A Complex Dream or a Simple Reality? The Relationship between In-State Tuition Laws and College Enrollment of Undocumented Hispanic Students

Introduction

Since 2001, when Senator Orrin G. Hatch (R-Utah) and Senator Richard Durbin (D-Illinois) pioneered a bipartisan legislation of the Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors Act, also known as the DREAM Act, Congress has continued to debate over the passage of this immigration bill. Under the Act policy, undocumented immigrant youth, brought to the United States as children, can be legalized and eventually become U.S. citizens. As considerate as the Act appears, it has not been passed into law yet. Several versions of the bill have been written and rewritten to satisfy both the Senate and the House. In 2010, the bill passed the House but “fell victim to a GOP filibuster,” bringing final tally to 55 to 41 (Mascaro. L. & Oliphant, J., 2010). Apparently, five Democrats—Senators Max Baucus of Montana, Ben Nelson of Nebraska, Kay Hagan of North Carolina, Jon Tester of Montana, and Mark Pryor of Arkansas—sided with Republicans to oppose the bill, while Democrats received votes in favor of the bill from Senators Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, Robert Bennett of Utah, and Richard Lugar of Indiana (Herszenhorn, D., 2010). Although the Senate has killed the bill for the past ten years, there was another hope for its passage in January 2013, when both chambers of Congress reintroduced the DREAM Act after the President Obama’s Inauguration, but it failed again (Dreamact, 2009).

In support of the DREAM Act, this paper examines the bill by looking at arguments in favor of and against it in order to link it to similar state legislations, passed currently in fifteen states. Imitative of the bill, such legislations, the author believes, could provide evidence of whether the Act will be a success once it is enacted. The objective is to determine whether the DREAM Act has been carried out successfully on the state level and whether the United States can benefit from it at the federal level.

In the following sections, the author describes arguments from supporters and opponents of the DREAM Act, identifies the fifteen states that have passed laws imitating the DREAM Act, introduces the research question and a hypothesis, discusses previous studies on the topic, and explains how different this study is and why it is worth researching.

Dream Act: Support And Opposition

The Dream Act was initially introduced to directly solve a long-term problem—illegal immigration—and indirectly improve the national economy and college graduation rates throughout the country. Under the proposed Act, young people who came to the United States at age of fifteen or younger and who “have maintained good moral character” since their arrivals “qualify for conditional Permanent Resident status upon acceptance to college, graduation from a U.S. high school, or being awarded a GED in the US” (National Immigration Law Center, 2011). To obtain this conditional Permanent Resident status and eventually become eligible for U.S. citizenship, immigrants can either go to college or serve in the U.S. military. It is important to mention that not every single undocumented immigrant is qualified for this sort of amnesty. In addition to the age requirement, one must be present in the United States for at least five consecutive years prior to enactment of the bill (Dreamact, 2012).

As of March 2012, 11.7 million undocumented immigrants resided in the United States, whereas in 2000 the number was less than 8.5 million (Passel, J., Cohn, D., & Gonzalez-Barrera, A., 2013; Hoefer, M., Rytina, N. & Baker, B., 2012). In other words, almost twelve million undocumented immigrants have lived in the country, worked illegally, been speaking or learning to speak English, and been accustomed to American traditions and rules since the moment they entered the U.S. borders. Significantly, children of such immigrants might not even remember their native countries at all due to their young age. Considering the total of national population of 316,977,634, the number of illegal immigrants is high undoubtedly (U.S. Census, 2013).

Similarly, when it comes to graduation from post-secondary institutions, the numbers are worth mentioning as well. For example, the 2011 graduation rate for full-time undergraduate students who began their pursuit of a bachelor’s degree for the first time at a four-year institution in 2005 and completed the degree at that institution within six years was 59 percent (U.S. Department of Education, 2013). As of October 2012, of the sixty-three millions 20-34 year olds, only 18, 248,000 are enrolled in undergraduate or graduate institutions (U.S. Department of Education, 2013). Offering the opportunity to receive a higher education and to legalize the status of qualified undocumented youth, the bill, once enacted, could produce more college students, military recruits, and taxpayers all contributing to the prosperity of the United States. Yet it has been controversial over the past ten years.

Support

According to supporters, the DREAM Act offers great benefits, the most popular of which are described here. First, it can increase the pool of qualified military recruits (Garamone, J., 2010.). Able to speak English and their native language, young illegal immigrants have great potential as military recruits yet are prohibited from enlisting. Former West Point Professor Margaret Stock, referring to a Pentagon study that showed that legal immigrants “outperform” U.S. citizens, predicted that qualified individuals would do well once they are enlisted, and their participation “could help fill the recruitment gap” (Phelan, S., 2011). Second, the passage of the DREAM Act would help to reduce high school dropout rates and to increase the number of students to attend college. According to New York State Education Department, 74% of the high school students who started ninth grade in 2007 graduated in 2011. For the 2006 cohort, the rate was 73.4%, and for the 2003 cohort, the rate was 69.3% (Dunn, T., Burman, J. & Briggs, J., 2012). Although gradually increasing, these numbers suggest that the high school graduation rates still need to be improved, and as the supporters argue, the DREAM Act can help to do so. While illegal youngsters are permitted to go to high school, not all of them graduate because they are barred from applying to undergraduate programs and cannot get jobs due to the lack of legal documents. The DREAM Act would eliminate these barriers and motivate them to stay in high school and graduate. And finally, passing the DREAM Act into law would provide a boost to the U.S. economy. In particular, stimulating current undocumented young immigrants to obtain a higher education and enabling them to work legally, the Act would add $329 billion to the national economy by 2030 (Guzmán, J. & Jara, R., 2012). This number also includes future expenditures on services and goods by these immigrants. Consequently, the aforesaid military, educational, and economic advantages that the DREAM Act offers are strongly supported by and argued for by DREAM Act proponents.

Opposition

Opponents of the DREAM Act see the proposed bill from a different perspective, however. They believe that the bill will not fix the immigration system but rather worsen it by spurring a mass amnesty. Instead of punishing illegal immigrants in a form of deportation for either entering the United States without authorization or overstaying their visas without authorization, the bill proposes to reward them, opponents argue (McFadyen, J. 2013). Indeed, encouraging continued illegal immigration, it shall expand immigration gap because qualified undocumented students will eventually request legal residency for their relatives. Moreover, if the DREAM Act is passed into law, education spots will be taken away from American students and given to immigrants (Seitz-Wald, 2010; McFadyen, J. 2013). Meaning, native-born students will be cheated out of opportunities because they will face significant competition from immigrant students leading to a more competitive college application process and ultimately job market (Immigration Policy Center, 2010). More importantly, qualified immigrant students will be permitted to pay in-state tuitions, whereas U.S. born students will not be. This particularly seems to be unfair towards the natives since they will have to continue paying non-resident tuitions which are often two to three times more expensive than in-state tuitions (Gonzales, p.10, 2007). For instance, an undocumented student could pay only $780 a year at any of the California Community Colleges versus $4620 that a native citizen would pay for out-of-state fees for the same year (Undocumented Students, 2007, p.3). Without a doubt, opponents cannot ignore such a huge difference between in-state and out-of-state tuitions. In fact, it is the strongest argument the opposition makes, and it has been countlessly used to block the passage of the bill.

