[28] They concluded that while migration had significantly increased from 2004 onwards and Eastern European migrants were on average more educated than the local population in the receiving West-European country, the proportion of highly educated workers was lower among the migrants than in the total Estonian population.[29] This means that while the post-accession migration consisted of a large share of high-skilled workers, it was still less skilled, when compared to the total Estonian labor force. Therefore, we can conclude that, overall, when not taking into account specific labor sectors, “brain drain” did not seem to take place in Estonia. It might have specifically affected certain labor sectors such as healthcare but here the research is lacking. Moreover, any negative effects in these areas could be offset by the possibly positive effect on remittance inflows.

The Effect of Remittances in Estonia

Remittances are transfers of financial capital from emigrants in the receiving country to the people who stayed in the country of departure (sending country). They are seen as an effective way of counterbalancing any possible negative outcomes of migration and lower unemployment in the sending country. The effect of remittances has been found to be ambiguous by various authors in other regions outside of Europe, either by having no or even a negative effect on the economy of the home country.[30] Hence, it is important to focus on the situation in Estonia and find out what kind of an effect have remittances had on GDP growth and unemployment.

Hazans and Philip report that Estonian and Latvian migrants remitted back more money after the 2004-accession than Lithuanians – about 2-2.5% of the countries’ GDP.[31] While the authors themselves don’t consider this a significant share of the Estonian and Latvian economies, this should be compared to other Eastern European countries in order to put it into a better context. For example, a study conducted about remittance inflows to Eastern and Central European countries found that the remittances of Hungarian and Slovenian emigrants made up only 0.3% of the Hungarian GDP and 0.8-0.9% of the Slovenian GDP in 2006.[32] One has to be skeptical of these numbers as the remittance flow to Estonia may seem considerably larger than in the other countries but not all money transferred back home is done through official networks and to a large extent it is brought to the home country in person. Research done by the World Bank has different information from 2004, showing Hungarian remittances at 3.0-4.0% of GDP but still reaffirms that remittances to Baltic countries are larger per capita GDP than in places like Poland and Slovenia but smaller in less developed countries like Albania and Moldova.[33] This, however, does not mean that less developed countries always remit more but generally there seems to be a negative correlation between level of development and size of remittances. However, what was the effect on the labor market?

In a study conducted by León-Ledesma and Piracha in 2001, concerning the effects of remittances on the labor market of Central and Eeastern European countries, the authors note that remittances had a positive influence on the labor market of the sending country. Remittances reduced labor market constraints and opened up jobs in areas where competition used to be higher. Moreover, remittances were used by returning individuals to fund activities in their home country and not wasted on consumption.[34] The funds sent by those that had left the country promoted growth in productivity and had thus been a positive contribution to labor market of the sending state. One could suppose that, even though, the study did not specifically take into account Estonia, the same could be taking place there.

Remittances have improved the well-being of people in Estonia, as economic hardship has been lower among the share of those households that have family members in other countries.[35] This has, thus, helped to considerably alleviate economic problems during the crisis. Moreover, based on the evidence, it is possible to say that remittances have more likely improved rather than harmed the economic situation of individuals who did not migrate. The convergence of wages and a higher productivity rate are helping the EU-8 countries catch up with the living standards in the Western European countries. Despite the severe recession and Euro crisis, the Baltic countries of Latvia and Estonia have improved their position the most among the new member states.[36] Further catch-up of wages will in turn decrease the rate of migration considerably during the next decades since wage differences will become noticeably smaller.

Conclusions and Implications for Policy

Statistics have demonstrated that Estonia’s working-age population is declining and this is caused by a number of factors including a low birth rate, an ageing population and a negative net migration rate. As 8.5% of working-age population was projected to leave the country after joining EU in 2004, the effect of migration on domestic labor force is of crucial interest for the government. The emigration from Estonia was mostly caused by the wage difference between Estonia and the old European member states and the outflow of labor increased due to the freedom of movement that characterized the Estonian accession to the EU in 2004. Firstly, emigration from Estonia consisted mostly of high-skilled labor but this was followed by less-skilled workers alongside with the weakening of migration barriers, as well as the successive opening of the labor markets of the United Kingdom, Ireland, Sweden and Finland.

