The Syria Dilemma

By: Nader Hashemi and Danny Postel (eds)

Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2013

In one of the more amusing episodes of the successful satirical British sitcom Yes, Prime Minister, titled, “A Victory for Democracy,” the eternal bureaucrat Sir Humphrey Appleby explains in brief to his political master, Prime Minister Jim Hacker, the secrets of British foreign policy. More precisely, Sir Humphrey explains the manner in which the bureaucracy deals with the hyperactivity of the politicians during crises in the international arena. In the first stage, says Sir Humphrey, we advise the prime minister not to do anything, because there is no need to act since matters will straighten themselves out. In the second stage, when the affair blows up in our face, we explain to the politicians that perhaps there was a need to act at the beginning, but now it is already too late to do anything.

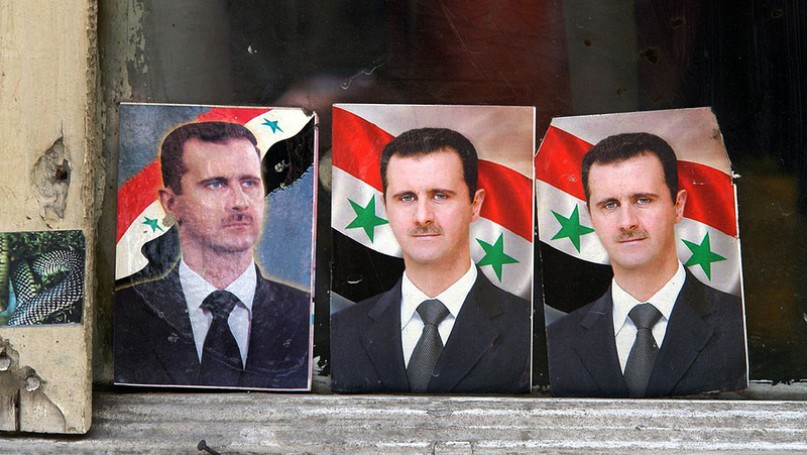

Recalling this episode, it is almost impossible not to think of the Syrian Revolution. When it began in the spring of 2011, it was looked upon as a continuation of the “Arab Spring” that had burst forth in other Arab states of the Middle East. The events in Syria started out as a widespread yet peaceful and non-violent protest against the regime of Bashar al-Assad. There is little doubt that initially the protest enjoyed broad popular support. If the numbers of people who participated in the demonstrations all over the country did not reach the millions seen in Tahrir Square in Cairo, they did reach the hundreds of thousands. In addition, the demonstrations lacked any signs of extremism based on ethnic or religious grounds. No jihadists were visible among the masses of people who came to the village and town squares to demonstrate. The extremists and jihadists began to appear only in the following years. They streamed into Syria in large numbers from all over the Arab and Muslim world with the aim of participating in a holy war, jihad, against the “heretical” Alawite regime ruling the country.

The Syria Dilemma, edited by Nader Hashemi and Danny Postel, does well in dealing with the dilemmas currently facing Syria, and others like them. The book is a collection of articles and opinion pieces on what is happening in Syria today and how to deal with the question of what the international community should do in face of the enormous human tragedy occurring there. This is not a book about the revolution itself or its political and social roots or the course of the subsequent hostilities. Rather, the book focuses on the mainly moral and ethical, but also practical, questions confronting Western public opinion, and the decision makers in the West in particular, in face of the Syrian tragedy.

During the initial period of the revolution all that the then-US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton could say was that American senators returning from Syria had told her that Bashar al-Assad was a reformer and his efforts at reform should be supported. Moreover, she declared that Syria was not Egypt or Tunisia (Interview with Bob Schieffer of CBS’s Face the Nation http://www.state.gov/secretary/rm/2011/03/159210.htm, 27 March 2013). These were precisely the claims made by al-Assad himself in an interview he granted to the Wall Street Journal in January 2011, not long before the outbreak of the protest demonstrations in his country. In this interview the Syrian president prophesized that the “Arab Spring” would by-pass Syria (Wall Street Journal, 30 January 2011).

