The August 2014 presidential elections in Turkey constitute a new turning point in its modern history. According to the election campaign’s ideological framework, but also in line with recent developments in the country, the result of the presidential election has serious effects on the Turkish political system and society at large. At the heart of all this is the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), becoming the establishment in the country, the prevalence of the political agenda for a “new Turkey”, and the prospect of a political change with the adoption of a presidential system or semi-presidential one. This text seeks to decipher the essence of the “new Turkey”, from the viewpoint that this is the AKP’s and Erdoğan’s main policy objective. At the same time, it tries to explain the concept of the “new Turkey” as a result of the hegemonic position AKP has already gained in Turkey. Finally, the article analyzes the relationship between political Islam and the presidential system, a relationship that is one of the key issues in the election.

Theorising the “new Turkey”

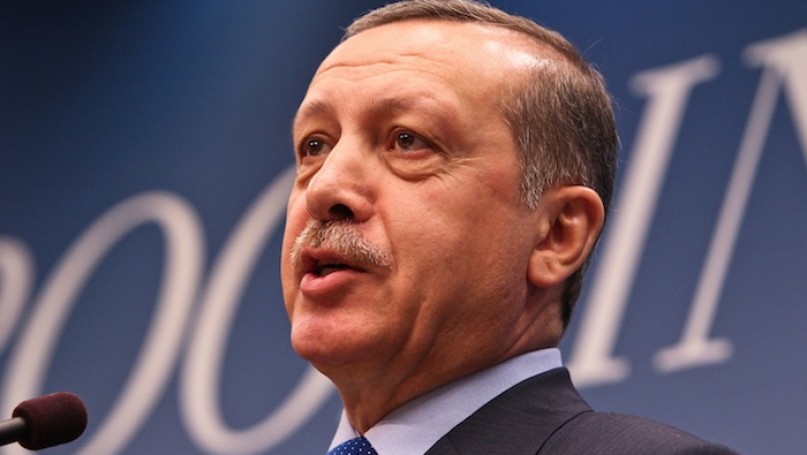

“This moment is not a farewell, not the end… It’s a fresh start… It’s a Fatiha, it is a new beginning.” [1] With those words, the Turkish Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan concluded his speech at the launch event of his presidential candidacy on 1 July 2014. At this juncture, the use of the term Fatiha was not random. Al-Fatiha is the first chapter of the Koran, but at the same time considered the “opener” of the Moslem holy book, which includes the centre-piece of the Islamic religion. Therefore, the political importance of the use of this term by the Turkish Prime Minister goes beyond the simple religious message. It refers to a “new” page being turned in Turkish history, the beginning of the construction of Erdoğan’s “new Turkey”. It clearly refers to an alternate “founding moment”, which is distinguished by Erdoğan’s manifestation as the country’s 12th president.

What, then, is the meaning and contents of the “new Turkey” as the basic theoretical and political background of Erdoğan’s candidacy? The construction of national history is, among others, an act in which the nation-state proclaims itself both as the key author, as well as the fundamental actor of this story. In this context, the historical legitimacy and recognition of the state require a “founding moment” (Çınar 2001: 365). That is, the moment when the state takes its position at the forefront of history, signalling both the “new beginning” of the nation and determining its “official” past.

Feroz Ahmad, in The Making of Modern Turkey, includes two chapters entitled “The new Turkey” (1993: 52-102), in which he assesses the political and socio-economic developments in the 1923-1945 period. Turkey’s transformation process is analysed as it took place after the war of independence. Ahmad explains how Mustafa Kemal and his movement gradually imposed strict secular definitions of the nation, rational laws regulating the state, as well as state capitalism. The Kemalist state’s “founding moment” sought to extinguish the imperial past and prevent Ottoman history from being conserved as a structural part of Turkish-secular national identity. It was no coincidence that the Kemalist elite chose 29 October 1923 as its “founding moment” and National Day, when the National Assembly proclaimed the independence of the new state. The composition of this National Assembly, in contrast to that of 1920 (Kili 1982: 66-69), almost entirely conveyed Turkish national “uniformity” centred on secularism and the Kemalist leadership’s republicanism.