The literature confirms that the barriers to migration were reduced with time as the accession to the EU made migration comparatively easier for migrants. This was seen through the increase in the number of low-skilled workers after 2004, but which has still remained lower the share of high-skilled workers. Even though migration has primarily consisted of high-skilled workers, it hasn’t been causing “brain drain” as it structurally consists of a smaller share of high-skilled workers than in the total Estonian population. Migrants were on average more high-skilled but their share was not as high as in the labor market back home. On the part of remittances, it was found that they do play a role on the Estonian labor market and development by lowering unemployment through growth in productivity. Moreover, remittances had a positive effect on GDP growth, increasing the life standards of those who had decided to stay home.

To conclude, it has not been demonstrated that emigration has had a negative effect on the Estonian labor market or its economic development. Labor migration has even improved the living standards of those who stayed in Estonia and will continue to do so if it continues in a reasonable and decreasing manner. It will, additionally, continue as long as the large wage and development gap between Estonia and countries like Sweden, Finland, the UK and Ireland continue to persist.

Policy Implications:

- The loss of working-age population is a serious issue that needs tackling but it not so much related to emigration but also other trends such as a low birth rate and an older population play a role.

- Free movement of workers has to remain a fundamental right as stated in the Lisbon Treaty. Estonia should refrain from a protectionist approach toward migration that could lead to restrictions on emigration. The current emigration regime seems to function well, benefitting both the people that stay and those that leave.

- Free movement of workers, however, does not mean that the country cannot foster the return of migrants in certain sectors that are lacking in labor. Estonia should promote labor circulation and the return of skilled labor but in reality this can only happen when the wage gap with countries such as Finland, Sweden and the UK has narrowed sufficiently.

- Although not a directly related to the discussion in this paper, Estonia should also review the current immigration regime to make up for permanent labor force losses. The current immigration regime, based on Section 6(1) of the Aliens Acts states that “[…] the quota for aliens immigrating to Estonia […] shall not exceed 0.05 per cent of the permanent population of Estonia annually”.[37] This restricts immigration on a fixed number every year that may not compensate the annual labor force loss. This policy should be reviewed in the coming decades if Estonia wishes to have a sustainable labor force.

Bibliography

Anniste, K. Tammaru, T. Pungas, E. Paas. T. (2012) “Emigration after EU Enlargement: Was There a Brain Drain Effect in the Case of Estonia?” – University of Tartu Faculty of Economics & Business Administration Working Paper Series. Issue 86, pp. 3-20

Black R, Natali C, Skinner J (2005). “Migration and Inequality.“ Equity and Development. Background Paper for World Bank’s. World Development Report 2006

De Haas, H. (2005) „International Migration, Remittances and Development: myths and facts“. – Third World Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 8 (December), pp. 1243-1258

Elsner, B. (2012) “Does Emigration Benefit the Stayers? The EU Enlargement as a Natural Experiment: Evidence from Lithuania”. IZA Discussion Paper No. 6843.

Eurostat. (2011) „The 2012 Ageing Report: Underlying Assumptions and Projection Methodologies“. European Economy Series: 4/2011

FitzGerald, J. (2011) “To Convergence and Beyond? Human Capital, Economic Adjustment and a Return to Growth”. The Economic and Social Research Institute, Dublin. DG ECFIN Annual Research Conference, Brussels, pp. 3-25

Gianetti, M. Federici, D. Raitano, M. (2009) “Migrant Remittances and Inequality in Central-Eastern Europe”. – International Review of Applied Economics. Vol. 23 Issue 3, pp. 289-307

Hazans, M. Philips, K. (2008) “The Post-Enlargement Migration Experience in the Baltic Labor Market”. IZA Discussion Paper 5878, pp. 3-25

IOM. (2009) “International Migration Law No16 – Laws for Legal Immigration in the 27 EU Member States”. IOM and European Parliament

Kapur, D. Mchale, J. (2005) Chapter 1 of “Give Us Your Best and Brightest: The Global Hunt for Talent and Its Impact on the Developing World”. Center for Global Development

León-Ledesma, M. Piracha, M. (2001) “International Migration and the Role of Remittances in Eastern Europe,” Studies in Economics 0113, Department of Economics, University of Kent, pp. 1-14

Marcu, M. (2011) “Population Grows in Twenty EU Member States”. Eurostat Statistics in Focus: Population and Social Conditions. 38/2011

