Japan’s Defense Trajectory: The Story So Far

The recent changes in Japan’s defense posture have been a long time coming. In a sense, they represent the natural continuation of gradual adjustments Japan has been making since the end of the Cold War (and in a sense, an evolution that has been occurring since the ratification of Japan’s postwar constitution). The most recent changes — the creation of the National Security Council, a slight bump in defense expenditures, revisions to the ban on arms exports, and the proposed reinterpretation of the constitution to allow for limited collective self defense — can be seen as a continuation of earlier modifications. As Corey Wallace has written, these changes represent an “evolution” rather than revolution in Japanese military affairs.

Following the embarrassment of the first Gulf War, where Japan’s hefty financial contribution was slighted, Japan became involved in U.N. peacekeeping. As the post-Cold War era progressed, Japan continued to gradually evolve in the area of defense: the revision of the U.S.-Japan Cooperation Guidelines in the mid-1990s, refueling assistance to NATO forces in the Indian Ocean through much of the Afghanistan campaign, the dispatch of the Self Defense Force to Iraq in the mid-2000s, the implementation of Ballistic Missile Defense, and adjustments to its weapons export ban. The idea of reinterpreting Japan’s constitution to allow for collective self defense in limited situations is not particularly new, either. In a sense, the move is an outgrowth of Japan’s evolving defense trajectory and various frustrations it has experienced as it has increased the use of the Self Defense Force in peacekeeping and for U.S.-Japan alliance management.

Broadly speaking, specialists on Japanese defense have been successful at defining this trajectory, mapping its basic course, and predicting these periodic changes. The story of Japan’s changing approach to defense has been variously called “reluctant realism” (Michael Green) and “transitional realism” (Daniel Kliman). Others, such as Richard Samuels, have pointed out that Japanese leaders have been engaging in a persistent campaign of pragmatic “salami slicing” of anti-militarist constraints on the use of force. Yet, in each successive slice, leaders have been careful not to stray too far from Japan’s anti-militarist identity. Generally speaking, whenever administrations have sought to reinterpret or modify anti-militarist institutions, there has been a corresponding pull to limit these revisions and to make them consistent with Japan’s anti-militarism. This pull has been the result of a combination of resilient anti-militarist institutions. These institutions include Article 9 of the constitution (which renounces war as a sovereign right), the three non-nuclear principles (the Diet resolution not to possess, manufacture, or allow the introduction of nuclear weapons in Japan), the one percent of GDP limit on defense spending (based on a Cabinet decision in 1976), domestic sentiments, and residual pacifist elements in Japan’s political system (such as the pacifist-leaning New Komeito, the Social Democratic Party, and pacifist politicians aligned with the two larger parties).

What is most remarkable about Japan’s approach to defense reform is not the break with postwar anti-militarism or any other radical changes, but rather how incremental and deliberate it has been, even in the face of growing Chinese capabilities.

Not all is well, however, and not everything can be described as running smoothly along this linear path. The difference this time has more to do with the ominous context of the actions (growing Sino-Japanese tensions and Chinese disputes with other actors over disputed territories) and the man behind the deeds (Prime Minister Abe Shinzo and his conservative political ideology) more than the actual content of the reforms.

This article looks at the three most conspicuous and worrying trends in Japanese defense policy and politics:

- the steep decline in Japanese-Chinese relations and the seeming collapse of a broad pattern of tension and reconciliation,

- the lingering potential for a more nationalistic Japan, and

- the dangers of minimal deterrence.

While each of these issues is an important one to monitor, there is no reason to believe that Japan will abandon its gradual approach to defense policy change anytime soon.

Declining Sino-Japanese Relations: Explaining the Collapse of the Tension and Reconciliation Cycle

The broad consensus that Japan is becoming gradually more realist in its defense posture is one that has held up well throughout the post-Cold War period. The idea that Japanese leaders were moving Japan toward more “normal” roles for their military alongside their U.S. partners, without trying to upset its neighbors, has proven to be an accurate description. However, another key idea, introduced in Richard Samuels’ Securing Japan was the idea of the “Goldilocks Consensus.” The idea, in short, was that Japanese leaders would be neither too hot nor too cold on a number of issues from defense and U.S.-Japan alliance rebalancing, but especially in balancing the sensitive triangular relationship with China and the U.S.