In-State Tuition For Undocumented Immigrants

Before getting into details of in-state tuition policies, it is essential to explain how the DREAM Act is relevant to this research and why the problem of illegal immigration is important to discuss. Since 2001, the DREAM Act has been attempted to pass at the federal level and has been numerously turned down. Because potential beneficiaries would be eligible for in-state tuitions, Steven Camarota (2010) demonstrated in his research on the impact of the DREAM Act that most of those who would qualify after the act is passed could be, indeed, expected to go to state schools (p. 3). In particular, he estimated that of the eligible 1,139 million illegal immigrants under the age of thirty-five, about “half a million” would enroll right away and the remaining half million later on (Camarota, 2010, p.4). While the destiny of the bill is unknown, some states have decided to take the issues of education and illegal immigration into their hands. California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Kansas, Maryland, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, Oregon, Texas, Utah, and Washington passed their own versions of the DREAM Act in different years (National Immigration Law Center, 2013). Attempting to expand college access to more individuals, these fifteen states permitted qualified undocumented students to pay lower tuition rates. It is crucial to look at each state individually to understand their lenient position on illegal immigrant youth. Given the large population of undocumented immigrants in 2011 in California (2,830,000), Texas (1,790,000), New York (630,000), Illinois (550,000), and in Washington (260,000), it is not surprising that these states decided to pass policies offering in-state tuitions (Hoefer, M., Rytina, N. & Baker, B., 2012). After all, the more individuals they attract to their colleges and universities, the more educated residents they would have. Moreover, the numbers of private and public colleges and universities could also be a reason for such policies (see Table 1).

Table 1 – Public and Private Colleges and Universities in Fifteen States

| STATE | Number of Public Colleges and Universities | Number of Private Colleges and Universities |

| California |

141 |

107 |

| Colorado |

28 |

15 |

| Connecticut |

18 |

13 |

| Illinois* |

59 |

62 |

| Kansas |

31 |

24 |

| Maryland |

29 |

17 |

| Minnesota |

41 |

32 |

| Nebraska* |

14 |

19 |

| New Mexico |

27 |

4 |

| New York* |

75 |

165 |

| Oklahoma |

27 |

14 |

| Oregon |

24 |

18 |

| Texas |

100 |

52 |

| Utah* |

9 |

14 |

| Washington |

43 |

18 |

* Number of private colleges exceeds the number of public in this state. The numbers represent four-year and two-year colleges and universities. Community colleges are excluded. Data is from http://www.collegecalc.org/

Table 1 compares the number of four-year and two-year public colleges and universities to the number of four-year and two-year private post-secondary institutions in the fifteen states. Evidently, except for Illinois, Nebraska, New York, and Utah, where the numbers of private colleges exceed the numbers of public colleges, the remaining eleven states that passed in-state tuition laws have relatively more public post-secondary institutions (see Table 1). The numbers of these institutions suggest that there is a need for more students to be enrolled in those states. Ostensibly, public colleges and universities are founded and operated by state governments. State tax revenues support educational quality and academic resources. Private institutions, in contrast, operate on revenues from tuitions, contributions from independent organizations, and on federal and private grants (Humphreys, D., n.d.). Thus, they do not depend on states for financial support.

Furthermore, discussing the problem of illegal immigration is important because various education and immigration policies “send mixed signals” to undocumented youth (Gonzales, R., 2007, p.2). On the one hand, undocumented students can be admitted to high school without even having a social security number. Indeed, the Fourteenth Amendment protects them from being denied access to public elementary and secondary education despite their illegal status. On the other hand, after undocumented students graduate from high school and apply to college, their illegal status gets in the way. Apparently, they do not have any access to federal and state student aid benefits, work-study programs, or scholarships (Muñoz, C., 2009, p.10). Excluded from the legal workforce, undocumented students have very slight chances of affording post-secondary education, nor could their families help them since they also work only illegally. For instance, illegal Mexican workers receive lower earnings than legal Mexicans because their educational attainment and English language proficiency are lower than legal immigrants’ (Rivera-Batiz, F., 1999, pp. 111-112). This suggests that once legalized, undocumented immigrants experience upward mobility, if not immediately than over some time (Gonzales, R., 2007, p.3). But before they become eligible to obtain legal status, if they even find legible grounds to claim permanent residency, illegal immigrants are isolated from the society they chose to live in.

Research Design

In this section, the author identifies independent and dependent variables, specifies which ethnic group of undocumented immigrants will be studied, and provides definitions for the most used words in the paper. With the independent variable—the in-state tuition laws—the author will measure whether it causes a change in the dependent variable—college enrollment. Looking at both variables separately will help to determine what relationship they have to each other. Moreover, according to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (2011), the majority of undocumented immigrants comes from Mexico – 6,800,000, followed by El Salvador – 660,000, Guatemala – 520,000, Honduras – 380,000, China – 280,000, Philippines – 270,000, Indian – 240,000, Korea – 230,000, Ecuador – 210,000, and Vietnam – 170,000 (Hoefer, M., Rytina, N., & Baker, B., 2012). Because of such a big difference in numbers between Mexico and the rest of the countries, the author focuses on Hispanic/Latino illegal immigrants. Concentrating on one ethnic group is sufficient to fulfill the objective of the paper and is easier in terms of collecting appropriate data.

Concepts

The author uses Jeffrey S. Passel and Paul Taylor’s definition of “Hispanic/Latino” which means a “member of an ethnic group that traces its roots to 20 Spanish-speaking nations from Latin America and Spain itself (but not Portugal or Portuguese-speaking Brazil)” (2009). Thus, the data collected for this research includes Mexicans, Dominicans, Salvadoran, Cuban, etc. Furthermore, undocumented immigrants, also called illegal or unauthorized aliens, in this paper are referred to as “all foreign-born non-citizens who are not legal residents” (Hoefer, M., Rytina, N. & Baker, B., 2012). Throughout the paper, these three terms are used interchangeably.

In addition, before looking at the methodology, it is vital to learn the difference between two terms: “permanent resident” and “adjustment of status.” According to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, a person can become a permanent resident (also known as a green card holder), either residing inside or outside the United States, through three main categories: employment, family, and refugee or asylee status (2013). There are also other programs, including Diversity Immigrant Visa Program, Legal Immigration Family Equity (LIFE) Act, Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) Status, Registry, Amerasian Child of a U.S. Citizen, American Indian Born in Canada, armed Forces Member, Cuban Native or Citizen, Diplomat (Section 13), Help HAITI Act of 2010, Haitian Refugee, Indochinese Parole Adjustment Act, Informant (S Nonimmigrant), Lautenberg Parolee, Nicaraguan and Central American Relief Act (NACARA), Victim of Trafficking (T Nonimmigrant), and Victim of Criminal Activity (U Nonimmigrant), that help to grant authorization to live and work in the United States on a permanent basis (2013).

Adjustment of Status is “the process by which an eligible individual already in the United States can get permanent resident status . . . without having to return to their home country to complete visa processing” (USCIS, 2011). In other words, once a person meets all required qualifications for a permanent residence in a particular category (e.g., employment, family, etc.), his or her immigration status can be changed “from nonimmigrant or parolee (temporary) to immigrant (permanent)” (USCIS, 2011). Examples of such individuals are undocumented immigrants, foreign students, refugees, and temporary workers.

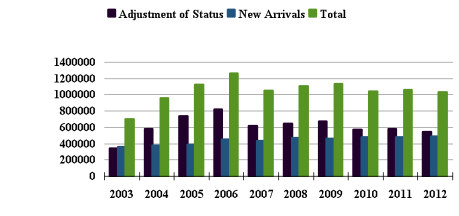

Table 2 shows the total number of legal permanent residents which consists of the number of new arrivals and the number of adjustment of status for each year from 2003 to 2012. The number of persons obtaining legal permanent resident status almost doubled from 703,542 in 2003 to 1,266,129 in 2006. In 2007, the number dropped to 1,052,415 and since then has been going up and down systematically. The last reported number for 2012 is 1,031,631 which is obviously higher than in 2003, only nine years ago. This suggests that although unsteadily, more immigrants become legal permanent residents every year. What is more crucial, however, is how those individuals obtain their green cards. Annually, the number of individuals who had adjustment of status prevails the number of individuals who received permanent status upon their arrivals to the United States. For example, in 2006, 1,266,129 immigrants became legal residents among them were 446,881 new arrivals and 819,248 adjustment of status. The same difference in numbers goes for each year. This implies that there are more people in the United States whose immigration status is illegal than new immigrants who come to the United States to receive green cards based on their already legal status.

