Iran’s influence in Latin America and its national security implications has finally caught the attention of U.S. policy makers in Washington, D.C. What are Iran’s interests in Latin America? But, most importantly, what are the national security implications for the United States? What are the options for the U.S. Government? Iran’s relations with Latin America date back to the 1940s, when Iran and Venezuela united to call for a better treatment from international oil companies, however, it is only in the 2000s that great diplomatic relations began to be noticed by the international community with some degree of fear regarding the objectives of such a close relationship.

This greater interaction would go unnoticed had it not been for the partnerships established between Iran and some of the Latin American countries. Ahmadinejad’s political goal was to establish a policy toward Latin America that was anti-American. As Ahmadinejad has publicly stated, “Tehran is pursuing a strategy that promotes its own ideology and influence in Latin America at Washington’s expense” (Berman 2012:63-69). This anti-American foreign policy creates what the late Hugo Chavez referred to as “the axis of unity” foreign policy against the United States and its imperialist foreign policy. In one of his many trips to Latin America in 2009, the Chavez welcomed Ahmadinejad, referring to him as a “gladiator of anti-imperialist struggles” (Arnson, Esfandiari & Stubits).

In the words of one long-time observer of American foreign policy, “Iran may well be the most important, and at the same time the most complex and the most volatile, of all the foreign policy problems with which the United States must deal” ( Wiarda 2011:122). Ilan Berman, during his testimony on July 9, 2013, to the U.S. House of Representatives Homeland Security Committee Subcommittee on Oversight and Management Efficiency, stated that “Iran’s strategic presence in Latin America constitutes a potential threat to American security. Yet, to a large extent, this challenge remains poorly understood by the U.S. government as a whole, while the Executive Branch in particular has been hesitant to truly examine and address it” (Berman 2013).

Iran’s Interests in Latin America

Isolated by the West (i.e. United States and some European countries) and sanctioned by the U.N. Security Council for its nuclear program, Iran is a rogue state in the international community. Therefore, the question becomes: why is Iran and its Supreme Leader, Sayyid Ali Khamenei, shifting its foreign policy from the Middle East toward Latin America? What are the objectives of this foreign policy shift from the Islamic Republic of Iran’s perspectives?

In its Annual Report on Military Power in Iran released April 2012, the Department of Defense stated that Iran is seeking to increase its stature vis-à-vis the United States by influencing and expanding its ties with regional actors while advocating Islamic solidarity. The report goes on to state also that Iran desires to expand economic and security agreements with other nations, especially members of the Non-Aligned Movement in Latin America and Africa. Iran’s foreign policy expansion is aimed at enhancing its economic, political, and security ties with a range of countries, demonstrating Tehran’s desire to offset its diplomatic isolationism from the international community (DoD 2012).

Iran’s newly elected President Hassan Rouhani, a moderate Shiite cleric often referred to as the “diplomatic mullah” due to his long diplomatic experience, during his inaugural speech stated that he intends to continue the foreign policy objectives of his predecessor when it comes to Latin America. President Rouhani plans to pursue constructive relations with the international community, improve Iran’s economy, and resolve the nuclear issue. President Rouhani has also publicly stated that “Iran has never sought war with the world and we will focus on stopping those who seek war.” He further stated that Iran intends to expand its foreign policy in Latin American and Cuba is a key diplomatic and political ally in the process.

