Post-Communist Transitions and MIDs: How China, Laos, and Vietnam Foreshadow International Peace after North Korea’s Post-Communist Transition

This essay uses past cases of post-communist transitions to better understand the future of North Korea, one of the few remaining communist states existing today. By measuring and comparing the number of military interstate disputes (MIDs) that involved China, Laos, and Vietnam during the period before and after those countries’ political-economic transitions, this research investigates the relationship between international security and economic reform. The MID dataset employed in this research was compiled by the Correlates of War Project to record information about conflicts that “range in intensity from threats to use force to actual combat short of war.”[1]

On December 19, 2011 the world heard news of the death of Kim Jung-il, the “supreme leader” of North Korea, who was to be succeeded by his son, Kim Jung-un. On April 21, 2012, the then 29 year-old Kim Jung-un delivered his first official speech in front of 70,000 North Koreans gathered in the Kim Il-sung Stadium.[2] In his speech, Kim emphasized that economic reform will lead to a more prosperous country and better lives for North Koreans, insisting that he will ensure his people would “never have to tighten their belts again.”[3]

There have been reports of economic liberalization, particularly after Kim Jong-un assumed the leadership in 2012. The sudden dismissal of Ri Young-ho who was formerly a prominent and conservative North Korean military officer, the unprecedented public appearance of the North Korean first lady, and the appearance of Disney characters on stage of North Korean performances seemed to point to some sort of transition towards a more open society. However, despite endeavors towards decentralization, Pyongyang’s adherence to rigid communism continues as of 2014. It is hard to say North Korea will change any time soon. However, hints from trade data, news reports, and testimonies of North Korean refugees indicate that change is in progress, although very slowly.

At the Kaesong Industrial Complex, located a few miles north of the heavily armed inter-Korean border, around 50,000 North Koreans are working for small South Korean manufacturers. This place, called “a rare state-sanctioned capitalist enterprise in the North,” was closed for five months in 2013 during escalating tensions on the peninsula. [4] But by September, 2013, the complex reopened and output has almost fully recovered since then. After its revival, North Korea has made announcements about developing new special economic zones across the country that can attract foreign investment and increase overseas trade. Around the same time, Yonhap News Agency of South Korea reported news on North Korea’s new law that calls for building special economic zones. Based on this law, North Korea announced that it will be building a new “high-tech” industrial park near the Kaesong complex. Under the law, the special zones would give “preferential treatment” to foreign businesses.[5] On June 6, 2014, the same sources reported that the northeastern Chinese city of Dandong announced plans to develop tours of an economic zone on a North Korean island on the border with China.[6]

Despite long endeavors, North Korea is still one of the poorest countries in the world with its economy at the brink of collapse.

“In the last decades of the 20th century, North Korea’s economy went from bad to worse, hitting rock bottom during the famines of the 1990s. To survive, North Koreans began to engage in private market activity, which today accounts for as much as 80 percent of family income,”

wrote Park Yeon-mi in her article, The hopes of North Korea’s ‘Black Market Generation’ published in the Washington Post on May 26. Park is a media fellow at Freedom Factory, a for-profit think tank in Seoul who escaped North Korea in 2007. In her article, Park claims that her generation, often quoted the Jangmadang or “Black Market Generation,” will make “permanent changes” in the future of North Korea towards a freer nation.[7]

Likewise, evidence coming from various sources point North Korea to a state that involves some sort of transition to a more open and efficient society the country may be or is already undergoing. Such signs of transition are more eminent in the economic sector with numerous surveys and statistical evidence that indicate change in the North Korean economy to what is called “post-communist.” Post-communist is a term describing the period of political and economic transformation or transition in former communist states located in parts of Europe and Asia, in which new governments aimed to create free market-oriented capitalist economies.

North Korea’s potential to undergo post-communist transition has many important implications. However, this paper will mainly focus on its effects on international security. The motivating question for the sections that follow is: “does the political-economic transition of a communist country enhance international security, or undermine it?”

Literature Review

Many scholars have projected different opinions on the relationship between international trade and world peace. Ketherine Barbieri categorized four types of propositions that have evaluated the trade-conflict relationship in different ways. The first is the liberal theory: trade promotes peace. The second argument was advanced by neo-Marxists who insisted “symmetrical ties may promote peace while asymmetrical trade leads to conflict.” The third proposition suggests that trade in fact, leads to more conflict. Finally, the forth asserts that any type of economic trade is irrelevant to conflict.[8]

For many liberal theorists, the spread of economic liberalization has represented a conduit toward peace and prosperity among nations. Richard Rosecrance and Edward Mansfield maintain that the “expansion of trade over time has resulted in a general reduction of intensive forms of interstate conflict.”[9] Both scholars’ research mainly focuses on the link between economics and international relations; largely relying on the theory of “commercial liberalization,” positioning that promotion of free trade is the road to peace.