Table 2 – Legal Permanent Residents

Source: Immigration Statistics: 2003-2012, http://www.dhs.gov/yearbook-

The relationship between in-state tuition laws and college enrollment of illegal immigrants has been already studied. Particularly, Lisa Dickson and Matea Pender (2013) tested the two variables, but their research was focused on the Texas state legislation H.B.1403 primarily. The researchers examined the effectiveness of the policy at the University of Texas (Austin), the University of Texas (Pan American), the University of Texas (San Antonio), Texas Tech University, and Texas A&M University, by analyzing the cost of attending each of these public colleges. The results showed that tuitions for non-citizens at the University of Texas (San Antonio) and the University of Texas (Pan American) were significantly lowered due to the Texas legislation. Another study to evaluate the effect of in-state tuition laws was conducted by Aimee Chin and Chinhui Juhn (2010). By comparing “outcomes in states that have the law to states that do not have the law,” they concluded that the laws had a positive impact only on older Mexican men (Chin, A. & Juhn, C., 2010, p. 3). The rest of their findings, however, demonstrated no significant effect on enrollment.

In this research, the author, offering a different approach, believes to find evidence suggestive of a positive impact of in-state tuition legislations on college enrollment of undocumented Hispanic students in each of the fifteen states. Given that there is an invariably significant proportion of illegal immigrants reside in the United States, knowing how many of them are already enrolled in public colleges and universities can help to examine the effects of the in-state tuition policies. Also, to determine how many of the immigrant students were undocumented, if not anymore, prior to the passage of the policies, the researcher investigates changes in the illegal immigrant population for the period of 1990 through 2013, which includes the years when the in-state tuition policies were passed. After all, half of current enrolled Hispanic students can be undocumented or all of them can be American citizens. Therefore, the author anticipates to find that after the laws became effective, the population of illegal immigrants decreased.

Research Question

This research is guided by the following question: what is the relationship between in-state tuition laws of the fifteen states and college enrollment rates in those states? The author expects to discover a positive correlation: evidence indicative that because of the laws, more Hispanic students go to college. Although previous researchers tested this hypothesis, the author believes that the usage of quantitative methodology in this study will provide robust results. Examining mostly secondary data, the researcher will compare outcomes of college enrollment in each of the fifteen states before and after those states passed their in-state tuition legislations and then will match them manually to changes in the population of illegal immigrants. Fulfilling the objective of the paper, the author approaches the research from a political perspective to explain what the results mean and what importance they might play in society as a whole.

Methods And Data Collection

In the following sections, the author analyzes each state individually and provides brief descriptions of in-state tuition policies. After collecting data from sources such as the Pew Research Center, National Immigration Law Center, the Texas Education Agency, and many official state government sites, the author created graphs to better demonstrate the findings. In the discussion of each state, two charts are presented (unless information was unavailable): one chart is to demonstrate college enrollment of Hispanic students in public colleges and universities in each state, and second chart is to display the population of undocumented immigrants in those states for the period of 1996 to 2012. Unfortunately, for the states of Texas, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Utah, and Washington, appropriate statistics were not available. Also, because Connecticut, Maryland, Minnesota, Oregon, and Colorado passed their in-state tuition laws recently, they were excluded from the research. Consequently, even though the author discusses each state in an alphabetical order, the conclusion of this study will be drawn based on the results from the remaining three states: California, Illinois, and New York.

A. California (2001)

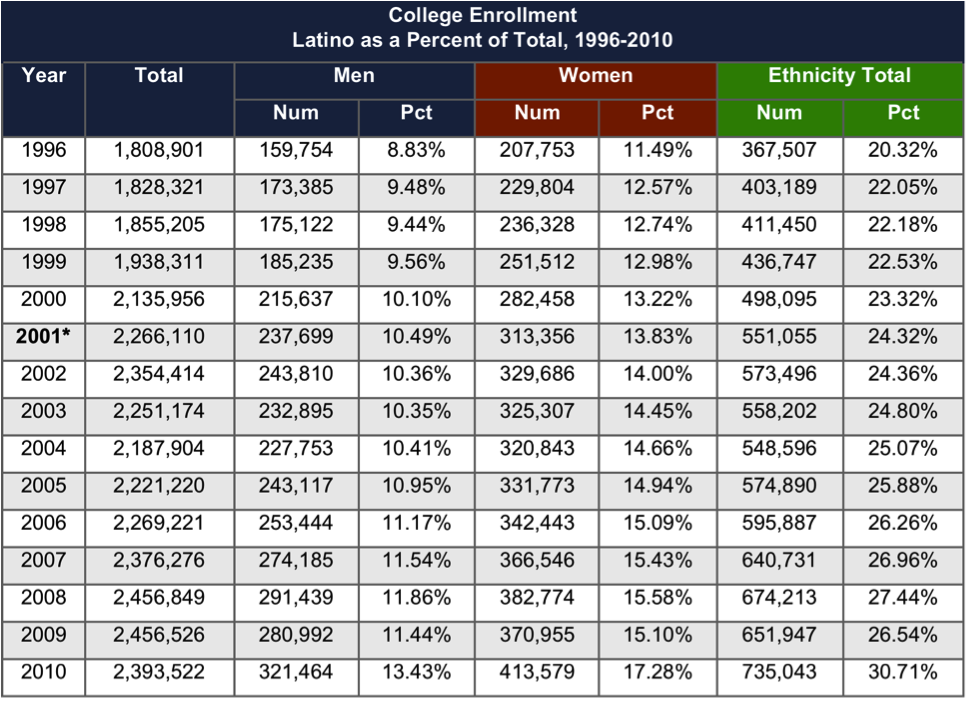

Allowing qualified undocumented students to pay in-state tuitions at California’s public colleges and universities, California passed its DREAM Act, also known as the California’s Assembly Bill 540, in 2001. What differs about this law is that it permits students without legal documents to apply for student financial aid benefits (Caitlin, E., 2013). For instance, at the University of California, Berkeley, about 250 students received grants or scholarships for 2012-2013. Using a report from the Campaign for College Opportunity, a bipartisan coalition, dedicated to ensuring that the next generation of Californians would have the opportunity to go to college, the author borrowed a graph from the Postsecondary Education Commission since it had already input the data that was needed (2011). The graph, shown as Table 3, demonstrates that since 1996 to 2010, the most recent years available, the number of Latino students has been overall gradually increasing by 8,261 – 61,348 students. In 2002, a year after the California’s DREAM Act was passed, the share of Latinos increased from 551,055 in 2001 to 573,496 in 2002, yet it dropped to 558,202 in 2003 and to 548,596 in 2004. As a result, because the number of Latino students has been raising yearly, there is no definite indicator that the California’s Assembly Bill 540 impacted college enrollments of Latinos.

Table 3 – Enrolment of Latinos in California Public Colleges and Universities

* Year when the California DREAM Act was passed.

This graph is borrowed from http://www.cpec.ca.gov/StudentData/EthSnapshotGraph.asp

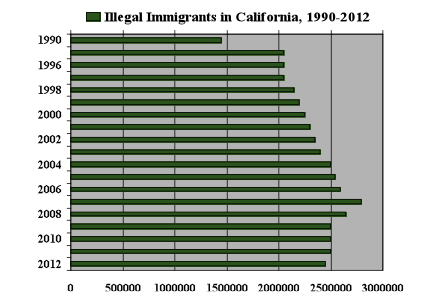

Moreover, according to the Pew Research Center, since 1990 the population of undocumented immigrants went up by 1,000. Although this number is not very high for the span of twenty-two years, it still exemplifies that the number of illegal immigrants in California has not been constant. Interestingly, when the California’s Assembly Bill 540 passed in 2001, the undocumented population kept increasing until 2007, the year when it reached the highest of 2,800,000, and since then began reducing yearly to 2,450,000 in 2012 (U.S. Unauthorized Immigration Population Trends, 1990-2012). Evidently, it took the law six years (from 2001 to 2007) to become effective in helping young illegal Hispanic students to go to college and legalize their status (see the below chart).