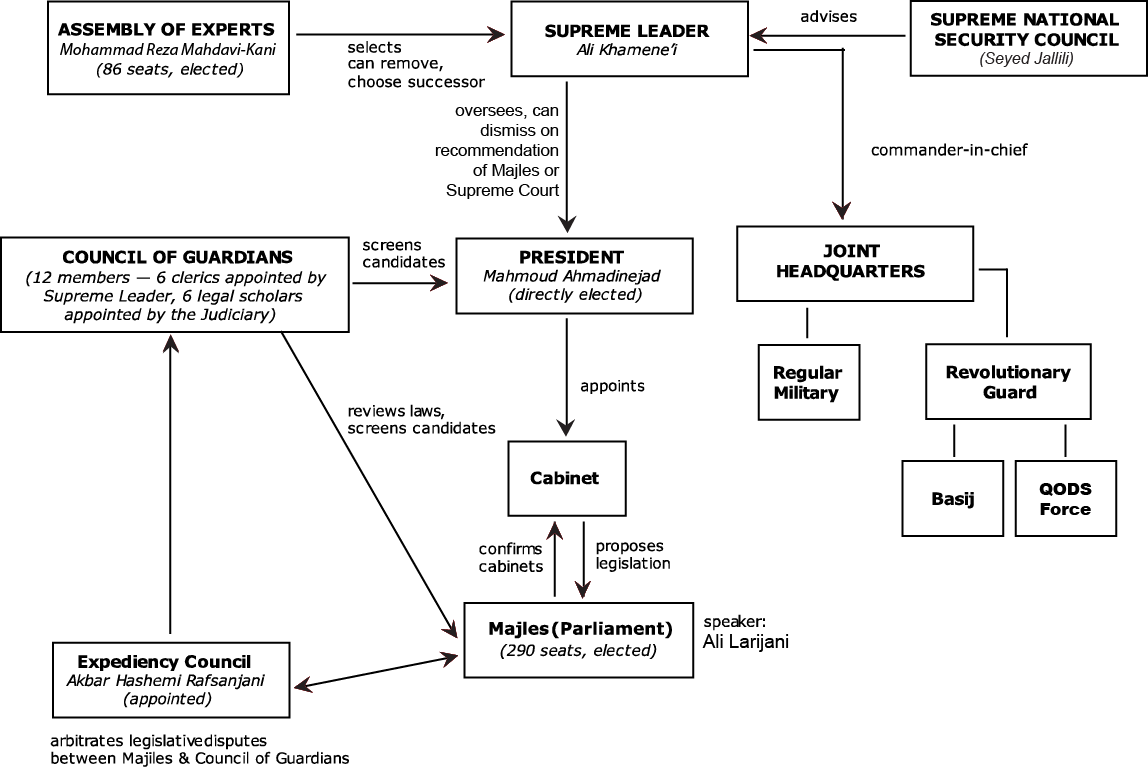

Iran Supreme Leader Sayyid Ali Khamenei has also endorsed Iran’s closer proximity to the Non-Aligned Movement nations in Latin America. In his speech at the 16th Non-Aligned Summit on August 30, 2012, Ali Khamenei stated that “current global conditions provide the Non-Aligned Movement with an opportunity that might never arise again.” This endorsement by Iran’s Supreme Leader is not only important for its symbolism, but also because the Supreme Leader is commander in chief of the armed forces, controls intelligence apparatus, and sets the direction of foreign policy (See Figure 1) (Misztal 2013). Elodie Brun argues that Iran’s diplomatic mantling in Latin America has been facilitated as an “outgrowth of the mounting criticism among Latin American governments of U.S. foreign policy, providing an easy opportunity for Iran to make connections in Latin America” (Brun, 15). Since U.S. foreign policy is threat-driven and Latin America does not constitute a threat to U.S. national interests, the U.S. does not pay the necessary attention to the region until a threat arises.

In light of this shortsightedness by the U.S. policy-makers regarding Latin America, former Iranian President Ahmadinejad and current President Rouhani have been seeking support to counter U.S. and European “pressures to stop Iran from developing nuclear capabilities” in the U.S.’s backyard (Karmon 2010). According to Farideh Farhi, Ahmadinejad’s regional approach to Latin America was composed of three key objectives: continuation and expansion of bilateral strategy with key Latin American nations, especially Brazil; a highly publicized touting of the relationship with Venezuela and the creation of the so-called “axis of unity” between Iran and its major partners in Latin America, espousing an anti-American foreign policy posture despite Latin America’s heavy dependency on the U.S. as a trading partner; and, finally, a highly publicized relationship with the new governments of the smaller countries of Bolivia under the leadership of Evo Morales, Nicaragua with Daniel Ortega, and Ecuador under Rafael Correa (Farhi:29-30). In summary, Iran’s foreign policy toward Latin America can be seen not only as antagonistic toward the U.S. and its national security interests, but it also fulfills Iran’s attempt to establish a great presence in the U.S.’s backyard [1].

Iran’s Latin American Partners

Iran’s Latin American partners are part of the so-called “pink tide” that came to power between the years of 1998 and 2009. The “pink tide” nations are united by their strong resentment and anti-American sentiment. Despite the fact that the “pink tide” did not have a clear-cut ideology, they were united in opposition to the Washington Consensus [2], a laundry list of demands imposed by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reminiscent of Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress (Wiarda 2012: 18), to rescue the economies of the “pink tide” countries during the “lost decade.”