Today, deciphering the Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) Fatiha and its objective of a “new Turkey” clearly points to the challenging of the Kemalist reading of national history. It centres on the prospect of ideologically contesting the Kemalist nation-state itself (White 2013: 8). At the same time, it questions the “Kemalist” homogeneity of the nation and therefore of the state itself and its power. Erdoğan’s “new Turkey” entails a new state, a new historical power block, including a new make-up in the army and the judiciary, and a new balance between the different elements of the bourgeoisie. At the same time, AKP’s new historic bloc carries with it is “own” organic intellectuals, media, universities, and civil society organisations. AKP’s “new Turkey” ought to be characterized by new social relations in the context of neoliberalism, increased urbanisation, and the influences on the country by regional and international developments. Finally, the “new Turkey” that Erdoğan’s presidency promises is shaped by Islam, which is not only more visible in the public sphere, but is a key structural element of national identity and society’s collective expression.

Long-term domination

One of the most important changes in Turkey in recent years has been that the rise and strengthening of the religious-conservative elite has questioned the social and political supremacy of the secular branch of the bourgeoisie. The AKP and the social forces that rally around it have gradually imposed a new “unorthodox” concept of “Turkishness”, which now dominates in all spheres of social relations (White 2013: 9). The neoliberal reforms of the past 30 years are now accompanied by the reconstruction of a glorious Ottoman-Islamic past, which is being restored as society evolves daily. The Ottoman past and Islamic values have transformed themselves into key components of Turkish identity and become the principal “certification” of the values, ethos, and substance of the “millet-nation”. These “nationalised” versions of the Ottoman tradition and the Islamic religion have become elements of the establishment’s everyday public discourse, and are being accepted and comprehended by the wider masses. Thus, they have all-powerful “symbolic power” in their hands, as explained by Eric Hobsbawm.

The “new Turkey”, as the centerpiece of Erdoğan’s political programme, encapsulates the aim to consolidate all the changes the country has experienced in recent decades, while legitimising the AKP’s hegemonic position. The ruling party is the result of Turkey’s transformation, but on the other hand it is also its principal vehicle and driving force. The transformation underway is multidimensional, with manifold factors and forces that touch on all spheres of social activity, expanding from economy and culture to regional and international relations (Keyman 2014: 25). Therefore, AKP’s hegemonic position itself is not static. It incorporates features that weaken the opposition, expanding the social core of the party’s support base and its ability to govern both at national and local levels (Gümüşçü 2013: 230-240). As AKP consolidates its power, it is simultaneously transforming Turkey (Keyman, Gümüşçü 2014). Furthermore, the continuous electoral successes from 2002 until the March 2014 municipal elections and the August 2014 presidential elections have created an “electoral hegemony” that tends to convince the public that the opposition can never win. In this sense, Erdoğan’s prevalence in the upcoming presidential elections should not be surprising, nor should a new AKP victory in the 2015 general elections. In short, if the crisis on a worldwide level and Turkey’s internal balances continue as is, the AKP may very well be able to maintain its basic power base within the establishment until at least 2019.

“The presidential system is in our genes!” The conservative legitimisation of change

According to the AKP’s and others’ traditionalist view of Islamic parties and the National Outlook Movement (Milli Görüş Hareketi), Turkey was for years dominated by the Westernised – therefore foreign to the Muslim millet – secular elite. That is, the Turkish secular state created a situation that bred animosity between the state and the Muslim millet-nation.

In this context, the objective of the Islamic tradition was the “reunion of the state with its own nation”, the prevalence of a historic reconciliation and power embracing the Muslim millet: in short, the transition of power into the hands of the “genuine representatives” of the nation-millet. The AKP now seems to reproduce the perception of conflict between state and nation, albeit updated to the new socio-economic context. As a continuation of the above historical interpretation, the problems in the political system and especially the Constitution emanate from its top-down enforcement, thus circumventing national will (Kuzu 1996: 75), the will of the original Muslim millet. Thus, political Islam’s “holy” mission to solve the above problem focuses mainly on two areas: the creation of a Constitution that does not circumvent the will of the nation-millet, as well as a commitment to a Constitution whose contents will highlight all that which will re-establish Turkey as a “glorious state” inspired by the Ottoman imperial legacy. For example, the referendum as a political act has a strategic significance within the above ideological framework. Through the referendum, democracy is safeguarded, entailing the participation of the nation-millet and promoting the historic reconciliation between this millet and the “alienated” state (Teazis 2010: 60). During its twelve years in government, the AKP had overseen two referenda on constitutional change.