Source: Pew Research Hispanic Trends Project, http://www.pewhispanic.org/

B. Illinois (2003)

Passed in 2003, Illinois General Assembly Public Act 093-0738 allows undocumented students to be classified as Illinois residents to pay in-state tuition at state universities (Undocumented Student Criteria, 2013). Before the Act, higher education was not accessible to undocumented students, but since its implementation students who are not U.S. citizens or legal permanent residents can file an affidavit to indicate that they “will apply for legal residency as soon as they are eligible to do so” (Undocumented Student Criteria, 2013).

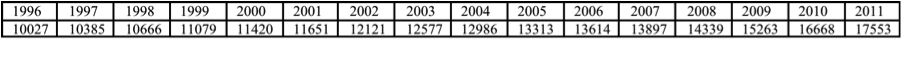

According to the Illinois Board of Higher Education, the number of Hispanic students enrolled in public colleges and universities in Illinois has been going up before and after the Act was enacted.[2] For instance, in 1996, 10,027 Hispanics were enrolled in public universities. Ten years later, there were 13,614. And as of 2011, 17,553 Latinos started college. More detailed analysis is shown in Table 4.

Table 4 – Enrollment of Hispanic Students in Public Colleges in Illinois, 1996-2011

* Year when the Illinois General Assembly Public Act 093-0738 was enacted.

These numbers do not include enrollments in community colleges, independent NFP institutions, Independent for-Profit Institutions, and out-of-state institutions. Source: http://www.ibhe.org/EnrollmentsDegrees/Search.aspx

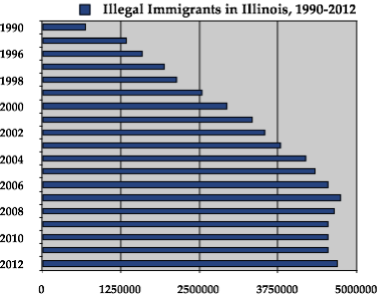

While the enrollment of Latino students has been growing, the population of illegal immigrants in Illinois experienced some changes as well. Significantly increasing by at least 250 individuals annually, the population continued with this pace even after Illinois enacted the Illinois General Assembly Public Act 093-0738. But in 2008, five years later, it went down to 4,650,000 and remained at 4,550,000 for the subsequent three years. In 2012, the populace of undocumented immigrants raised again to 4,700,000, almost reaching its peak in 2007 of 4,750,000.[3] More comprehensive analysis is presented in the “Illegal Immigrants in Illinois, 1990-2012” graph below.

Source: Pew Research Hispanic Trends Project, http://www.pewhispanic.org/

C. New York (2002)

New York signed into law S.B. 7784—Resident Tuition Policy—in August 2002. Based on the content of the law, illegal immigrant students “who have attended two years of high school or graduated high school in New York (or received GED in New York)” are permitted to make payments for State University of New York (SUNY) and City University of New York (CUNY) tuitions at the same rate imposed on New York residents (Hesketh, L., 2002). In return, they have to prove that they applied for legal status.

Over the period of 2000-2010, the New York City’s Latino population increased by 175,000. The number of students receiving an Associate degree alone grew rapidly. More clear increases in overall enrollment rates of Hispanics is evident from 2003, the year after New York passed the Resident Tuition Policy, to 2009. In 2010, the number went down.[4] More detailed analysis can be found here.

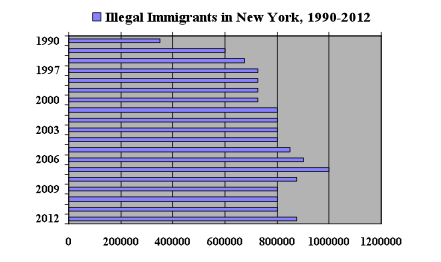

Furthermore, even though data demonstrating college enrollment of Hispanic/Latino students at CUNY is suggestive of positive effects of the in-state tuition law, the author also investigated variations in illegal immigrant population in New York. Similar to California and Illinois, the population of undocumented immigrants in New York encountered interesting changes. For example, starting in 1990, more illegal immigrants came to New York every succeeding year until 2008, when the number of the undocumented dropped to 875,000 from 1,000,000 in 2007. Then it went up again to 800,000 in 2009 and remained constant for another two years, yet in 2012 it rose to 875,000. Important to mention that after 2002 there were no rapid declines in population for six years.[5] The below chart shows more details.

Source: Pew Research Hispanic Trends Project, http://www.pewhispanic.

D. Texas (2001)

Texas enacted and made immediately effective HB 1403, which authorized certain individuals to qualify as residents of this state for purposes of providing access to in-state tuition rates at Texas public institutions of higher education and state financial aid paying tuition at the rate provided to residents of this state, in 2001 (“Residency and In-State Tuition,” 2008). To qualify, undocumented students have to be reside in Texas for at least the three years while attending high school in Texas, graduate from a public or private high school (or received a GED in Texas), and provide their institutions with a signed affidavit indicating they would apply for permanent resident status (“Residency and In-State Tuition,” 2008)

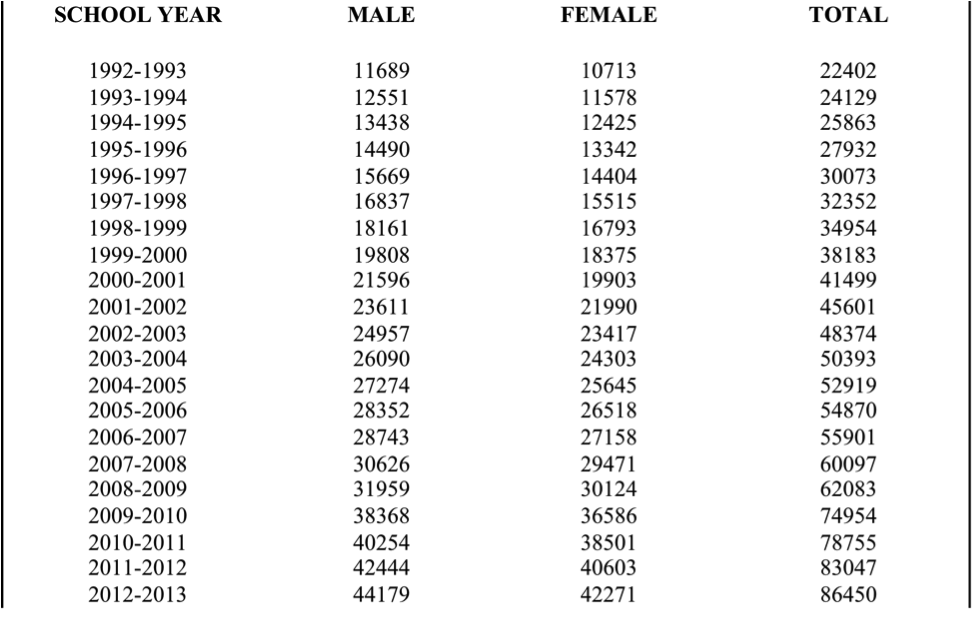

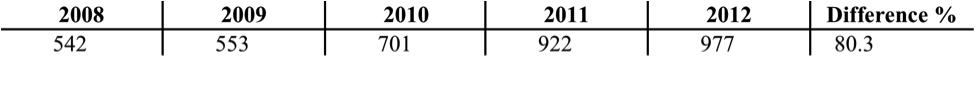

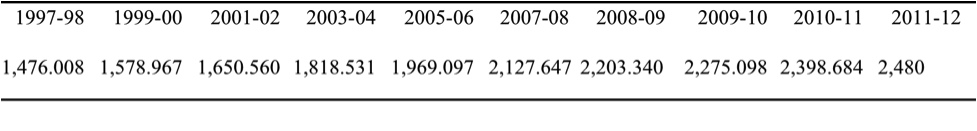

Unfortunately, finding statistics on college enrollment of Latino students in Texas was unsuccessful. Table 6 illustrates public high school enrollment data for young Hispanics for the period of 1997-2012. According to the Texas Education Agency, since 1997 to 2012, more Hispanic children enroll each year to Texas public schools. Within fourteen years, the enrollment rose by 1, 004 from 1,476 in 1997-1998 to 2,480 in 2011-2012 (see figure 6).[6] Although this information is included, it cannot be used for testing the hypothesis because it does not guarantee how many of these Hispanics applied or are planning to apply in the future to college.

