Disciplinary Architecture[1]

The city has always been and continues to be a resource for power (Hirst, 2005). Predominately, this power has been exercised on populations through the use of extensive surveillance by elites in government, the armed forces and law enforcement agencies (see Foucault 1975). Surveillance and the architecture of the city share an intimate relationship, with surveillance being used as a method of control and a symbol of power (Goss, 2010). Surveillance of the city has produced ‘architecture of spies’ which become a spatial apparatus harnessing disciplinary processes within our cities. The cities in conflict from ancient Greece and Rome through to humanitarian tragedies in Sarajevo and Kigali to asymmetric warfare in Baghdad and Kabul have heavily relied on intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) for their survival.

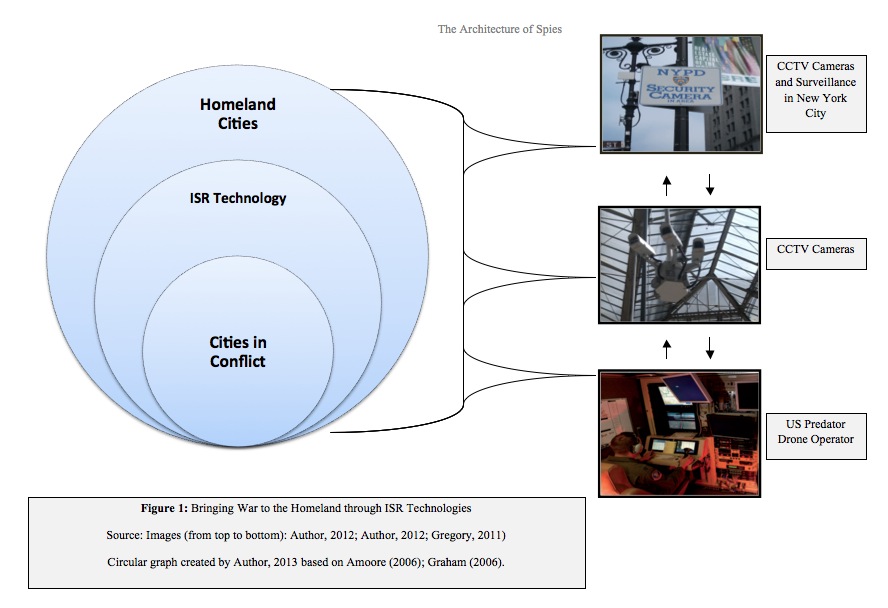

In an age of technological development the boundaries to surveillance are unclear, warping around cities through the convergence of databases and cameras to encompass and dominate every aspect of space possible. As Lyon (2007) has argued the revolution in military affairs (RMA), and the rise of a networked way of thinking in military strategy to combat the asymmetric terrorist threat has made surveillance ubiquitous. Communication between architecture and surveillance is rapidly transforming from Benthem’s Panopticon and Haussmann’s beloved boulevards to enforce discipline on space for military and security purposes. Amoore (2006) and Graham (2004) argue war, with reference to the War on Terror (WoT), is being brought closer to home and into our cities by securitising technologies (Figure 1).

In this essay the main objective is to understand how surveillance and the city work together to contribute towards a blurring between military and/or law enforcement agency practices with the work of architects and planners. Therefore, I will discuss the contention that the distinction between the working practices of military/police commanders and urban planners are increasingly blurred in the context of conflicted cities.

This essay far exceeds traditional conceptions of the spatiality of war including the fortification of walls, fences and castles. My concentration throughout is not merely on specific forms of the built environment, but their wider spatial patterns (Hirst, 2005). The discussion of the blurring of working practices will reveal how surveillance is being mobilised as a weapon for war in Baghdad through US unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and ISR technologies. However, the critical turn within this paper argues such surveillance technologies are being installed within the infrastructure of the ‘home’ city as the WoT comes back to haunt the homeland. It is not only the city of war or the conflicted city that is experiencing a blur within working practices but also the cities symbolic of democratic peace. Finally, I will argue that Foucault’s (in Dandeker, 1975) envisagement of the decentralisation of surveillance is becoming part of everyday practice which combined with technology has perpetuated blurring between urban planning/design and military/security practices.