In his book, the Rise of the Trading State: Commerce and Conquest in the Modern World, Rosecrance states that after World War II, a “trading system” began to evolve, substituting the former “territorial system.” He adds that in such a world, “large-scale territorial expansion began to evolve as too costly.”[10] In other words, conflict is limited by economic trade because there is no longer incentive to wage a war that will disrupt beneficial interdependence. Mansfield shares similar views with Rosecrance. He insists in his book, Power, Trade, and War that “continued expansion of international trade offers an avenue for improving political relations while, at the same time, increasing global welfare.”[11]

On the other hand, scholars and researchers who believe that trade will actually increase international conflicts are a group of theorists who insist that expanded global trade accompanies conflict. Benjamin Cohen is one of them; according to his book, the History of Colonialism and Imperialism, “military force may be used in conjunction with trading strategies to establish and maintain inequitable economic relationships.”[12] In the meantime, others who believe that the trade-conflict relationship is nonexistent in the first place are usually realist theorists. These analysts insist that trade has less influence in determining the incidence of international conflict than military considerations.[13]

This paper presents an argument in line with liberal theorists who insist that the expansion of free economies and economic interdependence leads to more peaceful international relationships. In order to test this hypothesis, we examine case studies of China, Laos and Vietnam; all of which are countries that had once maintained strict planned economies such as North Korea but have undergone economic reforms that increased the rate of their international trade and investment. We also put into consideration that all three countries mentioned above are located in the Asian region and that they share similar historical, social, and cultural, elements. This is to make it easier and more reliable to make connections between our findings with the future of North Korea. Thus, we will ultimately provide substantial statistical evidence from existing cases that will suggest that North Korea’s post-communist transition will contribute positively to international security.

In order to evaluate the degree of international peace or security, we will use the most recent version of MID data. As of 2014, the latest dataset is version 4 compiled by the Correlates of War Project. It provides records of every threat, display, or use of force between or among members of the interstate system between 1816 and 2010.

While North Korea remains a threat to the international society, it is currently showing signs of change – be it gradual or dramatic – unlike any other time in its history. Thus, we will ultimately provide statistical evidence that will give an outlook on how neighboring countries and international society may have to deal with North Korean issues after the country’s possible post-communist transition.

Primer to MIDs (Militarized Interstate Disputes)

The MID data (version 4.01) shows the number, type and level of interstate disputes from the year 1816 to the end of 2010. The data is categorized by the date and year the dispute occurred. In order to analyze the MID data for a certain country, you must skim through the document looking for the code number for that country and collect the data one by one. The code numbers for China, Laos and Vietnam were 701, 812, and 816.

This paper will also utilize the MID data to gain information on the fatality level as well as the hostility level of the disputes that occurred in the three countries. Fatality level is marked by numbers from 0 to 6. Hostility level is indicated by numbers from 1 to 5.[14]

| Fatality level of dispute: | Hostility level of dispute | ||

| Level # | Level of Dispute | Level # | Level of Dispute |

| 0 | None | 1 | No militarized action |

| 1 | 1-25 deaths | 2 | Threat to use force |

| 2 | 26-100 deaths | 3 | Display of force |

| 3 | 101-250 deaths | 4 | Use of force |

| 4 | 251-500 deaths | 5 | War |

| 5 | 501-999 deaths | ||

| 6 | > 999 deaths | ||

| – 9 | Missing | ||

| Table of Action Codes with Hostility Levels | |||

| # | Code Action [Hostility level] | 13 | Fortify border [3] |

| 1 | No militarized action [1] | 14 | Border violation [3] |

| 2 | Threat to use force [2] | 15 | Blockade [4] |

| 3 | Threat to blockade [2] | 16 | Occupation of territory [4] |

| 4 | Threat to occupy territory [2] | 17 | Seizure [4] |

| 5 | Threat to declare war [2] | 18 | Clash [4] |

| 6 | Threat to use nuclear weapons [2] | 19 | Raid [4] |

| 7 | Show of troops [3] | 20 | Declaration of war [4] |

| 8 | Show of ships [3] | 21 | Use of CBR weapons [4] |

| 9 | Show of planes [3] | 22 | Interstate war [5] |

| 10 | Alert [3] | 23 | Joins interstate war [5] |

| 11 | Nuclear alert [3] | – 9 | Missing [-9] |

| 12 | Mobilization [3] | ||

China’s Post-Communist Transition—Reform and Opening Up

China is the world’s second largest economy with a vast population of over 1.3 billion. With vast landscape, population and abundant resources, the ancient Chinese civilization flourished and the country continuously conquered several states to expand its empire until the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911. Ruled by the Republic of China, China acquired Taiwan from Japan during World War II. A series of the Chinese Civil War took place from 1946 to 1949 and the Chinese Communist Party finally seized control over mainland China, defeating the nationalist Kuomintang. People’s Republic of China (PRC) in Beijing was established on October 1, 1949.

Until 1978, PRC adhered to a Soviet-style centrally planned economy which led to stagnated economic growth over the next decades. Compared to other neighboring East Asian countries like South Korea, Japan and even Taiwan, China’s economic development progress was stalled despite its advantageous economic background. Prior to the PRC government, China’s economic development was disrupted by the war against Japan and a series of local Civil Wars. Subsequent Cultural Revolution and unfavorable policies like the Great Leap Forward causing famine, further hampered economic development of the nation. Acknowledging the inefficiency of a planned economy system, Deng Xiaoping initiated the post-communist transition in the economic sector in the name of Chinese economic reform, literally meaning “reform and opening up”.[15]

China’s initial economic reform included agricultural reform, privatization of business, opening up towards foreign investment. The degree of privatization and exposure to market competition gradually increased. In the 1990s, China intensely engaged in international trade. Joining the World Trade Organization in 2001, the government proposed various trade policies with less trade barriers and regulations. Tariffs on imports were also reduced and international exchange with rest of the world increased with the volume of international trade. The introduction of capitalist market mechanisms with expansion of international trade tremendously boosted China’s economic growth and national wealth.

Post-communist transition in the economy has not only improved China’s economic growth, but also the nation’s status in international relations. With the second largest GDP in the world, China has become one of the most influential nations in the world economy. It is true that there are voices of concern about China’s growing economic power, which may be used as political leverage over rest of the world.[16] However, engagement in international transaction has also reminded China of international responsibilities of a major player as well. Variations in MIDs (Militarized Interstate Disputes) can effectively show how China has been decreasing its aggressiveness in dealing with various interstate disputes.

