Japan is not a nuclear weapons state. Scholars have debated why Japan – an advanced industrialised country, in the world’s most militarised region, and with a nuclear North Korea on its doorstep – has not sought atomic weapons to increase its own security (Hughes 2007; Kamiya 2002-03; Samuels 2007, p. 176). Japan is certainly capable; it has a highly sophisticated nuclear technology sector, which has the potential to be Asia’s most sophisticated nuclear weapons state (Windrem 2014).[1]

In the last decade, Japan has received a renewed focus with some scholars noticing a newfound bout of nationalist attitudes and calls for a review of Japan’s non-nuclear policy (Mathews 2003). Despite observations of rising nationalism, however modest, most scholars believe that domestic constraints and the strength of the US-Japan alliance will restrict Japan from pursuing a nuclear weapons program in the near-future (Hughes 2007; Hymans 2011; Solingen 2010). In short, the prevailing opinion is that Japan’s political norms and American power will only extend Japan’s current strategy (Curtis 2014).

This essay supports the argument that Japan requires more than a ‘mood swing’[2] before becoming a fully-fledged nuclear weapons state. Evidence presented in this essay adds to the discourse that a combination of domestic and regional factors is likely to hinder a change from the status quo (Hughes 2007; Hymans 2011; Kamiya 2002-03). Thus, a continuation of Japan’s non-nuclear policy will prevail in the near future.[3]

Predicting an Atomic Japan

Predicting proliferation is fraught with problems. Montgomery and Sagan (2009, pp. 309-311) illustrate that quantitative studies fail to accurately predict Japanese proliferation due to inadequate datasets and lax coding. As such, Japanese proliferation is frequently tested using qualitative analysis – often with an emphasis on domestic factors (Solingen 2007; Solingen 2010). Thus, this essay also presents a number of domestic factors that may influence Japan’s non-nuclear policy. For reasons of brevity, not all factors can be discussed.

Japan has been a global supporter of the international abolition of nuclear weapons. Three key factors have contributed to this position. Firstly, a strong anti-nuclear weapons culture developed in the wake of America’s use of two nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki (Tomohiko 2009, p. 4). Secondly, Article 9 of Japan’s Constitution has helped to create a ‘pacifist’ strategic culture, whereby sentiments against a strong resurgent military are blocked (as are discussions on nuclear weapons). Thirdly, Japan’s alliance with the US – and subsequent nuclear ‘umbrella’ – has allowed Japan to develop a nuclear weapons free defence force (Packard 2010). For instance, most polls reveal that Japanese public sentiment is firmly opposed to nuclear weapons, and that only a significant cultural and societal change would alter this position (Chanlett-Avery & Nikitin 2009, p. 7). Japan has been an advocate for the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons Treaty (NPT), the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), initiated UN conferences on disarmament, and contributed to the Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI) (Tomohiko 2009, p. 4). Also, as Packard says, despite some minor concerns, the US-Japan Security Treaty remains robust and ‘has lasted longer than any other alliance between two great powers since the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia’ (Packard 2010, p. 92).

What Has Changed?

Some scholars, however, have noted a renewal in Japanese nationalism that has contributed to new discussions about Japan’s current strategic and defence policies (Mathews 2003). Most notably, Japanese politicians have been testing the 60-years strong taboo against nuclear weapons. A Tokyo Shimbunpoll found 83 of 724 members of the Diet (parliament) publicly supported Japan becoming a nuclear weapons power in light of the North Korean threat (Fukuyama 2005, p. 81). In 2002, the Chief Cabinet Secretary, Yasuo Fukuda, said that the debate about re-evaluating Japan’s Constitution (specifically Article 9) might also see amendments to the non-nuclear policy (French 2002). Despite this and other off the cuff remarks, official government policy continues to stress Japan’s non-nuclear stance. On the 40th anniversary of the NPT in 2010, Mr Katsuya Okada, Minister for Foreign Affairs, said:

‘Japan highly values this treaty, with its 190 states parties, for having contributed to the realization and maintenance of international peace and security … Japan intends to play an active role at the Global Nuclear Security Summit in April and the 2010 NPT Review Conference in May, thus contributing toward achieving ‘a world without nuclear weapons’ (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2010).

Even so, regional concerns over China and North Korea are spawning a thorough discussion about Japan’s self-defence forces (Fukuyama 2005, p. 78). Some believe that Japan, as a significant economic and regional power, should possess a traditional standing army (Fukuyama 2005, p. 78). In 2013, Japan unveiled a new 250m long, 24,000 ton naval vessel that was promoted as a helicopter destroyer, but which analysts remarked could be easily converted into an aircraft carrier (Keck 2013). Also, Japan maintains the world’s eighth largest military budget with about US$48.6b spent in 2013 alone (Perlo-Freeman & Solmirano 2013, p. 2). However, some of the expenditure is attributed to basic upgrades or replacements and forms part of a pragmatic approach to regional security concerns. Plus, Japan’s defence budget has shrunk in each of the last 11 years (Curtis 2014).