Indeed, “Goldilocks” seemed a good description for cycles of tension and reconciliation during the post-Cold War era. After the Tiananmen Square incident of 1989, China’s relations with Japan and other countries became fraught. However, Japan and China were able to mend their relations and Japanese Emperor Hirohito visited Beijing in 1992. Following the Taiwan Strait Crisis of the mid-1990s, where China used ballistic missiles and military exercises to intimidate Taiwan and influence elections, Japan strengthened ties with the U.S. through revision of the Guidelines for U.S.-Japan Defense Cooperation. The revisions increased the roles of the Self Defense Force within the alliance structure and included language that committed Japan to provide rear-area logistical support to U.S. forces in the event of contingencies “in areas surrounding Japan.” These new commitments seemed to imply that Japan would provide assistance in the event of an incident involving Taiwan. Though the language was vague, the implied aspects of the new guidelines infuriated China. However, Japan, under the leadership of Hashimoto Ryutaro, was able to pivot from his success with the U.S. to improve ties with China soon after.

Later, when ties between the U.S. and Japan experienced a renaissance during the Koizumi Junichiro administration, ties with China plunged into what was then a new low. Much like the current situation, the mid-2000s witnessed multiple crises over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, public demonstrations in China directed against Japan, and a terse relationship between leaders. This atmosphere was due in no small part to Koizumi’s insistence on visiting Yasukuni Shrine. However, ties then improved during the first administration of Abe Shinzo in 2006, culminating in a joint statement calling for efforts to build a “mutually beneficial relationship” based on common interests and a number of initiatives to ease tensions between the two countries, such as an agreement for a joint development zone for gas reserves in the East China Sea and even a three-year joint historical study.

Here we see a theory working at its best. Samuels’ “Goldilocks” approach seemed to demonstrate something that was counterintuitive, a Japanese leader of conservative leanings putting aside his ideology to improve ties with China after a period of extreme tension. In a sense, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) was supposed to be a continuation of this Goldilocks logic. The DPJ, it was thought, would strengthen ties with China after years of over-emphasis on the U.S. bilateral relationship. Instead, under the DPJ and now during Abe’s second administration, relations with China have found new low points – new escalations in tensions over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, mutual recriminations by politicians, violent protests in China, and a collapse in public opinion of the other country on both sides – without any sign of readjustment.

These events prompt two important questions: What accounts for the collapse of the tension and reconciliation cycle? And is there another round of reconciliation on the horizon?

Most answers to the first question put varying emphasis on three types of variables: structural change, DPJ amateurism, and Chinese opportunism.

Certainly realists of various schools would note that a drastic swing has taken place in the balance of capabilities. While Japan’s defense expenditures alone in the mid-90s are estimated to be twice those of China’s (see Stockholm International Peace Research Institute figures), by the mid-2000s, at least in terms of expenditures, China had overtaken Japan. Currently, China spends more than double Japan does on defense. Admittedly, these figures are crude. They do not take into account the opacity of China’s military buildup, the unreliability of measures of Chinese defense spending, and they overlook issues such as relative technological advantages, the quality of military training, and the advantage Japan has with the U.S. as a defense partner. These figures also do not look at the relative capabilities of law enforcement forces that are charged with policing the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. At the very least, China’s growing submarine fleet, missile capabilities, as well as its ability to project power in Japan’s Exclusive Economic Zone and international waters are areas of concern.

Recent events in Japan and the U.S. have only exaggerated these larger structural trends. Typically 2008 is depicted as a watershed year — a year when China demonstrated its competence through the Beijing Olympics and the sharpest onset of the financial crisis occurred. Since that time, both the US and Japan have been more focused on domestic and economic issues than international affairs. Both countries have suffered from domestic political turmoil that has weakened political leadership at critical times and created the permissive conditions for more aggressive Chinese action. Successive budget crises have given the impression that U.S. resolve is lacking and that domestic issues now dominate. In Japan, the rapid succession of weak prime ministers has also potentially emboldened China. The financial crisis has shifted the relative balance of confidence and opportunity China’s way. In 2010, China finally surpassed Japan as the world’s second largest economy. In this context, China has become more assertive in relations with Vietnam and the Philippines in the South China Sea, has stepped up its campaign to challenge Japan over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, and has unilaterally declared an Air Identification Zone overlapping the Japanese one in the East China Sea.

A second important cause might be termed “DPJ amateurism.” After years of domination by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), the Democratic Party of Japan came to power in a sweeping victory in 2008. The party promised to create a more “balanced” U.S.-Japan alliance, improve ties with China, and support East Asian integration. However, after a long period in opposition, the party was long on promises and ideas and short on practical policy experience. During the DPJ administration, steps were taken to improve Sino-Japanese ties, most notably a historic visit by 143 Diet members and other party members to Beijing and the appointment of the first non-foreign service ambassador to China – Niwa Uichiro, a businessman with formidable experience in the China market. However, the bigger story was the slide first in relations with the U.S. and then later with China.