Analysis of China’s MIDs Before and After the Post-Communist Transition

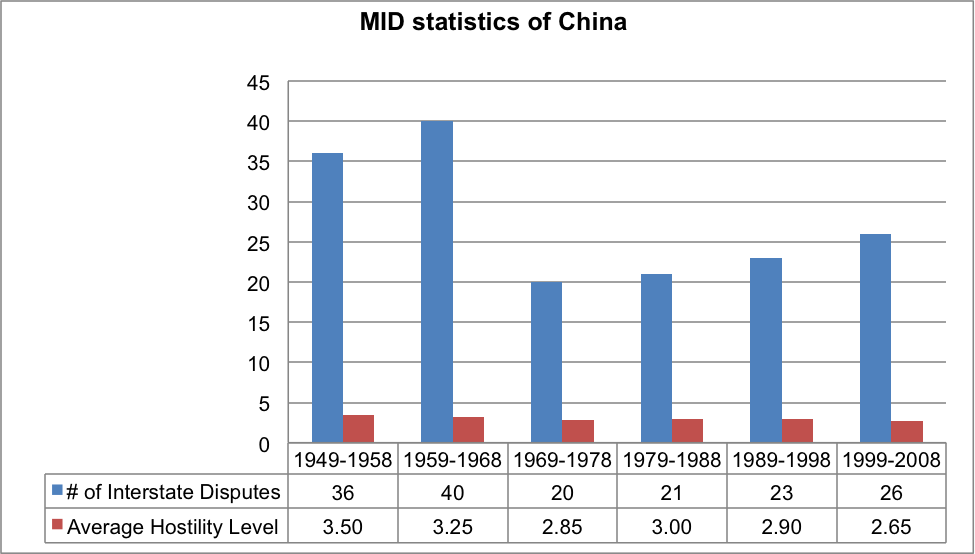

By studying the number of MIDs and the hostility level of China’s responses in each interstate dispute, it can be determined whether post-communist transition in China’s economy has positively affected international security and peace.

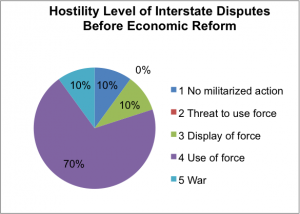

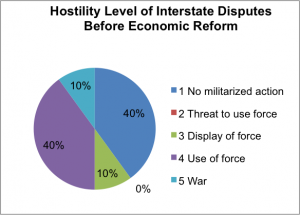

Since 1978 when China initiated its economic reform, it is clearly shown that hostility level of China’s reaction to interstate disputes decreased. While interstate disputes with hostility levels 4 and 5 comprised more than half of total interstate disputes before the post-communist transition, interstate disputes with hostility levels of 4 and 5 decreased 29 percent after the transition. Most interstate disputes stopped before the usage of any force during this period. The number of interstate disputes halved from 40 to 20 during the last 10 years of China’s Soviet-style rule. Once after economic reformation was officially initiated, the number of disputes remained below 30 for every decade in comparison to the decades before the reformation when for every ten years, more than 30 interstate disputes took place. Although the number of disputes shows gradual increase as it comes to more recent years, hostility levels have clearly decreased.

Apparent changes in the hostility level of interstate disputes could also be observed from following figures. Before post-communist transition, China aggressively joined interstate war as it continued the acquisition of other states to expand its empire in Qing Dynasty. Interstate disputes with the hostility level over 4 include the Korean War in 1950 and the Sino-Indian War in 1961. Out of 96 interstate disputes between 1949 and 1978, 60 were of hostility level 4 and 5. China directly used its military force or even raised a large scale war often when faced with territorial or political disputes.

More than 70% of the disputes that took place before 1978 involved an action code over 10, which means “Alert.” Although China had territorial disputes with the Philippines and Vietnam even after 1978, the number of interstate disputes that involved an action code over 10 reduced to half of the total number after its transition. Not only has the number of territorial disputes, but also China’s degree of militarized reaction towards other nations decreased. Except for political disputes with Taiwan and confrontation with Russian fishermen over fishing on the border between Siberia and Manchuria, China has not shown outstanding aggressiveness or militarized action in interstate disputes. Especially after the 1990s, when China has actively engaged in international trade and transactions, it is hard to find interstate disputes that contain militarized action.

In the case of China, as the nation became more engaged in market economy and international trade after post-communist transition, less aggressiveness or militarized action in interstate disputes were observed from the MID data. Apart from political regime or national characteristics, economic prosperity by more openness to international market and trade may be a positive factor that contributes to more stable international security and peace.

Laos’s Post-Communist Transition—Reform and Opening Up

Laos is a small mountainous country surrounded by Vietnam, China, Thailand, Myanmar, and China. Although it is a small country, the process of post-communist transition that it went through should not be overlooked. After becoming an independent country in 1953, the policies and market were controlled under the socialist government system until 1985. Economic management was weak due to the lack of skilled labor. Although there was some external assistance, many projects were not completed at a satisfactory level.[17]

It was in 1986, which was 11 years after independence, that Laos started making movements for reformation in the market. It acknowledged the need for a new economic system to boost the economic development of the nation. Under the NEM (Newly Market Mechanisms), Laos sought changes to convert the economy to a market-oriented system from a centrally planned economy.

The main reason for economic development was to improve the overall conditions of the nation, including factors such as welfare, transportation, income gap reduction, and global market entrance. Laos has pursued significant economic and institutional reforms aimed at improving the social and economic well-being of its population by consistently building a market-orientated economy.[18] Despite many obstacles, Laos has managed to achieve beneficial results from economic reform.

