Shadows from the Past: How Iron Curtain Despots Continue to Dictate Economic Performance in Slovenia, Poland, Romania and Albania

Abstract

When attempting to explain economic conditions in the former Eastern Bloc, analysts primarily take into account the present-day variables of a nation’s infrastructure, socio-geographic location and regulatory environment. However, relatively little attention has been paid to the pre-existing political conditions which were present in a nation under communism. This paper analyzes the policies of the communist dictators in Slovenia, Poland, Romania and Albania. It then compares these policies with post-communist economic indicators for these countries. This methodology shows that there is an inverse connection between the degree of totalitarian policy which existed in a nation under communism, and its economic performance since the fall of the Iron Curtain.

Introduction

Twenty-nine years ago my mother traveled to Poland as a journalist, to cover the country under martial law. She spent the Christmas vigil with a family in the infamous communist housing complex of Nowa Huta. I grew up hearing Nowa Huta essentially described as the epitome of all that was wrong in communist Poland. So, despite having been to Poland multiple times, it was not until last summer that I worked up the courage to take the tramwaj out to this section of Kraków. What I found there surprised me. I had heard up to that point Nowa Huta was still one of the poorest and ugliest parts of Kraków. Instead, I found a well-kept development, free of any obvious poverty. Compared to other block housing developments I have visited in Romania and Albania, the buildings in Nowa Huta were in good condition.

Despite this encouraging discovery, reminders of the country’s troubled past could be seen everywhere. It’s not that the scars of the socialist era have yet to heal; the development was originally conceived as a model socialist utopia, but the statue of Lenin which once dominated Nowa Huta’s Plac Centralny is conspicuously absent. It was replaced on the far end of the square by a monument to the Solidarity movement. A chapel has been consecrated on the site where the government’s refusal to allow the residents to build a church incited riots. The cross originally in the field is now a monument.

With these thoughts in my head I decided to stop at a café on the main square before heading back to central Kraków. Soon after I sat down, one of Nowa Huta’s senior citizens, a resident for more than 50 years, entered and asked if he could sit with me. We began talking about how the city had changed. “Everything works now,” he opined, “but these days we lack community.” He proceeded to tell me of late nights, organized by the socialist party, at the cinema, and of dancing until dawn in the city’s famous Restaracja Stylowa. “It was truly beautiful,” he added, “but young people these days are only interested in new things.” I was shocked. Although many Poles did at first support the socialist regime for rebuilding after years of economic mismanagement and Nazi occupation, they also quickly soured on the idea (Moja Nowa Huta, 2009). This was the first time I had ever heard Poland’s communist era described as anything but horrible in the modern day. At the same time, I also had to admit that the old man had a point. Essentially, he had just confirmed what I had been thinking. Poland’s most deplored communist housing estate had clearly been transformed, while never ceasing to be an obvious construct of socialist-realist thought. Yet, in other countries, similar rows of blocks more closely came to resemble a sort of Marxist-dystopian state of decay as their economies struggled after the fall of the iron curtain. Unlike most, the old man did not simply dismiss the nation’s socialist past as a 55 year-long mistake. He recognized it as a defining feature of the country’s present.

His simple comments summarize much about the current economic situation in central-eastern Europe. All of the countries existed under communist regimes two decades ago. However, some countries have made the post-communist transition more successfully than others. Poland and Slovenia have been two of the stars of the economic transition. Both countries are seen as an attractive environment for investment, and have enjoyed impressive economic growth. Other nations have not fared so well. Romania and Albania have struggled to institute a system of free enterprise, and to attract investment from foreign sources.

When analysts attempt to explain these differences in competitiveness, they often do so by examining a country’s infrastructure, socio-geographic location and current political and legal environment. These are all good measures: successful transition countries exhibit more desirable characteristics in each of these categories. However, relatively little attention has been paid to why a particular nation exhibits certain characteristics. The communist past of central-eastern Europe is often viewed as an obstacle which these nations must overcome. This is an oversimplified generalization. After the fall of communism, the differing policies of the various communist regimes made the economic playing field far from even. Their legacies remain as an inherent determinant of each country’s economic performance in the post-communist era. Therefore, in order to understand why one nation has the power to encourage growth and investment while another flounders, it is necessary to understand the current economic and political climate, as well as the policies of the former dictators which were the starting point for the evolution of the current business environment.

The aim of this paper is to show that there is a connection between the post-transition economic performance of a central-eastern European nation, and the past policies of the country’s former dictator. I will analyze the current state of the socio-geographic, political and infrastructure- oriented conditions in Slovenia, Poland, Romania and Albania, and compare it to political conditions under the previous communist regime in each country. This varied cross-section of post-transition economies will show the influence of policy under communism to give certain nations an edge in the competitive markets, while retarding the growth of others.

Literature Review

There have been many studies of economic and regulatory conditions in central-eastern European nations since the fall of communism. Many researchers take different approaches to explaining a nation’s success or difficulty in making the transition. While most of these writings center on the above-mentioned criteria, most of them prefer to focus on a single aspect of the transition such as the regulatory environment, or ease of transportation. Many of these writings mention what the situation was like before the early 1990’s, and discuss what happened since. However, relatively little attention has been paid to the reasons for these pre-existing conditions, and how they have influenced subsequent events. I will discuss some of the more revealing studies by country here:

Past Studies – Slovenia

As opposed to the slow pace of reform in other transition economies, Slovenia took quick action to distance itself from socialist Yugoslavia. Writings on this subject mention that some of Slovenia’s transition success was owed to its position within the larger socialist state. In Socio-economic Transition — The Slovenian Way, writer Carlos Silva makes clear that Slovenia’s subsequent success was initially a function of the former regime: “Slovenia embarked on its transition with some of the most favorable initial conditions of all the transition economies” (Silva, 2004, 130). He goes on to mention geographical location, composition of labor force, and policies that allowed the region to have trade agreements with the west under communism as some of these conditions. Because of this, he notes that the new country had less difficulty as the old eastern-bloc supply chains collapsed, than did many other transition nations which had depended on trade within the region of Soviet influence.

However, Slovenia’s position within Yugoslavia also was problematic when it declared independence. Silva also notes that the country’s financial situation as linked with the communist regime: “Slovenia inherited a large debt burden upon independence” (124). Quick action to address the problem was a key to overcoming this potential stumbling block. The conservative financial policies of the newly independent Slovenia were instrumental in gaining the trust of the international financial community.

Past Studies – Poland

In her Book “Privatizing Poland: Baby Food, Big Business and the Remaking of Labor” Elizabeth Dunn follows the case of one of the first plants to be privatized in Poland. This is one of the few works to undertake an in-depth description of how the business climate under a socialist regime directly influenced a country’s transition. In the beginning of her work she notes the importance of the socialist regime in defining Polish capitalism. “Polish workers spent more than forty years under socialism” she writes, adding that, “Their historical experience with socialism and the cultural system built and sustained during those years also allow them to contest, modify and reinterpret many initiatives of multinational corporations” (Dunn, 2004, 7). Dunn goes on to describe the resourcefulness of the Polish workforce, and the importance of personal connections in Polish culture. She argues that these abilities can trace their roots to Polish socialism and the martial law era, in which companies were required to meet quotas while operating in an environment of constant economic shortage; the plan relied on an adaptable system of small local suppliers.