The way the international community, and especially the Americans, reacted to the events in Syria stood in sharp contrast to the manner in which they had met the Egyptian revolution of 25 January 2011. There, just one day after the outbreak of massive anti-regime demonstrations, President Barak Obama himself called upon Egyptian President Husni Mubarak to step down.

Despite the dearth of international support and encouragement, the protests in Syria did not subside, and President Assad decided to use armed force against them. The activation of the army and the resort to unrestrained violence simply poured oil on the fire, and while it may very well have made it possible for Bashar al-Assad to remain in power, it led to disaster; what had begun as a relatively peaceful revolution turned into a bloody and protracted civil war that shattered the fabric of the Syrian state. Many Syrians soon became refugees in their own land or abroad, fighting to survive. The place of the peaceful protesters was taken up by armed groups, most of whom champion extremist ideologies. Up to the present time, the regime has managed to hold its ground against these forces.

Any situation can be simplified or made complex, including the current situation in Syria. According to the simplified portrayal, a whole nation is seeking its freedom against a dictatorial ruler who wants to keep the power bequeathed to him by his father. According to the more complex picture, the struggle for freedom led to a terrible upsurge in bloodletting because of the failures of the revolution’s perpetrators and their inability to unite their ranks and develop a competent military and political leadership. Bishara Boutros al-Ra`i, Patriarch of the Maronite Church in neighboring Lebanon, who, like many other members of the Christian minority in the Levant, felt compelled to become an adherent of Bashar al-Assad, has stated in this connection that the desire for democracy does not justify and is not worth one drop of blood.

On the one hand, the Syrian regime is secular in character, and as such it needs all the support it can get against religious extremism. This is the way Russian President Vladimir Putin views the situation, as do many others in Syria, the West, and the U.S. On the other hand, Bashar’s dictatorial regime has no qualms about employing violence and murderous brutality, including advanced missiles and chemical weapons, in order to suppress the aspirations for freedom of the Syrian people. From another angle, the international community seeks to maintain international law and the basic rules of international relations, that is, action by consensus and with international legitimization. In practice, however, this means inaction, because the Security Council is plagued with a paralysis that prevents it from adopting any resolution providing for action in regard to Syria.

In some ways the civil war in Syria is reminiscent of others, for example, the civil war in Spain prior to World War II. There too the republican side enjoyed the support and sympathy of the world, but at the same time the side of the rebels led by General Francisco Franco received aid in arms and fighters from the fascist regimes. These enabled Franco to come out victorious, although at the price of a million persons killed. Anyone who wants to find consolation in this gloomy comparison with Spain can perhaps take comfort in the fact that in Spain some glowing coals remained, and following Franco’s death some 36 years later they managed to return democracy to the country.

There is no question that a terrible tragedy is taking place in Syria, and it is clear that the person who stands at the head of the Syrian regime, Bashar al-Assad, and even more, the dynastic and dictatorial structure and character of the regime he commands, stand at the root of the crisis. Also conspicuous is the international community’s failure to act in the face of the unfolding tragedy. The book under review is a fitting monument to this failure to act, or even as contributing author Afra Jalabi puts it in her excellent article “Anxiously anticipating a new awn voices of Syrian activism”: the cover of the February 23, 2013 edition of the Economist bore the headline” Syria; the death of a country,” a more apt headline would have been the betrayal of a country. (p. 91)

After reading this book, which clarifies and succinctly sums up the essence of the Syrian crisis and the dilemmas it raises, it is clear that there is no analysis of the Syrian regime within the book’s essays. This is arguably required to present the position of the regime and its supporters. However, the reader hardly feels this absence because the various articles that are included–being the most outstanding and representative items published in the Western press during the last three years–are solid and comprehensive enough to reflect every aspect of the Syrian tragedy.