When analyzing and evaluating the post-communist transition of a nation, many statistics and domestic reviews should be studied in various sectors. Both foreign and domestic investment increased and an advanced transportation system between regions was constructed. Trading of products that were limited became possible and easier for the mountainous lands of Laos.

Analysis of Laos’s MIDs Before and After the Post-Communist Transition

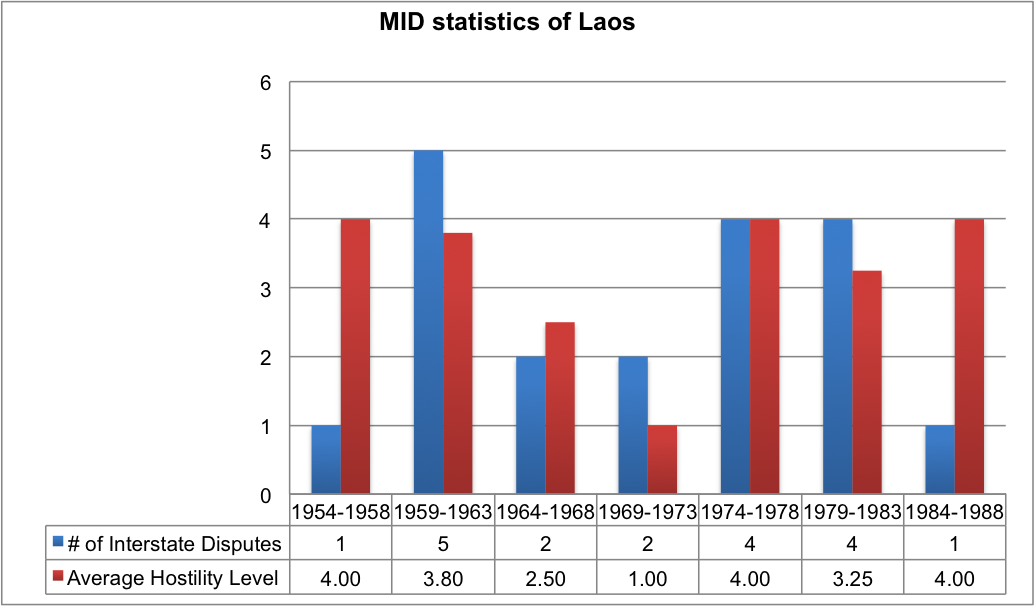

Before the years of post-communist transition in 1986, there was serious instability in the country’s grounds. Out of 18 interstate disputes that occurred before the country’s transition, 13 were hostility level 4, which stands for “use of force.”

Starting from 1960, Laos was literally a battlefield for wars that occurred during the time. Although Laos was not directly involved in the war between North and South Vietnam, the Vietnam War was a tragic development for Laos. Amid the tragedy, there was another war that strongly influenced the stability of Laos. Just as the Vietnam War started, another war began. However, this war was shadowed by the Vietnam War and later earned the name, Secret War. The countries involved in the Secret War were the U.S., Thailand, Laos, and North Vietnam.[19]

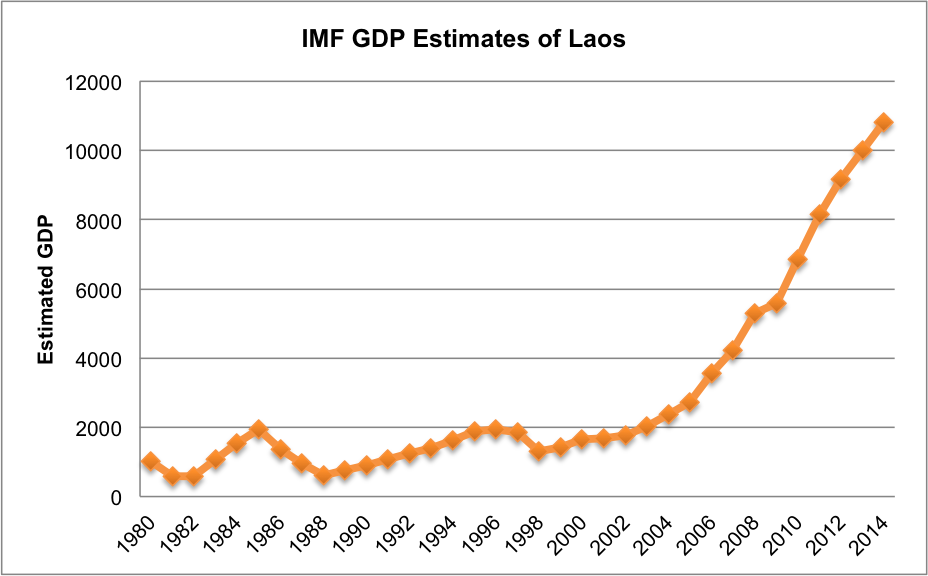

Unfortunately, the MID data of Laos stops after 1988. Therefore, the results of the country’s post-communist transition were evaluated through domestic disputes, the changes in GDP (Gross Domestic Product) announced by the IMF, and through the overall economic international cooperation efforts of Laos after the transition period.Unlike the name, the number of estimated deaths was too much to be kept a secret. From 1964 to 1973, the U.S. dropped more than two million tons of ordnance on Laos throughout 580,000 bombing missions, making Laos the most heavily bombed country per capita in history.[20] The bombings were part of the U.S. Secret War in Laos to support the Royal Lao Government against the Pathet Lao and to interdict traffic along the Ho Chi Minh Trail.[21] Therefore, due to the uncountable bomb deaths, the fatality rate on the MID chart appears as -9, meaning “unknown.” This all happened before the post-communist transition of Laos.