At the same time, Dunn also points to Poland’s “shock therapy” approach to privatization as necessitating large amounts of foreign investment to succeed (35). Looking abroad for the necessary capital to start its capitalist experiment also meant that Poland and its companies had to quickly modernize regulatory and accounting systems (38-9). While the book does show the importance of pre-existing business conditions in determining post-communist success, it shies away from comparative analysis with other transition economies.

Past Studies – Albania

Other works provide more context of the transition through such comparison. One 1997 paper from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) shows how Poland’s regulatory environment allowed it to attract investment that the country needed to modernize. The report found, “The Polish Code of Administrative Proceedings has been amended … [according to] the general principles of administrative law and administrative justice which are widely recognized across Europe” (47). On the other hand, the report noted that seven years after the fall of communism Albania had yet to adopt a constitution; describing the current administrative and regulatory environment as “particularized and un-coordinated” (65, 68). The existence of a functioning administrative code, which could quickly be amended, allowed Poland to appear more secure to foreign investors. By comparison, the governmental disarray in Albania encouraged would-be investors to stay out of the market.

A 2010 OECD study reported that Albania continued to have trouble attracting investment; while Albania had made significant strides in setting up an administrative and regulatory system, improvements were still needed. Many key elements of a western business regulatory system had yet to be enacted. The report criticized the current legislative process, noting that the “government’s dialogue with stakeholders during the legislative and drafting process remains unstructured” (255). Thus, the still-volatile regulatory environment made doing business in Albania a risky prospect. For this reason, “attracting higher levels of direct foreign investment is still a challenge for Albania” placing it behind most of south-eastern Europe (251). The report placed the nation’s road system among the more developed in the Balkans. While Albania may currently be working to rectify is ailing regulatory and political systems, the country’s late start has put it at a disadvantage. However, no mention is made as to why the country came to be in this situation.

Past Studies – Romania

The same report also analyzed the current situation in Romania. While lauding the regulatory environment in most cases, the report pointed to “weak economic management” as hindering Romania’s ability to withstand the global economic crisis (OECD, 2010, 307). However, for much of the early 2000’s, domestic investment did fuel growth. The country’s large market size and inexpensive, educated labor force also made it attractive to foreign investment. The study pointed out the country’s poor road coverage and lack of railroad maintenance.

While this OECD report focused on Romania’s strengths, others have pointed to other factors that encourage companies to invest elsewhere. The United States Commercial Service branch in Bucharest has pointed to the lack of infrastructure, as well as a lack of government financial control, as mitigating factors in Romania’s growth. Existing roads are in poor condition and government attempts to rectify this by building highways have been held back by an inability to reliably budget and pay for construction projects from year to year (Kirkham, 2010). Although the OECD pointed to low, flat taxes as a positive influence in business development, it also noted the current inability of the government to increase the sophistication of its taxation system. The report states that the Ministry of Finance would like to implement a more comprehensive revenue scheme (OECD,2010, 310). However, according to the U.S. Commercial Service, the Romanian government lacks the fiscal infrastructure to implement a graduated or corporate tax scheme. Analysts at the U.S. embassy have attributed the inadequate nature of Romania’s government institutions to its past situation; one of the former communist leaders, Ion Iliescu, remained in power during the 1990’s and few real reforms were made until late in that decade.

These reports correctly point to physical location, infrastructure, and stable administrative climate as reason for economic success in Eastern Europe. A disadvantageous position in one of these factors can result in difficulties for a national economy. However, few reports even mention the pre-existing conditions which were created in the transition economies by their past communist regimes. Those that do mention them merely state what those conditions were, simply attributing them to ‘communism’. The main focus is on business policy decisions taken after the fall of the Berlin Wall. For this reason, there has been relatively little business-oriented analysis which links factors of present-day economic success, to the policies of past communist regimes. Many communist heads of state followed vastly different political and economic philosophies, albeit while fitting into the general framework of Marxist thought. Thus, the commonly taken short-term view of economic success in central eastern Europe can give one an incomplete picture of the underlying reasons for a nation’s current economic potential, or lack thereof. In order to gain a better understanding of the factors influencing a country’s potential, it is necessary to understand where it came from.

The Political History

Under communism, all eastern bloc nations were governed by a single party system. The communist or socialist party denominated government; its most powerful member or members were usually the head of state. Despite these apparent similarities, the commonly made assumption that communism was an equally adverse monolith in all of these countries is false. In the four countries which this paper examines the range of dictatorial policy is staggering. Some of these regimes followed relatively market-oriented paths, while others attempted to plan the entire economy. Some opened their borders to trade and ideas, while others isolated their people. Some heads of government used power sparingly, while other dictators ruled with an iron fist, squashing all opposition to their personal vision of a socialist utopia. Because of this the seeds of capitalist revolution were planted long before the transition period in some economies, and much after in others.

Due to the wide variance in how socialist heads of state attempted to implement their visions, it is difficult to quantify any one of their philosophies as the determinant of economic performance in the current era. However, it can be said that the degree to which they implemented these philosophies through acts of open despotism carries long lasting post-transition implications.

In many cases these differences can trace their roots back to the post-war period, including the de-Stalinization of the early 1950’s, and resulting relations with the Soviet Union. After Stalin’s death, the Soviet Union proclaimed a shift away from militant Stalinist policies. However, not all nations moved in lock step with the USSR as the process got underway. The result was the creation of different interpretations of Marxist rhetoric in different nations. This concept termed by McDermott & Stibbe as “national communism” could be carried out by a government either by distancing itself from the Soviet Union and its policies or by simply by negotiating for political autonomy in domestic policy from Moscow’s party line (2006, 4). “The foremost representative of the first variant was Tito,” they write of Yugoslavia’s president- for-life, citing his relative openness to the West and international community. Albania under Hoxha and Romania under Ceauşescu also openly rejected the Kremlin, while retaining many facets of Stalinist thought. Poland, under Gomułka and later Jaruzelski, represented an example of the purely domestic variety of communist differentiation. This allowed the country to make limited market-oriented reforms, without inviting military invasion from Russia or the Warsaw Pact. These two schools of nationalized communist ideology do not by themselves provide much insight into economic performance, but they are an effective context for discussion of individual political and economic legacies that resulted from this ideological split.

Tito

In Yugoslavia, this split from unified communist ideology began while Stalin was still alive. The country was the first to break from the Soviet party line in the late 1940’s. While relations between Stalin and Tito were originally amicable, they showed increasing differences over Yugoslav interests in south-eastern Europe, including support of the Greek communist rebellion and the national status of Albania. Eventually, Tito simply began “to take decisive steps without prior authorization from the Kremlin” (Gibianskii, 2006, 30). Stalin officially sanctioned him for this behavior, accusing him of “revision of the most important Marxist-Leninist theses” (27). Afterwards, Tito took Yugoslavia in a new ideological direction.

As leader of a breakaway communist nation, Tito realized that he would have to forge other international alliances in order remain successful without the support of the powerful Soviet Union. For this reason many of his duties revolved around personal visits to many foreign heads of state. The Marshall did not confine his visits to other Eastern-bloc nations, but instead worked to create ties with a broad array of governments, including state visits to five different U.S. presidents (Museum of Yugoslav History, 2011). This relatively liberal diplomatic policy carried over into Yugoslav trade policy as well. As previously noted, trade ties with the west were also encouraged, and the government often did business with western banks and organizations. This open international policy allowed Slovenia some experience with western business practices, and pre-existing access to western distribution channels. As one of Yugoslavia’s economic powerhouses, Slovenia and its people were better prepared than other former communist nations to make the transition smoothly, as a result of Tito’s foreign policy.

