Americans celebrate their founding fathers, such as George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, and the British remember their military heroes, such as Lord Nelson and the Duke of Wellington. Yet Australians recognise few foundation heroes. Elevating individuals to heroic status – placing them ‘on a pedestal’ – is tantamount to anti-Australian behaviour (Horne 1964). With notions of egalitarianism and a ‘fair go’ upheld as key aspects of the national character, hero-worship is discouraged, with the notable exceptions of the cricketer Sir Donald Bradman (Hutchins 2002) and the 19th century outlaw Ned Kelly (Tranter and Donoghue 2010). In Australia, individuals who achieve heroic status tend to be seen as ‘tall-poppies’ and are often quickly cut down (Macintyre 2009: 255). Foundation heroes are largely absent from the Australian ‘mythscape’ (Bell 2003), perhaps because Australians have not endured a civil war, faced revolution or military invasion. Indigenous Australians may disagree with the latter claim, yet they too have been largely ignored in Australian identity narratives following the establishment of British penal colonies in 1788.

Instead, Australians celebrate the deeds of their World War I soldiers, known collectively as the ‘Anzacs’, originally an acronym for the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps. However, most Australians could identify very few individual Anzacs. The Anzacs remain largely nameless, apart, perhaps, from the Australian General Sir John Monash, and the field ambulance stretcher bearer Private John ‘Jack’ Simpson Kirkpatrick (aka John Simpson) and his donkey. The latter carried wounded soldiers from the battlefield regardless of enemy fire for three and a half short weeks before his death on 19th May 1915.

The Anzac myth refers to the exploits of brave young soldiers keen to prove themselves as representatives of a fledgling nation, albeit one with an ignominious convict past (Bennett 1988; Sayle 1988), who performed heroically for their ‘new’ nation which was formed only a generation earlier in 1901. In fact, many Anzacs fought as British Empire troops under the British flag at a time when many Australians referred to the United Kingdom as the ‘old country’ and still regarded themselves as British. Although many Anzacs undoubtedly fought bravely in extremely difficult conditions, their heroism has been embellished by journalists and war correspondents. Charles Bean, in particular, actively sought out stories of heroism on the battlefield and was instrumental in claiming that the Australian nation was ‘born’ at Gallipoli (Crotty 2009: 101). With the passing of almost 100 years since these youthful, citizen soldiers stormed what has come to be known in Australia as Anzac Cove, the Anzacs have come to be revered as national heroes and comprise a foundation element of the national narrative (Day 1998; Donoghue and Tranter 2013).

Yet although the Anzac myth is well known in Australia, how important are the Anzacs for understanding national identity? We aim to gauge Australians’ attitudes toward Anzacs, with our study situated in an empirical field of national identity research based upon quantitative methodology (e.g. Phillips 1998; Pakulski and Tranter 2000; Rusciano 2003). Drawing upon results from a representative sample of Australian adults, we provide survey evidence to examine the importance of the Anzac myth for contemporary notions of Australian identity. National identity necessarily requires a referent ‘nation’, conceptualised here following Smith (1991: 14) as ‘a named human population sharing an historic territory, common myths and historical memories, a mass, public culture, a common economy and common legal rights and duties for all members’. While national identity is clearly multidimensional (Smith: 1991: 14), it is the shared myths, memories, and culture that are particularly relevant to our research. The Anzac myth evolved from the stories by war correspondents (Lake et al. 2010), who connected their sacrifice with the birth of the nation (Day 1998).

We ask, how important are the Anzacs for contemporary Australians vis a vis other historical figures of national significance? To what extent can differences in the social and political background of Australians inform us about the longevity of the Anzacs as a national myth? For example, with the resurgence in support for Anzac Day marches in recent years, are younger people more supportive of the Anzac myth than their older counterparts? Are men more likely to be attracted to the romanticism of war and military heroes than women, and to what extent do educated cosmopolitans reject the Anzac myth? Before exploring these questions empirically, we provide a description of our survey data and research approach.