Unfortunately, the MID data of Laos stops after 1988. Therefore, the results of the country’s post-communist transition were evaluated through domestic disputes, the changes in GDP (Gross Domestic Product) announced by the IMF, and through the overall economic international cooperation efforts of Laos after the transition period.Unlike the name, the number of estimated deaths was too much to be kept a secret. From 1964 to 1973, the U.S. dropped more than two million tons of ordnance on Laos throughout 580,000 bombing missions, making Laos the most heavily bombed country per capita in history.[20] The bombings were part of the U.S. Secret War in Laos to support the Royal Lao Government against the Pathet Lao and to interdict traffic along the Ho Chi Minh Trail.[21] Therefore, due to the uncountable bomb deaths, the fatality rate on the MID chart appears as -9, meaning “unknown.” This all happened before the post-communist transition of Laos.

Just a few years before the year Laos began its post-communist transition, the number of such deadly disputes peaked. Between 1974 and 1983, eight interstate disputes occurred, all of which were marked -9 in fatality rates. In other words, four fatal disputes took place every two years just before the post-communist transition of Laos. This rate drops to just one – the Thai-Laotian Border War of 1987 – after the transition. The Thai-Laotian Border War ended shortly after one year of its initiation. Likewise, the reduced number of confrontations right after the transition implies that Laos’ shift towards a more open economy had a positive effect on international security.

There are some negative aspects of the post-communist transition of Laos internally. This is mainly due to the fact that the military acted as a powerful leader in the process. The process was accelerated more by pressure rather than independent planning and acting. The collapse of the communist regimes in Central and Eastern Europe and the end of their financial assistance accelerated the reform process in Laos during the first half of the 1990s.[22] The need to find alternative sources of assistance, combined with the ideological vacuum following the collapse of communism, obligated the Lao leadership to accept the kind of market-oriented reforms advocated by the donor community, especially the IMF and the World Bank.[23] With the military in the lead, disputes within the nation were inevitable. The Hmong groups demonstrated and rebelled against the communist government severely. In the late 1990s, several ambushes were launched by the Hmong rebellion along the road between Vientiane and Luang Phrabang.[24] Even in the new millennium attacks continued. In 2003, 10 people were killed in an ambush and among the 10 people, tourists were included. This called for an intervention of the Vietnamese troops.

Yet, because of post-communist transition, the military disputes with other states that Laos struggled from in the 1900s began to break down starting from the late 1900s. Although the political system remained to be under the control of the military leadership, the plan to convert to a market-oriented economy visualized a new image of Laos to other countries. In the early 1990s Laos rapidly went through the process of post-communist transition. Despite the reduction in donations due to the communist government, Laos acted fast to boost the economy and develop international cooperation. Efforts have continued throughout the years and many projects were kicked off. Since the early 2000s, the Lao government has made some efforts to regain some credibility among the international donors. One example of this is the drafting of a National Poverty Eradication Programme (NPEP) which is expected to receive the support of the donor community and give it the impression that the Lao government is a reliable partner.[25]

The post-communist transition of Laos may have provoked some disputes within the regions of the nation due to the militarization of the political intellectuals. However, by focusing mainly on the relationship between the economy and the outward military disputes with other nations, it can be studied that the market-oriented economy of Laos has actually allowed the country to cooperate with the global economy and ease the governmental tension to a less dangerous level. The economy has gained noticeable stability and the market prices have not fluctuated much since the post-communist transition. According to the graph below provided by the United Nations’ National Acocounts Database and International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook (WEO) Database, April 2014 edition, the GDP of Laos has skyrocketed during the years of post-communist transition.

After the years of transition, the GDP rate has remained relatively constant without extreme falls or increases. After long years of negotiation, Laos is finally getting ready to join the WTO (World Trade Organization) with an approval that took more than 10 years. Laos has been making many efforts of its own to fulfill the requirements and qualifications. Import tariffs were reduced and will open some of the service sectors of the national economy and join foreign competition.

WTO membership should encourage greater foreign investment, and should help Laos sustain its impressive growth rates of recent years, running between 6% and 8%. The opening of Laos and deeper entrance into the foreign market may help reduce the communist power within the region and the rebels against the powers. The WTO has put this into consideration and is striving to come up with plans to avoid Laos from becoming a case like China and Vietnam, which are one-party communist states that are going through similar internal conditions as Laos. As Laos sought to improve international cooperation through post-communist transition, this may be a chance to get one step closer to its goal.

Vietnam’s Post-Communist Transition—Doi Moi

Since its reunification in 1976, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (Vietnam) imposed central planning economy with the launching of the 1976-80 Five Year Plan.[26] The Five Year Plan opted for the Soviet-style central planning, focused on the heavy industry and development of agriculture. However, the plan turned out to be a failure, unable to stabilize the economy through the bad harvest caused by the bad weather. Although the price level was controlled by the government, the annual inflation rate escalated to 700 percent; budgets were not evenly distributed as military expenditure and unsuccessful state-owned enterprises required more and more capital. As the neighboring countries boasted their economic development, Vietnam’s high officials perceived the need of economic transition in order for a major renovation.