Unlike some other communist states, centralized government control of the economy in Yugoslavia was also relatively weak. Local market economies functioned, while investment funds remained state-controlled. Biographer Geoffrey Swain writes that in Tito’s view, “the ‘state-administrative’ approach to running the economy was flawed by contradictions” (2011, 140). He adds that the Marshall supported greater local oversight of investment and production decisions (141). Despite his great power, the Yugoslav president-for-life did not demand complete control over the economy; instead he seemed content to let local officials handle those decisions, as long as they did so in a somewhat socialist manner.

Despite this, one of the main Slovene complaints against the national Yugoslav government continued to be the unfair distribution of funds to some of the poorer Yugoslav republics. The reforms to the national funds distribution system had only made this problem worse; essentially making it a matter of competition between Yugoslavia’s already contentious member republics. Swain notes in one 1969 incident, the Slovenes threatened to secede from Yugoslavia, over the redistribution of highway construction funding (Swain, 2006, 167-8). Instead of simply removing the Slovene officials from power Tito took the time to assuage their concerns.

From this point on, ethnic and national tensions in Yugoslavia would continue to grow. For much of his tenure, the Marshall instituted a strict policy of denationalization, in which nationalist sentiments were strictly forbidden. Tito often made use of his own propaganda image to focus attention on Yugoslav unity through his personality cult (Museum of Yugoslav History, 2011). After his death in the 1980’s, the political and ethnic climate deteriorated even more rapidly. As fighting broke out in other sections of the former nation, Slovenia relatively peacefully declared independence in 1992 without great political or economic hurdles to overcome.

Hoxha

Albania stands in stark contrast to Slovenia’s communist and post-communist experience. In many respects the two countries are very much alike. Both have roughly the same populations; each shares a favorable location between the other Balkan states and a long standing member of the EU. However, while Slovenia can be considered a transition success story, the Albanian economy continues to struggle to attract investment. The two nations also exhibit major differences insofar as the policies they were subjected to under communism.

Envir Hoxha, Albania’s dictator, was in many ways a mirror image of Yugoslavia’s leader. Whereas Tito broke with the Soviet establishment in order to pursue his own policies, Hoxha’s brand of Albanian national communism retained many Stalinist principals. The Albanian dictator considered Tito to be one of his archenemies, because of Yugoslavia’s break with Stalinist Moscow. Hoxha eventually broke with Soviet policy, but not until Khrushchev’s installment and de-Stalinization. Whereas most of the Soviet bloc regarded Stalinism as a departure from Marxism-Leninism, Hoxha regarded Stalin’s beliefs as a “further development of Marx, Engels and Lenin” or communism in its purest form (Hoxha, in Turku, 2009, 83). After Stalin’s death, Hoxha resolved on behalf of all Albanians to build upon his policies. Soon after coming to power, Hoxha moved to consolidate his power over Albania, putting to death all political and intellectual opponents. His goal was to shape Albanian communism by doing little more than issuing proclamations. The result was a state in which government was embodied by the infallibility of its leader in all matters.

Not only did the Albanian leader disallow any other decision making authority, the highly state-regulated domestic policies he implemented served to retard the functioning of the economy at any level. The Albanian Constitution of 1976 declared Hoxha as the sole guardian of the proletariat’s interests (Turku, 2009, 86). Whereas the market was allowed to function on a local level in Yugoslavia, Regulation was so severe in Albania that private property of any kind was essentially illegal (88). Local land and water use was determined by the government (De Waal, 2005, 75). Any hope of resistance to his brutal regime could not formed in churches or mosques. The 1976 constitution outlawed all religion in Albania, and a ruthless campaign was set up to eradicate its existence in the country. In this way, any institution in Albania that could foment any type of capitalistic practices or dissent was extinguished from existence. After Hoxha’s death, Albanians had no leadership capable of leading them into a new era. They also had no experience with anything but Hoxha’s policies of extreme central planning – policies that often had more to do with ideological paranoia, rather than making sure the proletariat had food to eat.

Whereas Tito was aware that success as a socialist breakaway nation was dependent on forming international alliances, Hoxha was obsessed with preserving Albanian independence. He refused to have any dealings with nations that did not share his political views. The problem was that no other nations shared them. After breaking ties with the USSR and withdrawing from the Warsaw Pact, Hoxha moved to forge an alliance with the People’s Republic of China, the only ally of Hoxha’s otherwise isolationist regime. After Chairman Mao’s death in 1976, China moved toward capitalist reform. In that same year the new Albanian constitution declared “self-reliance” as national policy, and banned all credit, aid or investment from foreign counties (Turku, 2009, 86). Two years later, Hoxha condemned Maoism and broke off all ties with China, leaving Albania completely isolated.

Hoxha was also notorious for mistrusting the West. Left alone, the dictator became convinced that his regime would be brought down by other regimes. For this reason he directed large sums of the country’s limited output toward building a network of thousands of concrete bunkers for defense purposes (Turku, 2009, 88). It was during this time that the country’s only rail lines, covering roughly 600 kilometers, were built (World Bank, 2012). However, lack of funds kept Albania from developing a highway system or reliable utilities. At the time of Hoxha’s death the country was left with limited resources, and no readily available sources of foreign aid. Of the entire population, only the former communist elite, who held onto power after Hoxha’s death in 1985, had any real contact with capitalism and foreigners (De Waal, 2005, 29). Only the elite were in any position to start enterprises after the fall of communism in 1991 (34). Ironically, Hoxha’s policies prevented the masses he claimed to represent from being able to function in the post-communist era of globalization.

It is clear that that Hoxha’s obsession with ideological purity compelled him to seek and wield absolute power over Albania. Both Tito and Hoxha broke with the Soviet Union, but they responded to non-alignment in fundamentally different ways. Tito’s decision to wield mild control over local government, pursue aggressive foreign policy and maintain a relatively open policy toward other nations prepared Slovenia to make the economic transition smoothly. On the other hand, as Turku writes, “Hoxha created one of the most isolationist states, domestically and internationally, in the annals of history” (2009, 89). The extent to which he choose to control every aspect of Albanian life for his own purposes caused Albania to struggle for direction through the 1990’s as it attempted to modernize its outdated ways overnight.

Ceauşescu

While Hoxha used his totalitarian power to lead Albania down a path of isolationism, lack of foreign or western ties cannot be considered a universal determinant in the level of difficulty a country has in creating a stable business environment during its post-communist transition. It is clear that Albania would have been better off if it had remained involved on the international stage. Yet, the country’s isolation is merely a symptom of the iron-fisted manner in which the First Secretary of the Albanian Party of Labor ruled. Romania has fared worse than other post-communist nations in encouraging investment or growing the economy in a stable manner. However, it was one of the eastern bloc’s foremost trading nations during the cold war. Much of this economic policy was implemented by the country’s most infamous dictator, Nicolae Ceauşescu. Despite the apparent differences in the policies themselves, the governing stiles of these two dictators bare striking similarities.