Data and Method

The Australian Survey of Social Attitudes (AuSSA) data are analysed here (Evans 2012). The AuSSA is based upon a representative sample of Australian adults aged 18 or over, sampled systematically from the Australian Electoral Roll in June 2011. Data collection for this mail survey commenced in late 2011 and ended on the 1st of May 2012. The sample size for the 2011 AuSSA is 1,946, with a response rate of 31 per cent. The AuSSA includes a weight variable designed by the survey investigators to adjust the sample for national representativeness on the basis of age, sex, and educational attainment, according to the 2011 Australian Census (Evans 2012). The weight variable is applied in the analyses below using SAS version 9.2. We did not replace missing cases in the analyses presented here.

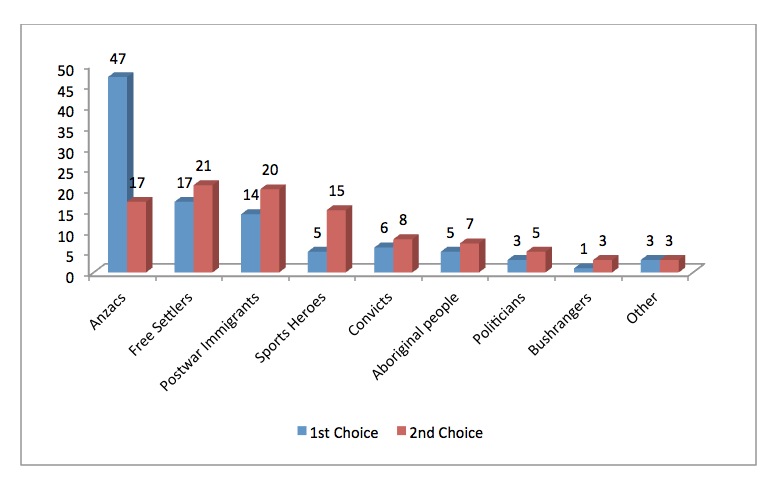

We begin by presenting responses to a series of questions we designed for the 2011 AuSSA in order to examine the influence of a variety of historical figures on Australian national identity (Figure 1). Categories are listed in historical order. Aboriginal people are followed by convicts and free settlers, who were the first ‘white’ Australians. Australian bushrangers (outlaws) were folk heroes for many and, as we suggest above, Anzacs are a rare example of foundation heroes in Australia. Following the Second World War, large numbers of European migrants settled in Australia and played important roles in the development of the country. Sporting heroes were included, given popular perceptions of Australia as a sporting nation that ‘punches above its weight’, followed by political leaders, and, finally, ‘other, please specify’ to capture important responses that we may have omitted.

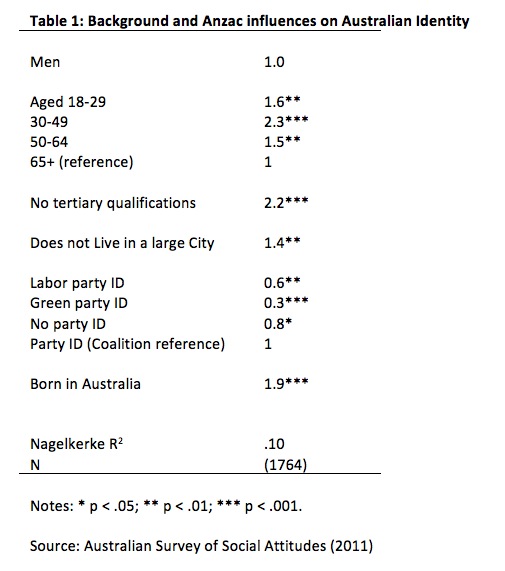

Unlike previous survey-based research of this nature (e.g. Tranter and Donoghue 2007), we rank responses in order of their importance, rather than rate the importance of individual items for assessing the most influential Australians in relation to national identity. We then present the results of binary logistic regression analysis (Agresti and Finlay 1999), where responses to the Anzacs item is measured as a dichotomous dependent variable (1 = Anzacs; 0 = other responses) to illustrate social and political background differences on responses to the importance of Anzacs for Australian identity (Table 1). The AuSSA contains a range of socio-demographic questions that allow us to examine background variations according to sex, age, educational achievement, location, religious denomination, political party identification, and country of birth.