Surveillance & Verticality

Surveillance

Space, power and surveillance were first linked by Benthem’s (1791) account of the ‘Panopticon’. The panopticon had the intention of securing prisoners through omnipresent and omniscient surveillance architecture. Foucault (1975) argued there was a great importance to the continuous use of surveillance through a decentralised network because it offered a subtle method of control over human interactions. One of the most literal interpretations of the surveillance discourse can be seen in the City of Paris where in the 1860s the architect Baron Haussmann refined and rationalised the ‘art of war’. Like philosophers and military commanders at the time, Haussmann believed if people were visible they could be controlled through a self-imposed discipline from the constant fear of being discovered to have wronged, a kind of public vigilance (Elden, 2001). The surveillance logic of militarised discipline replaces the religious belief of exclusion to generate a feeling of being ‘secure’ and becoming rooted within the architectural epistemology and practice.

Haussmann’s redesign of Paris with Le Grands Boulevards and other architectural sensations revolutionised the relationships between cities, architects and military commanders. However, in the contemporary city architecture and securitisation are imagined through the networking of surveillance entities and produce a digital geography (Murakami-Wood, 2007). Delueze and Guatarri (1980) have advanced this kind of critical thought within urban geography by emphasising the importance of interactions between objects, their performances coming together through flows and connections. Thinking of surveillance through both prisms produces architectures of power and spying over given territory in order to dominance certain kinds of spaces.

Verticality

In the 21st Century city of conflict, surveillance is being used in powerful ways by harnessing military technologies including General Atomics’ MQ-1 Predator drone to see from above the city (General Atomics, 2013). Architectural writers including Graham and Hewitt (2012) have noted the power of skyscrapers and how verticality is increasingly being mobilised to sustain social hierarchies within modern cities. The $1 billion Antilia apartments in Mumbai is allegorical to the logic that verticality equates to power over territory through the ability to watch, whilst those uneducated and poor remain down below in the slums. In both military and planning cases the vertical perspective eases classification of identities, in the case of war it is the enemy and ally, and in planning the divides of power are based on wealth, rich and poor (Weizman, 2002). Of course these classifications are dangerous as cultures, traditions, religions, family traits and norms are simply reduced to ‘them’ and ‘us’ (Gregory, 2004). Both the vertical surveillance reinstalls geopolitical imaginaries of the city that produce an affective logic to architecture and war. Therefore, as will be explored in this paper it is not only the physical practices of military/police commanders and architects/planners which are being blurred but fundamentally the urban epistemologies locked in the mindset (see Dittmer, 2010; Pile, 2010).

Nonetheless, this paper avoids focussing too much on the verticality and attempts to map the power relations between vertical and horizontal surveillance to avoid pre-determining military urban power relations. As Williams’ (2013:225-226) critically argues the practice of looking down on the battlefield “is imbued with an imperialistic ‘god’s eye’ perspective” producing a ‘mono-perspectivism’ which has “precluded other directions of gaze from being acknowledged or critiqued”. It is more enriching to the analysis of this paper in understanding the blurring of military and planning practices to explore the relationship between the vertical and horizontal perspectives within cities of conflict.

War on Terror: Paris and Baghdad

Bush’s ‘shock and awe’ doctrine in the Iraq War, 2003 was part of the broader WoT campaign that radically transformed the cityscape including Baghdad through the use of overwhelming military power (Anderson, 2004). The purpose of this rapid dominance strategy was to enhance battlespace awareness for US and coalition forces to enable the gain and security of territory. Throughout the WoT indoctrination, Bagdad has been subject to ubiquitous surveillance through forms of sophisticated military technologies including drones and networked ‘spy’ cameras. Baghdad has gone through similar urban practices undertaken by the architect Haussmann in Paris 140 years previous. The Haussmannisation of Paris can be translated onto the military tactics being deployed in Baghdad. The following account revives a historical geographical of surveillance that blurs the working practices of the military and urban planners.