Moreover, the Constitution itself must not only meet the needs of the new socio-economic and political development in Turkey, but also the foreign policy requirements such change has brought. The country’s Constitution should facilitate the elimination of the traditional, and in many ways “fake” national borders, and open the way for broader integration in the region. As Şaban Abak notes in the newspaper Yeni Şafak, the creation of a new Constitution should ensure the prospect of embracing neighbouring peoples and ensuring that the process of integration with/in Turkey resumes. Therefore, the new Constitution should constitute a departure from the state of affairs established at the end of the First World War, restoring within a new context the experience of the Ottoman Empire. At this point, the concept of “Glorious State” (Kerim Devlet) enters the frame, which will become a point of reference and a source of inspiration for the neighbouring peoples.

In a state such as this, in an environment of a restored “greatness”, whereby Turkey can incorporate its neighbouring area into the neo-liberal framework, the presidential system is “fitting”. The reasoning is that the presidential system, according to this approach of political Islam, is a characteristic safeguard of “great, glorious and developed states.” Erdoğan meaningfully notes that:

The presidential system is not foreign to us. Our ancestors lived through something similar during the Ottoman Empire. This system exists in the most developed countries of the world. The USA and Russia have presidential systems. In France there exists a semi-presidential system. In Latin America also. If developed countries are thus administered, then it means something.

These statements take on a particular meaning, if one considers that the presidential system is used as being synonymous with economic growth and therefore the “greatness” of the state. At the same time, the change in the political system is exalted as a cultural necessity, which is appropriate for the country and the nation-millet.

In this sense, the August 2014 presidential elections take on strategic importance for the future of Turkey. For the first time, the country’s president is elected directly by the people in accordance with the 2007 constitutional reform. The popular legitimacy offered by the process de facto pushes Turkey towards a peculiar semi-presidential system. This peculiarity stems from the lack of a precise constitutional change and formal adoption of a presidential system. However, the combination of enhanced presidential powers, as had been provided for by the 1982 Constitution, together with a direct popular mandate, makes the next President a critical determining factor in the construction of the “new Turkey” that is emerging.

The above applies multiples times in the case of Erdoğan, who has indicated that “he will not be a ceremonial president, but a president who will run and sweat.” In this way, he established the characteristics of the presidency in the new Turkish era. This statement, as well as other recent developments in the country, is characteristic of the flurry of activity that will culminate with the August presidential elections as another step that will determine Turkey’s future, possibly for the next decade. The presidential elections, in conjunction with the fight that will take place with the 2015 general elections (if these will take place as presumed), are developments that mark two long-term processes: The first is reinstating the conflict around the principle position of political Islam, which is the change in the political system of Turkey. Therefore, the structure as well as the protagonists in power after these two crucial elections will be constituent elements of a new regime in the country. The second process is the strengthening of its foreign policy on the basis of a “post-Western world” ideology of AKP.

Bibliography

Ahmad, F. 1993.The Making of Modern Turkey. London & New York: Routledge.

Çınar, A. 2001. “National History as a Contested Site: The Conquest of Istanbul and Islamist Negotiations of the Nation.” Comparative Studies in Society and History, 43/2: 364-391.

Gümüşçü, Ş. 2013. “The Emerging Predominant Party System in Turkey.” Government and Opposition, 48/2: 223-244.

Keyman, F. 2014. “The AK Party: Dominant Party, New Turkey and Polarization.” Insight Turkey, 16/2: 19-31.

Keyman, F. Gümüşçü, Ş. 2014. Democracy, Identity, and Foreign Policy in Turkey. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Kili, S. 1982. Türk Devrim Tarihi. İstanbul: Tekin Yayınevi.

Kuzu, B. 1996. “Türkiye için Başkanlık Hükümeti.”Amme İdare Dergisi, 29/3: 57-85.

Teazis, C. 2010. İkincilerin Cumhuriyeti. Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi. İstanbul: Mızrak Yayınları.

White, J. 2013. Muslim Nationalism and the New Turks. Princeton & Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- An Ontological Reading of Turkey’s AK Party – Gülen Movement Conflict

- Protests in Turkey Amid a Global Shift to the Right

- Opinion – Turkey’s May Elections Are about Regime Change

- Opinion – How the West Can Prepare for a Post-Erdogan Era in Turkey

- Deciphering Erdoğan’s Foreign Policy after Turkey’s 2023 Elections

- Religion and Secularism in Turkey, and The Turkish Elections