From the time they came to power both dictators single-mindedly believed in their own interpretations of Marxist theory. Each man also was convinced that he was the only one who could make his theory a reality. Ceauşescu broke from lockstep with the USSR soon after coming to power by condemning the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia during the 1968 Prague Spring. Like Hoxha, he also swiftly moved to consolidate his power after becoming general secretary of the Romanian communist party. This was done both through manipulating party policy in order to increase his power, and through the use of his secret police force, the Securitate. While religion was allowed in communist Romania, the Romanian Orthodox Church was state-controlled. (Deletant, 2006, 81). This had the effect of making resistance more difficult. Ceauşescu’s control over the government was so complete that, as Roper writes, the country’s political elite could be “narrowly defined by the end of the 1980’s as Ceauşescu’s family” (57). The Secretary General was heavily influenced by North Korean socialist thought, especially when it came creating his manner of governing. One of its main tenants was “dynastic socialism,” the idea that only Ceauşescu and his family could lift up the masses (51). To that end, he took to proclaiming all of his actions as leader ‘Ceauşescuism,’ a new brand of communism. Interestingly enough, the dictator’s notorious megalomania did not come from depravity or simply vanity; he truly believed the public would revere him for what he considered to be actions on their behalf (Palace of Parliament, 2010). This lead to a dangerous disconnect between his vision and the reality of life on the street for the average Romanian.

Under Ceauşescu, Romania pursued an aggressive trade policy. After his break with the USSR, the Secretary General looked to the west for financing; Romania joined GATT and the WTO as well as a number of other Western trade agreements (Roper, 2000, 52). It was also the first eastern bloc nation to receive MFN trade status. Romania also turned toward developing nations for trade. This allowed for the import of necessary raw materials to Romania, while avoiding the need for the machinery it exported to meet high quality standards (53).

Viewed from abroad, it appeared as if Romania was prospering under Ceauşescu. At home, the dictator implemented economic policy which can best be described as simplistic and lackadaisical. In order to finance economic growth and export he instituted a series of five-year plans designed only to increase industrial production. In order to comply with Ceauşescu’s demands, the bureaucracy was forced to sharply decrease the production of consumer goods, food and infrastructure; the standard of living in Romania actually decreased during the 1970’s despite its success abroad (Roper, 2000, 53). Eventually, as the country’s import needs exceeded its export capabilities, Romania could no longer finance growth and was faced with mounting debt.

Instead of diverting resources from industrial growth to pay down the debt, Ceauşescu ceased importing and began exporting consumer and agricultural products as well. With the country’s domestic resources already strained, this one-dimensional policy resulted in crippling shortages of foodstuffs and commodities for the Romanian people. Even worse, the dictator’s determination to continue industrial production without petroleum imports required that the country make use of whatever resources it had, such as brown coal, which resulted in the country’s infamous levels of pollution (Roper, 2000 55). During this time, Ceauşescu and his wife Elena publicly continued a plethora of costly projects.

The general secretary’s actions consistently evidence a rather literal or simplistic understanding of not only of economics, but also of communist rhetoric. During the height of his painful austerity program the dictator decided to show the power of the Romanian people by literally building a worker’s paradise. The result was the House of the Republic, the second largest building in the world, and its surrounding district. Ceauşescu ordered the destruction of much of Bucharest’s most historic district and the forced relocation of its inhabitants in order to build it. The dictator seemed completely unaware that his actions did not have the intended effect of glorifying his leadership. As Roper puts it: “Unfortunately he believed his own propaganda” (2000, 53). Guides on the author’s personal visit to Ceauşescu’s creation, today renamed the Palace of Parliament, insist that the dictator was not evil, but simply uneducated. Indeed, the near-absolute ruler of Romania could never have received more than an elementary school education. Despite the consequences of Ceauşescu’s overzealous debt reduction plan, it ironically achieved its intended purpose. After the dictator was removed from power in 1989 the country was left in a better financial position than many other transition economies. Taken by itself, this would appear to point to a stable Romanian economy in the present day. However, this is not the case. Ceauşescu’s ruthless insistence on absolute rule meant that there was no capitalist opposition to take over after he was removed from power. The Romanian dictator was the only leader of an eastern bloc nation to refuse to step down from power voluntarily. After his death there was no one to fill the vacuum of power, except other members of the communist party who had been sidelined to make way for Ceauşescu. One of these men, Ion Iliescu, took the opportunity to seize power. He was not voted from office until 2004.

To this day, there is a great deal of debate in Romania and abroad as to whether the post-communist transition began with the deposition of Ceauşescu. A majority of Romanians do not believe that the so-called 1989 revolution was actually a revolution (Roper, 2000, 60). Instead many think it was simply a coup in the communist party. Romanians did not vote in a free election until 1996, by which point the country has fallen behind many other transition economies including Poland (65).

While many other post-communist nations took legitimate steps to modernize in the early 1990’s, Bucharest implemented few reforms. Those reforms that were enacted seemed chiefly aimed at creating the appearance of a market economy, while maintaining government control over the factors of production. Although privatization of industry was legalized, it was not made practical nor sponsored by the government. For much of the 1990’s, the country had one of the lowest levels of FDI in all of Eastern Europe (Roper, 2000, 92). As under the Ceauşescu regime, policy continued to be economically unsound, with disastrous results. The establishment continued to follow the export-dominated strategy that had existed under Ceauşescu as a means of paying down debt for much of this time (93). As in Slovenia, Romania’s existing trade ties with a wide variety of nations allowed it to easily re-direct its flow of exports, although not with equal success. However, amid continued shortages, and without a great amount of privatized production at home, Iliescu’s government moved toward price liberalization and allowed the currency to float (89). The result was hyperinflation, which reached practically 300% in 1993 (96). Even the governor of the Bank of Romania, while defending government policy, was forced to admit that Polish style shock therapy “could have been the most beneficial model” (88). Although Romania was well placed to make the transition in 1989, by the time of the 1996 elections the complete lack of reform-oriented opposition ensured that Romania would fall seven years behind similar countries in the region, such as Poland.

Gomułka and Jaruzelski

In comparison to the near-complete absolute power exercised by the regimes of Hoxha and Ceauşescu, the Polish leaders Władysław Gomułka, and later on Wojciech Jaruzelski, represent two of the more open regimes in the former Iron Curtain countries. Although not as liberal in their policies as Tito, the Polish leaders sought to create their own brand of national communism, not by breaking with the USSR but instead by remaining in lock step with Moscow on the world stage, while implementing only those reforms at home that would go unchallenged by Soviet leadership.

After Stalin’s death, Poland, under Gomułka, led the way in destalinization. Especially in Poland, this took form in the creation of “socialist consumerism,” the objective of which was to provide for the satisfaction of consumer demand, while still maintaining government control over the major production factors (Mc Dermont and Stibe, 2006, 2). The Polish leadership also took steps to gain concessions for reform from the Soviet establishment, while making sure that reform did not go so far as to precipitate military intervention by Moscow. In one of the most important examples of this strategy, Gomułka used Poland’s international identification with the Soviet camp to gain permission from the Kremlin for “private landholding and the granting of considerable freedoms to the Catholic Church in Polish society” (Pearson in Mc Dermont and Stibe, 2006, 4). In future decades, these freedoms of the Polish Catholic church, including freedom from censorship, would play a pivotal role in the organization of the Solidarity movement’s resistance to the communist regime. Until the fall of the Berlin Wall, Polish leadership continued to pursue a policy of pushing just as far as Moscow would allow without inviting military invasion and the abolishment of reform, such as happened in Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968.