From Paris…

Foucault (1975) notes real political power is delineated by a silent war that re-inscribes banal social organisation and structure including economic and political power relations, and cultures. Surveillance has become critical in this respect to creating ‘architectures of fear’ that prevail over the cityscape on a rationale of being seen (Pain and Smith, 2008). The art of governmentality stitches together military and architectural epistemologies to design urban spaces that are omniscient and omnipresent to produce fear.

Haussmann’s vistas created a surveillance that cuts-across the city, empowering statesman and law enforcement bodies with a panoptical watch. Fear as a result of a sense of being watched became normalised in the material fabrics of the urban environment allowing fear to creep into the subconscious and routinise actions (Katz, 2007). Therefore, surveillance generates what Flusty (1994; 2001:01) coins ‘building paranoia’ in where citizens are fearful of the urban fortress that is designed “to command, protect, socialize and dominate the surrounding urban population”. The drone commands and controls particular geographical futures through the use pre-emptive surveillance using a God-like power to determine the future of identities within cities including the categorisation of enemy, ally or civilian (Gregory, 2011). Architectural practices of Haussmann predetermined economic status through dividing the city into arrondissements based on people’s economic status privileging the aristocrats in the centre with a panoptical view of the poor areas or banlieues (Schnieder, 2008). Haussmann’s reinvention of Paris like the American invasion of Baghdad is reflective of the capitalist ideology to control and oppress territory (Harvey, 2011). Architectural practices of Haussmann’s surveillance enabled privileged views to those wealthy enough to reside in the centre in the large squares and quarters around the Opera, restaurants and cafes (Carmona, 2002). Haussmann strategically moulded Paris into a geometric grid that could easily be navigated and watched to maintain elite territorial control of the city.

…To Baghdad

Similar to Haussmann, the Coalition invasion into Baghdad led by the US attempted to mould the city into a geometric grid through creating an urban panopticon and sense of building paranoia (Flusty, 1994; 2001). Spaces were colonised, subject to governmentality to be become an extension of dominant power in the WoT (see Lefebvre, 1991[1905]). However, in simplifying this urban labyrinth to enable ubiquitous observation, vertical surveillance has become crucial in projecting power over territory.

The MQ-1 Predator UAV is part of a pervasive military matrix re-carving the geopolitical landscape using state-of-the-art surveillance monitoring equipment enabling the combat zone to see (Graham in McDonald et al, 2010). ISR technologies have become sophisticated through the evolution of the WoT with the ability to identify distinctions between the civilian and target to reveal the most intricate details. Aerial surveillance technologies are knowledge-producing and move beyond geography as a flat ontology. Vertical surveillance produces a politics that translates onto the landscape below in which the city becomes re-constructed (Gregory, 2011). Unlike Haussmann’s surveillance of Paris, the verticality of surveillance in Baghdad is not bound by physical spatialities as surveillance is networked across the cityscape and part of a globalised battlespace. UAVs rely upon a series of interlinking networks to ensure the person observing the city is located hundreds of miles from the battlefield without compromising accuracy and time (Bookstaber, 2000). Real-time footage is uploaded onto screens of the observer and also enables other observers to communicate with each other and surveillance technologies on the ground through a Facebook style chat (Kaplan, 2006). Therefore, the political doctrine of the US and coalition forces to end insurgency in the area is communicated through these networks and transposed onto urban spaces despite the observer being located thousands of miles ways. Surveillance becomes globalised but also distant as well as borderless and no longer confined to the boulevards and streets of the city. The Predator regularly surveils to project American sovereignty and authority onto the Iraqi landscape making sovereignty borderless and a de jure right (Williams, 2009). The use of drones dismantles the demarcations of frontline warfare and extends the American frontier to colonise Baghdad’s city space by using architectural tools of surveillance.

