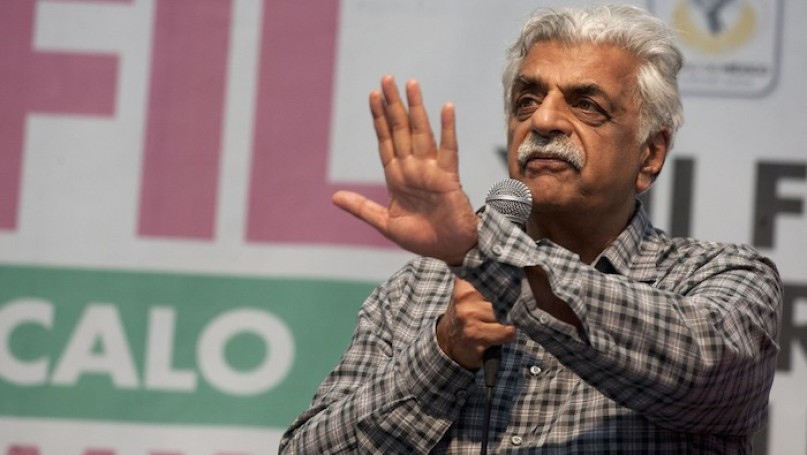

Tariq Ali is a longstanding editor of the New Left Review. He has written seven novels and a number of screenplays, in addition to many works on history and world politics. His latest books are On History: Tariq Ali and Oliver Stone in Coversation and The Obama Syndrome.

In this interview, Tariq Ali discusses the recent Israel-Palestine conflict, the BDS movment, the rise of ISIS, and Obama’s commitment to long-term US involvement in Iraq.

How has the way you understand the world changed over time, and what (or who) prompted the most significant shifts in your thinking?

I was born 26 years after the Russian Revolution and 6 years before the Chinese Revolution. I was 11 years old when the Vietnamese defeated France at the epic battle of Dienbienphu. These events played a big part in my political biography. One had to read Marx, Lenin, Trotsky, and Mao. Initially uncritically, later with a more critical eye. This I did in Pakistan. The Cuban Revolution had very little impact on the Left in Asia—except during the missile crisis—and so it was not till I arrived to study at Oxford in October 1963 that I really understood what had happened in Cuba and read a great deal of Fidel and Che. When the Soviet Union collapsed, one understood that it was the end of an epoch. One couldn’t just say, ‘Ah, the slate has been wiped clean and we can start afresh’. What happened marked the triumph of capitalism and the ideologies associated with it. Broadly speaking, a global counter-revolution. So what was to be done?

For some on the left, mainly uncritical admirers of the various Communist regimes, the choice was simple. Always worshippers of accomplished facts, they shifted their loyalties to the new order, becoming as dogmatic in its defence as they had once been in relation to Russia, China, Yugoslavia, North Korea, Albania, etc., etc. For them, the new emancipatory project became ‘globalisation’, the United States and NATO or, in the case of some, Israel. This process is not exactly novel. It happened after the Restoration in 17th century Britain. Christopher Hill has written an illuminating study on precisely this: ‘The Experience of Defeat’. The process was repeated again after the final defeat of the revolution in France. Stendhal wrote about this phenomenon very well. And so it goes. One must recognise the defeat, but one must not capitulate to ‘presentism’. Because what is now is not permanently static. Things change. By the end of this century, the trajectory might be clearer. To give up, to say farewell to what was important about many of the ideas that motivated people in the last century, is foolish.

There has been much discussion in the media of the so-called moral high ground in the current crisis involving Israel-Palestine. Taking into consideration how events have played out, do you see either side having a serious claim to this?

‘Moral high ground’ is not a phrase I ever use. One person’s moral high ground can be another person’s dungeon. In the overall conflict the Palestinians are in the right. Much wrong has been done to them by Israel and its principal backer, the United States. The Israelis treat them as untermensch, have tried to destroy their past, their historical memory, and are now attempting to destroy them as a political entity.