Three events in particular over the course of the DPJ’s time in power bear mentioning. The first is Prime Minister Hatoyama’s handling of the Futenma Airbase issue. For many, the conflict between the U.S. and Japan over the details of the base relocation seemed to have emboldened China. The second is Prime Minister Kan’s capitulation to China in returning an arrested ship captain to China after a Chinese trawler deliberately rammed a Japanese Coast Guard patrol vessel near the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. Since the return occurred after China decided to cut rare earth metal exports to Japan, the decision to return the captain seemed like Prime Minister Kan was yielding to a Chinese demonstration of power and purpose. An important aspect of the event was the uploading of a video on YouTube showing the trawler ramming the Coast Guard vessel. The video stoked Japanese nationalism and intensified the sense of embarrassment when Kan decided to return the ship captain. The third was Prime Minister Noda’s decision to purchase three of the five islands to keep them out of the hands of nationalist politician Ishihara Shintaro, who planned to incorporate them into the Tokyo Metropolis and build wharves and lighthouses on them.

Unsympathetic commentators will be more scathing in their evaluation of DPJ leadership missteps and failures, pointing to their naivety and their inattention to reality. Opponents of the DPJ can variously point to the failure of Hatoyama to maintain a strong alliance with the U.S. and credible deterrence, the failure of Kan to stand up to Chinese bullying, or Noda’s bungling of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Island purchases. Those with more sympathy for the DPJ are more likely to point to bureaucratic intransigence, the persistent influence of the “U.S. lobby,” and the shift away from a pro-China policy under Kan or Noda. In addition, one can also debate the degree to which each actor mishandled the situation. Should Kan have continued to detain the ship captain? Was Noda right to purchase the islands? Would the situation have been even worse if Ishihara Shintaro had been allowed to purchase them? Untangling these questions and leaving one’s own preconceptions at the door is no easy task. What is often missed in descriptions of the DPJ’s defense policy is how relatively consistent it was, despite these three focal events. Successive DPJ prime ministers chose, for the most part, to maintain U.S. extended deterrence, to continue to improve Japanese military capabilities within strict budgetary limits, and to revise the defense export ban to facilitate cooperation with other countries. In addition, during the DPJ, and particularly as a result of the 2010 incident regarding the ship captain during the Kan administration, Japan became more pronounced in its public documents in addressing the military threat from China.

Finally, Chinese opportunism seems to be an important cause. Much like the second cause under discussion, how one interprets Chinese actions will depend on one’s particular point of view. Is China’s assertive actions toward Japan (and the Philippines and Vietnam) based on misunderstandings, a result of provocations by its neighbors, or part of a long-term strategy of exploiting opportunities to change the status quo?

For many, the period from 2008 onward represents something new in terms of Chinese opportunism. Mohan Malik refers to this as a transition in the post-2008 financial crisis era from “hide and bide” to “seizing opportunities.” An International Crisis Group report describes this as “reactive assertiveness,” China’s strategic use of “perceived” provocations by other countries in disputed areas to change the status quo in its favor. This pattern was demonstrated not only in the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands, but also in the Scarborough Shoal against the Philippines, and the Spratly and Paracel Islands against Vietnam. In short, Chinese leaders feel they have no reason to keep relations with Japan “just right,” and have much to gain politically by keeping the temperature up. Some venture that China may be looking to take back the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in a short, sharp war. Since the 2012 nationalization of three of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, Japan has suffered a number of incursions into the area: over twenty in 2012, and over fifty in 2013.

Certainly, this thesis is challenged by those who find a great deal of consistency in Chinese behavior. Björn Jerdén, for example, finds that recent actions have been largely consistent with prior actions. Even Jerdén, however, finds that analysts who stress Chinese assertiveness since 2008 and 2009 are more forgetful of past assertiveness. In other words, there was clearly no lack of Chinese assertiveness during the post-Cold War, and that this is merely the continuation of a pattern. Yasuhiro Matsuda presents the most exhaustive study of China’s recent behavior and asserts “cautiously that China’s assertiveness is indeed reactive” — that China tends to “cherry pick” events to fit its strategic objectives and paint Japan as in danger of remilitarization.