Horizontal surveillance is also important within the contemporary military architecture of our cities with ISR technologies including the Xaver 400 countering the physical geographical spatiality of the city. The Camero Xaver 400 has the ability to ‘see through walls’ by using ultra-wideband technology producing an inverse geometry where the inside space becomes visible to the outside, and smooth space is dominated into striated (Weizman, 2006; Delueze and Guatarri, 1980). In Paris surveillance was limited to only the architectural vistas created by Haussmann, but the Xaver 400 transports these vistas to anywhere within the urban milieu to allow combat teams to ‘step into the unknown’ (Camero, 2013). The technology creates a digitised geography connected through complex networks to the Predator to enhance situational awareness as part of the network-centric way of thinking war (Alberts et al, 1999; Cebrowski, 2000). The information-age unlike 1860s Paris de-spatialises and fragments surveillance within and between actors operating in the network. Nonetheless, Harvey’s (2011) interpretation of the Haussmannisation of Paris argues against this claim to suggest the creation of squares and quarters was a way of decentralising surveillance into the everydayness of the city. Building squares around cafes and restaurants empowered the average person with a panoptical vision triggering people to keep watch over each other similar to the public vigilance campaigns seen within homeland cities.

Lefebvre’s claim that space is inherently political chimes with the above analysis, but also city-space can be an extension of the political (Lefebvre, 1991[1905]). These two very different cities are combined through the surveillance logic, bound by the vertical and horizontal perspectives to the geographical ontology. Communication between vertical and horizontal perspectives builds a three-dimensional and volumetric geopolitical landscape that is not just concerned with war but also the power-relations between urbanism and surveillance (Forsyth, 2010; Sassen, 2010). Architectural and military practices are blurred through dominating but also decentralised networks of surveillance which is echoed by this historical-geographical prism.

Compassionate Planning or Spying?

Britain had the second largest number of troops deployed in Baghdad after the US and therefore, as a result still faces a prominent threat from terrorism. Similar to other homeland cities, London networked its cityscape with the most sophisticated surveillance technologies from facial recognition to automatic patrolling cameras to monitor suspicious activity. Amoore (2006) and Graham (2004) argue the adoption of surveillance technologies within the city bring the WoT closer to the homeland. Both scholars suggest technologies make the city an extension of the political battlefield like the Haussmannisation of Paris that projected a politics of wealth and elitism on the city. Architecture and war organise spaces in subtle ways, evident from the cases of Paris and Baghdad (Hirst, 2005).