In response to North Korea missile tests, Japan has worked more closely with America to upgrade the Theatre Missile Defense System. Some say this could encourage Japanese policymakers to reconsider Japan’s broader national security policies, which would have direct implications on the country’s non-nuclear weapons policy (Monten & Provost 2005). However, such a change has not yet occurred and it is not obvious that establishing a nuclear weapons program could be easily implemented. A number of hurdles need to be overcome before Japan could develop its own program.

Capability

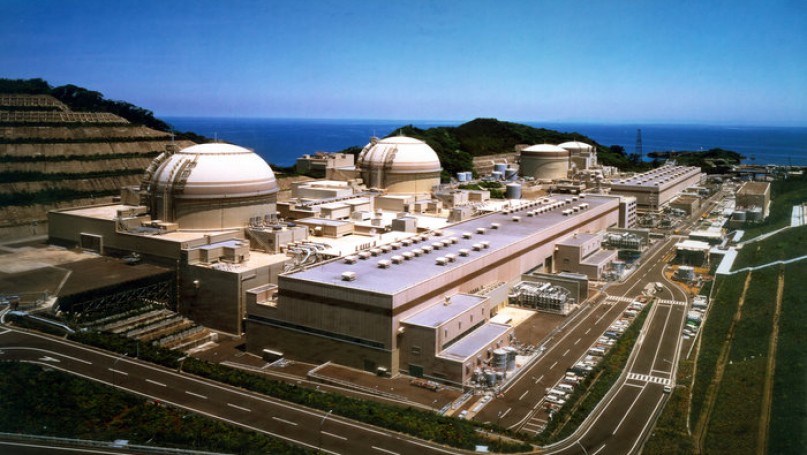

Capability does not necessarily mean creation. Japan is technologically proficient in nuclear technology with an advanced nuclear energy sector as well as plutonium processing facilities to prolong the nuclear fuel cycle (Hughes 2007, p. 82; Kamiya 2002-03). It is estimated that Japan owns 44 tons of separated unirradiated plutonium (Rauf 2014). Granted, these stockpiles remain in civilian or private use, are subject to the full scope of International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards, and only five per cent of the total stockpile is estimated to actually be in Japan (Hymans 2011, p. 186). This level of sophistication far exceeds that of Asia’s actual nuclear weapons states: China, India, Pakistan, and North Korea. As such, Japan has the potential to be Asia’s most sophisticated nuclear weapons state. Given Japan’s technological prowess and plutonium stockpiles, it is estimated that Japan could potentially assemble a nuclear weapon within 12 months and as many as 5,000 warheads (Windrem 2014). Despite this capability, erroneous predictions about Japan becoming a nuclear weapons state are not new. In 1957, America’s National Intelligence Estimates identified Japan as a leading candidate to pursue a nuclear weapons program ‘within the next decade’ (Potter & Mukhatzhanova 2010, p. 1). Hence, more than capability is required to explain future proliferation.

Feasibility

Even if a nuclear weapons program is feasible, the implications are broad. A domestic legal impediment restricts the civilian transfer of nuclear materials to military use. This requirement was legislated in the 1955 Basic Law on Atomic Energy (Hughes 2007, p. 88). However, the Japanese Diet could remove this legislation with support from opposition parliamentarians. In 2002, the then deputy chief cabinet secretary, Shinzo Abe (now Prime Minister), publicly said that Japan could legally develop nuclear weapons as long as stockpiles remained ‘small’ – meaning for defensive purposes (French 2002). But as a member of the NPT, Japan would be breaking international law, unless it chose to withdraw from the treaty. But even then, withdrawing from the treaty might isolate Japan diplomatically and alarm regional neighbours. As such, Japan would not only need to acquire domestic legal support, but must consider the international implications of pursuing a nuclear weapons program. For instance, Francis Fukuyama says that Japanese rearmament should not threaten its Asian neigbours (Fukuyama 2005, p. 78). But given historical grievances from World War II, it could create an Asian arms race (Chanlett-Avery & Nikitin 2009, p. 11).

Practicality

Determining how easily Japan could change from its non-nuclear policy to a pro nuclear weapons policy depends on one’s interpretation of how policy is formed. Determining the extent of change can be drawn from two perspectives. First, some argue that policy decisions are made on the run, suddenly, and unpredictably. Others, however, take the opposite view, regarding such events as the result of ‘big, slow-moving and invisible’ processes (Pierson 2003, p. 1). The latter believe in a continual strategic culture embedded in a state’s foreign policy, irrespective of the ruling party’s aims (Lynch & Singh 2008). This latter strategic cultural explanation is more persuasive as it helps to explain why Japan has not altered its non-nuclear policy in a swifter manner.

