Securitisation in Practice: Yemen’s Water Scarcity as a Threat to National Security

“Four hundred top-decision makers listed the myriad looming threats to global security, including famine, terrorism, inequality, disease, poverty and climate change. Yet when we tried to address each diverse force, we found them all attached to one universal security risk: fresh water.”

– Margaret Catley-Carlson (2008-2010 Chair of World Economic Forum Global Agenda Council on Water Security, quoted in Waughrey, 2011).

Natural flows of fresh water ignore political boundaries and mock the international reach of environmental development institutions that have increasingly made it their aim to secure this necessity to human survival. As human populations grow, water scarcity and the competition for scarce resources leads “nations to see access to water as a matter of national security” (Gleick, 1993:79). Even though the struggle for resources has been prominent throughout history (see Kaplan, 1994), it was not until the late 1980s that environmental degradation and its consequences were linked to security and we can therefore observe the broadening of the concept of security to include non-state and non-military actors (Lee, 1998:2). The linkage between security and water scarcity can be explained using the concept of securitisation, conceptualized by Barry Buzan, Ole Wæver and Jaap de Wilde (1998), as it shows how the dynamics of the definition of security made it possible for water scarcity to emerge in security debates on both a domestic and an international level. The first part of this essay is going to outline the theory of the concept of securitisation in the framework of the Copenhagen School and its relevance to contemporary International Relations. This will be followed by an illustration of how, through the process of securitisation, water scarcity in Yemen has become securitized and is now seen as a contributing threat to national security. A last paragraph will discuss limitations of the securitisation process, including the risk of broadening the concept of security too far.

Unlike the Aberystwyth School of Critical Security Studies, which provides an explanation of security in terms of emancipation, the dynamics of the Copenhagen School give it the impression of being able to address a broader range of sectors (Waever, 2004). The Copenhagen School securitisation theory offers a unique approach to the dynamics of the definition of security and how it involves a construction of discourse to help develop a specific issue to become an acknowledged security threat that must be prioritized and dealt with “using emergency measures” (Barthwal-Datta, 2012:6). There are three elements of the securitization process that are highlighted by the Copenhagen School: “a securitizing move, a securitizing actor and the audience” (Barthwal-Datta, 2012:6). If these rhetorical criteria are fulfilled, an act is defined as securitized (Buzan et al, 1998:35).

The securitizing act relates to the discursive representation of a chosen specific issue, often regarded as the ‘speech act’, which can be initiated by both state and non-state actors (Buzan et al, 1998:36). As a threat to security must be formulated, and threat-perceptions are articulated through ‘speech acts’ as part of the securitisation process, the definition of security becomes socially constructed; therefore the concept itself is heavily constructivist in its epistemology (Emmers in Collins, 2007:111-113). As such, the Copenhagen School moves away from traditionalist and materialist security studies, such as realism, “widening and deepening the concept of security” and focusing on “non-state and non-military threats” (Emmers in Collins, 2007:119). The ‘speech act’ must be carried out by a securitizing actor, a concept defined as “actors who securitize issues by declaring something, a referent object, existentially threatened” (Buzan et al, 1998:36). Securitizing actors can range from the government to civil society, the military or a political elite, and the “move of securitization depends on and reveals the power and influence of the securitizing actor” as the language of security used must convince a specific audience that the specific subject is an existential threat in order to be a successful act of securitization and allow securitizing actors to proceed with exceptional means (Emmers in Collins, 2007:112). This means that every act of securitization can fail if the discourse used is not persuasive enough to convince the targeted audience and this discursive nature also makes de-securitization and re-securitization possible, emphasizing the flexibility of securitization theory (Barthwal-Datta, 2012:6).