Mansoor, A. Quillin, B. (eds) (2007), “Migration and Remittances. Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union” (Washington DC: The World Bank)

Riigikogu Publications. http://www.riigikogu.ee/rito/index.php?id=11791&op=archive2, Accessed 1.12.12

Randveer, M. Rõõm, T. (2009) “Chapter 3. Volume of Recent Emigration from the EU-8 to the EU-15: Assessment on the Basis of Statistics from Receiving Countries”. – Working Papers of the Bank of Estonia, Issue 1, pp. 17-25

Randveer, M. Rõõm, T. (2009) “The Structure of Migration in Estonia: Survey-Based Evidence”. – Working Paper of the Bank of Estonia, Issue 1, pp. 7-46

Statistics Estonia. “Statistical Yearbook of Estonia”. Tallinn: July 2012

Statistics Estonia: Population and Housing Census. “25 000 Estonian Inhabitants work abroad”. Press Notice 19.12.12.

Tammaru, T. Kumer-Haukanõmm, K.. Anniste, K. (2010) “The Formation and Development of the Estonian Diaspora”. – Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. Vol. 36, No. 7, pp. 1157-1174

Veidemann, B. (2010) “The Emigration Potential of the Estonian working-age population in 2010”. Estonian Ministry of Social Affairs. Policy analysis Paper No. 8/2010

World Bank Data. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.PP.CD. Accessed: 19.12.12

[1] Elsner, B. (2012) “Does Emigration Benefit the Stayers? The EU Enlargement as a Natural Experiment: Evidence from Lithuania”. IZA Discussion Paper No. 6843.

Gianetti, M. Federici, D. Raitano, M. (2009) “Migrant Remittances and Inequality in Central-Eastern Europe”. – International Review of Applied Economics, Vol. 23 Issue 3, pp. 289-307

Mansoor, A. Quillin, B. (eds) (2007), “Migration and Remittances. Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union”(Washington DC: The World Bank), p. 59

[2] Europa Press Releases RAPID. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_STAT-08-119_en.htm. Reference: STAT/08/119 Event Date: 26/08/2008. Accessed: 17.12.12

[3] Statistics Estonia. http://www.stat.ee/34277. Accessed 17.12.12

[4]Marcu, M. “Population Grows in Twenty EU Member States”. Eurostat Statistics in Focus: Population and Social Conditions. 38/2011

[5] ESRI: Health Research and Information Department. “Perinatal Statistics Report 2010”.

[6] http://data.un.org/Data.aspx?q=median+age&d=PopDiv&f=variableID%3A41

[7] Eurostat. „The 2012 Ageing Report: Underlying Assumptions and Projection Methodologies“. European Economy Series: 4/2011

[8] Statistics Estonia. http://www.stat.ee/49474. Accessed: 16.12.12

[9] Randveer, M. Rõõm, T. (2009) “Chapter 3. Volume of Recent Emigration from the EU-8 to the EU-15: Assessment on the Basis of Statistics from Receiving Countries”. – Working Papers of Eesti Pank. 2009, Issue 1, p. 20

[10] Veidemann, B. (2010) “The Emigration Potential of the Estonian working-age population in 2010”. Estonian Ministry of Social Affairs. Policy analysis Paper No. 8/2010, p. 7

[11]Elsner, B. (2012) “Does Emigration Benefit the Stayers? The EU Enlargement as a Natural Experiment: Evidence from Lithuania”. IZA Discussion Paper No. 6843. September 2012

[12] Veidemann, B. (2010) “The Emigration Potential of the Estonian working-age population in 2010”. Estonian Ministry of Social Affairs. Policy analysis Paper No. 8/2010, p. 5

[13] Randveer, M. Rõõm, T. (2009) “The Structure of Migration in Estonia: Survey-Based Evidence”. Bank of Estonia. Working Paper Series, 1/2009, p. 2

[14] Statistics Estonia. (2012) “Statistical Yearbook of Estonia”. Tallinn, p. 53

[15] Randveer, M. Rõõm, T. (2009) “The Structure of Migration in Estonia: Survey-Based Evidence”. Bank of Estonia. Working Paper Series, 1/2009, p. 24