No doubt, my own judgement of recent history is subject to bias and a selective reading of events, but I tend to put more weight on the first and third causes (structural changes and Chinese assertiveness) and minimize DPJ amateurism. In terms of the third cause, perhaps it is difficult to say with certainty whether, on the whole, China is more assertive or less assertive than other periods. However, its improved capabilities and rising confidence in relation to the perceived declining powers of Japan and the U.S. nonetheless make its policies seem all the more threatening. More importantly, improved capabilities and confidence give China less reason to moderate its actions or to seek the amelioration that was seen during the first Abe administration. In its place, we have progressive tension-building short of war. In the future, China will most likely continue to cherry pick aspects of Japanese politics to use for great levels of tension that it can use for domestic reform and assertiveness on territorial issues.

It may be that my judgement is wrong and that another cycle of reconciliation is coming. This would be a welcome turn of events. However, since the current period of tensions is significantly longer and more intense than prior periods, and is driven by events more central to Sino-Japanese relations, it seems that the next amelioration cycle will most likely be more limited, focused on short-term crisis management. My own judgement is that this amelioration will not provide a framework for long-term peace unless the U.S. and Japan can genuinely make deterrence credible again.

Rethinking Japanese Nationalism: The Nationalist Turn that Did Not Happen

Almost as talked about as the deterioration of Sino-Japanese relations has been Japan’s shift to the right, a topic that has been the subject of much popular news. Japan is indeed moving to the political right, and the ideology and historical opinions of a more emboldened Abe Shinzo (as opposed to the pragmatic Abe Shinzo of 2006-2007) make that nationalism more worrying. So far, Abe’s nationalism has been most conspicuous in his one visit to Yasukuni Shrine (as opposed to the yearly visits by Koizumi) and for things that were teased but have yet to occur, such as a revision of the Kono Statement and Murayama Apology. A more hardline approach to history may still be yet to come, but so far the personality of Abe Shinzo and his occasional gaffes have been more ominous than his policies.

However, in the run up to the 2012 election, there were moments when the story could have been much different. At that time, a new grassroots movement started in Osaka by Hashimoto Toru had grown into a national movement, the Japan Restoration Party, and was drawing support from the large number of people who were disillusioned with both major parties. This party soon merged with another party led by the popular ultra-conservative politician Ishihara Shintaro. For a moment, it seemed that a much more radical politics was in Japan’s future — one that was far more nationalistic and harder to predict. A stronger prime minister? A weaker Diet? A wholesale revision of the constitution? A nuclear Japan? An unwinding or sharp break in the U.S.-Japan alliance? These were all possible aspects of Japan Restoration Party’s movement.

Large changes at the international level, DPJ blunders, and Chinese opportunism were all part of these new radical impulses; however, at the heart of the matter were Japan’s lingering domestic problems and the need for national self-confidence.

At the time, the party was still a “third force” in Japanese politics; however, there was the chance that a successful election might draw in conservative elements from other parties and lay the groundwork for a coalition with the LDP, or perhaps a bigger electoral success down the line. Toward the end of the election cycle, political gaffes and tensions in the ideologies of Hashimoto and Ishihara led Japan Restoration Party to slip and Abe’s LDP to claim a stunning victory. The recent failure of Japan Restoration Party to merge with another small party and the recent split-up of its two biggest personalities means that, at least for the time being, a transition to a more radical right wing politics has become less likely.

One should not forget that a more radical turn is still possible. For the moment, Japan is buoyed by a sense of optimism in Abenomics, and Prime Minister Abe has shown enough of his earlier tendencies toward pragmatism and moderation (continuously tempered by his political partner, the New Komeito, and his strategic partner, the US) to stabilize domestic politics and foreign relationships. Thus, up until now, his nationalism has served as a kind of inoculation against more fervent nationalism. However, Japan’s domestic problems are deep and its external security situation is still a concern. The failure of competent left-wing political actors to emerge is also part of the evolving story and increases the potential for a nonlinear break away from Japan’s usually gradual approach to policy change.

Thus far, Japan has gotten mostly the best of the two Abes – the Abe that is pragmatic and measured in geopolitics, and bold in economic policy. The hints of a more ideological Abe, however – an Abe who visits Yasukuni Shrine and probes the boundaries of the Kono and Murayama apologies – are a worrying sign that a bigger right wing transition is still possible.