Another common denominator uniting the “pink tide” nations is their foreign policy of soft balancing. According to Javier Corrales and Michael Penfold, soft balancing refers “to nations’ efforts, short of military action, to frustrate the foreign policy objectives of other, presumably more powerful nations; a variation of traditional balancing behavior, the concept is a core tenet of realism” (Corrales & Penfold, 2011:11). No other country in Latin America is more representative of this antagonistic foreign policy behavior toward the U.S. than Venezuela under the leadership of the late Hugo Chavez.

Venezuela’s closer proximity to Iran and Iran’s infiltration on the U.S.’s backyard has been a cause for concern among government officials in the U.S. According to Roger F. Noriega, Venezuela is waging asymmetrical warfare against the U.S. and its allies using

cocaine, criminality, and the nuclear wild card. Chavez has committed the Venezuela state to help Iran develop nuclear technology, obtain uranium, evade UN sanctions, smuggle arms and munitions, and carry out a host of other shadowy deals under the nose of the United States.

Another country that has benefited from closer proximity to Iran while the U.S. has been entangled in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and now Syria while ignoring Latin America, is Nicaragua. During President Ortega’s visit to Tehran in 2007, President Ortega “called for establishing a new world order and supplanting capitalism and imperialism”. President Ortega is also one of the key leaders and proponents of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our Americas (ALBA). The ALBA is based on the “promotion of cooperation and preferential trade agreements with selected nations which share the political orientation of the Venezuelan government” (Giacalone 2013:304). The ALBA is a socially oriented trade bloc bent on eradicating poverty.

Bolivia has become an important strategic partner in Iran’s efforts to influence leftist governments in Latin America. Bolivia and Iran have signed a series of cooperation agreements making Iran a partner in the mining and exploitation of Bolivia’s lithium, a key strategic mineral with application for nuclear weapons development (Berman 2012:63-69).

Pursuing a policy of energy independence from sanctions imposed by the U.S. and the European Union, Iran has also approached another developing country in Latin America: Ecuador. Why Ecuador? Ilan Berman argues that Iran appears to be eyeing Ecuador’s uranium deposits. Iran’s entanglement in Ecuador’s natural resources obviously presents a major challenge to the U.S. “Latin America could emerge in the near future,” according to Ilan Berman, “as a significant provider of strategic resources for the Iranian regime and a key source of sustenance for Iran’s expanding nuclear program” (Berman 2012:63-69).

Another key player in the Bolivarian Revolutionary movement is Cuba. Cuba has had a long-standing diplomatic and economic relationship with the Islamic Republic of Iran and Cuba has routinely been included in Ahmadinejad’s several trips to Latin America. Iran’s cozy relationship with Cuba is a cause of concern since, pursuant to Section 6(j) of the Export Administration Act 1979 (EAA), the Department of State has placed Cuba among its lists of states sponsoring terrorism since 1982, along with other states such as Iran, Sudan, and Syria. Particularly concerning to U.S. policy makers are statements made publicly by both Cuba’s leader Fidel Castro and his counterpart, Iran’s former President Ahmadinejad, expressing their desire to fight “big powers by the day.” The so-called “big powers” are the U.S. and its European allies, and their imposition of economic sanctions against Iran for violation of the non-nuclear proliferation treaty. In its efforts to assist Iran in accomplishing its objectives in Latin America, Cuba has taken several steps in this new wave of revolution and increased cooperation between the two nations. For example, it has been reported that Iran has used an electronic jamming station outside of Havana to jam the broadcasts of Iranian dissidents based in Los Angeles and elsewhere in the United States (Katzman:56; Hughes 2006:9). Cuba has also assisted the Tehran regime to build a genetic laboratory in Iran (Hughes 2006:9).

Policy Implications for the United States and the Western Hemisphere

Iran’s influence in the U.S.’s backyard has sounded the alarm in Washington, D.C., among policy makers that something must be done to prevent further infiltration of the Islamic Republic in Latin America and its detrimental effects to the U.S. foreign policy in Latin America.