[16] Randveer, M. Rõõm, T. (2009) “Chapter 3. Volume of Recent Emigration from the EU-8 to the EU-15: Assessment on the Basis of Statistics from Receiving Countries”. – Working Papers of Eesti Pank, Issue 1, p. 24

[17] Tammaru, T. Kumer-Haukanõmm, K. Anniste, K. (2010) “The Formation and Development of the Estonian Diaspora”. – Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. Vol. 36, No. 7, pp. 1170

[18] Randveer, M. Rõõm, T. (2009) “Chapter 3. Volume of Recent Emigration from the EU-8 to the EU-15: Assessment on the Basis of Statistics from Receiving Countries”. – Working Papers of Eesti Pank. Issue 1, p. 21

[19] Hazans, M. Philips, K. (2008) “The Post-Enlargement Migration Experience in the Baltic Labor Market”. IZA Discussion Paper 5878, p. 3

[20]World Bank Data. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.PP.CD. Accessed: 19.12.12

[21]Statistics Estonia: Population and Housing Census. “25 000 Estonian Inhabitants work abroad”. Press Notice 19.12.12.

[22] Statistics Estonia. http://www.stat.ee/49474. Accessed: 17.12.12

[23]Randveer, M. Rõõm, T. (2009) “The Structure of Migration in Estonia: Survey-Based Evidence”. Bank of Estonia. Working Paper Series, 1/2009, p. 14

[24]Randveer, M. Rõõm, T. (2009) “The Structure of Migration in Estonia: Survey-Based Evidence”. Bank of Estonia. Working Paper Series, 1/2009,

[25] Hazans, M. Philips, K. (2008) “The Post-Enlargement Migration Experience in the Baltic Labor Market”. IZA Discussion Paper 5878, pp. 10-11

[26] Kapur, D. Mchale, J. (2005) Chapter 1 of “Give Us Your Best and Brightest: The Global Hunt for Talent and Its Impact on the Developing World”. Center for Global Development, p. 6

[27] De Haas, H. „International Migration, Remittances and Development: myths and facts“. – Third World Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 8 (December), p. 1247

[28] Anniste, K. Tammaru, T. Pungas, E. Paas. T. (2012) “Emigration after EU Enlargement: Was There a Brain Drain Effect in the Case of Estonia?” – University of Tartu Faculty of Economics & Business Administration Working Paper Series, Issue 86, p. 15

[29] Ibid. p. 12

[30] Black R, Natali C, Skinner J (2005). “Migration and Inequality.“ Equity and Development. Background Paper for World Bank’s. World Development Report 2006, p. 10

[31] Hazans, M. Philips, K. (2008) “The Post-Enlargement Migration Experience in the Baltic Labor Market”. IZA Discussion Paper 5878, p. 24

[32] Gianetti, M. Federici, D. Raitano, M. “Migrant Remittances and Inequality in Central-Eastern Europe”. – International Review of Applied Economics. May 2009, Vol. 23 Issue 3, pp. 292

[33] Mansoor, A. Quillin, B. (eds) (2007), “Migration and Remittances. Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union“(Washington DC: The World Bank), p. 59

[34] León-Ledesma, M. Piracha, M. (2008) “International Migration and the Role of Remittances in Eastern Europe,” Studies in Economics 0113, Department of Economics, University of Kent (2001), pp. 13

[35]Hazans, M. Philips, K. “The Post-Enlargement Migration Experience in the Baltic Labor Market”. IZA Discussion Paper 5878, p. 24

[36]FitzGerald, J. (2011) “To Convergence and Beyond?Human Capital, Economic Adjustment and a Return to Growth”. The Economic and Social Research Institute, Dublin. DG ECFIN Annual Research Conference, Brussels, 21st, p. 6

[37] IOM. “International Migration Law No16 – Laws for Legal Immigration in the 27 EU Member States”. IOM and European Parliament: 2009. p. 229

—

Written by: Lauri Peterson

Written at: Central European University

Written for: Martin Kahanec

Date written: January/2013

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Women in International Migration: Transnational Networking and the Global Labor Force

- Women’s Rights in North Korea: Reputational Defense or Labor Mobilization?

- Conceptualising Europe’s Market Power: EU Geostrategic Goals Through Economic Means

- Institutionalised and Ideological Racism in the French Labour Market

- How Does the EU Exercise Its Power Through Trade?

- The Crime-Conflict Nexus: Connecting Cause and Effect