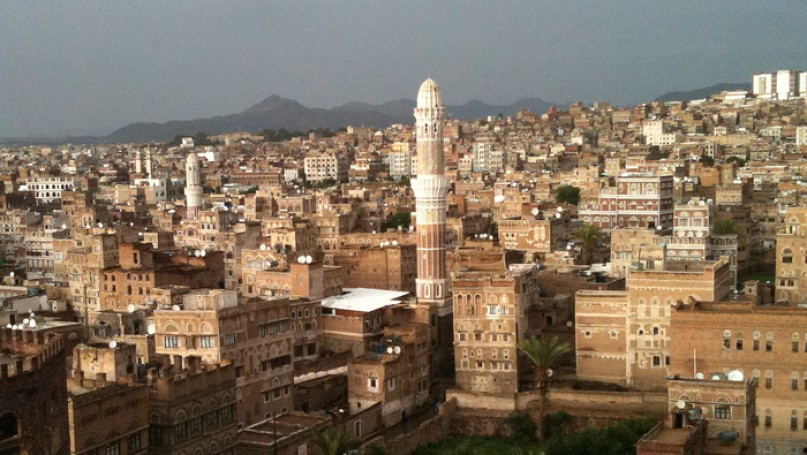

There is a possibility that by 2017, Sana’a, the Capital of Yemen, will become the first capital in the world to run out of water (Osikena, 2010). This threatens the agricultural sector and can pose a threat to internal stability, as there will be increased tensions over access to water (see Homer-Dixon, 1999). A couple decades ago, water scarcity, as a component of climate change, was not viewed as an existential threat to national or human security and much less posed an international threat to economies. However, as the political debate around climate change and the process of globalization intensified, the discourse surrounding water scarcity changed and eventually led to its securitization. One of the first evidenced acts of the securitization of water in Yemen can be observed in 2009, when Abdulrahman Al Eryani, Yemen’s former Minister of Water and Environment, said that water scarcity and the rise of militancy are directly linked:

“They manifest themselves in very different ways: tribal conflicts, sectarian conflicts, political conflicts. Really they are all about sharing and participating in the resources of the country, either oil, or water and land. (…) Some researches from Sanaa University had very alarming figures. They said that between 70-80 percent of all rural conflicts in Yemen are related to water.” (Al Eryani cited in Kasinof, 2009).

This ‘speech act’ performed by Abdulrahman Al Eryani, shows the first stage of the securitization process of water scarcity in Yemen. It makes the referent of this both individuals and a collective, referring to human security in a constructivist manner while linking it to traditional security. By linking the rise of militant powers, an acknowledged securitization act and central part of traditional security studies (Emmers in Collins, 2007:169), to water scarcity, the discourse surrounding this issue gains an increased relation with an already accepted security threat, hence increasing the persuasiveness of the water scarcity securitization act. In 1994, Robert D. Kaplan predicted that a struggle over water can erupt war and will therefore become “the core foreign policy challenge” (Kaplan, 1994:9), as unsuccessful government over a country’s resources can lead to its downfall (Homer-Dixon in Kaplan, 1994:18). From this we can relate the securitization process of water scarcity in Yemen to Mohammed Albasha, the press and public relations officer at the Embassy of Yemen in Washington, who emphasized in 2010 that: “The next big war in the Middle East won’t be over oil, but water” (Bohn, 2010). By securitizing water scarcity, and relating it to traditional threats and national security, it becomes a matter of ‘high’ politics and hence urges governments, and even international organizations, to form responses to this environmental issue that are “equal in magnitude and urgency to their response to more orthodox security threats” (Barnett in Collins, 2007:199). By specifically linking the water discourse to battles involving humans and comparing it to the security struggles that the world has seen over oil-disputes, water becomes a new source for conflict and results in a “new security paradigm” that broadens the security agenda by including another form of non-military threats (Du Plessis in Jacobs, 2012:23). Securitization acts like this have brought water and its scarcity to both a national audience in Yemen and an international audience, with organizations such as the World Economic Forum accepting the securitization act. This is demonstrated by the opening quote, which fulfills the criteria for an act to be securitized.

The Copenhagen School provides a framework for the concept of how any specific issue can be securitized if the targeted audience accepts it. Nonetheless, it is this dynamic of the Copenhagen School that brings limitations to the concept, as increased securitizations of issues can lead to everything becoming securitized (Emmers in Collins, 2007:116), risking insufficient attention being given to certain security threats that might be more imminent than others. Furthermore, there is not always a distinct boundary between the process of politicization and securitization (Emmers in Collins, 2007:117). Especially in regards to developing countries, which often face non-democratic political structures, the separation may remain distinct, whereas democratic political structures may see politicians using the idea of ‘speech acts’ and the discourse surrounding security as a re-election tool, without actually securitizing the specific issue (Emmers in Collins, 2007:117). In regards to the water crisis in Yemen, its “water crisis has the potential to contribute to the country’s instability and potential trajectory toward failure” (Kasinof in Glass, 2010). This highlights that the securitization of water scarcity and resources might have been for political purposes, as the increased struggle for resources poses a threat to the political structure of Yemen, and the securitization of water scarcity might therefore not have specifically served human security. Moreover, even though water scarcity has arguably been securitized in different countries and has reached increased awareness on the international level, there has rarely been a response on a level that can be compared to military-threat responses. It seems as if the securitization of water scarcity is very flexible, and has been de-securitized and re-securitized whenever seen fit with the surrounding circumstances, in order to either increase or decrease the focus on the issue. This shows another limitation of the Copenhagen School, as the nature and the future of securitization processes is not always clear (Barthwal-Datta, 2012:10).