Compassionate Planners

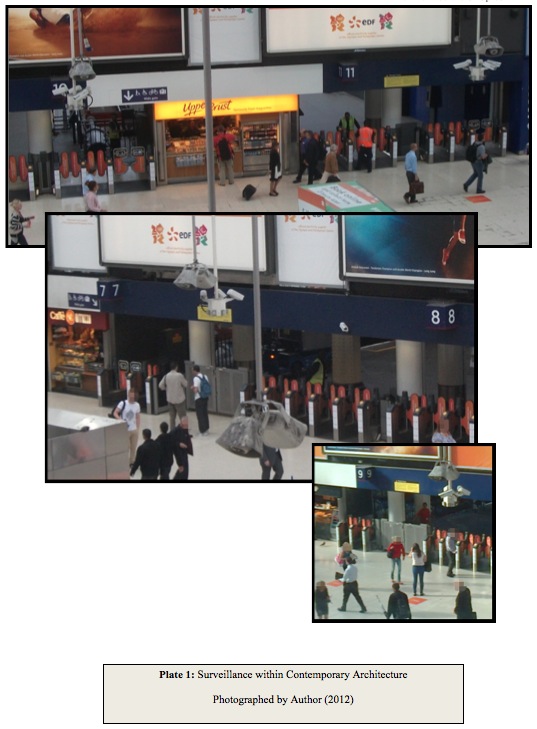

In the post-9/11 environment an “anxious urbanism” has been produced, especially around sites of critical national infrastructure including transport hubs and financial spaces which are recognised by terrorists to cause the most damage to the city (Coaffee in Graham, 2004). Lord West’s Review of the UK’s counter-terrorism strategy, CONTEST articulated protective security needed to be embodied “into the built fabric of cities.” (Coaffee, 2010). Adair (2009) refers to this as the ‘quotidian invisibility’ of the infra-ordinary in how surveillance becomes part of the background of urbanism or as Murphy (2012:174) calls an “absent presence”. CCTV has become a popular policing measure to respond to crime and terrorism in Britain, but the panoptical shift of the 21st Century seeks to embed itself within the everydayness of the city to keep people safe. In the UK’s busiest railway station London Waterloo, the main concourse in 2012 was recently ‘opened up’ to enhance the visibility of crowds moving through the stations during the Olympics to uphold its commitment to protect commuters against crime and acts of terrorism (SSM, 2012). Static Phillips cameras were located high above the ground within the towering vertical architectures of the station to perform a panoptical logic of security (SSM, 2012; BTP, 2012). Multifunctional dome CCTV were lofted into ceilings in order to perform similar tasks and look down the urban spaces below (Observant Participation, 02/08/2012) (Plate 1). Therefore, surveillance within London aims to secure and protect members of the public as part of the national security by becoming intertwined within the socio-political fabrics of the banal environment.

Spies

Similar to Haussmann’s surveillance of Paris, space becomes a container for the eye of the observer in which power-relations are drawn as the observed is powerless over the person undertaking surveillance (Kosekla, 2000). In all three sites of London, Baghdad and Paris surveillance dominates space by colonising territory through the projection of political power. In London the anti-surveillance activist group Big Brother Watch (2012) argues CCTV in London is an extension of spying by intelligence and law enforcement agencies seeking to control the public. Lyon (2007) along with Amoore and Hall (2008) argue the practice of profiling, the extrapolation of information from people based on personal characteristics such as ethnicity and sex, relies on political (constructed) strengthens such claims as war is fought within the homeland.

The Bush ‘effect’ through the WoT indoctrinates architecture of security thinking through pre-emptive surveillance within home cities. The role of CCTV and surveillance technologies project this politics onto particular places and spaces making homeland cities part of the political battlefield and wrapped up into historical geographies of the Haussmannisation of Paris. Homeland cities are no longer exempt from the blurring between military and an architectural practice as surveillance is not only subject to the city in conflict but increasingly part spaces of flows that infiltrate the global sphere (Castells, 1996).

The Architecture of Surveillance

The concept of surveillance has been central in theorising the relationship between war, power and architecture. Various technologies and methods of surveillance are common features of urban design and architecture in almost any context. From observation towers in medieval citadels to espionage in the Cold War from the biometric checkpoints at Israel/Palestine border to drone technologies in Baghdad, Islamabad and Kabul, which now haunt the homeland cities through CCTV, checkpoints and identification cards. In the verticality of surveillance in drone warfare there is an immediate technological transfer between war zones and civil urban life as well as powerful connections to the historical surveillance methods in Paris. War and surveillance also come back to haunt the homeland through the instalment of CCTV into everyday architectures, decentralising the gaze in order to become ubiquitous above and across the cityscape (Foucault, 1975).

Surveillance practices have always dismantled demarcations between military urbanism and civil life, thus this has intertwined the professions of the military and police together with urban planners. It is not only a lack of demarcation between military / police commanders and urban planners but an integration of war-like technologies including scanners, drones, micro-cameras to name but a few into homeland cities. Urban spaces are undergoing radical change by introducing surveillance technologies which exert political power on the spaces located within the gaze. The continuation of blurring between surveillance practices but also the Orient and homeland cities is inevitably producing a global ‘architecture of surveillance’ (Said, 2003[1973]).

Bibliography

Adair, G. (2009) The Eleventh Day: Perec and the Infra-Ordinary, The Review of Contemporary Fiction, 29(1), 177-188.

Alberts, D. Garstka, J. Stein, F. (1999) Network Centric Warfare: Developing and Leveraging Information Superiority, 2nd Edition, Washington, CCRP.

Amoore, L. (2006) Biometric Borders: Governing Mobilities in the War on Terror, Political Geography, 25(3), 336-351.

Amoore, L. (2009) Algorithmic War: Everyday Geographies of the War on Terror, Antipode, 41(1), 49-69.