Gomułka’s successor, Jaruzelski, continued this policy, although he is often regarded in a much less favorable light. Major Solidarity protests had been taken place in the country for a decade by the time he become prime minister of the RPL in February of 1981. The Solidarity movement was gaining great prominence at the time. As one New York Times article described Russo-Polish relations of the time: “Even many Western defense planners believed a new Soviet military intervention was in the works” (Unger, 1993). Before this could occur, the General made the now-infamous decision to declare martial law in the country. Many Solidarity leaders were imprisoned as a result of the crackdown and the movement was forced underground. However, martial law held off a possible Soviet invasion, which had previously resulted in the abolition of opposition to reform in countries where it took place (Mc Dermont and Stibe, 2006, 4). In Poland under martial law, Solidarność continued to hold meetings in churches, unmolested by authorities (Anzur, 1983). While flower crosses were forbidden in prominent public areas, they were often allowed to flourish in less frequented parts of the city. The movement continued to survive as the country transitioned to democracy and capitalism.

In addition, after martial law was lifted two years later, the General made no move to halt reform. He voluntarily released power over the military and police, and allowed emptying the nation’s institutions of communists (Engleberg, 1990). In 1989 he voluntarily restored Solidarity’s legal status, and allowed it to gain political power. While Jaruzelski was still president, Poland “became the first non-Communist state in Eastern Europe since World War II” (Unger, 1993). Martial law was clearly anything but a boon to Poland and to its people. Any form of sympathy for the General is far from universally shared. Jaruzieski’s top advisors were declared a “criminal group” recently by a Polish court, albeit while receiving lenient sentences (Kulish, 2012). Jaruzelski himself has been declared medically unfit to stand trial. Despite the hardships Poland suffered as a result of Jaruzelski’s tenure, the alternative — Soviet invasion — could have been much worse for the country in the long run. As the new Polish democracy smoothly took form in the early 1990’s, Henryk Wujec, a Solidarity member of the Sejm spoke of the General as follows: “In the Communist camp, he was a pioneer of social compromise between the society and the Communist authorities. He was sober enough to realize that martial law did not work out very well and he tried to find a compromise solution” (Engleberg, 1990). In contrast to Ceauşescu’s zeal for snuffing out all opposition and willful refusal to step from power, Jaruzelski’s actions in the late 1980’s allowed Poland to make a smooth and successful transition to capitalism.

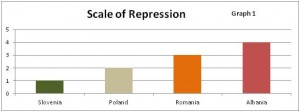

From the above discussion, it is clear that each of these dictators displayed wide variations in their specific views and policies. However a common determinant of future economic success runs through each of their regimes. The degree which to a given leader exercised absolute control over his country’s economy and its people directly can influence those factors which are commonly said to make a nation an attractive place to invest. Each of the regimes which this paper examines displayed differing levels of this trait. Tito’s relatively open policies toward trade and encouragement of local government and a limited marketplace make him the least repressive. The Polish regime would follow Yugoslavia in terms of relative oppression (see graph 1). While successfully avoiding Brezhnev-era Soviet military repression, this meant that Polish reform could only go so far during the Cold War. In addition, the martial law era does serve as a manifestation of absolute control, and thus as a barrier to Polish reform, regardless of the circumstances that surrounded it. That said, this period spanned a short time in the existence of communist Poland. These two countries display the least amounts of repression on the parts of their leaders. They also are two success stories of the post-communist transition.

While repressive at home, Ceauşescu’s aggressive, if single minded, trade policies did afford the country some contact with the west. These policies also had detrimental domestic effects. Any positives the Secretary General’s trade policies might have had were erased by the total lack of opposition outside of the communist party after Ceauşescu’s deposition. Thus, the dictator’s insistence on absolute control in Romania severely retarded the country’s prospects for growth, and arguably delayed any transition for 7 more years. This regime therefore falls into the second most repressive category on a scale of 4 to 1 (see Graph 1). Hoxha’s completely isolationist regime displays the most traits absolute control over all aspects of economy and expression in the country. This dictator not only ruthlessly quashed all political opposition to his rule, but also abolished all international trade– even trade with other communist nations— in order to make his control completely unfettered. Because of this, Albania had to overcome the apparent lack of a transition government, and also was faced with the prospect of relearning the basics of international trade. Thus, this regime can be considered as having the most repressive leader of the four transition nations examined by this paper. These two countries are also having more difficulty making the transition.

The Economic Data

At this point, the commonly used determinants of socio-geographic location, infrastructure development, and the current regulatory environment become of use. The countries with more benign communist dictatorships, Slovenia and Poland, exhibit higher amounts of infrastructure and a more stable governmental situation. Therefore they should also have higher relative levels of growth and investment. Romania and Albania on the other hand, should manifest less desirable amounts of each. Although the geographical location of a country cannot be directly influenced by dictatorial policy, it can be thought of as pre-existing condition, which comes into play when different countries were subject to similar regimes. This is most visible in the case of various former Yugoslav nations including Slovenia. A verification of this model for economic growth can be done by comparing infrastructure levels, namely amounts of paved road and rail, and existence of trade-bolstering institutions, especially export-import banks, in each country. Subsequently, the amounts of Real GDP growth and FDI present in each country since the effective fall of communism should be examined. This date varies from country to country. However, this study will use 1992, the year in which Slovenia declared independence, as the first relevant year. This date is the most representative of the sample nations, from the two extremes of Poland in 1989 and Romania in 1996. The case of each nation, by each criterion, will be discussed in the following pages.

Infrastructure

Slovenia does indeed claim the highest overall level of general infrastructure. As can be seen in the charts, Slovenia does boast the highest rate of infrastructure development in any of the sample countries. Much of this was due to road construction after the country declared independence in 1992, bringing the percentage of paved roads in the country from 75% to 100% (See Charts 2 and 3).

|

Infrastructure 1992 |

Chart 2 |

|||

|

Slovenia |

Poland |

Romania |

Albania |

|

|

Total Land Area (sq.km) |

20,140 |

304,420 |

229,460 |

27,400 |

|

Rail lines (total km) |

1,201 |

23,399 |

11,430 |

674 |

|

Rail Lines/ Total Land Area |

.060 |

.077 |

.050 |

.024 |

|

Proportion Paved road |

75.0% |

64.1% |

51.0% |

39.0%* |

*1995 data (1992-4 data not reported) Source: World Bank

|

Infrastructure 2008 |

Chart 3 |

|||

|

Slovenia |

Poland |

Romania |

Albania |

|

|

Total Land Area |

20,140 |

304,220 |

229,900 |

27,400 |

|

Rail Lines (total km) |

1,228 |

19,627 |

10,784 |

423 |

|

Rail Lines/ Total Land Area |

.061 |

.065 |

.047 |

.015 |

| Percent change from 1992 |

1.6% |

-15.6% |

-6.0% |

-37.5% |

|

Proportion Paved Road |

100.0% |

68.2% |

30.2%** |

39.0%* |

|

Percent Change from 1992 |

33.3% |

6.5% |

-40.8% |

0.0% |

|

Net total % Change from 1992 |

34.9% |

-9.1% |

-46.8% |

-37.5% |

*2002 data (subsequent data not reported) **2004 data (subsequent data not reported

Slovenia also displayed a healthy base level of transport related infrastructure when it split from Yugoslavia. Although Poland did register slight negative development of infrastructure since 1992, the country displayed the highest base level of rail, and continued to have the most rail lines relative to its size of any of the countries (See chart 3). Despite negative infrastructure development, Poland still had much more overall infrastructure than Romania or Albania. In both economies which were tightly controlled by dictators, infrastructure development was heavily negative where figures were even reported. This neglect of infrastructure reflects the difficulty which these countries had while trying making the economic transition. This trend is most noticeable in Romania. In 1992 Romanian infrastructure appeared to be in a relatively developed state. Transport-related infrastructure would have been necessary to facilitate Ceauşescu’s aggressive industrial production and export policy. The percentage of roads held steady as these policies were continued through 1996 (World Bank, 2012). However, as reform was finally implemented amid continuing financial problems the percentage fell through the early 2000’s. It should be noted that from 2002 to 2003 the amount of roads in Romania fell by exactly 50%, indicating a possible change in statistical practices. In Albania the amount of pavement held constant at a mere 39%, while the government was unable to maintain roughly a third of what rail lines it had.