In addition, Japan’s political structures should provide an easier route to effecting policy change rather than comparatively similar liberal states. Scholars have noted that the greater the level of legislative unity, the easier foreign polices can be executed (Prins & Sprecher 1999, p. 285). For instance, Leblang and Chan (2003, p. 388) said ‘one should expect Japan (a state which has experienced continual rule by a single dominant party) to be more war prone than the U.S. (which features a more competitive two-party system)’. Despite this, swift political change in response to advancing a more robust nuclear weapons policy has not materialised.

Of course, politicians are not the only actors that influence policy outcomes. The general public, media, industry, unions, universities, and more contribute to policy debates. Japan seems to be unique, having a high level of state and non-state actors within the nuclear debate that make it hard to gather the political will to make a bomb (Hymans 2011). Hymans’ analysis leads him to believe that Japan’s current non-nuclear weapons policy ‘could well continue indefinitely’ (Hymans 2011, p. 157). While it may be feasibly challenging for Japan’s political elites to change the current status quo, Japanese elites also need to consider whether obtaining nuclear weapons is even required.

Necessity

The American nuclear security umbrella has influenced Japan’s decision to continue its anti-nuclear stance(Hughes 2007, p. 75). The security guarantee is underpinned by the United States-Japan Security Treaty, which marked its 50th anniversary on 19 January 2010.[4] The benefits of the pact were mutually beneficial: Japan provided America with the world’s largest ‘unsinkable aircraft carrier’ for which America could execute its strategic objectives in East Asia, while America guaranteed Japan’s security, allowing Japan to rebuild its economy, access American markets, and keep defence spending minimal (Packard 2010, p. 96). There are several conceptual scenarios where Japan might consider establishing their own nuclear weapons program. While tensions always exist in any bilateral relationship, the alliance is being bolstered, in part, due to the US pivot to Asia. If the US were to significantly withdraw from the region, Japan would be inclined to bolster its defence capabilities and review its overall strategic position. Also, if the US were to heavily reduce its stockpile, it might put into question America’s ability to effectively protect Japan, tempting Japan to establish its own weapons program (Deutch 2005, p. 51). In addition, Hugh White (2011) has suggested that Japan’s reliance on US security could become a liability if the US-China relationship blossomed, causing Japan’s interests to be sidelined and encouraging Tokyo to increase its strategic position.

Conclusion

Japan’s non-nuclear policy appears to be a pragmatic realisation of numerous domestic factors, perceptions of regional security, and faith in the US alliance. Domestic legal impediments, public pressure, and historical norms have influenced policy outcomes. Regional concerns over North Korea’s nuclear weapons program and China’s rising military also feature prominently in Japan’s strategic assessment. These developments have helped to create a new wave of reformist politicians keen to advance nationalist policies aimed at reforming Japan’s foreign and defence policies. However, domestic and international factors have not caused enough consternation to activate an indigenous nuclear weapons program – however easy that may be. Ultimately, Japan is likely to pursue a continuation of its non-nuclear policy and rely on US nuclear deterrence for the near-future.

References

Curtis, G 2014, ‘Japan’s Cautious Hawks’, Foreign Affairs, vol 92, no. 2, pp. 77-86.

Chanlett-Avery, E & Nikitin, MB 2009, ‘Japan’s Nuclear Future: Policy Debate, Prospects and U.S. Interests’, Congressional Research Service, RL34487.

Deutch, J 2005, ‘A Nuclear Posture for Today’, Foreign Affairs, vol 84, no. 1, pp. 49-60.

Fukuyama, F 2005, ‘Re-Envisioning Asia’, Foreign Affairs, vol 84, no. 1, pp. 75-87.

French, HW 2002, Taboo Against Nuclear Arms Is Being Challenged in Japan, viewed 20 April 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2002/06/09/world/taboo-against-nuclear-arms-is-being-challenged-in-japan.html.

Hughes, L 2007, ‘Why Japan Will Not Go Nuclear (Yet): International and Domestic Constraints on the Nuclearization of Japan’, International Security, vol 31, no. 4, pp. 67–96.

Hymans, JEC 2011, ‘Veto Players, Nuclear Energy, and Nonproliferation: Domestic Institutional Barriers to a Japanese Bomb’, International Security, vol 36, no. 2, pp. 154-189.

Howell, WG & Pevehouse, JC 2007b, ‘When Congress Stops Wars: Partisan Politics and Presidential Power’, Foreign Affairs, vol 86, no. 5, pp. 95-107.