Table 6 – Enrollment of Hispanics in Texas Public Schools, 1997 – 2012

Source: http://www.tea.state.tx.us/acctres/enroll_index.html.

Source: http://www.tea.state.tx.us/acctres/enroll_index.html.

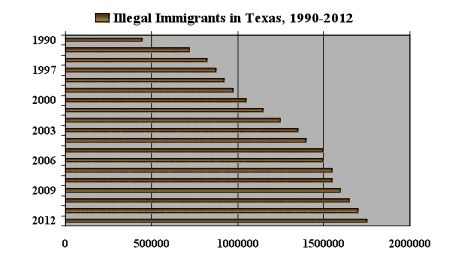

In spite of ruling out the aforesaid data, the author still created a chart to demonstrate what was found on the population of illegal immigrants in Texas, from 1990 to 2012. Since 1990, the population has been growing continuously. Only in 2004-2005 and 2007-2008, the numbers did not vary. But overall, there has been an increase of 1, 300,000 for the period of twenty-two years, from 450,000 in 1990 to 1,750,000 in 2012.

Source: Pew Research Hispanic Trends Project, http://www.pewhispanic.org/

E. Colorado (2013)

In 2013, Colorado joined the support-the DREAM-Act states by signing into law the Colorado’s ASSET bill — legislation that guarantees “fair tuition rates for students who attend at least three years of high school in Colorado, regardless of their immigration status” (Saccone, M., 2013). To qualify for the in-state tuition, students must graduate from a Colorado high school or obtain a general education diploma, and must declare their intention to pursue legal immigration status (Cotton, A., 2013). Though this legislation does not differ in its intent to make post-secondary education accessible to undocumented young immigrants, the Colorado’s ASSET bill has been attempted to pass for the past ten years, finally succeeding at its seventh attempt in 2013. Because of its newness, however, the state of Colorado had to be excluded from the research.

F. Connecticut (2011)

In 2011, Connecticut passed a bill “providing in-state tuition at public college and universities for undocumented students” (Thomas, J., 2011). Connecticut joined the other states in allowing young individuals without legal documents to enroll in public post-secondary institutions. As a result of its recent passage, however, Connecticut cannot be used in the research. Additionally, no data is available to show the changes in the undocumented immigrant populace in Connecticut over time.

G. Kansas (2004)

The state of Kansas enacted Kansas HB 2145 in 2004 and authorized undocumented residents “who have attended a Kansas high school or who have lived in Kansas for three years and are a student at a postsecondary education institution to be considered residents of the state for the purpose of tuition and fees” (Kansas H.B. 2145, 2004). As a consequence, young persons without lawful immigration status can go to college and pay resident tuition fees.

Measuring the effectiveness of Kansas HB 2145 was unsuccessful because no data on enrollment of Hispanic students in Kansas public colleges and universities is available. The author did, however, look at enrollment rates of Latinos in public schools to examine any changes in Hispanic population in Kansas for the past twenty-two years. Based on the Kansas Department of Education K-12 Reports, the number of Hispanic students have gone up annually.[7] Similar to the Texas public school enrollment rates, the number of Hispanics in Kansas continues to grow.

Table 7 – Number of Hispanic Students in Kansas Public Schools, 1992-2013

Source: http://svapp15586.ksde.org/k12/state_reports.aspx

H. Maryland (2001)

To allow illegal immigrants to claim state residency and pay in-state tuition, Maryland “became the first to adopt such a law by popular vote” (Rerez-Pena, R., 2012). Joining other aforesaid states, the state of Maryland gives young people access for applying to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services agency for formal recognition under the policy (Rerez-Pena, R., 2012). Analyzing whether the law is effective is not possible at the moment because it has been only two years since its passage, and there was no data found to indicate illegal immigrant population in Maryland. For these reasons, the state of Maryland is eliminated from the research.

I. Minnesota (2013)

In May 2013, the MN Dream Act, also known as the Prosperity Act, was signed into law by the Minnesota state legislature. Under this Act, students without legal documents who 1) have attended a Minnesota high school for at least three years, 2) graduated from a Minnesota high school or earned a GED in Minnesota, 3) registered with the U.S. Selective Service (only for males 18 – 25 years old), and 4) provide proof that they have applied for lawful immigration status, are eligible for in-state tuition rates and able apply for state financial aid (Ebner, T., 2013). The MN Dream Act application must be resubmitted every academic year a student is enrolled in college. Minnesota is also excluded from the research due to the lack of data.

J. Nebraska (2006)

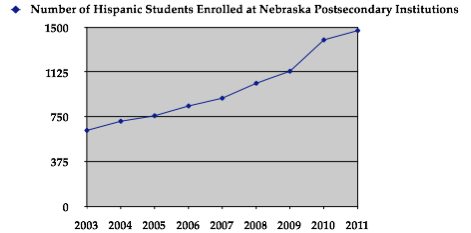

Since 2006, Nebraska allows undocumented students to pay in-state tuition at any public state college if such students, after providing proof of residence in Nebraska for at least three years before graduating from a Nebraska high school or obtaining a GED, present a signed affidavit affirming their intention to become a permanent resident (“Undocumented Student Bill,” 2013). This lenient attitude towards illegal residents is due to the passage of a legislation known as LB 239. Evidently, the content of the law is equivalent to the contents of the other states’ laws, but whether LB 239 is successful at the state level is impossible to determine as a consequence of data deficiency. In particular, the author could not obtain statistics on the population of undocumented immigrants in Nebraska. Without this information, the effectiveness of LB 239I cannot be determined. Regardless, the author inserted a chart, borrowed from the official Nebraska Government website, to demonstrate variations in enrollment rates of Hispanic students in Nebraska public colleges before and after 2006. As illustrated in Table 8, from 2003 to 2011, the number of Hispanics rose by 836; there is no drastic jump after 2006: 2003 – 635, 2004 – 712, 2005 – 758, 2006 – 840, 2007 – 905, 2008 – 1030, 2009 – 1131, 2010 – 1393, 2011 – 1471.[8]

Table 8 – Hispanic Students Enrolled at Nebraska Public Colleges, 2003-2011

Source: http://www.ccpe.state.ne.us/

K. New Mexico (2005)

According to New Mexico Legislature, on March 15, 2005, New Mexico enacted SB 582 to let illegal immigrants to access in-state tuition and state-funded financial aid. New Mexico promised to treat all its residents, legal and illegal, equally when it comes to post-secondary education. After attending a “secondary educational institution in New Mexico for at least one year” and either graduating from a New Mexico high school or receiving “a general educational development certificate in New Mexico,” young individuals without lawful documents are welcomed to apply to college (SB0582, 2013).

Alas, attaining statistics to indicate college enrollment rates of Latino students in New Mexico public colleges and universities and to specify how many young illegal immigrants in New Mexico have had their status adjusted as a result of SB 582 was unsuccessful. Thus, New Mexico is not used in the research.