It is almost impossible not to sympathize with the Syrians rebelling against their regime, at least those who raised the banner of revolt three years ago. However, their weaknesses became all too evident and so they found it difficult to gain the support of the world, which usually comes down on the side of the winner. At the same time, the weakness of the West has also become conspicuous. This is especially so of Washington, which finds it difficult to commit itself to fighting for a purely humanitarian cause that holds out almost no promise of material gain – oil, for example, as explained by contributing author Michael Ignatieff in his article “Bosnia and Syria: Intervention Then and now, when he writes: “interventions will not occur until interveners can identify with cause that democratic electorates in western states can make their own…”(p.49), and therefore warns rightly that “if they (the Syrian rebels) win their freedom, they will have no reason to thank us and they will have no inclination, as they settle their scores. To listen to anything from the West, or anyone else, but due to our inability to act consequently in their defense, we have no reason to wonder whether Syria will survive once they win.”(p.58)

A different view is presented by Richard Falk in his article “What should be done about the Syrian Tragedy”. Falk calls for a solution to the crisis and emphasis rightly that: “To stand by is unacceptable, but to act without some realistic prospects of improving the situation is equally unacceptable.” (p. 62). But then he goes on to explain why actually there is nothing to do about this tragedy but to pray in a hope that things will somehow straighten themselves out. Falk explains that: “Without greater diplomatic pressure from both geopolitical proxies, the war in Syria is likely to go on and on with increasingly disastrous results…”.(P 67), and “For one thing, an effective intervention and occupation in a country the size of Syria, especially if both sides have significant levels of support as they continue to have, would be costly in lives and resources, uncertain in its overall effects on the internal balance of forces, and involve an international commitment that might last more than a decade.” (P 68.) So what is left according to Falk is to hope and pray: “If the imagination of the political is limited to the “art of possible” then constructive responses to the Syrian tragedy see, all but foreclosed. Only what appears to be currently implausible has any prospect of providing the Syrian people and their nation a hopeful future, and we need the moral fortitude to engage with what we believe is right even if we cannot demonstrate in advance that it will prevail in the end”.” (p.75)

Indeed, also deterring Washington is the consideration that involvement in that cause could prove to be very costly, both in terms of human life and economic resources, and it could even turn into a treacherous quagmire like Afghanistan or Iraq. Indeed, Nader Hashemi and Danny Postel make this argument when they write in the introduction to the book, entitled: Why Syria Matters ?: But the shadow of Iraq very much looms over the Syrian debate. Both the Iraq and Afghanistan wars have created deep and wide skepticism about military intervention, particularly led by the US Iraq is a reference point for many opponents of intervention in Syria.” They quoted a senior Israeli diplomat as having noted that: “in my meetings with American policy makers I often detected a conversation between ghosts, the ghosts of Afghanistan and Iraq are vying with the ghosts Rwanda and Kosovo”(pp 10-11).

Thus, one can understand Shadi Hamid’s cry in his article “Syria is not Iraq: Why the Legacy of the Iraq War keeps us from doing the Right thing in Syria”: “In due time, the Obama administration inability or unwillingness to act may be remembered as one of the great strategic and moral blunders of recent decades. Hoping to atone for our sins in Iraq, we have overlearned the lessons of the last war. I only wish it wasn’t too late.” (Pp.26-27)

The various essays in this book reflect the myriad of contrasting positions on the issue of Syria held by informed people in the West, for and against intervention, for and against the rebels. It is interesting to find out that at the end the reader is being left with no answer, this is to say a realistic plan or solution to the Syrian Crisis. It seems that for such an answer a statesman (not a politician) is in a need, and not necessarily intellectuals and researches who can analyses reality and usually also criticizes policies of the government on a moral basis, but hardly dare to suggest how to change such policies or such reality. Anyone reading this book will come to understand the factors inducing the world to continue standing aside. Some readers will undoubtedly conclude that the reluctance of the international community to intervene is justified, while others will surely view this restraint, this failure to act, as blameworthy. However, as usual, history’s final judgment must be left to the future.