Mapping the Uncertain Future in Japanese Defense Policy

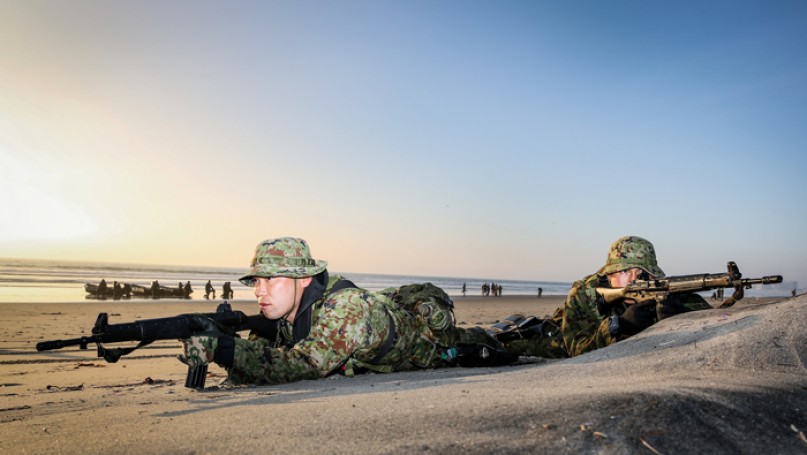

Japan has been following a deliberate course in the reform of its defense policy. This program has emphasized gradual change over revolutionary breaks. More changes are certain to come. In the future, we can expect increasingly elaborate joint military exercises aimed at deterring specific kinds of threats from China; the loosening of restrictions to allow for greater interoperability with U.S. forces; continued rationalization and modernization of the Self Defense Force within the one percent of GDP budget limit; increasing defense cooperation with countries that fear Chinese assertiveness in maritime disputes, including expanded ties with ASEAN, Australia, and India that include defense consultations; expanded help to countries facing maritime threats from China such as Vietnam and the Philippines through ODA policy; increased joint weapons development with countries other than the U.S.; and political moves that raise the profile of the U.S.-Japan security relationship.

The threads that tie these various moves together are gradualism, continuity, and thrift. Even in the face of growing Chinese capabilities (and North Korean provocations), Japan will most likely avoid acquiring their own nuclear deterrent, forming formal alliances with third countries, or eclipsing its one percent of GDP limit on defense spending.

If these policies are wise and pragmatic, they also might be too cautious.

Whether these gradual moves will keep deterrence credible or what new actions can be expected from China’s “reactive assertiveness” is still an open question. As Chinese capabilities rise, U.S. and Japanese resolve will be tested more regularly. These Chinese provocations may be telling us something very important – the status quo cannot hold. The simple reason behind this might be that what once was sufficient deterrence is becoming, or at least being interpreted as, insufficient.

Many stories of the outbreak of war are also stories of the failure of deterrence. All stories of the outbreak of war have their own particular rationale stemming from history, geography, and leader calculations, but in many there is a basic generic outline. As new powers rise, dissatisfied with the status quo and bristling with memories of past slights and dishonor, entrenched and satisfied powers are slow to dissuade and deter, either through a combination of fatigue, complacency, or preoccupation with domestic problems. (The failure of minimal deterrence is a central theme throughout Donald Kagan’s The Origins of War).

The U.S. and Japan are already straddling a fine line between pragmatic and complacent.

As this article has attempted to show, the basic trajectory of Japanese defense has already been defined well by policy experts. For this reason, what is needed most from Japanese scholars is not more formulations of this basic trajectory, but rather an exploration of potentials: What is the likelihood of a more nationalistic turn? What is the sequence of events that can bring it about? How can Japanese leaders – especially those of rightward leanings – be persuaded to abandon their obnoxious views of history? How can leaders on the left be persuaded to embrace military realism and the U.S. alliance? What focal events and shocks could radically shift Japan’s defense orientation? What kinds of resources would make deterrence toward China credible again?

These are the questions that will drive the study of Japan’s defense policy and politics forward.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Max Nurnus for his comments on numerous drafts of this essay. He wouldn’t have been able to complete the essay without his help. All errors and omissions, of course, are solely the responsibility of the author.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Transnational in China’s Foreign Policy: The Case of Sino-Japanese Relations

- Evolution of Sino-Japanese Relations: Implications for Northeast Asia and Beyond

- A Pessimistic Rebuttal: The Eventual Return of Sino-Japanese Tensions

- Statue Politics vs. East Asian Security: The Growing Role of China

- The Incremental Revolutionary: Japan after 8 Years of Shinzo Abe

- Opinion – Shinzō Abe and Russo-Japanese Relations