This week sees the students at CEFAM absent and enjoying their mid-semester vacation. This means things quiet down a little on campus, though the work for professors and administrators continues apace with mid-term exams to be graded, mid-semester grades to be determined, and a lot of preparation for the final six weeks of classes being undertaken, too.

For me, it has been a chance to plan ahead a little bit and think about the summer semester courses I will teach this year. I will teach two courses this summer – ‘Issues in International Politics’ being the first and ‘Dimensions of Diversity’ being the second. Designing these courses, or renewing them really, is an annual event and what makes the summer particularly challenging to plan for is the limited time with the students (20 sessions instead of 26 sessions) and the truncated length of the semester (5 weeks instead of 13 weeks).

Things that work wonderfully well in a fall or spring semester don’t always work as well in the summer. For example, in a regular semester I can ask students to submit a short research paper after about six weeks, give them feedback on that paper, and then request a longer, more difficult and more involved research paper due at the end of the semester. This doesn’t work in the summer where a ‘midterm paper’ would be due about 8 days into the course, and I would struggle to provide feedback quickly enough to the students to be of any use for a research paper due only a couple of weeks later.

Yet summer also sees me enjoy, from time to time, very small classes and this opens up possibilities for changing the way a course is delivered entirely. For example, a couple of years ago I taught a summer class of only 6 students. Any notions I had of pushing them into group presentations immediately vanished as did the idea of lecturing to such a small group for an hour a day. Even with my interactive lecture style there would be only six other voices in the room which doesn’t make for the best classroom experience.

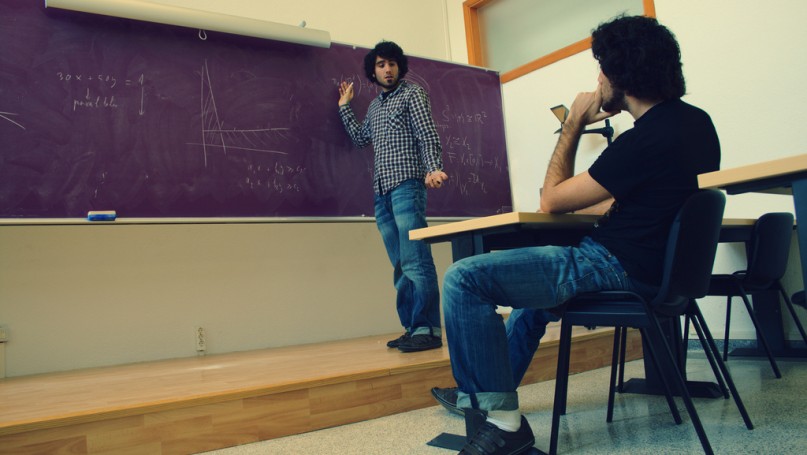

Instead, what I did then, was to take a little inspiration from a former professor of mine back in Australia and re-organise the course around student-led discussions. We would still cover the same material but students would lead each other through concepts, examples and discussion questions. My role reverted from being the ‘sage on the stage’ to a real ‘guide on the side’, jumping in to clarify, correct and extend discussions where necessary, but doing my best to stay out of the way of the real student learning that emerges from these small, motivated groups. It was a wonderful semester and all the students did well in the course and, I hope, enjoyed the two hours each day we would meet to talk and learn.

I discovered this week that I’ll have an opportunity to teach another small group – this time seven students – in the upcoming summer semester. As a result I’m returning to this student-led discussion format and putting the responsibility for learning clearly on the shoulders of the students in the class. I have made a couple of changes from last time around to overcome a couple of issues that did emerge – for example, I am teaching in a ‘normal’ fashion the first week of the course so as to get the core concepts and theories down pat – but other than that I am looking forward to a summer where, each afternoon, I’ll have a chance to talk society, culture, current affairs, politics and transnational issues with a small group of bright, engaged learners. What academic could ask for more?

The realities of the contemporary higher education business model means that small classes are not encouraged by administrators who are keen to maximise the return on the investment of time and capital in delivering face-to-face learning. The chance to teach small groups of undergraduates as I will this summer comes along only infrequently but, when it does, it is something to be embraced and enjoyed. Small classes almost always mean more individual attention from the professor, more opportunities to participate in class discussions, and greater opportunities to learn. A small undergraduate class might be somewhat of a rare occurrence on a modern campus but it is one that will continue to be embraced by professors seeking a return to a now near-vanished ideal of academia.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Turning Point & Padlet: Using Technology in Small Group Teaching

- Small Grants from Great Powers: Academic Integrity vs. Information Warfare

- Small Island Climate Diplomacy in the Maldives and Beyond

- The Virtue of Being Small: An Analysis of Luxembourg’s Defence Strategy

- Thomas Sankara: How the Leader of a Small African Country Left Such a Large Footprint

- The Venezuelan Crisis Spills Over Into a Small Island – Trinidad and Tobago