What do you feel are the Israeli government’s current political aims in Gaza?

The destruction of Hamas, the intimidation of those who vote for it, and the institution of a puppet regime that is a twin of the Palestinian equivalent of the Judenrat that exists on the West Bank. This aim is supported by Washington, Riyadh, and Cairo, as well.

You’ve recently pointed out, in an interview with the BBC and in a talk for the Stop the War Coalition, that you feel there has been a change in the perception of the conflict, particularly the Israeli use of force, from those who were previously described as neutral and from those who were previously in the strongly pro-Israel camp. Do you feel that this shift in opinion offers hope to the Palestinians?

Opinion polls in Europe indicate that a vast majority of European citizens are opposed to Israel’s most recent assault on Gaza, but this was also the case on Iraq. On its own, public opinion has no real force. So the shift will certainly give succour to the Palestinians, make them feel they’re not alone, but that is not sufficient to alter the overall situation.

The BDS movement has been criticized recently by those who are also considered stern critics of the Israeli government, such as Noam Chomsky and Norman Finkelstein. Do you think the BDS movement is still an effective approach?

I don’t agree with the two N’s on this question. I think they’re wrong. What else can one do? It’s the only alternative to non-violence. Mustafa Barghouti, the secretary-general of the Palestinian National Initiative movement, has estimated that Israel has incurred losses of around eight billion dollars due to the boycott campaign against illegal settlements, equivalent to 20 per cent of their GDP. If the figure is accurate, the movement has been a success.

What are your thoughts on Obama’s commitment of the US to long-term involvement in Iraq, which he claims is a response to the rise of Islamic militants?

Nonsense. The real reason is to make sure that the US-Israeli protectorate [Kurdish region] remains safe. The aftermath of the occupation was designed to divide Iraq across religious lines. What we are witnessing (as I pointed out a decade ago) is the balkanisation of Iraq.

Do you agree with Hillary Clinton’s recent statement that the rise of ISIS can be attributed to the failure of the US to help rebels in Syria?

Another absurdity. The US did help and arm the Syrian rebels via Turkey. They did not bomb Assad out of existence, as they were unsure of the consequences. After all, Clinton, who supported the war on Iraq, should see what happens if you destroy a regime unilaterally. The rise of ISIS in Iraq is because they destroyed all the structures of the old regime. Had they done the same in Syria, we would have had an even worse situation than now, with at least three different wars taking place. Qatar/Turkey/US backing the so-called moderate Islamists, and the Saudis angry that the Muslim Brotherhood is being revived in Syria.

It is arguable that some of the loudest voices currently calling for military intervention in Iraq, who were previously calling for military intervention in Syria, are coming from what could be described as the Euston Manifesto Left. What effect do you feel the Euston Manifesto has had on the political Left since it was created, and do you think it actually represents what it claims to represent, i.e. modern leftist internationalism?

Are these people on the Left? I think I described them in my response to your first question. They’re liberal imperialists, a position that has a long pedigree in Britain. The Fabians and mainstream Labour upheld the British Empire and defended its values long after the independence of India in 1947. Labour Governments played an appalling role in Malaya and Aden in the late Forties, Fifties, and Sixties. They had no need of a ‘humanitarian’ ideology, since they were still infected by civilizational zeal.

Many of E-International Relations’ readers are students. What key advice would you give those wanting to start a career in political activism?

Read, read, and read again while becoming active. In Britain and North America, I couldn’t advise them to join a political party of the Left because none exist. In Greece, I do recommend that working within Syriza is the best opposition, Podemos in Spain, and the Left Party in Germany, and that’s about it… otherwise, the Radical Independence Campaign in Scotland, Stop the War in Britain and other similar organisations elsewhere are the best transition to radical politics.

—

This interview was conducted by Al McKay. Al is an Editor-at-large of E-IR.