Amoore, L. And Hall, A. Taking People Apart: Digitised Dissection and the Body at the Border, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 27(3), 444-464.

Anderson, L. (2004) Shock and Awe: Interpretations of the Events of September 11, World Politics, 56(2), 303-325.

Benthem, J. (1791) Panopticon or the Inspection-House Vol. 2, Lincolns Inn, London, Digitised by Google Books.

Bookstaber, D. (2000) Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles: What Men Do In Aircraft and Why Machines Can Do It Better, Defense Technical Information Center (DTIC), Virginia.

BTP, British Transport Police Officer. (2012) Interview held 29th August, 2012 at London Waterloo Railway Station.

Camero. (2013) Xaver 400, http://www.camero-tech.com/product.php?ID=39 [Accessed 26/02/2013].

Carmona, M. (2002) Haussmann: His Life and Times, and the Making of Modern Paris, Ivan R Dee Inc, London.

Castells, M. The Rise of the Network Society, Blackwell Publishers, Massachusetts.

Cebrowski, A. (2000) The Implementation of Network-Centric Warfare, Office of Force Transformation, Pentagon, US.

Coaffe, J. (2004) Recasting the “Ring of Steel”: Designing Out Terrorism in the City of London? in Graham, S. Cities, War and Terrorism, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford.

Coaffe, J. (2010) Protecting Vulnerable Cities: The UK’s Resilience Response to Defending Everyday Urban Infrastructure, Chatham House, London.

Deleuze, G. And Guattari, F. (1980) A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, University of Minnesota, Minnesota.

Dittmer, J. (2010) Popular Culture, Geopolitics and Identity. Rowman and Littlefield, Maryland.

Driver, F. (1985) Power, Space and the Body: A Critical Assessment of Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 3(1), 425-46.

Elden, S. (2002) Mapping the Present: Heidegger, Foucault and the Project of Spatial History, Continuum, London and New York.

Forsyth, I. (2010) Shadow Chasers: Exploring the Vertical and Angular Geographies of Camouflage, Backdoor Broadcasting, http://backdoorbroadcasting.net/2010/12/ilsa-forsyth-shadowlands-exploring-the-vertical-and-angular-geographies-of-camouflage/ [Accessed 01/03/2013].

Foucault, M. (1975) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Penguin Publications, London.

Flusty, S. (1994) Building Paranoia: The Proliferation of Interdictory Space and the Erosion of Spatial Justice, Los Angeles Forum for Architecture and Urban Design, West Hollywood, California.

Flusty, S. (2001) The Banality of Interdiction: Surveillance, Control and the Displacement of Diversity, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 25(3), 658-664.

General Atomics. (2013) Predator UAS, http://www.ga-asi.com/products/aircraft/predator.php [Accessed 26/02/2013].

Gibbons, H. (2012[1919]) Paris Vistas, Digitised by Project Gutenberg, The Century Company, New York.

Graham, S. (2004) Cities, War and Terrorism, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford.

Graham, S. (2010) Cities under Siege: The New Urban Militarism, Verso, London.

Graham, S. (2010) Combat Zones that See, in Macdonald, F. Hughes, R. And Dodds, K. Observant State: Geopolitics and Visual Culture, I.B. Tauris, London.

Graham, S. And Hewitt, L. (2012) Getting off the Ground: On the Politics of Urban Verticality, Progress in Human Geography, 37(1), 72-92.

Gregory, D. (2004) The Colonial Present: Afghanistan, Palestine and Iraq, Wiley-Blackwell, London.

Gregory, D. (2011) From A View To A Kill, Theory, Culture and Society, 28(7-8), 188-215.

Goss, P. (2010) Surveillance, Architecture and Society, http://ezinearticles.com/?Surveillance,-Architecture-and-Society&id=3557213 [Accessed, 26/02/2013].

Harvey, D. (2011) The Enigma of Capital and the Crises of Capitalism, Profile Books Ltd, London.

Hirst, P. (2005) Space and Power: Politics, War and Architecture, Polity Press, Cambridge

Human Rights Watch, (2009) Precisely Wrong: Baghdad Civilians Killed By US Drone-Launched Missiles, Human Rights Watch, New York.