Kamiya, M 2002-03, ‘Nuclear Japan: Oxymoron or Coming Soon?’, Washington Quarterly, vol 26, no. 1, pp. 63–75.

Keck, Z 2013, Japan’s Unveils “Aircraft Carrier in Disguise”, viewed 22 April 2014, http://thediplomat.com/2013/08/japans-unveils-aircraft-carrier-in-disguise/.

Lynch, TJ & Singh, RS 2008, After Bush: The Case for Continuity in American Foreign Policy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Leblang, D & Chan, S 2003, ‘Explaining wars fought by established democracies: Do institutional constraints matter?’, Political Research Quarterly, vol 56, no. 4, pp. 385-400.

Mathews, EA 2003, ‘Japan’s Rising Nationalism’, Foreign Affairs, vol 82, no. 6, pp. 74-90.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2010, Statement by Mr. Katsuya Okada, Minister for Foreign Affairs, on the 40th Anniversary of the Entry into Force of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), viewed 22 April 2014, http://www.mofa.go.jp/announce/announce/2010/3/0305_02.html.

Monten, J & Provost, M 2005, ‘Theater Missile Defense and Japanese Nuclear Weapons’, Asian Security, vol 1, no. 3, pp. 285-303.

Montgomery, AH & Sagan, SD 2009, ‘The Perils of Predicting Proliferation’, Journal of Conflict Resolution, vol 53, no. 2, pp. 302-328.

Packard, GR 2010, ‘The United States–Japan Security Treaty at 50: Still a Grand Bargain?’, Foreign Affairs, vol 89, no. 2, pp. 92-103.

Perlo-Freeman, S & Solmirano, C 2013, ‘Trends in World Military Expenditure’, Fact Sheet, SIPRI, Stockholm.

Pierson, P 2003, ‘‘Big, slow-moving, and invisible: macro-social processes in the study of comparative politics’’, in J Mahoney, D Rueschmeyer (eds.), Comparative historical analysis, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Potter, WC & Mukhatzhanova, G 2010, Forecasting Nuclear Proliferation in the 21st Century: The Role of Theory, 1st edn, Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Prins, BC & Sprecher, C 1999, ‘Institutional Constraints, Political Opposition, and Interstate Dispute Escalation: Evidence from Parliamentary Systems, 1946-89’, Journal of Peace Research, vol 36, no. 3, pp. 271-287.

Rauf, T 2014, Looking beyond the 2014 Nuclear Security Summit, viewed 23 April 2014, http://www.sipri.org/media/expert-comments/rauf_mar2014.

Samuels, RJ 2007, Securing Japan: Tokyo’s Grand Strategy and the Future of East Asia, Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

Solingen, E 2007, Nuclear Logics: Contrasting Paths in East Asia and the Middle East, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Solingen, E 2010, ‘The Perils of Prediction: Japan’s Once and Future Nuclear Status’, in Forecasting Nuclear Proliferation in the 21st Century: A Comparative Perspective, Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Tomohiko, S 2009, ‘Japan’s nuclear policy: Between non-nuclear identity and US extended deterrence’, Austral Policy Forum, Nautilus Institute, 09-12A.

Windrem, R 2014, Japan Has Nuclear ‘Bomb in the Basement,’ and China Isn’t Happy, viewed 23 April 2014, http://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/fukushima-anniversary/japan-has-nuclear-bomb-basement-china-isnt-happy-n48976.

White, H 2011, ‘The Foundering Miracle’, The Monthly, pp. 34-35.

[1]Although Japan would still be restricted under international law by its membership to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). This point is later further discussed.

[2] By ‘mood swing’, Mathews (2003, p. 161) suggests that altering Japan’s nuclear status quo would require more than a policy change by Japan’s top politicians.

[3] In this case, near-future generously refers to within a 10-year period. Any time after which is hard to gauge as domestic and regional circumstances are likely to change significantly, requiring a re-evaluation.

[4] See George Packard’s (2010) article for an insightful summary on the key issues affecting the bilateral relationship.

—

Written by: Heath Pickering

Written at: University of Melbourne

Written for: Richard Tanter

Date written: May 2014

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Gendered Dimensions of Anti-Nuclear Weapons Policy

- Halakhah and Omnicide: Legality of Tactical Nuclear Weapons under Jewish Law

- The Dangerous Double Game: The Coexistence of Nuclear Weapons and Human Rights

- Deterrence and Ambiguity: Motivations behind Israel’s Nuclear Strategy

- EU Foreign Policy in East Asia: EU-Japan Relations and the Rise of China

- Balancing Rivalry and Cooperation: Japan’s Response to the BRI in Southeast Asia