2013 is the United Nations International Year of Water Cooperation (UNWater, 2013), highlighting the international impact that water scarcity and mismanagement of this resource could have on economies globally. The securitization of this issue shows that the securitization concept of the Copenhagen School remains relevant in contemporary international relations. Even though it has some limitations, the water scarcity issue shows that the securitization process works in practice, and has been applied on both domestic and international levels. Nonetheless, there is still no overall responsibility or vision on how to tackle the threat of water security; reminding the audience and international organizations that pure securitization of an issue does not result in its resolution.

Bibliography

Al-Monitor. 2013. Water cooperation for a secure world – Al-Monitor: the Pulse of the Middle East. [online] Available at: http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2013/11/water-cooperation-middle-east-security.html# [Accessed: 24 Nov 2013].

Barthwal-Datta, M. 2012. Understanding security practices in South Asia. New York: Routledge.

Bohn, L. 2013. Yemen’s water: a different national security threat. [online] Available at: http://nationalsecurityzone.org/site/yemens-water-a-different-national-security-threat/ [Accessed: 24 Nov 2013].

Burgess, J. 2010. The Routledge handbook of new security studies. London: Routledge.

Buzan, B., Wæver, O. and Wilde, J. 1998. Security: a new framework for analysis. Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner Pub.

Collins, A. 2007. Contemporary security studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Glass, N. 2010. The Water Crisis in Yemen: Causes, Consequences and Solutions. Global Majority E-Journal, p. 17.

Gleick, P. 1993. Water in crisis. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gleick, P. 1998. Water in crisis: paths to sustainable water use. Ecological applications, 8 (3), pp. 571-579.

Gleick, P. and Cain, N. 2004. The world’s water, 2004-2005. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Global Agenda Council on Water Security 2012-2014 | World Economic Forum. 2013. Global Agenda Council on Water Security 2012-2014. [online] Available at: http://www.weforum.org/content/global-agenda-council-water-security-2012-2014 [Accessed: 24 Nov 2013].

Heffez, A. 2013. How Yemen Chewed Itself Dry | Foreign Affairs. [online] Available at: http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/139596/adam-heffez/how-yemen-chewed-itself-dry [Accessed: 24 Nov 2013].

Homer-Dixon, T. 1999. Environment, scarcity, and violence. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Jacobs, I. 2012. The politics of water in Africa. London: Continuum.

Kaplan, R. 1994. The coming anarchy. Atlantic monthly, 273 (2), pp. 44-76. Available at: http://hope.nps.edu/Academics/Institutes/Cebrowski/Docs/Rasmussen-docs/The%20Coming%20Anarchy.pdf [Accessed: 28 Nov 2013].

Kasinof, L. 2009. At heart of Yemen’s conflicts: water crisis. [online] Available at: http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Middle-East/2009/1105/p06s13-wome.html [Accessed: 24 Nov 2013].

Lee, G. 1998. Regional Environmental Security Complex Approach to Environmental Security in East Asia. International Organization, 52 (4), pp. 855–886.

Osikena, J. 2010. Tackling the world water crisis. Foreign Policy Centre.

Sheehan, M. 2005. International security. Boulder, Colo.: L. Rienner.

Terriff, T. 1999. Security studies today. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

UNWater. 2013. UN-Water Events. [online] Available at: http://www.unwater.org/watercooperation2013.html [Accessed: 24 Nov 2013].

Waever, O. 2010. ‘Aberystwyth, Paris, Copenhagen: New ‘Schools’ in Security Theory and their Origins between Core and Periophery’. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Studies Association, Montral. Delivered on March 17-20. [online] Available at: http://constructivismointergracion.wikispaces.come/file/view/Aberystwyth,+Paris,+Copenhagen+New+’Schools’+in+Secruty.doc [Accessed: 05 Dec 2013].

Waughray, D. ed., 2011. Water security. Washington, D.C: Island Press. [online] Available at: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_WI_WaterSecurity_WaterFoodEnergyClimateNexus_2011.pdf [Accessed: 24 Nov 2013].

—

Written by: Susanne Hartmann

Written at: University of Birmingham

Written for: Dr. Jill Steans

Date written: December 2013

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Security as a Normative Issue: Ethical Responsibility and the Copenhagen School

- To What Extent Is ‘Great Power Competition’ A Threat to Global Security?

- Gender and Security: Redefining the ‘State’ and a ‘Threat’

- Hungary’s Democratic Backsliding as a Threat to EU Normative Power

- Queer Asylum Seekers as a Threat to the State: An Analysis of UK Border Controls

- From Environmental Scarcity to ‘Rage of the Rich’ – Causes of Conflict in Mali