The U.S. government is also especially concerned about Iran’s support of terrorist organizations operating in Latin America. Hezbollah and the Sunni Muslim Palestinian group Hamas (Islamic Resistance Movement) have been actively operating in the Tri-Border Area (TBA) comprised of the cities Ciudad del Este in Paraguay, Puerto Iguazu in Argentina, and Foz do Iguaçu in Brazil. According to Joseph M. Humire, the TBA is mostly abused by criminal-terrorist franchises (Humire 2013). Blaise Misztal stated that Hezbollah’s illicit activities in the TBA involve

soliciting donations for fake charities, extorted Arab merchants in protection schemes, smuggled arms and drugs, counterfeited and laundered money, and made and sold pirated goods. These illicit activities in the TBA were estimated in 2004 to earn Hezbollah $10 million annually; by 2009 that amount had doubled to around $20 million (Misztal 2013).

The most recent government attempt to disrupt or at least put a dent in illicit criminal activities in South America involved the Royal Navy HMS Argyll. Operation Martillo was a 15-nation collaborative effort to deny transnational criminal organizations air and maritime access to the littoral regions of Central America and put a stop to the illegal movement of drugs from South America to the western world.

Another important foreign policy implication of Iran’s cozy relationship with the Bolivarian Revolution nations, which has been highly ignored by the U.S. government, is Iran’s emergence as a cyber power, which has also raised concerns among policy makers in Washington, D.C. Iran is developing its own cybersecurity capabilities with the intent to use them to launch Denial of Service (DoS) attacks, Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks, malicious code, electronic warfare, debilitation of communications, advanced exploitation techniques, and Botnets [3]. In fact, most DoS attacks are carried out by criminal elements in society, in conjunction with other transnational organized crime organizations, for the purpose of extortion. The Iranian government is investing heavily in cyber capabilities and may well turn to their proxies (the Bolivarian Revolution nations) as a force multiplier (Cilluffo 2012:22).

Despite the fact that our conversations regarding cyber-attacks or cyber-terrorism has tended to focus primarily on China and Russia, we ignore Iran at our peril. As James Clapper stated in his testimony before the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence in January 2012, “Iranian officials – including Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei – have changed their calculus and are now willing to conduct a [cyber] attack in the United States” (Clapper 2012). The Iranian government and its Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei recognize the importance of having cyber capability in addition to kinetic military capability in the wars of the twenty-first century. The Islamic Republic has suffered five external cyber-attacks (the Stuxnet, the Stars, DuQu, Wiper, and Flame) and one internal cyber-attack (Mahdi) in July 2012 (Berman 2012:13). According to Ilan Berman, Vice President of the American Foreign Policy Council, “what Iran lacks in capabilities, however, it makes up for in intent. Politically, a cyber attack from Iran is significantly more likely than from either China or Russia, in light of the ongoing international impasse over its nuclear program” (Clapper 2012:14).

Policy Options for the United States

As the United States overextends its resources in Iraq and Afghanistan while actively engaged in Syria and fighting against ISIS, U.S. foreign policy priorities will have to be established. The U.S. must pick its fights wisely if it wants to remain the “lonely superpower” in the twenty-first century.

What are the policy options for the U.S. as Iran continues to infiltrate its backyard? Are there any issues that both the U.S. and Iran can work together to create modus vivendi to start some confidence-building between the two nations? Obviously, any comprehensive U.S. response addressing Iran’s menacing acts in the Western Hemisphere must be composed of two interdependent and related prongs. One prong pertains to Latin American nations who see themselves as part of the Bolivarian Revolution movement, and hence anti-American, and willing to cultivate a self-serving relationship with Iran. This comprehensive U.S. response would also address some of the Latin American nations that share a goal of limiting Iranian influence in the Western Hemisphere. Brazil could be the pivot nation within the Western Hemisphere that could bring together other nations to create an alternative to the “axis of unity” of Iran. During Lula da Silva’s administration, Brazil had a cozy relationship with Iran and its former President Ahmadinejad. Under Dilma Roussef, relations between the two nations have suffered some strain. Roussef, Brazil’s president – herself a revolutionary activist during the Brazilian authoritarian years who was captured and tortured by the military – has been quite critical of Iran for its alleged human rights violations. Brazil, along with perhaps Colombia and Chile, could form an alternative to the “axis of unity” nations, thus bringing some stability to the region and less of an influence of Iran. This prong’s comprehensive strategy could be considered a combination of carrots to lower the anti-Americanism among the Bolivarian nations, and sticks which would impose diplomatic and economic costs for deepening ties with Iran.