Doi Moi, or Policy of Renewal, was implemented at the Sixth Party Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam in December 1986. It was aimed for the transition from the socialists’ approach of centrally-planned economy to a market economy, reducing macroeconomic instability, accelerating economic growth and generating incentives for people to work harder and efficiently.[27] Resources were to be allocated to the three main objectives, which were the development of agriculture, the expansion of consumer goods production and the expansion of trade and foreign investment relations.[28]

In accordance of Doi Moi, the Vietnamese government managed to reform structural problems within its economy. Land owned by the agricultural cooperatives was returned to the farming households. The government-controlled prices for the commodities were liberalized, which stabilized the commercial economy. Budget deficits decreased as the resource allocation towards state-owned enterprises was reduced and the tax system was restructured. As well as promoting private enterprises to operate with more freedom, investment and trade were also liberalized.

As a result of the extensive economic transition to the market-oriented economy, the Vietnamese economy was revived. Vietnam’s GDP increased approximately eight percent per a year as inflation and real interest rates became stable. In the longer perspective, these reforms enabled the country to enjoy rapid economic growth until the Asian economic crisis of 1997 and 1998.

Analyzing Vietnam’s MIDs: before and after Doi Moi

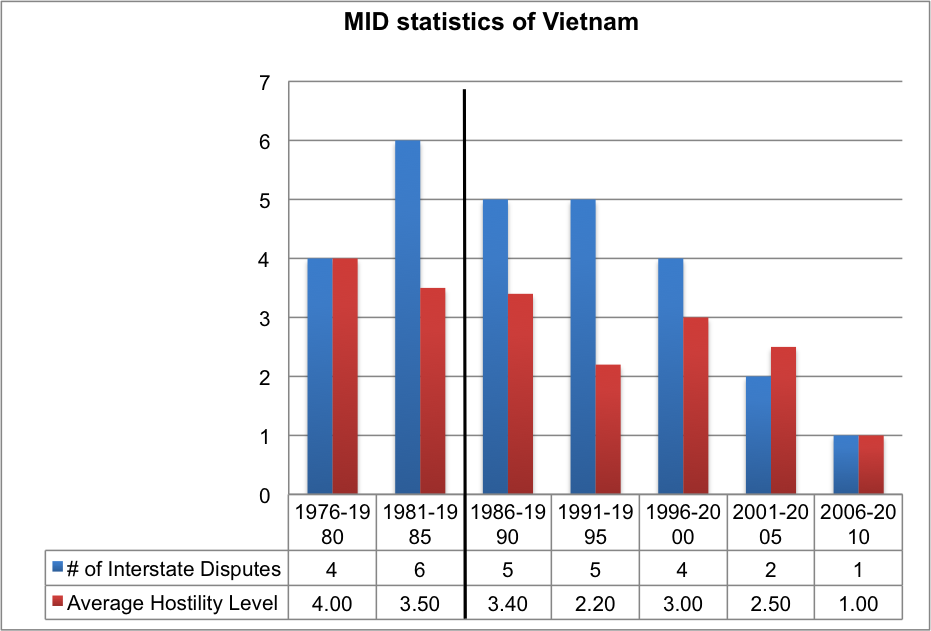

MID data clearly shows Vietnam’s post-Communist transition into a market-oriented economy has helped enhance international security. The data below shows the aggregated number of Vietnam’s MIDs, comparing periods of five years throughout 1976 to 2010. The Doi Moi took place in 1986. It is hard to determine the direct effect of the economic reform, as the number of disputes for every five years had stayed quite the same right after Doi Moi. However, the number of interstate disputes clearly goes down with the pass of years. By the 2000s, the number of disputes goes down to just one or two in five years.

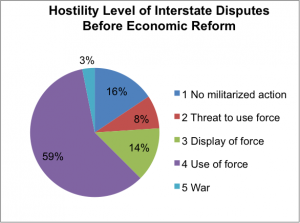

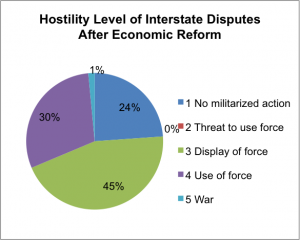

There were also some clear changes in hostility levels before and after the economic liberalization. Below, two charts indicate hostility levels of each MID. While the first chart focuses on disputes that occurred during the last 10 years before Doi Moi, the chart underneath focuses on the disputes that took place during the 10 years after Doi Moi.

Seven out of ten interstate disputes in Vietnam, which accounts for about 70 percent of the total disputes that occurred in the decade before economic reformation were above level 4, which stands for “use of force.” One interstate dispute was recorded as level 5, which stands for “war.” This confrontation is the Vietnam War of 1975 which killed more than an estimated number of 3.1 million civilians and soldiers.

On the other hand, it is noticeable that in the following decade, after the post-Communist transition and economic reform of Vietnam, the level of hostility gradually goes down. Compared to the former decade which only had one dispute out of ten with the level 1 in hostility, close to half of all the disputes that occurred during the latter decade was involved no militarized action. Interstate disputes with the level 4 in hostility reduced to just 40 percent during this period.

Although the absolute number of interstate disputes had not decreased after Doi Moi, the second decade allowed Vietnam to encounter a more stable international security environment, proved by the overall lower level of MID hostility compared to the first decade.

Sino-Vietnamese Conflicts of 1979-1990, Normalization and Decreased MIDs

Out of 20 MIDs between years 1977 to 1996, Vietnam faced 10 disputes with the People’s Republic of China, which accounts for 50 percent of the total MIDs. This is caused by the effects of the Sino-Vietnamese conflicts, lingering even after the post-communist transition of Doi Moi. The series of border disputes that started from the end of the Sino-Vietnamese War in 1979 led to the Chinese troops occupying Vietnam’s territory along the border. As the land possessed important value in its history, Vietnam started to engage in fights in order to regain control of the area.[29] As China gradually withdrew its occupation of Vietnamese territory, Vietnam and China normalized their relations in 1991.