L. Oklahoma (2003)

When enacted in 2003, the Oklahoma DREAM Act stated that undocumented youth in the state was to be eligible for in-state tuition at public institutions of higher education. Yet in 2008, Oklahoma amended the Act by passing H.B. 1804, “a bill that ended its in-state tuition benefit, including financial aid, for undocumented students” (“Oklahoma,” 2013). Instead, it permitted the Oklahoma State Regents to grant in-state tuition rates to undocumented students who meet Oklahoma’s statutory requirements. Even though young unlawful immigrants in Oklahoma are not banned from applying to colleges and for scholarships, public colleges in Oklahoma have different policies which might create obstacles (“Oklahoma,” 2013).

Oklahoma is eliminated from the research for the following two reasons: 1) lack of data on enrollment rates of Hispanic students in Oklahoma public post-secondary institutions and 2) inadequate statistics on illegal immigrant population in Oklahoma. The only facts regarding college enrollment of Hispanics that were found are represented in Table 9. They are, however, a partial representation of enrollment rates (from 2008 to 2012 only) and, therefore, not utilized.

Table 9 – Enrollment of Hispanics in University of Central Oklahoma

Source: http://www.uco.edu/academic-affairs/ir/files/demographic-book/2012-Spring-Demo-Book.pdf

M. Oregon (2013)

As of July 1, 2013, Oregon granted in-state tuition and public education to its undocumented population by passing HB 2787. Those who “studied in an Oregon high school for at least three years,” graduated, and intended to become lawful permanent residents or U.S. citizens, can enroll in public colleges and universities while paying in-state tuition fees (Hovde, E., 2013). Although this law does not differ from the in-state tuition laws passed by other states, it cannot be investigated because of its recent execution. Also, the undocumented immigrant populace in Oregon is unknown. Consequently, the state of Oregon is not included in the research.

N. Utah (2002)

The Utah Legislature passed House Bill 144, permitting undocumented students to qualify for resident tuition rates at Utah’s public colleges and universities, in 2002 (H.B. 144, 2007). To qualify for in-state tuition fees, illegal students must meet the following four basic requirements: 1) attend a Utah high school for three or more years; 2) graduate from a Utah high school or receive the equivalent of a high school diploma in this state; 3) register as an entering student at an institution of higher education; 4) file an affidavit with the college or university they apply to stating that they filed, or will file, to have their immigrant status legalized his immigration status.

Statistics showing the enrollment rates of Hispanic students in Utah public colleges and universities since 2002 and demonstrating how many illegal immigrants have been living in Oregon for the past twenty years were not found. Therefore, Oregon is excluded from the research.

O. Washington (2003)

In 2003, Washington granted in-state tuition to illegal students at public universities in the state by passing a law referred to as policy 1079. Even though this law does not qualify students for federal or state financial aid, it helps students without a lawful status who “have graduated from a Washington high school and have lived in the state for at least three years” to become qualified for in-state tuition at public institutions, rather than paying non-resident tuition (“In-State Tuition,”2012). Like the previously mentioned states, Washington requires from undocumented students to graduate from a Washington State high school while living in the United States for at least three years or to complete a GED and reside in Washington for three years prior to receiving it (“In-State Tuition,” 2012). Washington is also excluded from the research due to the lack of appropriate data.

Results And Discussion

Prior to starting the research, the author intended to examine fifteen states that have passed in-state tuition laws granting young undocumented immigrants access to post-secondary education. During the step of collecting and analyzing data, however, the author discovered that the relationship between the two variables—in-state tuition policies and college enrollment rates of Hispanic/Latino students—could be investigated based only on three states: California, Illinois, and New York. In particular, because Connecticut and Maryland passed their in-state tuition laws in 2011 and Minnesota, Oregon, and Colorado followed their steps in 2013, these states had to be excluded from the research. Furthermore, because the researcher specifically looked for annual reports on college enrollment of one particular race in public colleges and universities, such information was unobtainable for the following states: Texas, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Utah, and Washington. Therefore, they were eliminated from the research as well. Focusing primarily on California, Illinois, New York, and Texas, the author obtained statistics on the population of undocumented immigrants for only the first three states, ruling Texas out. Insufficiency of reliable sources to track the population of illegal immigrants in Texas was a must. Without this information, any finding for the state of Texas alone would be incomplete.

Examining in-state tuition laws in California, Illinois, and New York, the author did not find strong evidence suggestive of the laws’ impact on college enrollment of undocumented Hispanic students. Even though there were increases in enrollment rates of Latino students in each of the three states since 1996 to 2010, no rapid or substantial growth after the implementation of the laws was discovered to indicate that more Hispanic students enrolled in public post-secondary institutions as a result of the laws. After all, the author hypothesized that most young illegal Latinos would apply to public colleges and universities after the implementation of laws, demonstrating a clear increase in college enrollment among Hispanics, but no such confirmation was found.

Moreover, investigating any changes in the population of illegal immigrants in California, New York, and Illinois during the period of 1990-2012, the author expected to find declines in undocumented residents after the policies were enforced, but the expectations were not met. For example, while in California, it took the law six years (from 2001 to 2007) to become effective in helping young illegal Hispanic students to go to college and legalize their status, Illinois’ illegal population continued to increase by approximately 250 individuals annually until 2008, it dropped and remained unchanged for three years raising again in 2012. Similarly, the undocumented population of New York declined in 2009 and stayed fixed until 2012, when it went up again. These variations can suggest several results, including an expansion of present Hispanic families or increase in arrivals of Latino immigrants. But they can also indicate that the more young illegal Hispanics go to college, the fewer of them remain without legal documents, as the author believed. Of course, it is crucial to note that while the policies do not guarantee to legalize qualified undocumented immigrants after they get admitted to college, they do, however, imply this guarantee because even if such immigrants are allowed to pay in-state tuition fees, they are unauthorized to work. Obviously, the laws cannot enable undocumented students to enroll if those students will not be able to afford even in-state tuitions. Otherwise, it is counterproductive. And finally, illegal immigrants have to provide proof that they pursue permanent resident status as one of the requirements for admission.

Given all that, there is no concrete evidence confirming the hypothesis that the in-state tuition policies have positive effects on college enrollment of illegal Hispanic students. Although the enrollment rates increased and the population of illegal immigrants decreased years after the policies were enacted, they also experience the same changes before the enactments. As a consequence, the hypothesis was not supported.

Conclusion And Implications

Because the author was unable to find all appropriate data to test the hypothesis, more studies can be done in the future. In particular, studying the relationship between in-state tuition policies and college enrollment of undocumented Hispanic students is important for the following reasons. First, according to the U.S. Department of Education, the high school completion rates have not been improving for years (2013). Second, since 1920, the percentage of persons age twenty-five and over who obtained a Bachelor’s or higher degree has not reached higher than 30.9 for the past ninety-two years (U.S. Department of Education, 2012). Although, of course, more people receive degrees from postsecondary institutions over time, the graduation rates are still not impressive. And third, as of September 23, 2013, 11.7 illegal immigrants live in the United States (Preston, J., 2013). Allowing at least a quarter of that number to go to college can only benefit the country as a whole. Consequently, if future researchers find the data that was missing in this research and follow the same methodology, they might reach different results. In that case, confirming that in-state tuition laws have a positive effect on college enrollment rates of undocumented Latino students, their findings, like the earlier findings of Lisa Dickson and Matea Pender (2013) and Aimee Chin and Chinhui Juhn (2010), might provide evidence that in-state tuition policies in the fifteen states help undocumented youth in those states to enroll and perhaps encourage other states to pass similar laws. Ultimately, passing the DREAM Act at the federal level is not necessary if all states pass their legislations at the state level.

For years, federal immigration policy discussions have been mainly regarding comprehensive immigration reform legislation, yet chances for its success have remained uncertain. Whether the DREAM Act will be passed in the future is unknown at this time, but young undocumented immigrants residing in California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Kansas, Maryland, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, Oregon, Texas, Utah, and Washington can benefit from the states’ policies. Although this research does not provide strong support for this claim, without a doubt, the presence of such policies is better than their absence. After all, even if only one illegal immigrant goes to college under in-state tuition policy, it is still worth having the policy.