The amount and development of infrastructure present in each country during this period mirrors the repressiveness of each country’s communist regime. Slovenia, which existed under the most benign socialist regime, displays universally positive figures. Poland continues to be in an overall favorable position, albeit while letting a small amount of their modes of transport fall into disrepair. The transition turbulence caused by the Romanian dictator’s absolute control resulted in widespread degradation of infrastructure after his death. Albania began the early 1990’s with low levels of infrastructure and then moved in the wrong direction (See charts 2 and 3).

Regulatory Environment

The regulatory environment in each of the nations exhibits a similar trend. As previously mentioned Poland’s legal framework and governmentally proactive approach to privatization did indeed make the country an attractive place to invest (Dunn, 2004). These policies either already existed, or were easily implemented when Jaruzelski handed power to the opposition. Although the Polish electorate’s traditional failure to elect the same coalition to power twice since the fall of communism was seen as source of uncertainty, this has conceivably changed with the re-lection of Prime Minister Donald Tusk to office last year (Dempsey and Kulish, 2011). A similar situation existed in Slovenia, where Tito’s policies allowed the existence of a semi-western system in Yugoslavia. Such pre-existing conditions were non-existent in the two other economies. In Romania, The effective lack of privatization, brought on by the lack of a reform government, retarded the country’s development prospects by at least 7 years when compared with most other transition economies. Furthermore, Ceauşescu’s tight control of the country’s economic policy made it more difficult for the government to gain knowledge of how to successfully execute any form of market-based fiscal policy. This communist-era lack of sophisticated economic policy may be the underlying reason for the continued “weak financial management” which OECD cites the Romanian government for in the present day. In Albania the lack of organized opposition led to political turbulence, resulting in an uncertain regulatory environment. Because of Hoxha’s extreme doctrine of isolationism, only the communist elite had enough contact with western ideals to be able to start any form of enterprise.

The advantageous position in which the Polish and Slovenian governments found themselves in from the beginning of their economic transitions allowed them not only to create a stable environment for investment, but also to encourage it by creating a stable environment for trade. Both of these countries have successfully functioning export-credit banks. These banks insure against a variety of trade related risks. This export credit insurance can encourage trade with more developed nations, through insuring the performance of the contractual member in the home country. As a country develops it can also be used to encourage trade growth by ensuring the performance of foreign parties in lesser developed nations. Of the nations in question, Poland, Slovenia and Romania have Exim banks. All three are members of the Prague Club, an alliance of export credit institutions dedicated to promoting trade in the former eastern bloc, and other developing economies (Berne Union, 2012).

Poland’s Exim bank, Kuke S.A. uses bank guarantees backed by the Polish national treasury to perform both of these functions. IT’s most recent annual report shows that the bank currently does over 30% of its business with Germany, the Netherlands and other western European economies alone (Raport Roczny, 2010, 8). The bank is also making strides promoting Polish industry in other transition economies, which have not been so successful. This group is mainly comprised of Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and Romania, representing roughly 26% of total contracts. Interestingly enough, the report notes fast- growing interest in this sector for treasury-backed export and bank guarantees related to the countries of Bosnia & Herzegovina, and Albania (14).

Slovenia’s bank performs a similar function by working with the Balkan economies, whose transition has been marked by ethnic tensions and civil war. The company has 100% owned subsidiaries in six Balkan countries including Romania (Financial Statements, 2010). The Romanian Exim bank itself seems to be mostly focused on providing loans to Romanians “so as to increase the technological level and heighten the competitiveness and quality of services and products delivered by them” (Eximbank Romania, 2012). This shows that the country still must focus on developing its own market before it can pursue a strategy of growth in other markets that need to develop. Tellingly, Albania does not have an Exim bank.

Again, the existence and activity of the export-import banks in each country closely follows the success it has had in making the transition. However, it should be noted at this point that Slovenia and Poland owe at least some of their growth through trade promotion to their favorable socio-geographic factors. Slovenia can use its position as a stable former Yugoslav society located between Italy, Austria and the Balkans in order to serve as a gateway for western companies wishing to enter those markets. This somewhat overcomes its small market size as a nation of only two million. Similarly, Poland can arbitrage its location between Germany and the Former USSR in a similar manner. While this factor cannot directly be influenced by a dictator or his policies, it is useful in explaining why some nations have been more successful than others in making the transition.

This is best illustrated by a quick examination of the case of Macedonia. On first examination this country bears many similarities to Slovenia. Macedonia was part of the former Yugoslavia under Tito. It was the only other country, besides Slovenia, to avoid succumbing to ethnic violence, and to secede from the communist state in a somewhat peaceful manner. The two nations are even roughly the same size, and border a long-standing member of the E.U. Yet, Macedonia has lagged far behind Slovenia, and other transition nations, in economic performance. The answer for this lies in its socio-geographic position. Instead of bolstering the Macedonian economy, the country’s position next to Greece stilted it due to cultural and territorial enmities between the two nations. While Slovenia was strengthening ties with its western neighbors, Macedonia was locked in a dispute over the country’s name and flag with Greece, which the Hellenistic republic claimed were exclusively Greek national symbols. During the 1990’s the threat of violence actually existed between the two nations, and Greece leveled a total embargo against Macedonia for over 19 months (Wren, 1995). Macedonia’s location next to what was at the time a powerful trading partner actually hindered it due to cultural conflict.

That said, simply having a good location does not make for a successful transition by itself. Macedonia’s neighbor to the west, Albania, remains less developed, due to the pre-existing conditions created by its dictator (World Bank, 2012). This is true despite Albania’s direct access to shipping and relative proximity to Italy. Albania has had no active disputes with any western economy since the fall of communist regime. Instead, a transition economy’s population demographics and location can best be thought of as a mitigating factor in attracting investment and economic growth. For example, judging from the cases of Slovenia, Macedonia, and Albania, Romania could have been relatively better off it were located next to a friendly western nation, but due to its dictator’s policies it would most likely still not have been able to be as successful as Slovenia or Poland in garnering growth through trade.