The second prong requires the U.S. to work out a modus vivendi with Iran that lowers its sense of insecurity towards the U.S. The Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei believes that the U.S. government is bent on regime change in Iran, whether through internal collapse, democratic revolution, economic pressure, or military invasion (Ganji 2013:25). However, in a recent statement, the Supreme Leader stated that Iran is ready for direct negotiations with the U.S., but some preconditions must first be met. Supreme Leader Khamanei wants the U.S. to “give up what he sees as its attempts to overthrow the Islamic Republic, enter into negotiations in a spirit of mutual respect and equality, and abandon its simultaneous efforts to pressure Iran, with military threats and economic sanctions” (Ganji 2013:45). The U.S., in a gesture of good faith towards Iran, could lift the economic sanctions since “whatever their aims, sanctions inflict damage on populations at large, not only or even primarily on the governmental officials who are their ostensible targets” (Ganji 2013:47).

First, U.S-Latin American relations involve a combination of soft power and hard power. The U.S. is using its power of coercion and payment against Iran’s infiltration of Latin America (Nye 2013:9). On September 19, 2012, the House of Representatives passed H.R. 3783, otherwise known as the “Countering Iran in the Western Hemisphere Act.” The purpose of the Act is to “provide for a comprehensive strategy to counter Iran’s growing hostile presence and activity in the Western Hemisphere, and for other purposes.” The Act also authorizes the U.S. government to use a

comprehensive government-wide strategy to counter Iran’s growing hostile presence and activity in the Western Hemisphere by working together with United States allies and partners in the region to mutually deter threats to United States interests by the Government of Iran, the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the IRGC’s Qods Force, and Hezbollah.

Second, other agencies of the U.S. federal government, including the U.S. Army, can join forces to coordinate efforts to put an end to Iran’s illicit and criminal activities in Latin America. For example, on February 10, 2011, the Treasury Department identified the Lebanon-based Lebanese Canadian Bank as “a financial institution of primary money laundering concern under the PATRIOT Act (Section 311) for its role in facilitating the money laundering activities of an international narcotics trafficking and money laundering network with ties to Hezbollah.” The U.S. government, under its Nonproliferation, Anti-terrorism, Demining, and Related Programs (NADR) foreign aid funding account, is also assisting Latin American countries in their efforts to identify, arrest, and prosecute individuals engaged in criminal activities on behalf of the Islamic Republic of Iran or its proxies. Under the administration of the Department of State, the following U.S. government programs are providing much needed assistance to improve Latin American countries’ counterterrorism capabilities, and the U.S. Army could become a key player in this endeavor: Anti-Terrorism Assistance (ATA) program; an Export Control and Related Border Security (EXBS) program; a Counterterrorism Financing (CTF) program; and a Terrorist Interdiction Program (TIP).

Third, the Department of Homeland Security’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), along with the U.S. Army, can also partner with several Latin American nations and use the established Trade Transparency Units that facilitate exchanges of information in order to combat trade-based money laundering. Another important initiative by the U.S. government to combat Iran’s illicit activities and its support for transnational organized criminal organizations in Latin America was the establishment of the “3+1 regional cooperation mechanism.” This initiative was established in 2002, involving Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay – the so-called Tri-Border nations. Given the importance of both Argentina and Brazil in South America, and South America becoming a route for the transport of drugs into the U.S., the U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Army could provide Latin American nations with military training, exercises, cooperation, and exchange of technology in the fight against transnational organized criminal organizations.

Fourth, the U.S. government should consider expanding its intelligence-gathering and sharing of information with other nations in the Western Hemisphere in their fight against this global cancer called terrorism. The U.S. Army’s intelligence and counterintelligence apparatus can play an active role in assisting Latin American nations. The 9/11 attack was an attack not only against the U.S., but also an attack against all civilized nations of the international community. Blaise Misztal has recommended an expansion of the El Paso Intelligence Center (EPIC) to include other nations of the Western Hemisphere, in addition to Mexico and Colombia.

Fifth, the U.S. Government, especially its Army leadership, can also play a major role in Latin America by expanding the Mérida Initiative, an aid package program designed combat drug trafficking, gangs, and other criminal activities in Mexico in its fight against drug cartels that have wreaked havoc in the country for years and has created a massive national security concern to the U.S. along its border with Mexico (Stephens & de Arimateia da Cruz 2008). Given the Iranian connection with illicit activities in the Tri-Border region, an expansion of the Mérida Initiative would provide South American nations with much needed funds to address the drug war in the Americas and its potential spill-over into the U.S. territory. An expansion of the Mérida Initiative to include other nations of Latin America would allow the U.S. Army’s counterinsurgency expertise and techniques in its fight against transnational organized criminal organizations.