The Importance of Anzacs

Data from the 2011 AuSSA suggest that Anzacs are by far the most influential historical figures in relation to Australian identity (Figure 1). Anzacs were chosen by 47 per cent of respondents as their first choice, with a further 17 per cent selecting them second. The next most important first choices were free settlers with 17 per cent and postwar immigrants on 14 per cent, while these categories were chosen by 21 per cent and 20 per cent as their second choice. Other groups received much lower responses, with only 5 per cent of the sample choosing sporting heroes as most important first choice as having the most influence on Australian identity, although 15 per cent chose sports heroes as their second choice. All other historical groups received far lower responses. The low proportion of responses to the ‘other, please specify’ category indicates that our groups form a relatively complete list. These findings provide strong empirical confirmation of the importance of the Anzac myth for Australian identity, relative to other historical figures. We now consider how the social and political background of Australians influences responses on the Anzacs dependent variable. That is to say, to what extent do influences upon Australian identity vary according to socio-demographic factors and political affiliations?

Figure 1 – Source: Australian Survey of Social Attitudes (2011): ‘Many people throughout Australia’s history have influenced the way Australians see themselves in terms of their identity as Australians. If you had to choose among the following, which would be your first choice as the most influential? Which would be your second choice?’

Regression Analyses

In Table 1, we use binary logistic regression to model the impact of social background on the dependent variable Anzacs. Odds ratios (OR) generated from the logistic regression estimates are presented, with OR of magnitude less than 1 indicating a negative association between an independent and the dependent variable. For example, the OR of 0.6 for Australian Labor Party (ALP) identifiers suggests that the odds of ALP identifiers choosing Anzacs over other categories are 1.7 times (i.e. 1 ÷ 0.6 = 1.666) less than the Coalition identifier (i.e. Liberal and National party) reference category. Alternatively, the OR of 1.9 for those born in Australia indicates that the odds for this category are 1.9 times larger than those born elsewhere to rank Anzacs as the most influential category.

The Nagelkerke R2 is rather modest, although given these are social survey data, large pseudo R2 were not expected. While there is no effect for sex here, those under 65 years of age tend to rank Anzacs as more influential than their older counterparts, with the largest age-related OR found among the 30-49 year group. The non-tertiary educated are more likely than their highly educated counterparts to prioritise Anzacs, as are those who live outside large cities, compared to city dwellers.

Country of birth is an important indicator. The Australia-born are more likely than immigrants to prioritise Anzacs, while there is also a political divide, particularly between the more progressive Greens and Labor identifiers and those affiliated with the conservative coalition parties (i.e. Liberals and National party). Greens, Labor, and even those who are not aligned with any political party are all more likely than Coalition identifiers to rank Anzacs highly as having an influential impact upon Australian identity. The results suggest that tertiary educated, cosmopolitan citizens who are aligned with progressive political parties are least likely to prioritise the importance of Anzacs for Australian identity.

Discussion

Although criticised by some academics as anachronistic (e.g. Lake et al. 2010; Day 1998), this research demonstrates that, in the popular imagination, Anzacs are an integral aspect of what it means to be Australian. Anzacs contribute strongly to the myth of Australian identity formation, with Anzac Day celebrations and dawn vigils, in Australia and abroad, commemorating and perpetuating the Anzac legend (Donoghue and Tranter 2013). While the reputation of Anzac Day was affected in the 1970s by the Vietnam War and criticised in literary circles (e.g. Seymour’s 1963 play The One Day of the Year), the popularity of Anzacs ceremonies has grown since the 1990s. Support for Australia’s military heroes appears to be stronger among younger people than ever before. Certainly our findings show that it is younger and middle-aged Australians who are most likely to associate Anzacs closely with Australian identity, suggesting the phenomenon is unlikely to die out in the near future. However, Anzacs are far less likely to be prioritised as important among the tertiary educated, city dwellers and those who identify with left-leaning political parties.