GDP Growth

In addition to showing more desirable levels of infrastructure and political stability, Nations with benign communist regimes do indeed show higher levels of per capita GDP and levels of Foreign Direct Investment. As can be seen in chart 4, the size of the gross domestic product per person is related largely the same manner, countries with the least impressive figures had the most oppressive regimes.

|

Per Capita GDP Current $U.S. |

Chart 4 |

|||

|

Slovenia |

Poland |

Romania |

Albania |

|

|

GDP per capita 1992 |

6,272 |

2,406 |

1,101 |

217 |

|

GDP Per Capita 2010 |

22,851 |

12,239 |

7,583 |

3,678 |

| Percent Change |

364.33% |

508.68% |

688.73% |

1694.93% |

Source: Word Bank

Countries with less authoritarian regimes display higher amounts of per capita GDP. This trend continued to exist in 2010. However, the percent changes reflect the inverse of the above trend, with the most oppressive regimes growing at a faster rate over 18 years. One reason for this is clear. Because the economies in countries with oppressive communist dictatorships were lower, it was easier for them to achieve more impressive growth percentages. This trend also shows that the deleterious effects of an oppressive regime are not permanent. Although Romania and Albania remain poorer than Slovenia and Poland, their smaller economies mean more prospects for growth. As they modernize, they are slowly catching up. This can be clearly seen in Romania where 646.78% of the country’s 688.73% growth took place after the beginning of real reforms in 1996. Therefore, although the more repressed Iron Curtain economies may have started the transition at a disadvantage, their long term economic prospects are far from hopeless if they continue to modernize.

Foreign Direct Investment

As privatization became necessary, investment from foreign nations became necessary in order to grow the transition economies. Once again, the relatively progressive policies of the regimes in Slovenia and Poland gave them an advantage when attempting to attract foreign monies.

|

FDI Growth |

Chart 5 |

|||

|

Slovenia |

Poland |

Romania |

Albania |

|

|

FDI (current USD) 1992 |

111,000,000 |

678,000,000 |

77,000,000 |

20,000,000 |

|

GDP (current USD) 1992 |

12,522,536,279

|

92,295,029,651

|

25,090,303,817

|

709,452,573

|

|

FDI (current USD) 1992 as % of GDP |

.89% |

.73% |

.30% |

2.82% |

|

FDI (current USD) 2010 |

366,161,963 |

9,056,000,000 |

3,453,000,000 |

1,109,558,024

|

|

GDP (current USD) 2010 |

46,908,328,072 |

469,440,132,670 |

161,623,662,681 |

11,786,099,138

|

| FDI (current USD) 2010 as% of GDP |

.78% |

1.93% |

2.13% |

9.41% |

|

Change FDI as % GDP |

-12.35% |

164.38% |

610.00% |

233.69% |

Source: World Bank

At first, the percent-based evidence in the chart may seem to support the conclusion that Poland and Romania fared the best of all (see chart 5). However, it is important to keep in mind that they are the two largest transition economies by population in the E.U. Given the size of these nations it makes sense that gross amounts of FDI inflows are more impressive than for Slovenia and Albania. When comparing nations of roughly the same size we can see that the figure is much larger for benign dictatorship countries. This is most notable when comparing Slovenia and Albania. Slovenia has roughly two thirds of the population of Albania, however the FDI figures for both 1992 and 2010 are clearly larger in Slovenia. The population differential is roughly the same between Poland and Romania, and the same trend can be seen in the FDI levels.

When viewed as percentage of the country’s GDP for that year the trends are not as clear. At first glance Romania and Albania seem to have attracted the most FDI relative to the size of their economies (see chart 5). Percent growth over the 18-year period is also the highest. Lower levels are exhibited in Poland and Slovenia. At first this pairing would seem point to a lack of direct relation between FDI and dictatorial policies. However, when one examines the forces that shape these figures, the relationship becomes apparent. Jaruzelski presided over an orderly transition from communism in Poland, which put an emphasis on privatization by western companies. Albania’s seemingly impressive percentage growth figures mask the fact that Hoxha’s isolationist policies retarded Albania’s production capacity, making its GDP much lower than other nations after the fall of communism. Even the lackluster gross FDI figures were enough to make FDI appear large as a percentage of GDP. The low FDI percentage figures in Romania reflect the Iliescu government’s effective failure to reform the country’s industrial system. Most FDI investment in the country did not occur until the early 2000’s. On the other hand, Slovenia’s small FDI inflows could possibly reflect the country’s pre-existing development. The country’s communist era ties with the west may have necessitated a less aggressive infusion of foreign monies as industrial privatization occurred. Therefore, despite the varied reactions of FDI figures to conditions in each of the nations in question after the fall of communism, the reasons for those fluctuations supports the conclusion that nations with totalitarian dictators are at an overall competitive disadvantage as they begin to make the transition.

Export Growth

After the Iron Curtain was lifted, all of the transition economies were faced with the necessity of promoting their products abroad. While some of these nations, especially Slovenia, had more experience at doing this in a sustainable manner, the countries with controlling dictators exhibited worse export performance.

|

Export Growth (%of GDP) |

Chart 6 |

|||

|

Slovenia |

Poland |

Romania |

Albania |

|

|

1992 Exports |

63% |

22% |

28% |

11% |

|

2010 Exports |

65% |

42% |

23% |

30% |

|

Percent Change |

3.17% |

90.91% |

-17.86 |

172.73% |

Source: World Bank

Under Tito’s policies, Slovenia had business ties with western nations before it seceded from Yugoslavia. It also shows the highest export figures of any of the countries in 1992, and maintained the lead in 2010 (see chart 6). While percentage growth is the lowest of any of the nations, it is important to keep in mind that because of its relatively high amounts of western trading ties it did not face as much difficulty when Soviet trading channels collapsed during the early 1990’s. During this period, Poland was well positioned to make the political transition, and this made the economic transition relatively smooth as well; the country experienced impressive export growth. The Romanian figures are perhaps the most deceptive in the above chart. By the start of the period, Romania had already been experiencing economic turmoil for roughly two years. As the Iliescu government became entrenched during 1990 the country only exported 17% of its GDP. Data from the Ceauşescu era is not available. In addition, most likely due to the weak government financial practices in the 21st century, the country was hard hit by the recession. Exports took a ten percentage point slide from 2009 to 2010 alone. For much of the interceding period exports were higher, although not approaching those levels seen in Slovenia or Poland. In accordance with Hoxha’s anti-trade policies, Albania displays the lowest level of exports as a percentage of GDP in 1992. While this allowed it to grow its export percentage quickly, it remains lower that either of the successful nations, and was lower than Romania’s for each year of the relevant period except 2010. The nations that emerged from liberal communist regimes, and developed Exim banks, exhibit more favorable data in this area as well.

Conclusion: Shadows, Economy and the Future

All together, the economic data also support that the countries with the least repressive regimes under communism fared better economically when making the transition. The common indicators of infrastructure and regulatory environment used by analysts vary inversely with the degree of totalitarian communist policy that existed in a country. While socio-geographic location is an exception to this statement, it is still useful in explaining economic differences in countries with similar dictators. Varying policies explain the degrees of economic success. In Slovenia, success was tied to the pre-existing economic and trade conditions while the country was still part of Yugoslavia, allowing it to smoothly transition while improving the quality of life. In Poland, the policy of political detente pursued by Jaruzelski throughout the late 1980’s aided in the creation of an organized democracy. The policies implemented by this government allowed Poland to take advantage of growth prospects. The lack of policy, which led to an organized transition of power to the opposition in Romania, required 7 more years of communist rule, and allowed for little positive reform. This is reflected in the country’s economic situation today; Albania continues to lag behind the other countries examined in this paper. Hoxha’s insistence on absolute control of the country extended to the total isolation of its economy, placing the country at by far the greatest disadvantage as the communist regime fell.