Finally, with the election of Hassan Rouhani as president of the Republic of Iran and the change in discourse by Iran’s Supreme Leader Khamenei, the U.S. could take this opportunity to pursue a policy of rapprochement towards Iran. The U.S. could consider an old Cold War strategy in its relationship with Iran: the establishment of a Tehran-Washington hotline. The hotline approach would be similar to the one set up in the aftermath of the Cuban missile crisis between Washington-Moscow, or between Washington-Beijing in 1998 (Goldstein 2013:141). This direct hotline will show Tehran that the U.S. is serious about their relationship and also recognizes the importance of direct communications between their top leaders without interlocutors.

Conclusion

Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in May 2009 stated that the United States was disturbed by Iran’s “gains” in Latin America (Karmon 2010: 16). Indeed, Iran’s penetration of Latin America in such a short period of two to three years presents a serious concern to the U.S.’s national security interests in the Western Hemisphere.

U.S. foreign policy response toward Iran could continue to treat Iran as a “villain” or “engage the enemy.” According to Paul R. Pillar, “American needs a foreign villain” and “well-suited on several counts to play the current role of villain is that other state on the Persian Gulf with oil resources and radical politics: Iran” (2013:218). Or, the U.S. could “engage the enemy” in a constructive dialogue that could result in enormous dividends to the U.S. and stability in the Persian Gulf. The U.S. National Security Strategy calls for expanding U.S. engagement with “other key centers of influence.” With the recent election of Hassan Rouhani as president of the Islamic Republic of Iran, there is a window of opportunity for the U.S. to attempt to the bring Iran to the diplomatic table. President Rouhani has stated that he intends to pursue constructive relations with the international community, improve Iran’s economy, and resolve the nuclear issue. Perhaps now more than ever, U.S. policy makers should follow the advice of Steven E. Lobell: be aware that threats or policies of punishment might allow hard-line nationalists to seize on these threats as an opportunity to weaken and stifle the reformers (2013:287).

Notes

NB: All views are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

[1] The reference to Latin America as the U.S. backyard dates back to December 2, 1823 when President James Monroe established the Monroe Doctrine. The Monroe Doctrine established that the Western Hemisphere as the U.S. backyard and any intervention by European colonial superpowers would be considered an attack of aggression and a declaration of war and the U.S. would defend its neighbors and the hemisphere from such an attack.

[2] Joseph E. Stiglitz in his book Globalization and Its Discontents (2002) defines the Washington Consensus as “a consensus between the IMF, the World Bank, and the U.S. Treasure about the right policies for developing countries—a signaled radically different approach to economic development and stabilization” (pg. 16). Joseph E. Stiglitz, Globalization and Its Discontents. New York: W. W. Norton, 2002.

[3] For an in-depth discussion of each of the mentioned techniques of information warfare read Seymour Bosworth, M.E. Kabay, and Erich Whyne Computer Security Handbook 5th edition Volumes 1 & 2. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

References

Arnson, Cynthia, Haleh Esfandiari, and Adam Stubits, “Iran in Latin America: Threat or Axis of Annoyance?,” Woodrow Wilson International Center Reports on the Americas, #23.

Berman, Ilan. “Iran Courts Latin America,” Middle East Quarterly, Summer 2012, Vo. 19 Issue 3.

Berman, Ilan, “Cyberwar and Iranian Strategy,” American Foreign Policy Council, Defense Dossier Issue 4 August 2012.

Berman, Ilan. “Threat to the Homeland: Iran’s Extending Influence in the Western Hemisphere,” Testimony before the House of Representative Homeland Security Committee Subcommittee on Oversight and Management Efficiency, July 9, 2013.

Bosworth, Seymour, M.E. Kabay, and Erich Whyne Computer Security Handbook 5th edition Volumes 1 & 2. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Brun, Elodie, “Iran’s Place in Venezuela Foreign Policy, “ in Iran in Latin America: Threat or Axis of Annoyance? Woodrow Wilson Center Reports on the Americas, No. 23, pg. 15.

Cilluffo, Frank J., “The U.S. Response to Cybersecurity Threats,” American Foreign Policy Council, Defense Dossier Issue 4 August 2012.