Kaplan, R. (2006) Hunting the Taliban in Las Vegas, The Atlantic Monthly, September, http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2006/09/hunting-the-taliban-in-las-vegas/5116/ [Accessed, 20/01/2012].

Katz, C. (2007) Banal Terrorism, in Gregory, D. And Pred, A. (eds.), Violent Geographies: Fear, Terror and Political Violence, Routledge, New York.

Koskela, H. (2000) ‘The Gaze without Eyes’: Video-Surveillance and the Changing Nature of Urban Space, Progress in Human Geography 24(2), 243-265.

Landau, S. (2010) Surveillance or Security? The Risk Posed by New Wiretapping Technologies, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Massachusetts.

Lefebvre, H. (1991[1905]) The Production of Space, Translated by Nicholson-Smith, D. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford.

Lico, G. (2001) Architecture and Sexuality: The Politics of Gendered Space, Humanities Diliman, 2(1), 30-44.

Longbottom, W. (2011) World’s Most Expensive House Lies Abandoned…Because Billionaire Owners Believe it would be Bad Luck to Move in, Daily Mail Online, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2053231/Worlds-expensive-house-Antilia-Mumbai-lies-abandoned.html [Accessed 26/02/2013].

Lyon, D. (2007) Surveillance Studies: An Overview, Polity Press, Cambridge.

Murakami Wood, D. (2007) Beyond Panopticon? Foucault and Surveillance Studies, in Crampton, J. And Elden, S (ed). Space, Knowledge and Power, Ashgate Publishing Ltd, Hampshire, 245-263.

Murphy, P. (2012) Securing the Everyday City: The Emerging Geographies of Counter-Terrorism, Doctoral Thesis, Durham University.

Neela, Sky is. (2012) Let’s Drone Karachi, http://skyisneela.blogspot.co.uk/2012/02/lets-drone-karachi.html [Accessed, 26/02/2013].

Pain, R. And Smith, S. (2008) Fear: Critical Geopolitics and Everyday Life, Ashgate, London.

Pile, S. (2010) Emotions and Affect in Recent Human Geography, Institute of British Geographers 35(1). 05-20.

Sassen, S. (2010) When the City Itself Becomes a Technology of War, Theory, Culture and Society, 27(6), 33-50.

Said, E. (2003 [1978]) Orientalism, Penguin Books, London

Schneider, C. (2008) Police Power and Race Riots in Paris, Politics Society, 36(1), 133-159.

SSM, Shift Station Manager. (2012) Interview held 23rd June 2012 at London Waterloo Railway Station.

Weizman, E. (2002) Introduction to the Politics of Verticality, Open Democracy, http://www.opendemocracy.net/conflict-politicsverticality/article_801.jsp [Accessed 26/02/2013].

Weizman, E. (2006) Walking Through Walls: Soldiers as Architects in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, Radical Philosophy, 36(1), 8-22.

Williams, A. (2009) A Crisis in Aerial Sovereignty? Considering the Implications of Recent Military Violations of National Airspace, Area, 42(1), 51-59.

Williams, A. (2013) Re-Orientating Vertical Geopolitics, Geopolitics, 18(1), 225-246.

[1] The essay is dedicated to all those who supported my undergraduate thesis, in particular to the staff at London Waterloo Railway Station who provided a critical empirical insight into everyday urban practices of surveillance and security.

—

Written by: Connor Lattimer

Written at: Royal Holloway, University of London

Written for: Dr. Noam Leshem

Date written: March 2013

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Is the European Union’s Institutional Architecture in Multiple Crisis?

- Reform of the Global Financial Architecture: The Role of BRICS and the G20

- Everyday Insecurity in Gaza: Experiencing Blockade, Displacement and Panopticism

- Are We Living in a Post-Panoptic Society?

- The Emergent Role of Cities as Actors in International Relations

- Beyond Agent vs. Instrument: The Neo-Coloniality of Drones in Contemporary Warfare