It remains somewhat ambiguous as to whether Poland or Slovenia has enjoyed greater economic success. Slovenia may have started out ahead, but the indicators pointed to greater growth potential in Poland. The high percentage growth of Albania and Romania also shows that despite the disadvantages inherited from their past dictatorships, it is possible for a nation to successfully make the transition in the long-run. The speed at which this modernization occurs depends on how fast a nation in the present day is overcoming the negative economic legacy of its communist regime. As all of these nations continue to modernize, there may be a need for future research on this topic.

The view of looking at historical despotic policy may also have relevance as a predictor of economic success in the present day. As many countries in the Arab world begin their transition to democracy, the degree to which the previous dictator wielded absolute control over his country’s economic and political system may impact that country’s future growth prospects, in a similar manner to what has occurred in the former Eastern Bloc. Significant differences in the religious climate, as well as technological advancement since the beginning of the central eastern European economic transition could have altered the manner in which opposition to a regime forms and remains organized. Inventions such as social media are new but powerful tools. Taking these factors into account, academics that look into the current business environment of the Arab Spring nations may benefit from this framework when making their forecasts.

Many fields of study exist in academia. These fields usually develop their own world views and thereby their own explanation of events. However, they sometimes do not bring these explanations together when researching new issues. As demonstrated in the above pages, combining a historical view of political policy in the nations of the former Iron Curtain with economic data leads to reveling results. This represents an unconventional method of explanation for many trends noticed by the business community today. This explanation has powerful implications. By looking at the degree and specific manner of absolute control which a dictator wields over a given economy, a company could predict the types and degree of difficulty that a country will face as it opens its borders for western business. This information could be useful when making long-term decisions about which new market to enter. Communism and dictatorship are not conducive to the creation of a capitalist democracy in any absolute sense. The manner in which they are implemented results in a wide degree of possible variance, in two institutions which are all too often considered monolithic. As each of these countries move forward, their stories will not simply be defined by a need to determine the best path to a prosperous future. There will also be a narrative of peacemaking with the unique shadows that exist within each country.

Works Cited

Administrative Procedures and the Supervision of Administration in Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, Estonia and Albania. OECD Publications, 1997. Sigma Papers 17.

Anzur, Terry, rept. “Poland Today: Living the Lie.” Channel 2 News Special. CBS . WBBM, Chicago, 2 Jan. 1983.

Deletant, Dennis. “Romania 1945-89: Resistance, Protest and Decent.” Revolution and Resistance in Eastern Europe: Challenges to Communist Rule. Ed. Kevin McDermot and Stibbe Matthew. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2006. 81-100.

Dempsey, Judy and Nicholas Kulish “Poland’s European Union Ties May Hinge on Elections.” The New York Times 11 Oct. 2011.

Dunn, Elizabeth C. Privatizing Poland: Baby Food, Big Business and the Remaking of Labor. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004.

De Waal, Carissa. Albania Today: A Portrait of Post-Communist Turbulence. London: I.B. Tauris, 2005.

Engelberg, Stephen. “Judging Jaruzelski; A Soviet Stooge or a Polish Patriot? The Answer May Be Long in Coming.” The New York Times 21 Sept. 1990.

“EximBank in Brief.” EximBank Romania. N.p., 2010. Web. 2 Mar. 2012. <http://www.eximbank.ro/en/eximbank-in-brief.aspx>.

“Exports of Goods and Services (% of GDP)” “Foreign Direct Investment, Net Inflows (BoP, Current US$),” “Foreign Direct Investment, Net Inflows (% of GDP),” “GDP (Current US$),” “GDP Per Capita (Current US$),” “Land Area (sq. km).” “Rail Lines (Total Route-km),” “Roads, Paved (% of total roads),” World Bank Indicators. World Bank Group, 2012. Web. 2 Mar. 2012 <http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/all>.

Financial Statements for Year 2010. SID Banka. 31 Dec. 2010. Web. 2 Mar. 2012. <http://www.sid.si/resources/files/doc/angleska_stran/SID_Bank_2010.pdf>.

Gibianskii, Leonid. “The Soviet-Yugoslav Split.” Revolution and Resistance in Eastern Europe: Challenges to Communist Rule. Ed. Kevin McDermot and Stibbe Matthew. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2006. 17-36.

Investment Reform Index 2010: Monitoring Policies and Institutions for Direct Investment in South-East Europe. OECD Publicatons, 2010.

Krikham, Kieth. Presentation on Romanian economy to visiting graduate students. U.S Commercial Service – Romania. U.S. Embassy. 28 May 2010.

Kulish, Nicholas. “Poland Leads Wave of Communist-Era Reckoning.” The New York Times 20 Feb. 2012.

McDermott, Kevin, and Matthew Stibbe. “Revolution and Resistance in Eastern Europe: An Overview .” Revolution and Resistance in Eastern Europe : Challenges to Communist Rule. Ed. Kevin McDermot and Stibbe Matthew. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2006. 1-13.

Museum of Yugoslav History, Personal visit. Belgrade. Aug. 2011. Exhibit on Tito foreign policy and propaganda image.

Palace of Parliament, Personal visit. Government of Romania. Bucharest. June 2010. Tour of chambers built for Ceauşescu.

“Prague Club Members.” Berne Union. 2012. 1 Mar. 2012. <http://www.berneunion.org.uk/pc_profiles.htm>.

Raport Roczny za Rok 2010. Kuke S.A. Web. 1 Mar. 2012. <http://www.kuke.com.pl/Raporty_roczne.php>.

Roper, Steven D. Romania: The Unfinished Revolution. Florence KY: Gordon & Breach Publishing, 2000.

Sibila, Leszek, Joanna Komperda, and Karolina Żłobecka, Project curators. Moja Nowa Huta. 2009. Muzeum Historyczne Miasta Krakowa . DVD.

Silva-Jauregui, Carlos. “Scocioeconomic Transition — The Slovenian Way.” Slovenia: From Yugoslavia to the European Union. Ed. Mojmir Mrak, Matija Rojec, and Carlos Silva-Jauregui. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications , 2004. 115-31.

Swain, Geoffrey. Tito: A Biography. London: I.B. Tauris, 2011.

Turku, Helga. Isolationist States in an Interdependent World . Farnham, Surrey, U.K.: Ashgate Publishing Group , 2009.

Unger, David C. “Editorial Notebook; General Jaruzelski Regrets.” The New York Times 5 Mar. 1993.

Wren, Cristopher S. “Greece to Lift Embargo Against Macedonia if It Scraps Its Flag.” The New York Times 14 Sept. 1995.

—

Written by: Andrew Anzur Clement

Written at: University of Southern California

Written for: Prof. Sandy Green

Date written: May 2012

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Can China Continue to Rise Peacefully?

- How to Change the Story of the Pandemic with Daoist IR

- How MONUSCO Contributed to Constructing the DRC as the ‘Dark Heart’ of Africa

- How Do Travel Vlogs Contribute to GDP’s Dominance in World Politics?

- How Did Russia Use Anti-Western Narratives To Justify Intervening In Syria?

- How Do Everyday Objects and Practices Relate to IPE?