Eventually, this diplomatic breakthrough turned out to form a positive environment for Vietnam in constructing mutually beneficial economic relations with China, which led to a decreased number of disputes between the two countries. Freed from China’s military threat, Vietnam was able to spend substantially less on military expenditures, which, for decades, had been escalating into a major component of its budget deficits, and focus on economic recovery. Both countries resumed bilateral trade and investments; since then, these two countries have seen stable and rapid growth, where annual trade increased from $32 million in 1991 to $2.5 billion in 2000.[30]

The effect of the liberalized economic relations can also be seen in the decreased MIDs in Vietnam within a decade since the normalization. Out of 9 interstate disputes, China was involved in 4 with Vietnam, which accounts for 45 percent. To compare the identical statistics with a decade before the normalization, there were 12 disputes in total, where China took part in 8, accounting for 67 percent of the whole MIDs in that period. In addition, the average hostility level of MIDs in Vietnam in years between 1991 and 2001 decreased to 2.5, whereas the same indicator was measured as 3.6 in years between 1980 and1990.

Conclusion

Overall, through analyzing MID statistics of China, Laos and Vietnam before and after these post-communist transitions, moving from a planned economy towards a more market-oriented economy increased free trade with other countries and helped create a more stable and beneficial international environment. However, each country had its particular characteristics that differentiated its economic transition.

China had been a great empire in East Asia region, and it has become one of the greatest economic powers in the world today. Because of its military capacity, vast land and population, China had been always considered as an international threat as it continuously joined a series of interstate wars to conquer other states to strengthen its empire. However, since China initiated post-communist transition in 1978 towards open market economy with more intense international trade, China has apparently shown much less aggressiveness in dealing with interstate disputes, as shown by lower hostility level of MIDs after economic reform. In case of China, the nation could enjoy considerable benefits and opportunities from international trade and cooperation because of its economic scale and significance in the natural resources or labor market. In return, China seems to cope with overall international expectation or obligation as its influence and participation in the world economy increases, and China’s post-communist transition eventually contributed to international security by making China more predictable.

Laos is a country that relates to the Korean proverb, “A small pepper is spicier.” While it was literally stuck between the surrounding countries during the Vietnam War and Secret War, it managed to maintain its status and achieve desired changes in its economy. If it had not gone through post-communist transition, the position of Laos in the international community may have been a notably worse. Since neighboring countries have made economic transitions, Laos would have faced isolation. This could have caused antagonism within Laos toward other countries. However, leaders were wise enough to acknowledge the need to open up the market and transition to a market-oriented economy. Due to the transition Laos was able to cooperate with the international community more intimately in economic terms and calculate positive GDPs. Unlike Vietnam and China, there were no MID statistics recorded after the post-communist transition of Laos. Although there may have been minimal disputes with other states, Laos has actually achieved one of its goals through transition, which was international cooperation. Some may point out the political rebels within Laos as a flaw of the post-communist transition. However, this is a problem of Laos itself regardless of the transition. The economic changes of Laos have already brought positive results in terms of interstate disputes. Therefore, to boost the effects of transition, Laos should consider taking further steps and bring about positive results among the disputes within the nation as well.

Once politically isolated and impoverished, Vietnam has grown into a much bigger economy as it went through Doi Moi, the economic reforms of 1986, building foundation for the further developments from a highly centralized economy to a socialist-oriented market economy. These post-communist transitions, synergized with the normalized relations with China in the 1990s have helped it to achieve enhanced security in the region. Although the number of MIDs has not shown a big difference, substantially lower hostility levels of disputes that occurred after the reform exemplifies how opening up positively affected the nation’s security compared to a decade before the reform.

Further research will be necessary in order to fully determine the relationship between economic liberalization and international security. Three countries are not enough to entirely forecast the future of another. Some may argue that the ongoing conflicts between China and Vietnam in recent years and growing tension in the Asian Pacific region regardless of economic prosperity, goes against the thesis of this paper.

However, at least with China, Laos, and Vietnam, the general outline leads us back to our liberal theory. All three countries – to different extents – demonstrated that after their post-communist transitions that resulted in more trade and international interdependence, the rate of conflict and level of hostility diminished in general. If further research results in a similar pattern among many more countries that have gone through post-communist transition, such results can be used to consider North Korea’s future prospects.

As one of a very few communist states left in the 21st century, North Korea has continued to remain firm in its economic and foreign policies throughout history. The international society has constantly urged the North Korean political system to undergo political reform. One of the means to encourage political change was to influence its traditional planned economic system. While its intimate neighboring countries, China and the Soviet Union chose to embrace the principles of the free market in the 1980s, North Korea maintained its status by using the concept of “juche” and claimed that North Korea was the only pure socialist state remaining after the socialist revolution. Unsurprisingly, this led to economic collapse of the nation in the early 1990s, but North Korea still did not consider economic reform as an option.[31]

However, the situation has changed in North Korea. With a new leader and its continuing economic deprivation, North Korea shows signs of reform; and witnessing the successful market entrance of its neighboring countries, North Korea’s procession into a free economy seems possible in the future. Will this march into post-communist transition mean more stability to the international society? According to the research of this paper, the forecasted answer is: to some extent, yes.

This finding leads to the policy implication that nations should aid the North Korean economy for the sake of maintaining and improving international security. The Kaesong Industrial District is an example where North Korea’s opening up, combined with South Korea’s funding, created a generally positive effect on the overall level of tension between the two Koreas. It still bears considerable problems, such as the dogmatic decision-making of North Korea; however, there is further potential for positive spillover effects with the Kaesong laborers gradually accepting South Korean rules and norms within the district. If North Korea embarks on a full-scale post-communist transition, we can expect the country’s military provocations to gradually decrease.