References

Adjustment of status (2011, March 30). USCIS. Retrieved on October 19, 2013, from http://www.uscis.gov/portal/site/uscis/menuitem.eb1d4c2a3e5b9ac89243c6a7543f6d1a/vgnextoid=2da73a4107083210VgnVCM100000082ca60aRCRD&vgnextchannel=2da73a4107083210VgnVCM100000082ca60aRCRD

Baum, S., & Flores, S. M. (2011). Higher education and children in immigrant families. Future Of Children, 21(1), 171-193. Retrieved on October 10, 2013, from http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/41229016?uid=3739832&uid=2&uid=4&uid=3739256&sid=21102786508311

Caitlin, E. (2013). Immigration debate: Tuition breaks go largely unclaimed. Politico. Retrieved on November 1, 2013, from http://www.politico.com/story/2013/07/an-in-state-tuition-deal-that-is-largely-unclaimed-93795.html#ixzz2kkpYrUXW

Camarota, S. (2010, November). Estimating the impact of the DREAM Act. Center for Immigration Studies. Retrieved on October 29, 2013, from http://www.cis.org/dream-act-cost

Chin, A., & Juhn, C. (2010, April). Does reducing college costs improve educational outcomes for undocumented immigrants? Evidence from state laws permitting undocumented immigrants to pay in-state tuition at state colleges and universities. National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved on October 10,2013, from http://www.uh.edu/~achin/research/w15932.pdf

Cotton, A. (2013). Colorado governor signs bill for illegal immigrants’ in-state tuition. The Denver Post. Retrieved on November 21, 2013, from http://www.denverpost.com/ci_23133446/gov-signs-state-tuition-bill-undocumented-colorado-students

Dickson, L., & Pender, M. (2013, December). Do in-state tuition benefits affect the enrollment of non-citizens? Evidence from universities in Texas. Economics of Education Review, Vol. 37, 126-137. Retrieved on October 20, 2013, from http://www.sciencedirect.com.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/science/article/pii/S0272775713001088#

Dowd, A., & Coury, T. (2006). The effect of loans on the persistence and attainment of community college students. Research In Higher Education, 47(1), 33-62. Retrieved on October 10, 2013, from http://ehis.ebscohost.com.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=11&sid=4151ccd6-6b1f-4502-8cb2-a7816fdbc6c9%40sessionmgr198&hid=6

DREAMACT (2012). Overview of the DREAM act. Retrieved on October 25, 2013, from http://www.dreamact2013.com/

Dunn, T., Burman, J. & Briggs, J. (2012, June 11). Education department releases high school graduation rated; overall rates improve slightly, but are still too low for our students to be competitive. New York State Education Department. Retrieved on October 17, 2013, from http://www.oms.nysed.gov/press/GraduationRates2012OverallImproveSlightlyButStillTooLow.html

Gildersleeve, R., & Hernandez, S. (2012). Producing (im)possible peoples: policy discourse analysis, in-state resident tuition and undocumented students in American higher education. International Journal Of Multicultural Education, 14(2),1-19. Retrieved on October 19, 2013, from http://ehis.ebscohost.com.ez.lib. jjay.cuny.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=4151ccd6-6b1f-4502-8cb2-a7816fdbc6c9%40sessionmgr198&vid=13&hid=6

Gilroy, M. (2009). Battle continues over in-state tuition for illegal immigrants. Quick Review, 74 (8), 16-20. Retrieved on October 19, 2013, from http://ehis.ebscohost.com.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=15&sid=4151ccd6-6b1f-4502-8cb2-a7816fdbc6c9%40sessionmgr198&hid=104

Gonzales, R. (2007). Wasted talent and broken dreams: the lost potential of undocumented students. Immigration Policy in Focus, V.5 (13). Immigration Policy Center. Retrieved on October 14, 2013, from http://www.coloradoimmigrant.org/downloads/Wasted%20Talent%20and%20Broken%20Dreams:%20The%20Lost%20Potential%20of%20Undocumented%20Students.pdf

Guzmán, J. & Jara, R. (2012, October 1). Infographic: How the DREAM Act helps the economy. Center for American Progress. Retrieved on October 27, 2013, from http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/immigration/news/2012/10/01/39659/infographic-how-the-dream-act-helps-the-economy/

Hao, L., & Pong S-L. (2008, November). The role of school in the upward mobility of disadvantaged immigrants’ children. American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 620, pp. 62-89. Retrieved on October 18, 2013, from http://www.jstor.org.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/stable/pdfplus/40375811.pdf?acceptTC=true& accept TC=true&jpdConfirm=true

Herszenhorn, D. (2010, December 18). Senate blocks bill for young illegal immigrants. Politics. The New York Times. Retrieved on October 23, 2013, from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/19/us/politics/19immig.html

Hesketh, L. (2002). New York S.B. 7784. The Education Commission of the States. Retrieved on November 23, 2013, from http://www.ecs.org/ecs/ecscat.nsf/5741e7f457e2861586256ae900595a76/d21070d899882da987256c130056a0e9?OpenDocument

Hoefer, M., Rytina, N., & Baker, B. (2012, March). Estimates of the unauthorized immigrant population residing in the United States: January 2011. U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved on October 29, 2013, from https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/ois_ill_pe_2011.pdf

Hovde, E. (2013, March 30). Our undocumented students deserve tuition equity. Oregonian Media Group. Retrieved on November 22, 2013, from http://www.oregonlive.com/hovde/index.ssf/2013/03/elizabeth_hovde_our_undocument.html

In-State Tuition (2012). Washington Student Achievement Council. Retrieved on November 20,2013, from http://www.wsac.wa.gov/PayingForCollege/FinancialAid/FAQ/Undocumented

Joaquin, L. (2013, May). Basic facts about in-state tuition for undocumented immigrant students. National Immigration Law Center. Retrieved on October 18, 2013, from http://www.nilc.org/basic-facts-instate.html

Kansas H.B. 2145 (2004). Education Commission of the States. Retrieved on November 21, 2013, from http://www.ecs.org/ecs/ecscat.nsf/1bfe154f4fe6a8cb87257a770050df06/e895b4f016be681887256eb3007e5eae?OpenDocument

Kasinitz, P. (2008, November). Becoming American, becoming minority, getting ahead: The role of racial and ethnic status in the upward mobility of the children of immigrants. American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 620 (1), pp. 253-269. Retrieved on October 10, 2013, from http://ann.sagepub.com.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/content/620/1/253.full.pdf+html

Kaushal, N. (2008). In-state tuition for the undocumented: Education effects on Mexican young adults. Journal Of Policy Analysis & Management, 27(4), 771-792. Retrieved on October 18, 2013, from http://ehis.ebscohost.com.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=4&sid=9d4dfbca-33e3-44dc-9b38-0d3d63d21c3e%40sessionmgr11&hid=6

Mascaro, L., & Oliphant, J. (2010, December 2010). Dream Act’s failure in Senate derails immigration agenda. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved on October 18, 2013, from http://articles.latimes.com/2010/dec/19/nation/la-na-dream-act-20101219

McFadyen, J. (2013). Opposition to the DREAM Act. Immigration Law and Policy. Retrieved on October 27, 2013, from http://immigration.about.com/od/immigrationlawandpolicy/a/Oppose_DREAMAct.htm

Montgomery, J. (2011). Laws on immigrant tuition vary. Indiana Lawyer, 22(19), 8-10. Retrieved on October 18, 2013, from http://ehis.ebscohost.com.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=14&sid=4151ccd6-6b1f-4502-8cb2-a7816fdbc6c9%40sessionmgr198&hid=104