For Smith (1991: 161), a nation must boast ‘a glorious past, a golden age of saints and heroes, to give meaning to its promise of restoration and dignity’. The Anzacs are the closest Australia comes to approximating the ‘saints and heroes’ of a golden age. In terms of their national identity, Australians, or at least many of them, fall back on the myth of Anzac to claim what is ‘authentically theirs’ (Smith 1991: 67), and as a relatively young settler society, draw upon these collective heroes in an attempt to establish a national identity of their own. When former Prime Minister John Howard stated, ‘I am an Anzac Bradman Australian’, he was, according to Kelly (2009: 328) ‘defining himself by the symbols of the past not the future’. Yet by aligning himself with the powerful Anzac myth and the popular sporting hero Sir Donald Bradman, John Howard was paying homage to the conservative cultural symbols that are still valued by many younger Australians in the 21st century.

References

Agresti, A. and Finlay, B. (1999) Statistical Methods for the Social Sciences, (3rd edition) New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Bell, D. (2003) ‘Mythscapes: Memory, Mythology, and National Identity’ British Journal of Sociology 54(1): 63-81.

Bennett, T. (1988) ‘Convict Chic’ Australian Left Review 106: 40-1.

Crotty, M. and Roberts, D. (eds.) (2009) Turning Points in Australian History, Sydney: University of New South Wales Press.

Day, D. (1998) (ed.) Australian Identities, Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing.

Donoghue, J. and Tranter, B. (2013) ‘The Anzacs: Military influences on Australian Identity’ Journal of Sociology DOI: 10.1177/1440783312473669.

Evans, A. (2012) The Australian Survey of Social Attitudes, 2011, Australian Demographic and Social Research Institute, Canberra: Australian National University.

Horne, D. (1964) The Lucky Country, London: Penguin.

Hutchins, B. 2002 Don Bradman: Challenging the Myth, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Kelly, P. (2009) The March of Patriots: The Struggle for Modern Australia, Melbourne University Press.

Lake, M., Reynolds, H., McKenna, M. and Damousi, J. (2010) What’s Wrong With Anzac?: The Militarisation of Australian History, Sydney: University of New South Wales Press.

Macintyre, S. (2009) A Concise History of Australia (3rd Edition), Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

Pakulski J. and B. Tranter (2000) ‘Civic, National and Denizen Identity in Australia’ Journal of Sociology 36 (2):205-222.

Phillips, T. (1998) ‘Popular views about Australian identity: research and analysis’ Journal of Sociology 34(3): 281-302.

Rusciano, F. (2003) ‘The Construction of National Identity- A 23-Nation Study’ Political Research Quarterly 56(3): 361-366.

Sayle, M. (1988) ‘Where convicts are chic and the past looks good’ Far Eastern Economic Review 139(4):44-50.

Seymour, A. (1963) ‘The One Day of the Year’ in Three Australian Plays, Ringwood: Penguin.

Smith, A. (1991) National Identity, Reno, University of Nevada Press.

Tranter, B. and Donoghue, J. (2007) ‘Colonial and Postcolonial Aspects of Australian Identity’ British Journal of Sociology 58(2): 165-183.

Tranter, B. and J. Donoghue (2010) ‘Ned Kelly: Armoured Icon’ Journal of Sociology 46(2): 187-205.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Paradox(es) of Diasporic Identity, Race and Belonging

- War and Identity: The Path to Trump and Beyond

- The European Identity: An Attempt at a Novel Approach

- Undoing Sovereignty/Identity, Queering the ‘International’: The Politics of Law

- Opinion – Getting Diversity ‘Right’ In Australia’s Nascent Space Industry Matters

- Revitalizing the Commonwealth Framework: A Political Tool for Australia and the UK?