—

[1] Jones, Daniel M., Stuart A. Bremer, and David J. Singer, “Militarized Interstate Disputes, 1816-1992: Rationale, Coding Rules, and Empirical Patterns” Conflict Management and Peace Science, 15.2 (1996): 163-213.

[2] Damina Grammaticas, “Kim Jung-un’s First Public Speech,” News China BBC, 16 April 2012; accessed November 6, 2012.

[3] The Full Text of Kim Jung-un’s April 16 Speech; available from http://news.zum.com/articles/

2169954?c=01.

[4] Gale, Alastair. “North Korea Signals New Economic Push.” The Wall Street Journal. 27 Dec. 2013: <http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304753504579281770272632030>.

[5] “North Korea to Jointly Build Hi-tech Industrial Park with Foreign Firms.” Yonhap News Agency 24 Oct. 2013: <http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/northkorea/2013/10/23/45/0401000000AEN20131023006500325F.html>.

[6] “Chinese city seeks to run tours of economic zone in N. Korea.” Yonhap News Agency 6 June 2014: <http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/northkorea/2014/06/06/0401000000AEN20140606001700315.html>.

[7] Park, Yeon-mi. “The hopes of North Korea’s ‘Black Market Generation.’” The Washington Post Opinions 26 May 2014: <http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/yeon-mi-park-the-hopes-of-north-koreas-black-market-generation/2014/05/25/dcab911c-dc49-11e3-8009-71de85b9c527_story.html>.

[8] Barbieri, Katherine. “Economic Interdependence: A Path to Peace or a Source of Interstate Conflict?” Journal of Peace Research 2.1 (1996): 30.

[9] Barbieri, 30.

[10] Rosencrance, Richard. The Rise of the Trading State: Commerce and Conquest in the Modern World. (New York: Basic Books, 1986) 20.

[11] Edward Mansfield, Power, Trade, and War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994) 252-253.

[12] Cohen, Benjamin. The Question of Imperialism. (New York: Basic Books, 1973).

[13] Levy, Jack. The Causes of War, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989) 209-313.

[14] Jones, Daniel M., Stuart A. Bremer, and David J. Singer, “Militarized Interstate Disputes, 1816-1992: Rationale, Coding Rules, and Empirical Patterns” Conflict Management and Peace Science, 15.2 (1996): 163-213.

[15] He, Henry Yuhuai. Dictionary of the Political Though of the People’s Republic of China.. (New York: M E Sharpe Inc, 2000).

[16] Hammond, Andrew. “China is Increasingly Seen as the #1 Power, and that’s a Problem for China.” Forbes (5 Sept. 2013. <http://www.forbes.com/sites/realspin/2013/09/05/china-is-increasingly-seen-as-the-1-power-and-thats-a-problem-for-china/>.

[17] Phimphanthavong, H. “Economic reform and regional development of Laos.” Modern Economy 3 (2012): 179-186.

[18] Phimphanthavong, H. 179-186.

[19] Secret war. 2012. <http://library.thinkquest.org/trio/TR0110763/secretWar.html>.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Bertelsmann Transformation Index: Laos. 2003. <http://www.bti2003.bertelsmann-transformation-index.de/115.0.html?&L=1>.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] National Growth and Poverty Eradication Strategy. Lao People’s Democratic Republic 1 Jan. 2004. Web. 5 Jun. 2014. <http://www.la.undp.org/content/dam/laopdr/docs/Reports%20and%20publications/

Lao%20PDR%20-%20NGPES%20-%20Main%20Document.pdf>.

[26] Ninh, Le Khuong. “Investment of Rice Mills in Vietnam: the Role of Financial Markets Imperfections and Uncertainty.” Doctoral Dissertation, University of Groningen: (2003): Web. 11 Nov. 2012. <http://irs.ub.rug.nl/ppn/25039801x>.

[27] Che, Tuong Nhu, Tom Kompas and Neil Vousden. “Incentives and Static and Dynamic Gains from Market Reform: Rice Production in Vietnam.” The Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 45.4 (1999): 547-572.

[28] Arkadie, Brian and Raymond Mallon, Viet Nam—A Transition Tiger? (Canberra: Australian National University E Press). 68.

[29] Thayer, Carlyne. “Sino-Vietnamese Relations: the Interplay of Ideology and National Interest.” Asian Survey 34.6 (1994): 513-528.

[30] “China, Vietnam Find Love.” Asia Times 21 Jul. 2005: <http://www.atimes.com/atimes/

Southeast_Asia/GG21Ae01.html>.

[31] Stangarone, Troy and Nicholas Hamisevicz. “The Propects for Economic Reform in North Korea after Kim Jong-il and the China Factor.” International Journal of Korean Unification Studies 22.2 (2011): 175-197.

—

Written by: Hooyeon Kim, Dayoung Kim, Hansaim Kim, and Terri Kim

Written at: EWHA Womans University

Written for: Leif-Eric Easley

Date written: Autumn 2013

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- A Strategic Playground: What Are Russia’s Interests in Post-9/11 Central Asia?

- Mercenaries of Peace: The Role of Private Military Contractors in Conflict

- EU Foreign Policy in East Asia: EU-Japan Relations and the Rise of China

- Balancing Rivalry and Cooperation: Japan’s Response to the BRI in Southeast Asia

- Politics of Continuity and US Foreign Policy Failure in Central Asia

- Struggle and Success of Chinese Soft Power: The Case of China in South Asia