Clapper, James, Testimony before the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, January 31, 2012.

Corrales, Javier and Michael Penfold, Dragon in the Tropics: Hugo Chavez and the Political Economy of Revolution in Venezuela, Brookings Institute Press, Washington, D.C. 2011.

Department of Defense, Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Executive Summary: Annual Report on Military Power in Iran,” April 2012.

Farhi, Farideh. “Tehran’s Perspective on Iran-Latin America Relations,” in Iran in Latin America: Threat or Axis of Annoyance? Woodrow Wilson Center Reports on the Americas, No. 23, pgs.29-30.

Ganji, Akbar, “Who is Ali Khamenei? The Worldview of Iran’s Supreme Leader,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2013.

Giacalone ,Rita. “Venezuelan Foreign Policy: Petro-Politics and Paradigm Change,” in Ryan K. Beasley, Juliet Kaarbo, Jeffrey S. Lantis, and Michael T. Snarr Foreign Policy in Comparative Perspective: Domestic and International Influences on State Behavior 2nd edition. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 2013.

Goldstein, Avery, “China’s Real and Present Danger: Now Is the Time for Washington to Worry,” Foreign Affairs September/October 2013: 136-144.

“HMS Argyll completes intense period of counter-narcotics operations in eastern Pacific,” Friday, August 30, 2013.

H.R. 3783, “Countering Iran in the Western Hemisphere Act.”

Hughes, John “Latin America’s leftists regimes get cozy with Iran,” Christian Science Monitor, 2/15/2006, Vol. 98, Issue 56.

Humire, Joseph M., “Threat to the Homeland: Iran’s Extending Influence in the Western Hemisphere,” Testimony to the U.S. House of Representative, July 9, 2013.

“Iran after closer relations with Latinamerica, says new president Rouhani, August 5th, 2012.

Karmon, Ely, “Iran Challenges the United States in Its Backyard, in Latin America,” American Foreign Policy Interests, 32: 276-296, 2010.

Katzman, Kenneth. “Iran: U.S. Concerns and Policy Responses” (CRS Report No. RL32048) Retrieved from Congressional Research Service.

Lobell, Steven E., “Engaging the Enemy and the Lessons for the Obama Administration,” Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 128, No. 2 (Summer 2013): 261-287.

Misztal, Blaise, “Threat to the Homeland: Iran’s Extending Influence in the Western Hemisphere,” Committee on Homeland Security, U.S. House of Representatives, July 9th, 2013.

Noreiga, Roger F. “Hugo Chavez’s Criminal Nuclear Network: A Grave and Growing Threat”.

Nye ,Joseph S., Presidential Leadership and the Creation of the American Era. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2013.

Pillar, Paul R., “The Role of Villain: Iran and U.S. Foreign Policy,” Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 128, No. 2 (Summer 2013): 211-231.

Stephens , Laura K. and José de Arimateia da Cruz, “The Mérida Initiative: Bilateral Cooperation or U.S. National Security Hegemony, International Journal of Restorative Justice, 2008, vol. 4, no. 2.

Stiglitz, Joseph E. Globalization and Its Discontents. New York: W. W. Norton, 2002.

Sullivan, Mark P, “Latin America: Terrorism Issues,” (CRS Report No. 21049)Retrieved from Federation of American Scientist.

Supreme Leader’s Inaugural Speech at the 16th Non-Aligned Summit, August 30th, 2012.

Wiarda, Howard J. (2011). American Foreign Policy in Regions of Conflict: A Global Perspective. New York: NY, Palgrave Macmillan.

Wiarda, Howard J. (2012). American Foreign Policy in Regions of Conflict: A Global Perspective, New York: NY, Palgrave Macmillan.

Figure 1: Structure of the Iranian Government

Source: Kenneth Katzman, “Iran: U.S. Concerns and Policy Responses” (CRS Report No. RL32048) Retrieved from Congressional Research Service.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Significance of the Iran Hostage Crisis for International Dispute Settlement

- National Honor and Religious Duty: Iran’s Strategic Evolution in Confronting Israel

- Opinion – China’s Saudi-Iran Deal and Omens for US Regional Influence

- Opinion – The Mearsheimer Logic Underlying Trump’s National Security Strategy

- The US-Iran-China Nexus: Towards a New Strategic Alignment

- US Bombing of Iran and the Transition to a New International Legal Order