National Immigration Law Center (2011, May). DREAM Act: Summary. Retrieved on October 23, 20103, from http://nilc.org/dreamsummary.html

Oas, D. (2010-2011). Immigration and higher education: The debate over in-state tuition. Law Journal Library. Retrieved on October 20, 2013, from http://www.heinonline.org.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/HOL/Page?page=877&handle=hein.journals%2fumkc79&collection=journals#908

“Oklahoma” (2013). Dream Activist. Retrieved on November 25, 2013, from http://www.dreamactivist.org/regions/region-6/oklahoma/

Other ways to get a green card (2013, April 16). USCIS. Retrieved on October 19, 2013, from http://www.uscis.gov/portal/site/uscis/menuitem.eb1d4c2a3e5b9ac89243c6a7543f6d1a/?vgnextoid=5a97a6c515083210VgnVCM100000082ca60aRCRD&vgnextchannel=5a97a6c515083210VgnVCM100000082ca60aRCRD

Passel, J., Cohn, D., & Gonzalez-Barrera, A. (2013, September 23). Population Decline of Unauthorized Immigrants Stalls, May Have Reversed. Pew Research Hispanic Trends Project. Retrieved on October 25, 2013, from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2013/09/23/population-decline-of-unauthorized-immigrants-stalls-may-have-reversed/

Passel, J.& Taylor, P. (2009, May 28). Who’s Hispanic? Pew Research Hispanic Trends Project.Retrieved on October 27, 2013, from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2009/05/28/whos-hispanic/

Pérez, P. A. (2010). College choice process of Latino undocumented students: Implications for recruitment and retention. Journal of College Admission, (206), 21-25. Retrieved on October 20, 2013, from http://ehis.ebscohost.com.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=4&sid=9d4dfbca-33e3-44dc-9b38-0d3d63d21c3e%40sessionmgr11&hid=102

Rerez-Pena, R. (2012, November 19). Immigrants to Pay Tuition at Rate Set for Residents. The New York Times. Retrieved on November 17, 2013, from http://www.nytimes.com /2012/11/20/us/illegal-immigrants-to-pay-in-state-tuition-at-mass-state-colleges.html?_r=0

Phelan, S. (2011, June 27). DREAM Act would reduce deficit, strengthen military…and perhaps save the world. San Francisco Bay Guardian Online. Retrieved on October 27,2013, from http://www.sfbg.com/politics/2011/06/27/dream-act-would-reduce-deficit-strengthen-militaryand-perhaps-save-world

Postsecondary Education Report (2011). California Postsecondary Education Commission.Retrieved on November 25, 2013, from http://www.cpec.ca.gov/StudentData/Eth SnapshotGraph.asp)

Preston, J. (2013, September 23). Number of illegal immigrants in U.S. may be on rise again,estimates say. The New York Times. Retrieved on December 10, 2013, from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/24/us/immigrant-population-shows-signs-of-growth-estimates-show.html

2013 Report on State Immigration Laws (Jan.-June). (2013, September). National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved on October 18, 2013, from http://www.ncsl.org/research/immigration/immgration-report-august-2013.aspx

Residency and In-State Tuition (2008). Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board. Retrieved on November 24, 2013, from http://www.thecb.state.tx.us/reports /PDF/1528.PDF

Rivera-Batiz, F. (1999, February). Undocumented workers in the labor market: An analysis of the earnings of legal and illegal Mexican immigrants in the United States. Journal of Population Economics, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 91-116. Retrieved on November 17, 2013, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20007616

Saccone, M. (2013, April 29). Udall: Signing of ASSET bill ensures all Coloradans have access to jobs, higher education. Mark Udall Senate. Retrieved on November 23, 2013, from http://www.markudall.senate.gov/?p=press_release&id=3376SB0582 (2013). The New Mexico Legislature. Retrieved on November 25, 2013, from http:// www.nmlegis.gov/Sessions/05%20Regular/final/SB0582.pdf

Seitz-Wald, A. (2010, December 10). Rep. Rohrabacher suggests white people will‘lose our freedom’ if the DREAM Act passes. ThinkProgress. Retrieved on October 10, 2013, from http://thinkprogress.org/politics/ 2010/12/10/134524/rohrabacher-dream-white-people/

Spakovsky, H., & Stimson, C. (2011, November 22). Providing in-state tuition for illegal aliens: A violation of federal law. The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved on October 18, 2013, from, http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2011/11/providing-in-state-tuition-for-illegal-aliens-a-violation-of-federal-law

State Level Dream Acts (2012, December 19). VisaNow. Retrieved on October 14, 2013, from http://www.visanow.com/state-level-dream-acts

Stewart, J., & Quinn, T. (2012). To include or exclude: A comparative study of state laws on in-state tuition for undocumented students in the United States. Texas Hispanic Journal of Law & Policy, 18(1), 1-47. Retrieved on October 18, 2013, from http:// ehis.ebscohost.com.ez.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=9&sid=489a627d-ce5d-487e-a543-a26203498ad1%40sessionmgr110&hid=115

Thomas, J. (2011, May 24). In-state tuition for undocumented students headed to Malloy’s desk. The CT Mirror. Retrieved on November 25, 2013, from http://www.ctmirror.org/story/2011/05/24/state-tuition-undocumented-students-headed-malloys-desk

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2013). The Condition of Education 2013 (NCES 2013-037), Institutional Retention and Graduation Rates for Undergraduate Students. Retrieved on October 25, 2013, from http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=40

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2013). The Condition of Education 2013 (NCES 2013-037), Status Dropout Rates. Retrieved on December 9, 2013, from http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=16

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (2012). Percentage of persons age 25 and over with high school completion or higher and a bachelor’s or higher degree, by race/ethnicity and sex: Selected years, 1910 through 2012. Retrieved on December 9, 2013, from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d12/tables/dt12_008.asp

U.S. Census (2013, October 31). U.S. and world population clock. Retrieved on October 31, 2013, from http://www.census.gov/popclock/

Undocumented Student Criteria (2013). Northern Illinois University. Retrieved on November 24, 2013, from http://www.niu.edu/chance/admissions/undocumented_student /index.shtml

U.S. Unauthorized Immigration Population Trends, 1990-2012 (2013, September 23). Pew Research Hispanic Trends Project. Retrieved on November 17, 2013, from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2013/09/23/unauthorized-trends/#All

Undocumented Students (2007). UCLA Center for Labor Research and Education. Retrieved on October 17, 2013, from http://www.labor.ucla.edu/publications/reports/Undocumented-Students.pdf

“Undocumented Student Bill” (2013). Northeast Community College. Retrieved on November 23, 2013, fromhttp://www.northeast.edu/admissions/pdfs

[1] Source: http://www.cpec.ca.gov/StudentData/EthSnapshotMenu.asp.

[3] More comprehensive analysis is presented in the “Illegal Immigrants in Illinois, 1990-2012” can be found here in Pew Research Hispanic Trends Project.

[4] More detailed analysis can be found here: http://www.cuny.edu.

[5] Source: Pew Research Hispanic Trends Project.

[7] Source: http://svapp15586.ksde.org/k12/state_reports.aspx

[8] Source: http://www.ccpe.state.ne.us

[9] Source: http://www.uco.edu/academic-affairs/ir/files/demographic-book/2012-Spring-Demo-Book.pdf

—

Written by: Elena Dain

Written at: John Jay College

Written for: Dr. Ernest Lee

Date written: December 2013

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- State Failure or State Formation? Neopatrimonialism and Its Limitations in Africa

- Constructing a Narrative: Ontological Security in the Scottish Nation (State)

- Humanitarianism and Securitisation: Contradictions in State Responses to Migration

- Australia: Challenges to the Settler State’s Pursuit of Transitional Justice

- The Islamic State’s Guidelines on Sexual Slavery: the Case of the Yazidis

- A Critical Analysis of Libya’s State-Building Challenges Post-Revolution